China Society

Hero or Zero? China’s Controversial Math Genius Jiang Ping

Humble prodigy or deceptive impostor? Jiang Ping has been fueling online discussions since her remarkable score in the Alibaba maths competition.

Published

9 months agoon

By

Ruixin Zhang

It’s rare for a math competition to become the focus of nationwide attention in China. But since 17-year-old vocational school student Jiang Ping made it to the top 12 among contestants from prestigious universities worldwide, her humble background and outstanding achievement sparked debates and triggered rumors.

About a month ago, nobody had ever heard of Jiang Ping (姜萍). But that all changed in June 2024, when the Alibaba Global Mathematics Competition announced its finalists. Organized by Alibaba’s DAMO Academy in collaboration with the China Association for Science and Technology and the Alibaba Foundation, this competition is open to math enthusiasts worldwide.

This year, among the finalists from top universities around the globe, the 17-year-old Jiang Ping from Jiangsu province stood out. Scoring 93 points and ranking 12th globally, she was not just the only girl in the top 30 but she was also not even a math major—Jiang studies fashion design at a local vocational school. Her remarkable score, combined with her humble background, thrust her into the center of an unexpected public debate.

‘Good Will Hunting’

When the Alibaba Math Competition finalist list was announced in June, Jiang Ping became an instant internet sensation. Her story seemed straight out of an inspiring movie: a poor family, a modest educational background, and exceptional intelligence.

According to her parents and teachers, Jiang Ping had excelled at math since middle school, far surpassing her peers. However, her talent was limited to mathematics, and her weakness in other subjects meant she could only attend a vocational school, and she enrolled at Lianshui Secondary Vocational School, a path often seen as a dead end in China’s competitive educational landscape.

Fate intervened when her math teacher, Wang Runqiu (王闰秋), a master’s graduate from Jiangsu University who never qualified for a PhD program, noticed her extraordinary talent during a monthly math exam. Wang, who also participated in Alibaba’s competition and ranked over 100th, provided Jiang with advanced math textbooks. He believed her potential should not go to waste.

Determined, Jiang Ping self-studied mathematics alongside her fashion design curriculum, even using an English-Chinese dictionary to understand partial differential equations textbooks in English. When Jiang heard that Alibaba’s competition had no educational requirements, she seized the opportunity, and her talent finally came to light.

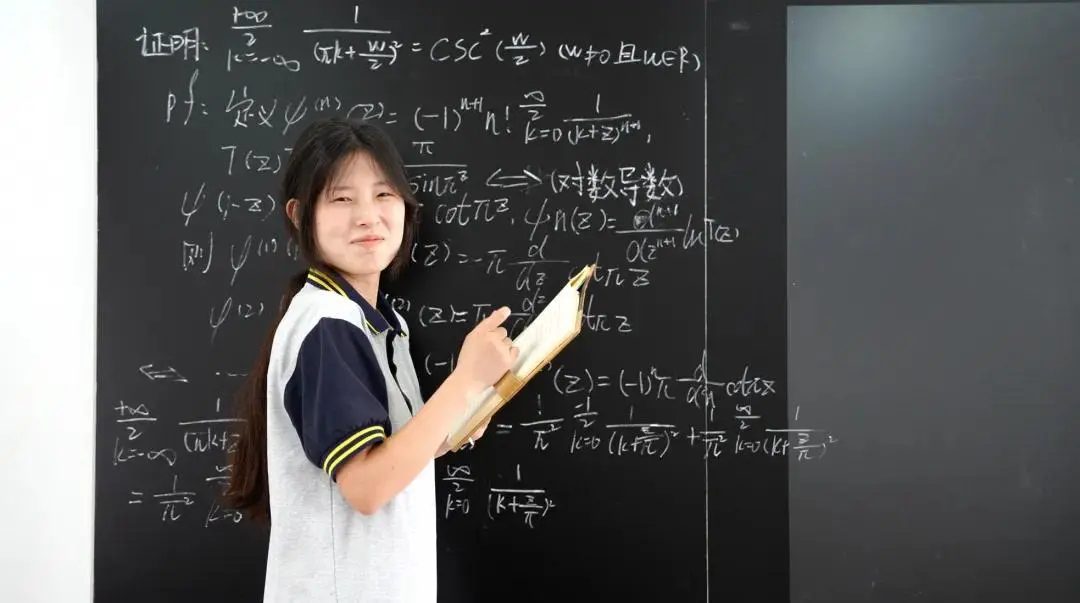

Jiang Ping, image via iFeng News.

The public initially seemed to love the story of a small-town Chinese girl experiencing a miraculous turning point in her life. Her 70-year-old father could hardly earn more than a few hundred yuan a month, and she often worked during holidays to help support her family.

According to Xinjing News, by March 2024, her family had applied for a subsistence allowance but had yet to receive it. After Jiang Ping’s story went viral, the allowance was immediately secured. Her village and school became new hotspots for influencers. Vloggers flocked to her home to film TikTok videos, and even tourists from other provinces visited Lianshui County just to take photos at Jiang’s school.

Wang Runqiu, Jiang Ping’s teacher

Everything seemed to be going well. Education blogger Luo Miao (@罗淼_吐槽用) posted that Jiang Ping and her teacher Wang Runqiu had achieved something more miraculous than the story portrayed in the American movie “Good Will Hunting,” which is also about a self-taught mathematical genius. However, the real world is not a movie. This celebration took a downturn in less than five days.

A Questionable Math Problem

Shortly after the finalists were announced and Jiang Ping’s name spread across social media, online discussions questioning her mathematical abilities began to emerge on forums like Zhihu. The focal point of these discussions was a scene from an official Alibaba video where Jiang Ping is seen holding scratch paper and solving a math problem on a blackboard.

On June 18, a WeChat post by renowned math competition coach Zhao Bin (赵斌) was trending on Weibo. Zhao, who had participated in the Alibaba competition three times and made it to the finals each time, asserted that Jiang Ping’s advancement to the finals was 99.99% likely fabricated. He raised doubts about Jiang Ping’s solution process on the blackboard, pointing out issues like “the domain of definition was incorrect” and “the differentiation symbol is written in the wrong place.” He concluded that Jiang was not familiar with these math questions and may have simply copied the answers from her scratch paper.

Zhao Bin further suggested that this might be orchestrated by Jiang Ping’s teacher Wang Runqiu, who probably wanted to hype up Jiang Ping’s image as an unrecognized genius and his own image as a mentor. Zhao also stated that if he was wrong, Jiang Ping truly was a math prodigy and that if she would make it to university, he would personally finance her tuition fees.

On June 19, 39 contestants from the Alibaba competition released a petition to the organizing committee. Besides the problems addressed by Zhao, they mentioned another point of contention: a teacher who had seen Jiang Ping’s exam paper commented that she exhibited “proficient use of LaTeX” while answering questions. LaTeX, a typesetting system for scientific documents, is highly sensitive to writing errors, which contradicts the frequent errors in Jiang Ping’s handwriting in the video.

This was also mentioned by Peking University professor Yuan Xinyi (袁新意) in a lengthy analysis on Zhihu, where he argued that as a vocational school student, Jiang Ping couldn’t possibly be proficient in using LaTeX. In their petition, the 39 contestants put forth specific demands, including the public release of Jiang Ping’s answer sheets for review by all finalists and a request for an independent third-party investigation.

Of course, there are those who choose to believe in Jiang Ping. Science fiction writer Bei Xing (@北星微博) made meticulous notes and explanations of Jiang Ping’s problem-solving process on the blackboard. He concluded that it was impossible to have such a clear approach if she had just copied someone else’s answers, as Zhao assumed. It was also understandable for a 17-year-old who had almost entirely self-taught herself to make some writing errors and formatting irregularities.

Up until this point, most discussions were still about academic integrity. But the fact that Alibaba and Damo Academy did not directly address these doubts only triggered more rumors. Many influencers with large followings, despite lacking a math background, also started to chime in with comments like “Jiang Ping doesn’t even recognize mathematical symbols,” leading to another surge of speculation and defamation directed at Jiang Ping.

Online Chaos

On June 23rd, the Weibo user ‘Oxford Kate Zhu Zhu’ (@牛津Kate朱朱), a mathematics PhD candidate at Oxford University, posted on Weibo that she had faced significant online abuse after expressing support for Jiang Ping. She said that she has sought legal assistance to deal with the online attacks. This post, which quickly went viral, showed how the controversy surrounding Jiang Ping has gone beyond mathematics or academic integrity.

By June 20th, Jiang Ping herself had already been doxxed. Someone posted her personal information online, including photos of her ID card. This practice is referred to as “opening the box” (开盒) on the Chinese internet. Netizens on platforms like Zhihu and Hupu began spreading rumors about Jiang Ping and her relationship with her mathematics teacher, with so-called “informants” even coming forward to allegedly confirm their “improper relationship.” Subsequently, a screenshot of Jiang Ping’s previous math exam score, showing she had scored only 83 points, was also leaked.

Professor of Criminal Law at Tsinghua University Lao Dongyan (@劳东燕2004) expressed concern about this situation, posting on Weibo to remind netizens that while people have the right to question Jiang Ping’s remarkable results, they should not throw around baseless accusations and push the debate in a direction that borders on defamation.

However, many people continue to see Jiang Ping’s amicable relationship with her teacher and her former 83-point exam score as justification to spread her private photos, transcripts, and even monthly exam papers on the Internet.

By now, the situation has become so messy that the Education Bureau of Lianshui County had to step in and set the record sraight on some trivial matters, such as the authenticity of Jiang’s monthly exam score and whether some teacher had bought her snacks or not.

Wang Hongqin vs Jiang Ping

Amidst the chaos, voices of reason remain: some netizens have expressed disappointment at Alibaba’s continued silence. They suggest that regardless of how Jiang Ping made it to the math competition finals, as an underage girl, she should not be thrust into the eye of the hurricane.

Meanwhile, another story has drawn parallels to Jiang’s situation. Recently, some netizens discovered that the son of the famous Chinese actress Wang Yan (王艳), Wang Hongqin (王泓钦), was admitted to Peking University as a “high-level athlete” based on his basketball talent. However, there are publicly available records indicating that his athletic achievements were not that impressive at all.

Wang Hongqin and Jiang Ping

This raised many discussions on Chinese social media. Netizens questioned why Jiang Ping, with her outstanding math achievements, wasn’t celebrated in the same way as Wang Hongqin. Others highlighted the disparity in opportunities for talented student from different backgrounds.

There were also questions about why Jiang Ping was receiving so much online hate, while Wang Hongqin did not. Under a Weibo post discussing Wang Yan’s son’s admission to Peking University, one comment explained public reasoning: “Wang Yan has access to high-level resources that are out of reach for ordinary people. In contrast, Jiang Ping is seen differently. When someone tries to break through societal layers [like that], they are dragged out and “paraded” through the streets.”

The discussions on the different public reactions to Wang Hongqin and Jiang Ping relate to a time of social insecurity when people face a competitive education system and a worsening job market. In this context, they are less likely to relate to “zero to hero” stories.

When someone with a low educational background achieves success, they are now often seen as cheaters rather than being celebrated. While people often feel powerless to challenge the privileges of the elite, the sudden rise of a vocational school student like Jiang Ping intensifies feelings of deprivation and being bypassed. Even though Jiang might have reached the finals through her own mathematical talent, there is still a lot of resentment towards the 17-year-old rural girl, who lacks background and connections. This misplaced anger is a reflection of deeper societal issues and inequalities.

Despite being at the center of the battlefield of public opinions, Jiang Ping has not made any statement yet. On June 22nd, she participated in Alibaba’s math competition finals, and perhaps now—as in every summer before—she is preparing to find a part-time job to support her family. The outcome of the finals will be announced in August, so Jiang Ping’s story will undoubtedly be continued.

Update November 2024:

The results of the 2024 Alibaba Mathematics Competition, originally set for August, are finally out. Neither Jiang Ping nor her teacher appears on the list. The competition committee released a statement confirming that Wang Runqiu had assisted Jiang Ping in the preliminaries, violating the “no collaboration with others” rule. It’s a disappointing outcome—not only because the competition allowed room for cheating, which Wang and Jiang exploited, but also because Jiang had become an inspirational role model for many math-loving girls from non-elite backgrounds. Now, she has fallen from that pedestal.

By Ruixin Zhang

edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Ruixin is a Leiden University graduate, specializing in China and Tibetan Studies. As a cultural researcher familiar with both sides of the 'firewall', she enjoys explaining the complexities of the Chinese internet to others.

China Insight

Squat or Sit? China’s Great Toilet Debate and the Problem of Footprints on the Seat

From squatting to standing on seats: the messy reality of sitting toilets in Beijing malls.

Published

3 weeks agoon

March 25, 2025

FROM THE WEIBO WATCH PREMIUM NEWSLETTER

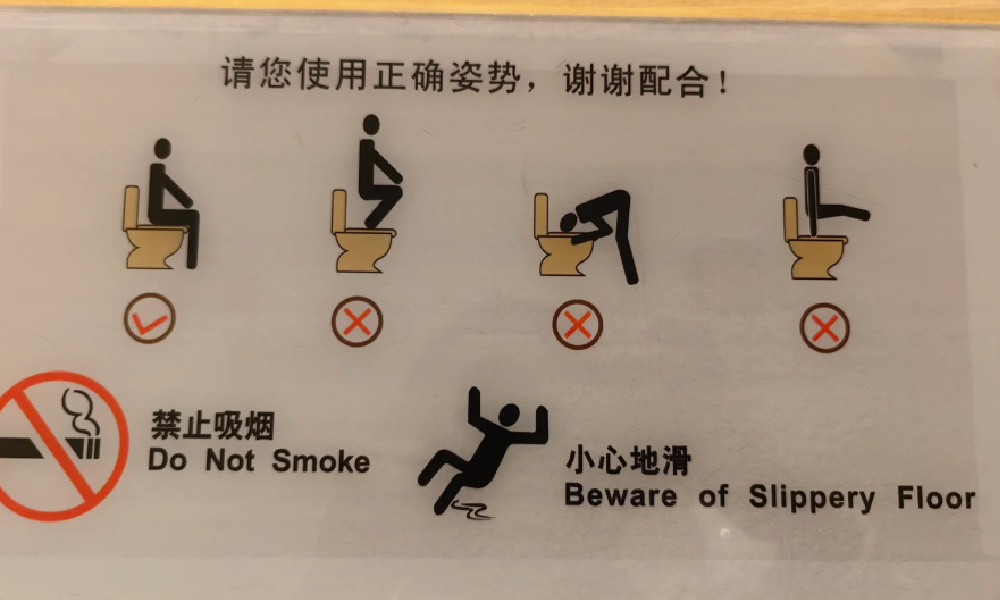

Shoe prints on top of the toilet seat are never a pretty sight. To prevent people from squatting over Western-style sitting toilets, there are some places that will place stickers above the toilet, reminding people that standing on the seat is strictly forbidden.

For years, this problem has sparked debate. Initially, these discussions would mostly take place outside of China, in places with a large number of Chinese tourists. In Switzerland, for example, the famous Rigi Railways caused controversy for introducing separate trains with special signs explaining to tourists, especially from China, how (not) to use the toilet.

Squat toilets are common across public areas in China, especially in rural regions, for a mix of historical, cultural, and practical reasons. There is also a long-held belief — backed by studies (like here or here) — that the squatting position is healthier for bowel movements (for more about the history of squat toilets in China, see Sixth Tone’s insightful article here).

Public squatting toilets in Beijing, images via Xiaohongshu.

Without access to the ground-level squat toilets they are used to — and feel more comfortable with — some people will climb on top of sitting toilets to use them in the way they’re accustomed to, seeing squatting as the more natural and hygienic method.

Not only does this make the toilet seat all messy and muddy, it is also quite a dangerous stunt to pull, can break the toilet, and lead to pee and poo going into all kinds of unintended directions. Quite shitty.

Squatting on toilets makes the seat dirty and can even break the toilet.

Along with the rapid modernization of Chinese public facilities and the country’s “Toilet Revolution” over the past decade, sitting toilets have become more common in urban areas, and thus the sitting-toilet-used-as-squat-toilet problem is increasingly becoming topic of public debate within China.

The Toilet Committee and Preference for Sitting Toilets

Is China slowly shifting to sitting toilets? Especially in modern malls in cities like Beijing, or even at airports, you see an increasing number of Western-style sitting toilets (坐厕) rather than squatting toilets (蹲厕).

This shift is due to several factors:

🚽📌 First, one major reason for the rise in sitting toilets in Chinese public places is to accommodate (foreign) tourists.

In 2015, China Daily reported that one of the most common complaints among international visitors was the poor condition of public toilets — a serious issue considering tourists are estimated to use public restrooms over 27 billion times per year.

That same year, China’s so-called “Toilet Revolution” (厕所革命) began gaining momentum. While not a centralized campaign, it marked a nationwide push to upgrade toilets across the country and improve sanitation systems to make them cleaner, safer, and more modern.

This movement was largely led by the tourism sector, with the needs of both domestic and international travelers in mind. These efforts, and the buzzword “Toilet Revolution,” especially gained attention when Xi Jinping publicly endorsed the campaign and connected it to promoting civilized tourism.

In that sense, China’s toilet revolution is also a “tourism toilet revolution” (旅游厕所革命), part of improving not just hygiene, but the national image presented to the world (Cheng et al. 2018; Li 2015).

🚽📌 Second, the growing number of sitting toilets in malls and other (semi)public spaces in Beijing relates to the idea that Western-style toilets are more sanitary.

Although various studies comparing the benefits of squatting and sitting toilets show mixed outcomes, sitting toilets — especially in shared restrooms — are generally considered more hygienic as they release fewer airborne germs after flushing and reduce the risk of infection (Ali 2022).

There are additional reasons why sitting toilets are favored in new toilet designs. According to Liang Ji (梁骥), vice-secretary of the Toilet Committee of the China Urban Environmental Sanitation Association (中国城市环境卫生协会厕所专业委员会), sitting toilets are also increasingly being introduced in public spaces due to practical concerns.

🚽📌 Squatting is not always easy, and can pose a safety risk, particularly for the elderly, pregnant women, and people with disabilities.

🚽📌 Then there are economic reasons: building squat toilets in malls (or elsewhere) requires a deeper floor design due to the sunken space needed below the fixture, which increases both construction time and cost.

🚽📌 Liang also points to an aesthetic factor: sitting toilets simply look more “high-end” and are easier to clean, which is why many consumer-oriented spaces prefer to install Western-style toilets.

So although there are plenty of reasons why sitting toilets are becoming a norm in newly built public spaces and trendy malls, they also lead to footprints on toilet seats — and all the problems that come with it.

The Catch 22 of Sitting vs Squad Toilets

This week, the issue became a trending topic on Weibo after Beijing News published an investigative report on it. The report suggested that most shopping malls in Beijing now have restrooms with sitting toilets, which should, in theory, be cleaner than the squat toilets of the past — but in reality, they’re often dirtier because people stand on them. This issue is more common in women’s restrooms, as men’s restrooms typically include urinals.

In researching the issue, a reporter visited several Beijing malls. In one women’s restroom, the reporter observed 23 people entering within five minutes. Although the restroom had only three squat toilets versus seven sitting ones, around 70% of the users opted for the squat toilets.

Upon inspection, most of the seven sitting toilets were dirty — despite being equipped with disposable seat covers — showing clear signs of urine stains and footprints. They found that sitting toilets being used as squat toilets is extremely common.

It’s a bit of a Catch-22. People generally prefer clean toilets, and there’s also a widespread preference for squat toilets. This leads to sitting toilets being used as squat toilets, which makes them dirty — reinforcing the preference for squat toilets, since the sitting toilets, though meant to be cleaner, end up dirtier.

In interviews with 20 women, nearly 80% said they either hover in a squat or directly squat on the toilet seat. One woman said, “I won’t sit unless I absolutely have to.” While some of those quoted in the article said that sitting toilets are more comfortable, especially for elderly people, they are still not preferred when the seats are not clean.

In the Beijing News article, the Toilet Committee’s Liang Ji suggested that while a balanced ratio of squat and sitting toilets is necessary, a gradual shift toward sitting toilets is likely the future for public restrooms in China.

How NOT to use the sitting toilet. Sign photographed by Xiaohongshu user @FREAK.00.com.

Liang also highlighted the importance of correct toilet use and the need to consider public habits in toilet design.

In Squatting We Trust

On Chinese social media, however, the majority of commenters support squatting toilets. One popular comment said:

💬 “Please make all public toilets squat toilets, with just one sitting toilet reserved for people with disabilities.”

Squatting toilets in a public toilet in a Beijing hutong area, image by Xiaohongshu user @00后饭桶.

The preference for squatting, however, doesn’t always come down to bowel movements or tradition. Many cite a lack of trust in how others use public toilets:

💬 “When it comes to things for public use, it’s best to reduce touching them directly. Honestly, I don’t trust other people…”

💬 “Squatting is the most hygienic. At least I don’t have to worry about touching something others touched with their skin.”

💬 “I hate it when all the toilets in the women’s restroom at the mall are sitting toilets. I’m almost mastering the art of doing the martial-arts squat (蹲马步).”

Others view the gradual shift toward sitting toilets as a result of Westernization:

💬 “Sitting toilets are a product of widespread ‘Westernization’ back in the day — the further south you go, the worse it gets.”

But some come to the defense of sitting toilets:

💬 “Are there really still people who think squat toilets are cleaner? The chances of stepping in poop with squat toilets are way higher than with sitting ones. Sitting toilet seats can be wiped with disinfectant or covered with paper. Some people only care about keeping themselves ‘clean’ without thinking about whether the next person might end up stepping in their mess.”

💬 One reply bluntly said: “I don’t use sitting toilets. If that’s all there is, I’ll just squat on top of it. Not even gonna bother wiping it.”

It’s clear this debate is far from over, and the issue of people standing on toilet seats isn’t going away anytime soon. As China’s toilet revolution continues, various Toilet Committees across the country may need to rethink their strategies — especially if they continue leaning toward installing more sitting toilets in public spaces.

As always, Taobao has a solution. For just 50 RMB (~$6.70), you can order an anti-slip sitting-to-squatting toilet aid through the popular e-commerce platform.

The Taobao solution.

For Chinese malls, offering these might be cheaper than dealing with broken toilets and the never-ending battle against footprints on toilet seats…

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

References:

Ali, Wajid, Dong-zi An, Ya-fei Yang, Bei-bei Cui, Jia-xin Ma, Hao Zhu, Ming Li, Xiao-Jun Ai, and Cheng Yan. 2022. “Comparing Bioaerosol Emission after Flushing in Squat and Bidet Toilets: Quantitative Microbial Risk Assessment for Defecation and Hand Washing Postures.” Building and Environment 221: 109284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109284.

Bhattacharya, Sudip, Vijay Kumar Chattu, and Amarjeet Singh. 2019. “Health Promotion and Prevention of Bowel Disorders Through Toilet Designs: A Myth or Reality?” Journal of Education and Health Promotion 8 (40). https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_198_18.

Cao, Jingrui 曹晶瑞, and Tian Jiexiong 田杰雄. 2025. “城市微调查|商场女卫生间,坐厕为何频频变“蹲坑”? [In Shopping Mall Women’s Restrooms, Why Do Sitting Toilets Frequently Turn into ‘Squat Toilets’?]” Beijing News, March 20. https://weibo.com/ttarticle/p/show?id=2309405146044773302810. Accessed March 19, 2025.

Cheng, Shikun, Zifu Li, Sayed Mohammad Nazim Uddin, Heinz-Peter Mang, Xiaoqin Zhou, Jian Zhang, Lei Zheng, and Lingling Zhang. 2018. “Toilet Revolution in China.” Journal of Environmental Management 216: 347–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.09.043.

Dai, Wangyun. 2018. “Seats, Squats, and Leaves: A Brief History of Chinese Toilets.” Sixth Tone, January 13. https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1001550. Accessed March 22, 2025.

Li, Jinzao. 2015. “Toilet Revolution for Tourism Evolution.” China Daily, April 7. https://europe.chinadaily.com.cn/opinion/2015-04/07/content_20012249_2.htm. Accessed March 22, 2025.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Food & Drinks

China Trending Week 11: The Yang Braised Chicken Scandal, Haidilao Pee Incident, Taiwan Tensions

What’s been trending on Weibo and beyond? I doomscrolled Chinese social media so you don’t have to.

Published

1 month agoon

March 13, 2025

Here’s the latest roundup of the three top trends and most noteworthy discussions on Chinese social media this week.

🍚🤢Yang’s Braised Chicken Rice Scandal

The popular Chinese franchise Yang’s Braised Chicken Rice (杨铭宇黄焖鸡米饭) is at the center of attention this week—for all the wrong reasons. The company, which opened its first restaurant in 2011 and has since franchised more than 2500 locations across China, was exposed by Beijing News for reusing expired ingredients and reselling leftover food in at least three of its restaurants in Zhengzhou and Shangqiu (Henan). Cooks were smoking in the kitchen and even going as far as dyeing spoiled, darkened beef with food coloring to make it appear fresh.

The issue has sparked widespread concern on Chinese social media—not only because Yang’s Braised Chicken Rice is a well-known restaurant chain, but also because food safety and kitchen hygiene remain ongoing concerns in China. The timing of this news is particularly significant, as it was published in the lead-up to March 15—China’s National Consumer Rights Day, an annual event that highlights consumer protection issues.

China’s State Council Food Safety Commission Office has now ordered authorities in Henan and Shandong, where Yang’s Braised Chicken is headquartered, to thoroughly investigate the case. The affected stores will reportedly be closed permanently, but the impact extends far beyond these locations—most netizens discussing the scandal have made it clear they won’t be ordering from Yang’s Braised Chicken Rice anytime soon.

Can the company win back consumer trust? Even though general management has been apologizing and pledged to personally oversee kitchen standards, this is not the first time the company is in hot water. In 2024, a customer in Chengdu allegedly ordered Yang’s Braised Chicken Rice via takeout and discovered a fully cooked dead rat in their meal (picture here not for the faint of heart).

🇹🇼⚔️Beijing Angrily Responds to Lai Ching-te’s Speech: “Pushing Taiwan Towards the Danger of War”

While tough language on Taiwan was already trending last week during China’s Two Sessions, another wave of discussions on Taiwan has emerged this week. This follows a high-level national security meeting held on Thursday by Taiwanese President Lai Ching-te (赖清德), after which he addressed the media and proposed more aggressive strategies to counter Beijing’s so-called ‘united front’ efforts within Taiwan.

On Friday, Beijing responded with stern remarks. Chen Binhua (陈斌华), spokesperson for the Taiwan Affairs Office of the State Council, called Lai Ching-te a “destroyer of cross-strait peace” (“两岸和平破坏者”) and a “creator of crises in the Taiwan Strait” (“台海危机制造者”) who is “pushing Taiwan towards the dangerous situation of war” (“把台湾推向兵凶战危险境”).

Chen also reiterated Beijing’s stance that reunification with Taiwan is inevitable. This message was further amplified on Chinese social media platforms such as Weibo and Douyin through the hashtag “Inevitable Reunification with the Motherland” (#祖国必然统一#).

🔥🚽Haidilao’s “Pissgate”

Last week, on March 6, a peculiar news item went viral on Chinese social media, and I tweeted out the viral video here. The footage shows a young man standing on a table in a private dining room at a Haidilao restaurant, seemingly urinating into the hotpot. The incident was later confirmed to have taken place at the popular chain’s Bund location in Shanghai on the night of February 24.

Just when you thought the world couldn’t get any crazier… someone stands up and pisses in the Haidilao hotpot. Blasphemy! Hotpot treason!

Anyway, Haidilao reported the guy to the police, and I’m pretty sure he won’t be welcome back anytime soon. pic.twitter.com/3ytLhGdYjX

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) March 6, 2025

Honestly, the video seemed staged (the “pee” looked more like water), but understandably, Haidilao was very pissed about the negative impact on its reputation. In case you’re not familiar: Haidilao is one of China’s most popular hotpot chains, known for its excellent service and food quality (read here).

The company immediately launched an investigation into the video’s origins and reported the two men—the one urinating and the one filming—to the police.

This week, the incident gained even more traction (even the BBC covered it) after it was revealed that Haidilao had reimbursed 4,109 customers who dined at the restaurant between February 24, when the incident occurred, and March 8, when all tableware was discarded and the entire restaurant was disinfected.

Not only did Haidilao reimburse customers, but they also compensated them tenfold.

This compensation strategy sparked all kinds of discussions on Chinese social media. While many agreed with Haidilao’s solution to prevent a marketing crisis, some customers and netizens raised ethical questions, such as:

💰If you paid for your meal with coupons and only spent a couple of cents in cash, is it fair that some customers only received 9 RMB ($1.25) in compensation?

💰If you paid for an entire group of friends, meaning you originally spent around $140 on a meal but now received $1,400 in reimbursement, should you split the compensation with your friends?

💰How should cases be handled where a third party made the reservation and ends up claiming part of the compensation?

By now, the incident has become about much more than just pissing in soup.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

China Reacts: 3 Trending Hashtags Shaping the Tariff War Narrative

No Quiet Qingming: From High-Tech Tomb-Sweeping to IShowSpeed & the Seven China Streams

From Trade Crisis to Patriotic Push: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Tariffs

China Trending Week 14: Gucci Fake Lipstick, Xiaomi SU7 Crash, Yoon’s Impeachment

Strange Encounter During IShowSpeed’s Chengdu Livestream

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Beyond the Box Office: What’s Behind Ne Zha 2’s Success?

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

15 Years of Weibo: The Evolution of China’s Social Media Giant

Tuning Into the Year of the Snake

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

TikTok Refugees, Xiaohongshu, and the Letters from Li Hua

The ‘China-chic Girl’ Image and the Realities of China’s Competitive Food Delivery Market

US-Russia Rapprochement and “Saint Zelensky”: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Shake-Up

“Black Myth: Wukong”: From Gaming Screens to the CMG Spring Festival Gala?

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight11 months ago

China Insight11 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

-

China Arts & Entertainment11 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment11 months agoSinging Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

crabfood

July 5, 2024 at 9:33 pm

spicy story. *thumbs up*