China Celebs

These Are China’s Youngest Billionaires

What’s on Weibo explores who the richest kids of mainland China are: a top 10 of China’s youngest billionaires, according to the Forbes List of the World’s Billionaires.

Published

9 years agoon

After inheriting a fortune from her father, the 19-year-old Alexandra Andresen has been named the youngest billionaire on the globe by the Forbes World’s Billionaire List. Forbes has got Weibo talking about money.

The teenage girl Alexandra Andresen from Norway is worth an estimated 1.2 billion US$ according to the Forbes billionaires list. The young rich woman became trending on China’s social media site Sina Weibo under the title of ’19-year-old girl becomes world’s youngest multi-millioniare’ (19岁少女成世界最年轻亿万富翁).

In light of this news, What’s on Weibo explores who the richest ‘kids’ of mainland China are: a top 10 of China’s youngest billionaires, according to Forbes’ World’s Billionaires.

No. 1 – Wang Han (王瀚, 28 years old): 1.3 billion US$

At just 28 years, Wang Han became one of the world’s youngest billionaires – he is number 7 in the international top 10. Wang became a billionaire after inheriting shares in regional airline Juneyao Air (吉祥航空有限公司) from his late father Wang Junyao (王均瑶), who was the founder. According to Forbes,

Wang Han owns 27% of the airline and 14% of department store Wuxi Commercial Mansion Grand Orient (无锡商业大厦大东方股份有限公司). The Juneyao Group also has businesses in the education and food sector. They are also active on social media; Juneyao also has a rather large fanbase on its Weibo account.

No. 2 – Wang Yue (王悦, 32 years old): 1.1 billion US$

Wang Yue is a newcomer to the list of the world’s youngest billionaires, according to Forbes 2016. He is called China’s “web game billionaire”. Wang earned a fortune being an online and mobile game entrepreneur. He is the CEO of Shanghai Kingnet Technology (上海恺英网络科技有限公司), better known as Kingnet (恺英网络).

No. 3 – Cheng Wei (程维, 33 years old): 1 billion US$

Cheng Wei (程维, 1983) is CEO of China’s Uber rival Didi Kuaidi (滴滴快滴), a transportation company which was formed in early 2015 as a merge of Cheng’s company Didi Dache and Alibaba’s Kuaidi Dache. Previous to starting his own company, Cheng worked for Alibaba for 8 years and became vice president for Alibaba’s online payment service Alipay. Cheng has a verified Weibo account, but he has not posted much since his rise to fame.

No. 4 – Yang Huiyan (杨惠妍, 34 years old): 4.9 billion US$

Born in 1981, Yang Huiyan from Guangdong’s Foshan is one of the world’s richest women. She became the largest shareholder of real estate developer Country Garden Holdings (碧桂园集团) after her father transferred his holdings to her when she was just 25 years old (also see the featured image). According to its official website, Country Gardens is “a company constantly fighting for the development of a harmonious society.”

No. 5 – Frank Wang Tao (汪滔, 35 years old): 3.6 billion US$

Wang Tao, also known in English as Frank Tao or Frank Wang, is the founder and CEO of Shenzhen-based DJI, the world’s largest supplier of civilian drones. Forbes describes him as “the world’s first drone billionaire”. Headquartered in China’s “Silicon Valley” Shenzhen, DJI started as a single small office in 2006, and has now turned into to a global workforce of over 3,000. Their offices can be found in the United States, Germany, the Netherlands, Japan, Beijing and Hong Kong (dji.com).

No. 6 – Zhang Bangxin (张邦鑫, 35 years old): 1.01 billion US$

Who ever thought after school tutoring could make you rich? Zhang Bangxin (1980) is the cofounder, chairman and CEO of the Beijing-based educational tutoring firm TAL Education Group (世纪好未来教育科技有限公司). The company has been around since 2003, and it provides after-school tutoring for pupils from kindergarten to 12th grade at over 500 locations throughout China. Zhang is also an official Weibo microblogger, but, like his fellow billionaires in this list, he might be too busy making money to actually post on social media.

No. 7 – Cai Xiaoru (蔡小如, 36 years): 1.2 billion US$

Cai Xiaoru is chairman of Tatwah Smartech (达华智能), a company that is specialized in the research, development, manufacture and distribution of radio frequency identification (RFID). The company produces, amongst others, non-contact IC cards and electronic labels. Cai became a billionaire in mid-2015, following the fast-growing stock price of Tatwah Smartech.

No. 8 – Li Weiwei (李卫伟 aka 李逸飞, 37 years): 1.3 billion US$

For Li Weiwei, it is all work and all play. The young entrepreneur, who was born in Chengdu city, is the vice chairman of online game company Wuhu Shunrong Sanqi Interactive Entertainment Network Technology (芜湖顺荣三七互娱网络科技股份有限公司). The company is better known under the name of 37wan, a platform that offers high-quality game products. Li Weiwei is also known as Li Yifei (李逸飞).

No. 9 – Zhou Yahui (周亚辉, 39 years): 2 billion US$

Another billionaire who got rich through the gaming industry is Zhou Yahui (1977) – the CEO of Beijing Kunlun Tech (北京昆仑万維科技股份有限公司). Kunlun Tech is one of China’s biggest web game developers and operators. In January of 2016, NY Times reported that the company paid $93 million for a 60% stake of Grindr, the largest social networking app for gay men in the world. With over 2 million daily users in 196 countries, the app has proven to be a good investment for Zhou.

No. 10 – Wu Gang (吴刚, 39 years old): 1.3 billion US$

Wu Gang is co-founder and CEO of money management company Beijing Tongchuang Jiuding Investment Management (北京同创九鼎投资管理股份有限公司), better known as JDcapital (九鼎投资), “a leading investment firm with deep roots in equity investment and management”, as it describes itself.

On Weibo, some netizens have asked Norwegian billionaire Alexandra Andresen to come and visit China. With so many other billionaires, the young heiress will certainly have no reason to feel lonely at the top in China.

– By Manya Koetse

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

Sources:

*163 (2015): http://news.163.com/15/1104/14/B7J6UOEO00014AED.html

*Jiangsu.China.com (2015): http://jiangsu.china.com.cn/html/jsnews/gnxw/2758273_2.html

*Forbes.com (various pages, see in-text links) and the China Rich List sorted by age.

Images:

Featured: Yang Huiyan (http://blog.sina.com.cn)

– http://www.ittime.com.cn/news/news_10433.shtml

– http://www.eeyy.com/jinjing/2014/

– http://uk.china-info24.com/british/tic/ht/20150729/200775.html

– http://baike.baidu.com/view/880927.htm

– http://startupbeat.hkej.com/?author=12

– http://www.cyzone.cn/a/20131114/247015.html

– http://money.163.com/15/1216/07/BAULIVAD00252G50.html

– http://www.laonanren.com/news/2015-11/104275.htm

– http://www.forbes.com/profile/zhou-yahui-1/

– http://www.gsm.pku.edu.cn

©2016 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Arts & Entertainment

Controversial Wanghong Livestreamers Are Becoming a Weibo Staple in China

‘Wanghong’ was a mark of online fame; now, it’s increasingly tied to controversy and scandal.

Published

4 months agoon

October 27, 2024

As livestreaming continues to gain popularity in China, so do the controversies surrounding the industry. Negative headlines involving high-profile livestreamers, as well as aspiring influencers hoping to make it big, frequently dominate Weibo’s trending topics.

These headlines usually revolve around China’s so-called wǎnghóng (网红) influencers. Wanghong is a shortened form of the phrase “internet celebrity” (wǎngluò hóngrén 网络红人). The term doesn’t just refer to internet personalities but also captures the viral nature of their influence—describing content or trends that gain rapid online attention and spread widely across social media.

Recently, an incident sparked debate over China’s wanghong livestreamers, focusing on Xiaohuxing (@小虎行), a streamer with around 60,000 followers on Douyin, who primarily posts evaluations of civil aviation services in China.

Xiaohuxing (@小虎行)

On October 15, 2024, at Shenzhen Bao’an International Airport, Xiaohuxing confronted a volunteer at the automated check-in counter, insisting she remove her mask while livestreaming the entire encounter. He was heard demanding, “What gives you the right to wear a mask? What gives you the right not to take it off?” and even attempted to forcibly remove her mask, challenging her to call the police.

During the livestream, the livestreamer confronted the woman on the right for wearing a facemask.

He also argued with a male traveler who tried to intervene. In the end, the airport’s security officers detained him. Shortly after the incident, a video of the livestream went viral on Weibo under various hashtags (e.g. #网红小虎行机场强迫志愿者摘口罩#) and attracted millions of views. The following day, Xiaohuxing’s Douyin account was banned, and all his videos were removed. The Shenzhen Public Security Bureau later announced that the account’s owner, identified as Wang, had been placed in administrative detention.

On October 13, just days before, another livestreaming controversy erupted at Guangzhou Baiyun International Airport. Malatang (@麻辣烫), a popular Douyin streamer with over a million followers, secretly filmed a young couple kissing and mocked them, continuing to film while passing through security—an area where filming is prohibited.

Her livestream quickly went viral, sparking discussions about unauthorized filming and misconduct among Chinese wanghong. In response, Malatang’s agent posted an apology video. However, the affected couple hired a lawyer and reported the incident to the police (#被百万粉丝网红偷拍当事人发声#). On October 17, Malatang’s Douyin account was banned, and her videos were removed.

Livestreamer Malatang making fun of the couple in the back at the airport.

In both cases, netizens uncovered additional examples of inappropriate behavior by Xiaohuxing and Malatang in past broadcasts. For example, Xiaohuxing was reportedly aggressive towards a flight attendant, demanding she kneel to serve him, while Malatang was criticized for scolding a delivery person who declined to interact with her on camera.

Comments on Weibo included, “They’ll do anything for traffic. Wanghong are getting a bad reputation because of people like this.” Another added, “It seems as if ‘wanghong’ has become a negative term now.”

Rising Scrutiny in China’s Wanghong Economy

Xiaohuxing and Malatang are far from isolated cases. Recently, many other wanghong livestreamers have also been caught up in negative news.

One such figure is Dong Yuhui (董宇辉), a former English teacher at New Oriental (新东方) who transitioned to livestreaming for East Buy (东方甄选), where he mixed education with e-commerce (read here). Dong gained significant popularity and boosted East Buy’s brand before leaving to start his own company. Recently, however, Dong faced backlash for inaccurate statements about Marie Curie during an October 9 livestream. He incorrectly claimed that Curie discovered uranium, invented the X-ray machine, and won the Nobel Prize in Literature, among other things.

Considering his public image as a knowledgeable “teacher” livestreamer, this incident sparked skepticism among viewers about his actual expertise. A related hashtag (#董宇辉称居里夫人获得诺贝尔文学奖#) garnered over 81 million views on Weibo. In addition to this criticism, Dong is also being questioned about potential false advertising, which is a major challenge for all livestreamers selling products during their streams.

Dong Yuhui (董宇辉) during one of his livestreams.

Another popular livestreamer, Dongbei Yujie (@东北雨姐), is currently also facing criticism over product quality and false advertising claims. Originally from Northeast China, Dongbei Yujie shares content focused on rural life in the region. Recently, her Douyin account, which boasts an impressive 22 million followers, was muted due to concerns over the quality of products she promoted, such as sweet potato noodles (which reportedly contained no sweet potato). Despite issuing public apologies—which have garnered over 160 million views under the hashtag “Dongbei Yujie Apologizes” (#东北雨姐道歉#)—the controversy has impacted her account and led to a penalty of 1.65 million yuan (approximately 231,900 USD).

From Dongbei Yujie’s apology video

Former top Douyin livestreamer Fengkuang Xiaoyangge (@疯狂小杨哥) is also facing a career downturn. Leading up to the 2024 Mid-Autumn Festival, he promoted Hong Kong Meicheng mooncakes in his livestreams, branding them as a high-end Hong Kong product. However, it was soon revealed that these mooncakes had no retail presence in Hong Kong and were primarily produced in Guangzhou and Foshan, sparking accusations of deceptive marketing. Due to this incident and previous cases of misleading advertising, his company came under investigation and was penalized. In just a few weeks, Fengkuang Xiaoyangge lost over 8.5 million followers (#小杨哥掉粉超850万#).

Fengkuang Xiaoyangge (@疯狂小杨哥) and the mooncake controversy.

It’s not only ecommerce livestreamers who are getting caught up in scandal. Recently, the influencer “Xiaoxiao Nuli Shenghuo” (@小小努力生活) and her mother were arrested for fabricating a tragic story – including abandonment, adoption, and hardships – to gain sympathy from over one million followers and earn money through donations and sales. They, and two others who helped them manage their account, were sentenced to ten days in prison for ‘false advertising.’

Wanghong Fame: Opportunity and Risk

China’s so-called ‘wanghong economy’ has surged in recent years, with countless content creators emerging across platforms like Douyin, Kuaishou, and Taobao Live. These platforms have transformed interactions between content creators and viewers and changed how products are marketed and sold.

For many aspiring influencers, becoming a livestreamer is the first step to building a presence in the streaming world. It serves as a gateway to attracting traffic and potentially monetizing their online influence.

However, before achieving widespread fame, some livestreamers resort to using outrageous or even offensive content to capture attention, even if it leads to criticism. For example, before his account was banned, Xiaohuxing set his comment section to allow only followers to comment, gaining 3,000 new followers after his controversial livestream at Shenzhen Airport went viral. Many speculated that some followers joined just to leave critical comments, but it nonetheless grew his following.

As livestreamers gain significant fame, they must exercise greater caution, as they often hold substantial influence over their audiences, making accuracy essential. Mistakes, whether intentional or not, can quickly erode trust, as seen in the example of the super popular Dong Yuhui, who faced backlash after his inaccurate comment about Marie Curie sparked public criticism.

China’s top makeup livestreamer, Li Jiaqi (李佳琦), experienced a similar reputational crisis in September last year. Responding dismissively to a viewer who commented on the high price of an eyebrow pencil, Li replied, “Have you received a raise after all these years? Have you worked hard enough?” Commentators pointed out that the pencil’s cost per gram was double that of gold at the time. Accused of “forgetting his roots” as a former humble salesman, Li lost one million Weibo followers in a day (read more here).

This meme shows that many viewers did not feel moved by Li’s apologetic tears after the eyepencil incident.

Despite the challenges and risks, becoming a wanghong remains an attractive career path for many. A mid-2023 Weibo survey on “Contemporary Employment Trends” showed that 61.6% of nearly 10,000 recent graduates were open to emerging professions like livestreaming, while 38.4% preferred more traditional career paths.

Taming the Wanghong Economy

In response to the increasing number of controversies and scandals brought by some wanghong livestreamers, Chinese authorities are implementing stricter regulations to monitor the livestreaming industry.

In 2021, China’s Propaganda Department and other authorities began emphasizing the societal influence of online influencers as role models. That year, the China Association of Performing Arts introduced the “Management Measures for the Warning and Return of Online Hosts” (网络主播警示与复出管理办法), which makes it challenging, if not impossible, for “canceled” celebrities to stage a comeback as livestreamers (read more).

The Regulation on the Implementation of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Consumer Rights and Interests (中华人民共和国消费者权益保护法实施条例), effective July 1, 2024, imposes stricter rules on livestream sales. It requires livestreams to disclose both the promoter and the product owner and mandates platforms to protect consumer rights. In cases of illegal activity, the platform, livestreaming room, and host are all held accountable. Violations may result in warnings, confiscation of illegal earnings, fines, business suspensions, or even the revocation of business licenses.

These regulations have created a more controlled “wanghong” economy, a marked shift from the earlier, more unregulated era of livestreaming. While some view these measures as restrictive, many commenters support the tighter oversight.

A well-known Kuaishou influencer, who collaborates with a person with dwarfism, recently faced backlash for sharing “vulgar content,” including videos where he kicks his collaborator (see video) or stages sensational scenes just for attention.

Most commenters welcome the recent wave of criticism and actions taken against such influencers, including Xiaohuxing and Dongbei Yujie, for their behavior. “It’s easy to become famous and make money like this,” commenters noted, adding, “It’s good to see the industry getting cleaned up.”

State media outlet People’s Daily echoed this sentiment in an October 21 commentary, stating, “No matter how many fans you have or how high your traffic is, legal lines must not be crossed. Those who cross the red line will ultimately pay the price.”

This article and recent incidents have sparked more online discussions about the kind of influencers needed in the livestreaming era. Many suggest that, beyond adhering to legal boundaries, celebrity livestreamers should demonstrate a higher moral standard and responsibility within this digital landscape. “We need positive energy, we need people who are authentic,” one Weibo user wrote.

Others, however, believe misbehaving “wanghong” livestreamers naturally face consequences: “They rise fast, but their popularity fades just as quickly.”

When asked, “What kind of influencers do we need?” one commenter responded, “We don’t need influencers at all.”

By Wendy Huang

Follow @whatsonweibo

Edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

China Arts & Entertainment

The Rising Influence of Fandom Culture in Chinese Table Tennis

The match between Sun Yingsha and Chen Meng in Paris highlighted how the fan culture surrounding Chinese table tennis can clash with the Olympic spirit.

Published

6 months agoon

August 16, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

During the Paris Olympics, not a day went by without table tennis making its way onto Weibo’s trending lists. The Chinese table tennis team achieved great success, winning five gold medals and one silver.

However, the women’s singles final on August 3rd, between Chinese champions Chen Meng (陈梦) and Sun Yingsha (孙颖莎), took viewers by surprise due to the unsettling atmosphere. The crowd overwhelmingly supported Sun Yingsha, with little applause for Chen Meng, and some hurled insults at her. Even the coaching staff had stern expressions after Chen’s win.

This bizarre scene sparked heated discussions on Chinese social media, exposing the broader audience to the chaotic and sometimes absurd dynamics within China’s table tennis fandom.

“I welcome fans but reject fandom culture.”

When Sun Yingsha and Chen Meng faced off in the women’s singles final, the medal was destined for ‘Team China’ regardless of the outcome; the match should have been a celebration of Chinese table tennis.

However, the match held significant importance for both Sun and Chen individually. Chen Meng, the defending champion from the previous Olympics, was on the verge of making history by retaining her title. Meanwhile, Sun Yingsha, an emerging star who had already claimed singles titles at the World Cup and World Championships, was aiming to complete a career Grand Slam (World Championships, World Cup, and Olympics).

[center] Announcement of the Chen (L) vs Sun (R) match by People’s Daily on social media.[/center]

Sun Yingsha has clearly become a public favorite. On Weibo, the table tennis star ranked among the most beloved athletes in popularity lists.

This favoritism among Chinese table tennis fans was evident at the venue. According to reports from a Chinese audience member, anyone shouting “Go Chen Meng!” (“陈梦加油”) was quickly silenced or booed, while even cheering “Come on China!” (“中国队加油”) was met with ridicule. After Chen Meng’s 4-2 victory, many in the audience expressed their frustration and chanted “refund” during the award ceremony. Meanwhile, social media was flooded with hateful posts cursing Chen for winning the match.

For many who were unfamiliar with the off-court drama, the influence of fandom culture on the Olympics was shocking. However, in the world of Chinese table tennis, such extreme fan behavior has been brewing for some time. Even during the eras of Ma Long (马龙) and Zhang Jike (张继科), there were already fans who would turn against each other and others.

This year’s men’s singles champion, Fan Zhendong (樊振东), had long noticed the growing influence of fandom culture. In recent years, he has repeatedly voiced his discomfort with fan activities like “airport send-offs” and “fan meet-and-greets.” Earlier this year, he took to social media to reveal that he and his loved ones were being harassed by both overzealous fans and haters, and that he was considering legal action. He made it clear: “I welcome fans but reject fandom culture.” His consistent stance against fandom has helped cultivate a relatively rational fan base.

“What has happened to Chinese table tennis fans over the years?”

On Weibo, a blogger (@3号厅检票员工) posed a question that struck a chord with many, garnering over 30,000 likes: “What has happened to Chinese table tennis fans over the years?”

In the comments, many blamed Liu Guoliang (刘国梁) for fueling the fan culture around table tennis. Liu, the first Chinese male player to achieve the Grand Slam, retired in 2002 and then became a coach for the Chinese table tennis team. His coaching career has been highly successful, leading players like Ma Long and Xu Xin (许昕) to numerous championships.

Beyond coaching, Liu has been dedicated to commercializing table tennis. Compared to international tournaments in sports like tennis or golf, the prize money for Chinese table tennis players is only about one-tenth of those sports. Fan Zhendong has publicly stated on Weibo that the prize money for their competitions is too low compared to badminton. Liu believes table tennis has significant untapped commercial potential that has yet to be fully realized.

Under Liu’s leadership, the commercialization of the Chinese table tennis team began after the Rio Olympics, where China won all four gold medals. Viral internet memes like “Zhang Jike, wake up!” (继科你醒醒啊) and “The chubby guy who doesn’t understand the game” (不懂球的胖子) made both the sport and its athletes wildly popular in China.

Seeing the opportunity, Liu quickly increased the team’s exposure, encouraging players to create Weibo accounts, do live streams, star in films, and participate in variety shows. This approach rapidly turned the Chinese table tennis team into a “super influencer” in the Chinese sports world.

While this move has certainly increased the athletes’ visibility, it has also drawn criticism: is this kind of commercialization and celebrity status the right path for China’s table tennis? Successful commercialization requires a mature system for talent selection, team building, and athlete management. However, the selection process in Chinese table tennis remains opaque, the current team-building system shows little promise, and young athletes struggle to break through.

Additionally, athlete management appears amateurish. After watching an interview with Chinese tennis player Zheng Qinwen (郑钦文), a Douban netizen commented that Liu Guoliang’s plan for commercializing athletes is highly unprofessional—relying mainly on their personal charisma to attract attention. The most common criticism is that Liu and the Table Tennis Association should let professionals handle the professional work. Without a solid foundation for commercialization, the current focus on hype and marketing in Chinese table tennis may temporarily boost ticket sales but could ultimately backfire.

“Didn’t you say you want to crack down on fan culture?”

In response to the controversy surrounding the Chen vs. Sun match, the Beijing Daily published an article titled “How Can We Allow Fandom Violence to Disturb the World of Table Tennis?” The article addressed the growing problem of “fandom culture” infiltrating table tennis, a trend that originated in the entertainment world. It highlighted how extreme fan behavior, including online abuse and disruptive actions during matches, harms both the sport and the mental well-being of athletes. While fan enthusiasm is important, the article stressed that it must remain within rational limits.

This article foreshadowed actions taken shortly after. On August 7th, China’s Ministry of Public Security announced an online crackdown on chaotic sports-related fan circles. Social media platforms responded swiftly: Weibo deleted over 12,000 posts and banned more than 300 accounts, while Xiaohongshu, Bilibili, and Migu Video removed over 840,000 posts and banned or muted more than 5,300 accounts.

The campaign against fan culture sparked online debate. Some netizens criticized the official stance on “fandom” as overly simplistic. The Chinese term for “fandom,” 饭圈 (fànquān), contains a homophone for “fan,” referring to enthusiastic supporters of celebrities. In contemporary Chinese discourse, the term is often linked to the idol industry and carries negative, gender-biased connotations, particularly towards “irrational female fans chasing male idols.”

One Weibo post argued that commercialized sports, like football, are inherently tied to fan loyalty, belonging, and exclusivity. Disruptions among fans are not solely due to “fandom” but are often influenced by larger forces, such as capital or authorities. In the table tennis final, even the coaching team’s dissatisfaction with Chen Meng’s victory points to underlying problems beyond fan behavior.

While public backlash against “fandom” in sports often stems from concerns over its toxicity and violence, as blogger Yuyu noted, internal conflicts and power struggles have always existed in competitive sports. Framing these issues solely as “fandom problems” risks oversimplifying the situation and overlooks challenges such as commercialization failures, poor youth development, and internal factionalism within sports teams. The simplistic blame on “fandom culture” is seen by some as a distraction from these real issues, further fueling public frustration.

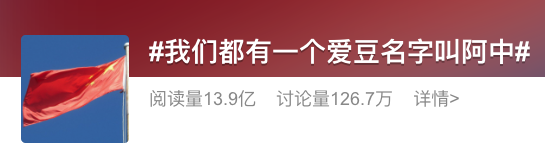

This public frustration is evident in a 2019 Weibo post and hashtag from People’s Daily. The five-year-old post personified China as a young male idol, promoting patriotism through fandom culture with the slogan “We all have an idol named ‘A Zhong’ (#我们都有一个爱豆名字叫阿中#)” [‘A Zhong’ was used as a nickname to refer to a personified China]. This promotion of ‘China’ as an idol with a 1.4 billion ‘fandom’ resurfaced during the Hong Kong protests.

Hashtag: “We all have an idol named Azhong” [nickname for China]

Now, after state media harshly criticized fandom culture, netizens have revisited the post, bringing it back into the spotlight. Recent comments on the post are filled with sarcasm, highlighting how fandom is apparently embraced when convenient and scapegoated when problems arise.

Post by People’s Daily promoting China as an “idol.”

“Didn’t you say you wanted to crack down on fan culture?” one commenter wondered.

Chen Meng, the Olympic table tennis champion, has also addressed the fan culture surrounding the 2024 Paris matches. She expressed her hope that, in the future, fans will focus more on the athletes’ “fighting spirit” on the field. True sports fans, she suggested, should be able to celebrate when their favorite athlete wins and accept it when they lose. “Because that’s precisely what competitive sports are all about,” she said.

By Ruixin Zhang

edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

What’s on Weibo Chapters

Subscribe

The Unstoppable Success of Ne Zha 2: Breaking Global Records and Sparking Debate on Chinese Social Media

From Weibo to RedNote: The Ultimate Short Guide to China’s Top 10 Social Media Platforms

Collective Grief Over “Big S”

Tuning Into the Year of the Snake

The ‘China-chic Girl’ Image and the Realities of China’s Competitive Food Delivery Market

Our Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Why Chinese Hit Movie “Her Story” is ‘Good Stuff’: Stirring Controversy and Celebrating Female Perspectives

Chiung Yao’s Suicide Farewell Letter: An English Translation

12-Year-Old Girl from Shandong Gets Infected with HPV: Viral Case Exposes Failures in Protecting Minors

Breaking the Taboo: China’s Sanitary Pad Controversy Sparks Demand for Change

Weibo Watch: Christmas in China Is Everywhere and Nowhere

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

Weibo Watch: China’s Online Feminism Is Everywhere

Story of Chinese Female MA Graduate Going Missing for 13 Years Sparks Online Storm

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight10 months ago

China Insight10 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music11 months ago

China Music11 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Insight12 months ago

China Insight12 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Digital9 months ago

China Digital9 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI