China Arts & Entertainment

Chinese Idol Survival Shows – The Start of a New ‘Idol Era’

Idol reality survival shows are riding a new wave of popularity in China.

Published

5 years agoon

China has a vibrant online popular culture media environment, where new trends and genres come and go every single day. Chinese idol survival shows, however, have seen continued success and now seem to go through another major peak in popularity. What’s on Weibo’s Yin Lin explains.

On May 30, the finale of Chinese online video platform iQIYI’s Youth With You 2 (青春有你2) broke the Internet. Official videos on iQIYI’s Youtube channel garnered over 300 million views. At the time of writing, the hashtag “Youth With You 2 Finale” (#青春有你2总决赛#) has 3.15 billion views; the hashtag “Youth With You 2” (#青春有你2#) has 14.5 billion views.

In recent years, China has produced a slew of so-called ‘idol survival shows.’ They have enjoyed much popularity among local audiences, as well as overseas—more than 393 hashtags related to Youth With You 2 trended in Asia, Europe, South America, and North America. In this overview, we explore the background, status quo, and future of China’s idol survival shows.

The Start of The ‘Idol Wave’ in China

In China’s idol survival reality shows, so-called ‘trainees’, or aspiring idols, participate in a series of different challenges to compete for a chance to debut.

The ‘idol culture’ (偶像文化) has been dominating popular culture in Japan and South Korea for many years. An idol is, in short, a heavily commercialized multi-talented entertainer that is marketed – sometimes as a product – for image, attractiveness, and personality, either alone or with a group.

Especially K-pop and the Korean entertainment industry have since long been extremely popular among Chinese youth, heavily influencing pop culture in China today (more about Korean and Japanese idols here and here, and also read our article “Why Korean Idol Groups Got So Big in China and are Conquering the World“).

These kinds of shows are ubiquitous in South Korea’s popular culture, with Produce 101 (2016) becoming one of the most popular and successful South Korean reality series ever.

The concept is simple. Every week, viewers vote for their favorite contestant. Trainees with insufficient votes during elimination rounds are eliminated from the competition.

Nine Percent, the group formed from Idol Producer (Source).

The group formed from the final trainees then goes on to ‘promote’ for a period of time, usually one to two years.

This method of creating an idol group, in which the members are basically selected by their own fans, is a major way to bridge existing distances between fans and their idols. Fan participation is a key factor in the success of idol reality shows.

While China has had several idol survival shows, iQIYI’s Idol Producer (青春有你, 2018) was the first to reach levels of popularity similar to that of South Korea’s Produce 101.

Idol Producer premiered in January 2018 with Zhang Yixing as the host and Li Ronghao, MC Jin, Cheng Xiao, Zhou Jieqiong, and Jackson Wang serving as mentors.

This first season of Idol Producer brought together a total of hundred trainees. Though most trainees were from China, there were a few from overseas, such as You Zhangjing from Malaysia and Huang Shuhao from Thailand. The younger brother of Chinese actress Fan Bingbing, Fan Chengcheng, also participated in the show.

The first episode of Idol Producer attracted more than 100 million views within the first hour of broadcasting. In the final episode, more than 180 million votes were cast, with first-place winner Cai Xukun raking in more than 47 million votes.

Trainees performing on Produce 101 China (Source).

Two months after Idol Producer, Tencent launched Produce 101 China (创造101) in March 2018. Both shows marked the start of the ‘idol wave’ in China.

In the next two years, more idol survival shows would dominate the Chinese entertainment scene. iQIYI released Youth With You 1 (青春有你) and Youth With You 2 (青春有你2) in 2019 and 2020 respectively. Tencent, too, released Produce Camp 2019 (创造营2019) and Produce Camp 2020 (创造营2020), the latter of which is currently airing.

China’s New Idol Survival Show Era

In 2018, both Produce 101 China and Idol Producer enjoyed overwhelming popularity, accumulating more than 4.73 billion views and 3 billion views respectively. Their sequels, however, have failed to achieve the same level of success.

At the time of writing, 150,000 viewers have completed Youth With You 1 on Chinese community site Douban, versus 470,000 viewers for its predecessor, Idol Producer. Additionally, the number of votes cast for the first episode of Youth With You 1 was much lower compared to its Idol Producer equivalent.

The number of votes for the top 19 trainees on Idol Producer (left) versus Youth With You 1 (right) in the first episode (Source).

As for Produce 101 China, 510,000 viewers have completed the show on Douban, but only 340,000 viewers have finished watching its sequel.

Groups formed from these shows have met with varying amounts of success and have run into problems regarding scheduling conflicts.

Nine Percent, the boy group formed from Idol Producer in 2018, was known as a group that rarely met. Their second album was a compilation of tracks from solo members. Members had existing contracts with their own companies while simultaneously promoting with Nine Percent; hence, due to scheduling conflicts, members would often forgo Nine Percent activities for those of their own company.

Rocket Girls from Produce 101 China. (Source)

Rocket Girls, formed from Produce 101 China, also faced problems after debuting. Due to conflicts between Tencent and their management company, Yuehua Entertainment, Meng Meiqi and Wu Xuanyi, who placed first and second respectively, left the group two months after debut.

Despite the problems faced by groups formed from such shows, some idols were able to ride on the momentum they gained from participating.

For instance, Cai Xukun, first-place winner of Idol Producer, swiftly rose to become one of the most popular trainees on the show, consistently ranking first place in every round of elimination. He was also the host of the recently concluded Youth With You 2.

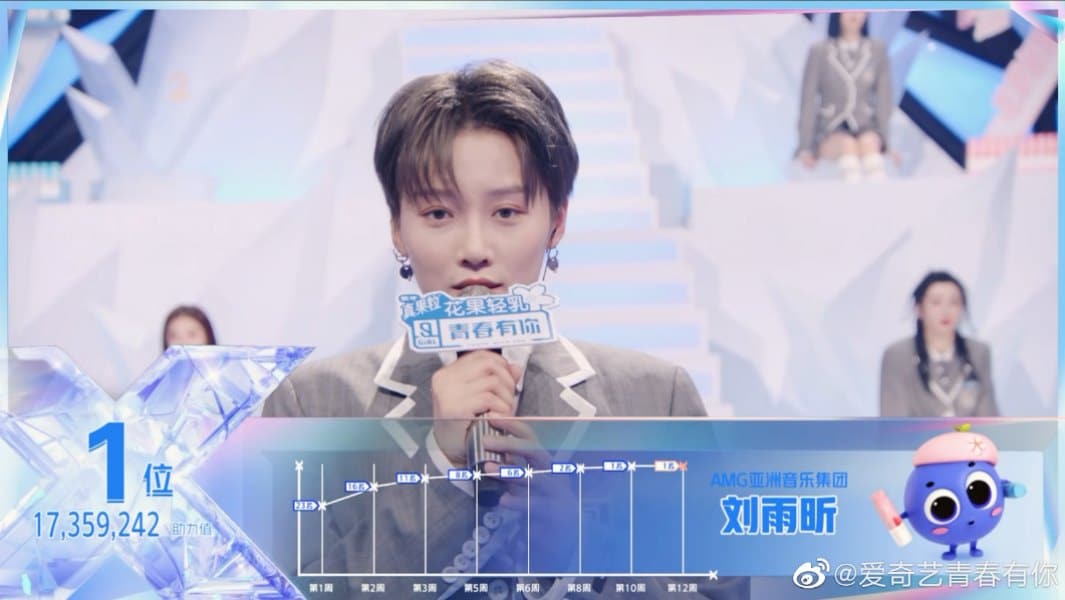

Liu Yuxin obtained first place in the last episode of Youth With You 2. (Source)

Other trainees have also seen individual success. Liu Yuxin, the first-place winner of Youth With You 2, gained attention for her androgynous look: short hair, a cool personality, and wearing shorts instead of a skirt. Her hashtag “Liu Yuxin” (#刘雨昕#) has been viewed more than 550 million times on Weibo. In the final episode, she received more than 17 million votes.

Despite the lowering audience ratings for other recent idol shows, the success of Youth With You 2 might mark the start of a new ‘idol era’. Even Chinese netizens wondered why the show is so popular compared to Youth With You 1.

Just one day after the finale premiered, the hashtag “Youth With You 2 Finale” had already been viewed more than 2.2 billion times on Weibo. On Douban, 580,000 viewers have finished the show—more than any of the previous idol survival shows by iQIYI and Tencent.

The Future of Idol Survival Shows

Chinese idol survival shows were received with much fanfare when they first entered mainstream popular culture in 2018. But the ensuing conflicts that the resulting groups ran into resulted in netizens doubting the success and effectiveness of these shows.

Trainees from Produce Camp 2020 practicing for the theme song. Source

This year, however, the popularity of both Youth With You 2 and Produce Camp 2020 might signal a comeback for the idol era in China.

And this time around, Chinese idol survival shows are also gaining more traction outside of the PRC, becoming more and more popular among global audiences. Both Youth With You 2 and Produce Camp 2020 have been well-received by viewers from many different countries.

On social media, online commenters praise the two shows – and Chinese idol survival shows in general – for having a more “laid-back atmosphere” between the trainees and mentors. Web users also comment that they enjoy how the shows highlight the friendship between the trainees, rather than the feuds.

It seems that what sets Chinese idol survival shows apart from the South Korean ones is precisely why some viewers prefer them. The longer running times, for example, makes it possible to give more screen time to the different trainees and to give a deeper understanding of the relations between them.

Youtube comment on Episode 1 of Produce Camp 2020. Source

Youtube comment on Episode 1 of Produce Camp 2020. Source

Reddit comment on Episode 9 of Idol Producer. Source

With the popularity of idols like Liu Yuxin and Wang Ju who challenge conventional beauty standards, shows can also look into moving away from the cookie-cutter aesthetic that idols usually adhere to.

Furthermore, management companies and broadcasting companies have to come to an agreement regarding what scheduling arrangement would benefit all parties and be conducive towards the idols’ physical and mental health.

Selected trainees from Produce Camp 2020 took part in a photoshoot with Elle. Source

It remains to be seen whether THE9, the newly formed group from Youth With You 2, will be able to flourish in the time to come and avoid the troubles that other groups ran into.

As for Produce Camp 2020, it seems set to enjoy just as much success as Youth With You 2 did – if not more. Only five episodes have been released, but the show’s hashtag already has 16.1 billion views.

A reviewer on Douban writes: “The trainees are all confident, taking opportunities to express themselves and actively showcase their talents. So much youthful and positive energy!”

The latest newcomers to the idol reality show genre further consolidate the success of the format. Recently, Mango TV released Sisters Who Make Waves (乘风波浪的姐姐们, 2020), where female celebrities above 30 years old compete to make it into the final five-member girl group. The first episode was viewed more than 370 million times within the first three days of release and immediately became top trending on Weibo.

The number of survival shows in China right now and their growing popularity shows that audiences seemingly can’t get enough of the genre. It is an indication that, despite setbacks in the past, China’s idol survival reality show genre is still going strong and might be here to stay.

You can watch the currently airing Produce Camp 2020 and Sisters Who Make Waves here and here.

By Yin Lin Tan

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2020 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Yin Lin Tan is a Singapore-based writer and aspiring journalist specialized in culture and current affairs. She is particularly interested in exploring issues related to East Asia, with a special focus on China. Yin Lin can be reached at tylanin[at]gmail[dot]com.

You may like

China Arts & Entertainment

How K-pop Fans and the 13-Year-Old Daughter of Baidu VP Sparked a Debate on Online Privacy

What began as K-pop fan outrage targeting a snarky commenter quickly escalated into a Baidu-linked scandal and a broader conversation about data privacy on Chinese social media.

Published

4 days agoon

March 26, 2025By

Ruixin Zhang

For an ordinary person with just a few followers, a Weibo account can sometimes be like a refuge from real life—almost like a private space on a public platform—where, along with millions of others, they can express dissatisfaction about daily annoyances or vent frustration about personal life situations.

But over recent years, even the most ordinary social media users could become victims of “opening the box” (开盒 kāihé)—the Chinese internet term for doxxing, meaning the deliberate leaking of personal information to expose or harass someone online.

A K-pop Fan-Led Online Witch Hunt

On March 12, a Chinese social media account focusing on K-pop content, Yuanqi Taopu Xuanshou (@元气桃浦选手), posted about Jang Wonyoung, a popular member of the Korean girl group IVE. As the South Korean singer and model attended Paris Fashion Week and then flew back the same day, the account suggested she was on a “crazy schedule.”

In the comment section, one female Weibo user nicknamed “Charihe” replied:

💬 “It’s a 12-hour flight and it’s not like she’s flying the plane herself. Isn’t sleeping in business class considered resting? Who says she can’t rest? What are you actually talking about by calling this a ‘crazy schedule’..”

Although the comment may have come across as a bit snarky, it was generally lighthearted and harmless. Yet unexpectedly, it brought disaster upon her.

That very evening, the woman nicknamed Charihe was bombarded with direct messages filled with insults from fans of Jang Wonyoung and IVE.

Ironically, Charihe’s profile showed she was anything but a hater of the pop star—her Weibo page included multiple posts praising Wonyoung’s beauty and charm. But that context was ignored by overzealous fans, who combed through her social media accounts looking for other posts to criticize, framing her as a terrible person.

After discovering through Charihe’s account that she was pregnant, Jang Wonyoung’s fans escalated their attacks by targeting her unborn child with insults.

The harassment did not stop there. Around midnight, fans doxxed Charihe, exposing her personal information, workplace, and the contact details of her family and friends. Her friends were flooded with messages, and some were even targeted at their workplaces.

Then, they tracked down Charihe’s husband’s WeChat account, sent him screenshots of her posts, and encouraged him to “physically punish” her.

The extremity of the online harassment finally drew backlash from netizens, who expressed concern for this ordinary pregnant woman’s situation:

💬 “Her entire life was exposed to people she never wanted to know about.”

💬 “Suffering this kind of attack during pregnancy is truly an undeserved disaster.”

Despite condemnation of the hate, some extreme self-proclaimed “fans” remained relentless in the online witch hunt against Charihe.

Baidu Takes a Hit After VP’s 13-Year-Old Daughter Is Exposed

One female fan, nicknamed “YourEyes” (@你的眼眸是世界上最小的湖泊), soon started doxxing commenters who had defended her. The speed and efficiency of these attacks left many stunned at just how easy it apparently is to trace social media users and doxx them.

Digging into old Weibo posts from the “YourEyes” account, people found she had repeatedly doxxed people on social media since last year, using various alt accounts.

She had previously also shared information claiming to study in Canada and boasted about her father’s monthly salary of 220,000 RMB (approx. $30.3K), along with a photo of a confirmation document.

Piecing together the clues, online sleuths finally identified her as the daughter of Xie Guangjun (谢广军), Vice President of Baidu.

From an online hate campaign against an innocent, snarky commenter, the case then became a headline in Chinese state media, and even made international headlines, after it was confirmed that the user “YourEyes”—who had been so quick to dig up others’ personal details—was in fact the 13-year-old daughter of Xie Guangjun, vice president at one of China’s biggest tech giants.

On March 17, Xie Guangjun posted the following apology to his WeChat Moments:

💬 “Recently, my 13-year-old daughter got into an online dispute. Losing control of her emotions, she published other people’s private information from overseas social platforms onto her own account. This led to her own personal information also getting exposed, triggering widespread negative discussion.

As her father, I failed to detect the problem in time and failed to guide her in how to properly handle the situation. I did not teach her the importance of respecting and protecting the privacy of others and of herself, for which I feel deep regret.

In response to this incident, I have communicated with my daughter and sternly criticized her actions. I hereby sincerely apologize to all friends affected.

As a minor, my daughter’s emotional and cognitive maturity is still developing. In a moment of impulsiveness, she made a wrong decision that hurt others and, at the same time, found herself caught in a storm of controversy that has subjected her to pressure and distress far beyond her age.

Here, I respectfully ask everyone to stop spreading related content and to give her the opportunity to correct her mistakes and grow.

Once again, I extend my apologies, and I sincerely thank everyone for your understanding and kindness.”

The public response to Xie’s apology has been largely negative. Many criticized the fact that it was posted privately on WeChat Moments rather than shared on a public platform like Weibo. Some dismissed the statement as an attempt to pacify Baidu shareholders and colleagues rather than take real accountability.

Netizens also pointed out that the apology avoided addressing the core issue of doxxing. Concerns were raised about whether Xie’s position at Baidu—and potential access to sensitive information—may have helped his daughter acquire the data she used to doxx others.

Adding fuel to the speculation were past conversations allegedly involving one of @YourEyes’ alt accounts. In one exchange, when asked “Who are you doxxing next?” she replied, “My parents provided the info,” with a friend adding, “The Baidu database can doxx your entire family.”

Following an internal investigation, Baidu’s head of security, Chen Yang (陈洋), stated on the company’s internal forum that Xie Guangjun’s daughter did not obtain data from Baidu but from “overseas sources.”

However, this clarification did little to reassure the public—and Baidu’s reputation has taken a hit. The company has faced prior scandals, most notably a the 2016 controversy over profiting from misleading medical advertisements.

Online Vulnerability

Beyond Baidu’s involvement, the incident reignited wider concerns about online privacy in China. “Even if it didn’t come from Baidu,” one user wrote, “the fact that a 13-year-old can access such personal information about strangers is terrifying.”

Using the hashtag “Reporter buys own confidential data” (#记者买到了自己的秘密#), Chinese media outlet Southern Metropolis Daily (@南方都市报) recently reported that China’s gray market for personal data has grown significantly. For just 300 RMB ($41), their journalist was able to purchase their own household registration data.

Further investigation uncovered underground networks that claim to cooperate with police, offering a “70-30 profit split” on data transactions.

These illegal data practices are not just connected to doxxing but also to widespread online fraud.

In response, some netizens have begun sharing guides on how to protect oneself from doxxing. For example, they recommend people disable phone number search on apps like WeChat and Alipay, hide their real name in settings, and avoid adding strangers, especially if they are active in fan communities.

Amid the chaos, K-pop fan wars continue to rage online. But some voices—such as influencer Jingzai (@一个特别虚荣的人)—have pointed out that the real issue isn’t fandom, but the deeper problem of data security.

💬 “You should question Baidu, question the telecom giants, question the government, and only then, fight over which fan group started this.”

As for ‘Charihe,’ whose comment sparked it all—her account is now gone. Her username has become a hashtag. For some, it’s still a target for online abuse. For others, it is a reminder of just how vulnerable every user is in a world where digital privacy is far from guaranteed.

By Ruixin Zhang

Independently covering digital China for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Memes & Viral

How Ne Zha 2’s Shen Gongbao Became Known as the Ultimate “Small-Town Swot”

Published

4 weeks agoon

March 1, 2025

PART OF THIS TEXT COMES FROM THE WEIBO WATCH PREMIUM NEWSLETTER

Over the past few weeks, the Chinese blockbuster Ne Zha 2 has been trending on Weibo every single day. The movie, loosely based on Chinese mythology and the Chinese canonical novel Investiture of the Gods (封神演义), has triggered all kinds of memes and discussions on Chinese social media (read more here and here).

One of the most beloved characters is the leopard demon Shen Gongbao (申公豹). While Shen Gongbao was a more typical villain in the first film, the narrative of Ne Zha 2 adds more nuance and complexity to his character. By exploring his struggles, the film makes him more relatable and sympathetic.

In the movie, Shen is portrayed as a sometimes sinister and tragic villain with humorous and likeable traits. He has a stutter, and a deep desire to earn recognition. Unlike many celestial figures in the film, Shen Gongbao was not born into privilege and never became immortal. As a demon who ascended to the divine court, he remains at the lower rungs of the hierarchy in Chinese mythology. He is a hardworking overachiever who perhaps turned into a villain due to being treated unfairly.

Many viewers resonate with him because, despite his diligence, he will never be like the gods and immortals around him. Many Chinese netizens suggest that Shen Gongbao represents the experience of many “small-town swots” (xiǎozhèn zuòtíjiā 小镇做题家) in China.

“Small-town swot” is a buzzword that has appeared on Chinese social media over the past few years. According to Baike, it first popped up on a Douban forum dedicated to discussing the struggles of students from China’s top universities. Although the term has been part of social media language since 2020, it has recently come back into the spotlight due to Shen Gongbao.

“Small-town swot” refers to students from rural areas and small towns in China who put in immense effort to secure a place at a top university and move to bigger cities. While they may excel academically, even ranking as top scorers, they often find they lack the same social advantages, connections, and networking opportunities as their urban peers.

The idea that they remain at a disadvantage despite working so hard leads to frustration and anxiety—it seems they will never truly escape their background. In a way, it reflects a deeper aspect of China’s rural-urban divide.

Some people on Weibo, like Chinese documentary director and blogger Bianren Guowei (@汴人郭威), try to translate Shen Gongbao’s legendary narrative to a modern Chinese immigrant situation, and imagine that in today’s China, he’d be the guy who trusts in his hard work and intelligence to get into a prestigious school, pass the TOEFL, obtain a green card, and then work in Silicon Valley or on Wall Street. Meanwhile, as a filial son and good brother, he’d save up his “celestial pills” (US dollars) to send home to his family.

Another popular blogger (@痴史) wrote:

“I just finished watching Ne Zha and my wife asked me, why do so many people sympathize with Shen Gongbao? I said, I’ll give you an example to make you understand. Shen Gongbao spent years painstakingly accumulating just six immortal pills (xiāndān 仙丹), while the celestial beings could have 9,000 in their hand just like that.

It’s like saving up money from scatch for years just to buy a gold bracelet, only to realize that the trash bins of the rich people are made of gold, and even the wires in their homes are made of gold. It’s like working tirelessly for years to save up 60,000 yuan ($8230), while someone else can effortlessly pull out 90 million ($12.3 million).In the Heavenly Palace, a single meal costs more than an ordinary person’s lifetime earnings.

Shen Gongbao seems to be his father’s pride, he’s a role model to his little brother, and he’s the hope of his entire village. Yet, despite all his diligence and effort, in the celestial realm, he’s nothing more than a marginal figure. Shen Gongbao is not a villain, he is just the epitome of all of us ordinary people. It is because he represents the state of most of us normal people, that he receives so much empathy.”

In the end, in the eyes of many, Shen Gongbao is the ultimate small-town swot. As a result, he has temporarily become China’s most beloved villain.

By Manya Koetse, with contributions by Wendy Huang

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Subscribe

How K-pop Fans and the 13-Year-Old Daughter of Baidu VP Sparked a Debate on Online Privacy

Squat or Sit? China’s Great Toilet Debate and the Problem of Footprints on the Seat

Weibo Watch: The Great Squat vs Sitting Toilet Debate in China🧻

Chinese Netizens Turn to Tim Cook Over Battery Factory’s Illegal Overtime

Revisiting China’s Most Viral Resignation Letter: “The World Is So Big, I Want to Go and See It”

Our Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Beyond the Box Office: What’s Behind Ne Zha 2’s Success?

Weibo Watch: Christmas in China Is Everywhere and Nowhere

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

15 Years of Weibo: The Evolution of China’s Social Media Giant

Tuning Into the Year of the Snake

The ‘China-chic Girl’ Image and the Realities of China’s Competitive Food Delivery Market

TikTok Refugees, Xiaohongshu, and the Letters from Li Hua

“Black Myth: Wukong”: From Gaming Screens to the CMG Spring Festival Gala?

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight11 months ago

China Insight11 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music12 months ago

China Music12 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

-

China Arts & Entertainment11 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment11 months agoSinging Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments