Weiblog

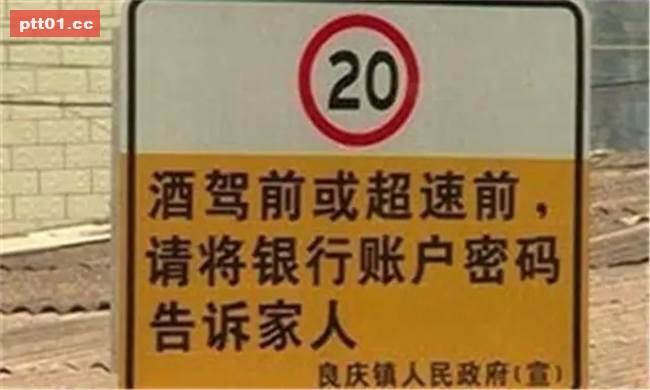

17 Funny Weibo Trending Pics

What’s on Weibo brings you an overview of 17 of the most ridiculous and funny classic pictures that have been making their rounds on China’s social media.

Newsletter

Tuning Into the Year of the Snake

China Digital

From “Public Megaphone” to “National Watercooler”: Casper Wichmann on Weibo’s Role in Digital China

With Weibo now 15 years old, we asked Sinologist Wichmann about its evolving role in shaping public opinion, its key moments, and whether it can remain a major platform for public discourse in China’s increasingly crowded digital landscape.

WHAT’S ON WEIBO CHAPTER: 15 YEARS OF WEIBO

Over the past fifteen years, the Chinese social media platform Weibo has been a popular and extensively studied subject in academic research, inspiring countless studies across various disciplines.

In the initial years after the founding of Weibo (read all about Weibo’s founding in this deep dive), Danish Sinologist and China correspondent Casper Wichmann, focused on Chinese digital platforms, dedicated his MA research to studying Sina Weibo as a new public sphere on the Chinese internet. Now that more than a decade has passed, it’s time to reflect on how Weibo has changed and why this matters.

Before Casper shares his observation, some key points from his thesis “Sina Weibo as New Public Sphere.” (For those interested, here is a link to the pdf):

➡️ Wichmann’s thesis (2012) analyzed how the Chinese microblogging platform Sina Weibo serves as a “public sphere” in China, providing a new space for citizens to share information and voice public opinion. Using frameworks like Jürgen Habermas’ theory of the public sphere, Johan Lagerkvist’s concept of ideotainment (blending Party propaganda with entertainment to build legitimacy), and Andrew Mertha’s fragmented authoritarianism (how political pluralization affects policy in China), the thesis explored how Sina Weibo functions as an independent media platform while working alongside traditional media. It examined how public opinion is formed on the platform and the significant influence of both traditional media and the Chinese Party-State.

➡️ The Party-State’s relationship with Sina Weibo is complex, balancing censorship with strategic allowances to monitor public opinion, address corruption, and maintain its legitimacy. Through case studies like the Wenzhou train crash and the Bo Xilai scandal, the thesis illustrated how Sina Weibo can amplify public opinion while also showcasing the Party-State’s ultimate control over discourse.

➡️ While Sina Weibo enables public engagement and amplifies citizens’ voices, Wichmann concluded that its role as a public sphere is limited or “incomplete” due to censorship by the Chinese Party-State, which also hape discourse, use the platform for propaganda, and influences its operations and moderation.

➡️ Wichmann predicted that Sina Weibo would increasingly become a “battlefield of public opinion,” where Chinese citizens and the Party-State would compete to control narratives and influence within this digital space.

With Weibo now 15 years old, we asked Wichmann about three things:

📌 Weibo’s evolving role in shaping public opinion: Has it become more or less effective, and has its social impact shifted? Which news stories highlight Weibo’s continued relevance or its changing influence?

📌 Changing government strategies on the Weibo platform: What pivotal moments stand out when Weibo emerged as a political tool?

📌 Weibo’s present & future in a crowded digital landscape: Can it still compete as a major platform for public discourse, or is it transitioning into a new role altogether?

Casper Wichmann

Sinologist, China Correspondent

Casper Wichmann is a Danish Sinologist with an MA degree in China studies from the University of Copenhagen. He wrote his MA thesis on Sina Weibo in 2012 and has especially had an interest in Chinese politics, tech and social media, among many other topics. Since 2023 he has been based in Beijing as the Asia & China correspondent for Danish news media, TV 2 Denmark.

Since 2023 he has been based in Beijing as the Asia & China correspondent for Danish news media, TV 2 Denmark.

📌Weibo’s Role in Shaping Public Opinion

“15 years is a very long time anywhere in the world, but particularly so in China. If you look at how the country has changed as a whole in those past years, it is inevitable that Weibo has also transformed.

One of the biggest things is of course censorship.

I worked on my thesis in the first half of 2012 and handed it in early September that year, and a lot was happening at the time when it comes to China’s online developments. I remember that I even wrote a disclaimer in the very beginning that the whole paper might be obsolete at the time of reading, because you had a sense of where the Chinese government were moving in terms of control.

As it turned out, the government started cracking down on the influential Weibo accounts (‘大Vs’ – big, verified accounts) not long after, and also introduced laws to stop the spread of rumors. This, in turn, also paved the way for WeChat’s rise to prominence. You now have a lot of different platforms and apps on the internet in China for debate and shaping public opinion.

“I still believe that you cannot overlook or understate Weibo’s role as the ‘watercooler’ of China.”

That said, I still believe that you cannot overlook or understate Weibo’s role as the ‘watercooler’ of China where everybody comes together to talk about current affairs.

In my thesis, I argued that Sina Weibo could be seen as a Habermasian public sphere—an incomplete one—where Chinese citizens can come together and, to a large extent, freely debate information and public opinion. Even though the censorship regime has become far more effective and sophisticated, coupled with increased self-censorship, I still think that conclusion holds true 15 years after Weibo’s launch.

It is an open platform—censorship and control aside—where everyone can read, participate in conversations, and share information with the click of a button. This is clearly demonstrated by the way What’s on Weibo has highlighted many important topics over the years that sparked national debates thanks to Weibo. Additionally, can any foreign brand aiming to succeed in the Chinese market afford to completely ignore Weibo? That would be unthinkable!

“Foreign brands can quickly find themselves caught in massive controversies because Weibo still acts as a public megaphone”

In terms of its effectiveness in shaping public opinion, I think that depends on how we look at it. For instance, foreign brands can quickly find themselves caught in massive controversies because Weibo still acts as a public megaphone. Just think of the scandals involving Dolce & Gabbana (2018), H&M (2021), or Dior (2022), to name a few.

Still from the promotional D&G video that was deemed racist in China, causing major controversy in 2018 (whatsonweibo).

There are also examples like the Tianjin explosion in 2015, which quickly became national news and sparked public debate, largely thanks to Weibo—despite the aforementioned censorship measures.

The enormous Tianjin explosions took place on August 12, injuring hundreds of people. Many people only learnt of the news through social media rather than traditional news outlets, which initially did not report the blasts.

Another example is the tragic death of Dr. Li Wenliang, the COVID-19 whistleblower, where netizens mourned his passing while venting their frustrations on Weibo.

Lastly, the spread of the “Voices of April” video—a compilation of real audio snippets capturing Shanghai residents’ struggles during the Covid crisis in April 2022—is another notable example of Chinese netizens overwhelming censorship by reaching critical mass. While this occurred across various platforms, Weibo played a key role due to its nature as a public space for discussion.

All in all, Weibo is still a very important and effective platform on the Internet in China for public discussions, debates, and shaping public opinion. However, it is also up against a censorship regime that has evolved and continues to evolve alongside it. That said, one should never underestimate the creativity of Chinese netizens.”

📌Government Strategies and Control on Weibo

“In the early years of Weibo, some Chinese politicians and overseers found use of Weibo as a political tool. A specific example I included in my thesis was the drama surrounding the political downfall of Bo Xilai, then party secretary of Chongqing and a rising princeling within the Party, and the Wang Lijun scandal.

There seemed to be considerable evidence that netizens on Weibo were allowed for a long time to criticize and slander Bo Xilai before censorship eventually stepped in. There is no doubt that this made it easier for the Party leadership to oust Bo Xilai following the high-profile corruption case.

“As a tool to gauge public opinion, Weibo also enables authorities to monitor potential issues and nip them in the bud before they escalate into major problems”

I also think that Weibo’s importance as a tool for the Chinese government to gauge public opinion and sentiment should not be underestimated. It enables authorities to monitor potential issues and nip them in the bud before they escalate into major problems. It also facilitates public scrutiny of lower-level officials and governance within the Chinese system (舆论监督 yúlùn jiāndū, “supervision by public opinion”, also see CMP).

Bo Xilai during his trial.

Another important point is that the government and Party seem to have learned that it is often safer to let people debate, complain, and vent online, as it can give them a sense of being heard and allow them to release frustrations without escalating into physical demonstrations. Of course, there are exceptions where such online discourse also leads to physical protests.

There is also the aspect of how long Chinese netizens can maintain focus on a specific topic. For example, the Tianjin explosion I mentioned earlier quickly became a national debate, but over time it shifted back to being a local issue as Weibo users moved on to other topics. I have no doubt that the Chinese government has increasingly learned to use this dynamic to their advantage. It would be fascinating to study which types of topics reach the top trending lists, how long they stay there, how they are censored, and what topics eventually replace them.”

📌Weibo’s Business and China’s Competitive Digital Landscape

“It really says a lot about Weibo that it has managed to remain significant in China’s digital landscape, even after the rise of other major platforms, including WeChat, and despite the strict regulations and major crackdowns on the platform.

For example, WeChat experienced a surge in active users after the 2012 crackdown, as many felt Weibo had become boring due to key opinion leaders being increasingly cautious of censorship.

“Platforms in China are competing to capture as much of Chinese netizens’ time and attention as possible.”

Nowadays, there is a growing number of newer and more exciting apps and platforms in China, all competing to capture as many hours, minutes, and seconds of Chinese netizens’ attention as possible. However, I believe Weibo’s unique usage and role in the digital ecosystem are hard to replicate.

To reiterate, the platform’s “national watercooler” aspect—where everyone can check in, get a sense of what the rest of the country is talking about, and join the conversation themselves—should not be underestimated.

That said, Weibo still needs to consistently provide a service and product that Chinese users feel offers them real value. If it can continue to do so, I don’t see Weibo becoming irrelevant anytime soon.”🔚

⭐ To read more about the evolution of Weibo, also read: “15 Years of Weibo: The Evolution of China’s Social Media Giant“

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music10 months ago

China Music10 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Insight11 months ago

China Insight11 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Digital8 months ago

China Digital8 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI