China Media

Chinese State Media Features German Twitterer “Defamed by Evil Western Forces”

European media call the 21-year-old Heyden a CCP propagandist, Chinese media call her a victim of the Western media agenda.

Published

4 years agoon

The German influencer Navina Heyden has been labeled “a propagandist for the Chinese government” by European media outlets. She is now featured by Global Times for preparing a lawsuit against German newspaper Die Welt for “defaming” her.

A 21-year-old woman from Germany has been attracting attention on Chinese social media this week after state media outlet Global Times published an article about her battle against “biased journalism” in Europe.

She is known by her Chinese name of Hǎiwénnà 海雯娜 on Weibo, but also by her German name, Navina Heyden. On Twitter (@NavinaHeyden) she has around 34K followers, on Weibo (@海雯娜NavinaHeyden) she has over 15800 fans.

According to the Global Times story, which is titled “21-year-old German Girl Debunking China’s Defamation Is Tragically Strangled by Evil Western Forces” [“21岁德国女孩驳斥对中国抹黑,惨遭西方恶势力绞杀”], Heyden has been on a mission to “refute Western media’s smear campaign against China” for the past year.

The same article was also published by other Chinese state media outlets this week, including Xinhua, Xinmin, and Beijing Times.

Recently, various European news outlets reporting about Heyden’s online activities described her as a Twitter influencer acting as an advocate for “pro-CCP narratives.”

It started with the German newspaper Welt am Sonntag publishing an article on June 15 of 2021 titled “China’s Secret Propagandists” [“Chinas Heimliche Propagandisten”], in which Heyden was accused of being a propagandist. That same story was translated into French and published by Le Soir on June 23.

An article by London-based think tank ISD (Institute for Strategic Dialogue) dated June 10, titled “How a Pro-CCP Twitter Network is Boosting the Popularity of Western Influencers” (link), also featured Heyden and her alleged role in a coordinated Chinese online propaganda campaign.

The article focuses on Heyden’s Twitter activity and her supposedly inorganic follower growth, using data research to support the claim that she is more than just a young woman siding with Chinese official views.

Heyden claims that she agreed to do the initial interview with Die Welt about her views on China and the online harassment she experienced by anti-China activists, but that the reporters eventually published something that was very different from the actual interview content, describing Heyden as a Chinese government propagandist and disclosing names and locations without her consent.

Heyden says she is now preparing a lawsuit against the newspaper and its three journalists for violating her rights. In order to do so, she started a crowdfunding campaign to help her fight media defamation. That ‘Go Fund Me’ campaign was also promoted on Weibo on July 5th, and she soon reached over 13,000 euros in donations.

The main take-away of the Global Times story is that Heyden is an active social media user who has bravely refuted Western bias on China and exposed the supposed media hysteria regarding the rise of China, and that she has been purposely targeted by European media outlets for doing so.

Heyden joined Twitter in March of 2020 with her bio describing her as a “German amateur manga drawer, studying business economy, grown up within Chinese community since age 15.”

Since then, she has tweeted over 1000 times and has spoken out about many issues involving China, including the Covid-19 pandemic, the situation in Xinjiang, the national security law in Hong Kong, the India-China border conflict, and the status of Taiwan. She sometimes also tweets out more personal information, such as the time when she shared photos of herself and her Chinese partner.

Her very first tweet on the platform – one about China not falsifying Covid-19 numbers – was sent out on April 1st of 2020 and received 52 likes. Over the past year, her account has only gained more likes and followers.

A later tweet in which Heyden wrote “I can testify that Chinese Muslims are not persecuted like what western media claimed” (link) received over 870 likes.

In another tweet, Heyden wrote: “China is unfairly treated because she’s always put in a trial without chances to defend. Her words must be propaganda, her people must be brainwashed. After confirmation with Chinese sources and my experiences, I’m enraged about how wrong our media is. This is harmful to us all.” That tweet received over 1.4K likes.

Besides the fact that Heyden’s tweets are often retweeted by the Twitter accounts of Chinese diplomats and other prominent Chinese channels – sometimes within just a few seconds of one another, – the aforementioned ISD article claims that Heyden’s account has grown in a relatively short time due to sudden spikes in followership by accounts that were created in batches at specific times and in short sequence.

For a Twitter post of August 2020, Heyden recorded a video in which she explained why she wanted to open up her Twitter account in the first place and counter those accusing her of being a “CCP agent” or a “fake account”. She said:

“I’m not getting paid by anyone so stop wasting your time on proving something which I am not. A lot of people may wonder why I say so many positive things about China in the first place. The reason is that when I was around 15 years old I was introduced into the Chinese community and I got to learn a lot of Chinese people, what they think about China, and also what they think about their government. And I found that the China I visited is so much different from the China that the media is describing. It’s almost as if the media is describing a whole different country. Now, it wouldn’t be so bad if only people would not buy those false narratives, and I’m having a problem with it, because a lot of my close friends and also my family are believing all those false narratives. And this is causing me to have some conflicts with them from time to time. So I’ve decided to open this Twitter account to debunk all those false narratives.”

At this time, Heyden describes her own Twitter account as “one of the most influential ones to show people what real China is like.”

The story about Heyden’s online activities seems to suit some ongoing narratives in both European and Chinese newspapers. For the first, it upholds the idea of China secretly attempting to infiltrate and influence democratic societies in new ways; for the latter, it confirms the belief that biased Western media will do anything to defile China while serving the interests of their political parties.

Meanwhile, on Weibo, hundreds of netizens have praised Heyden for defending China and standing up against Western media.

“China has 1.4 billion people, Germany just has [tens] millions, of course, you’re gonna get a lot of fans if you support China,” one popular comment on Weibo said.

One influential Weibo blogger (@文创客) wrote about Heyden, calling her a victim of a “deranged” situation where Western media outlets have used her for their anti-China narratives.

“When will you come and live in China,” some people on Weibo ask, with various other commenters saying: “Just come to China!”

Plans to move to China seem to be on the horizon for the German influencer. In an earlier tweet, she confirmed: “We are already on the path to live in China PERMANENTLY. Really feel much safer there.”

Despite sharing her strong support for China on Twitter, the 21-year-old recently also expressed some frustrations with the Chinese social media climate when she encountered censorship on Sina Weibo and experienced some difficulties posting on Bilibili and Toutiao.

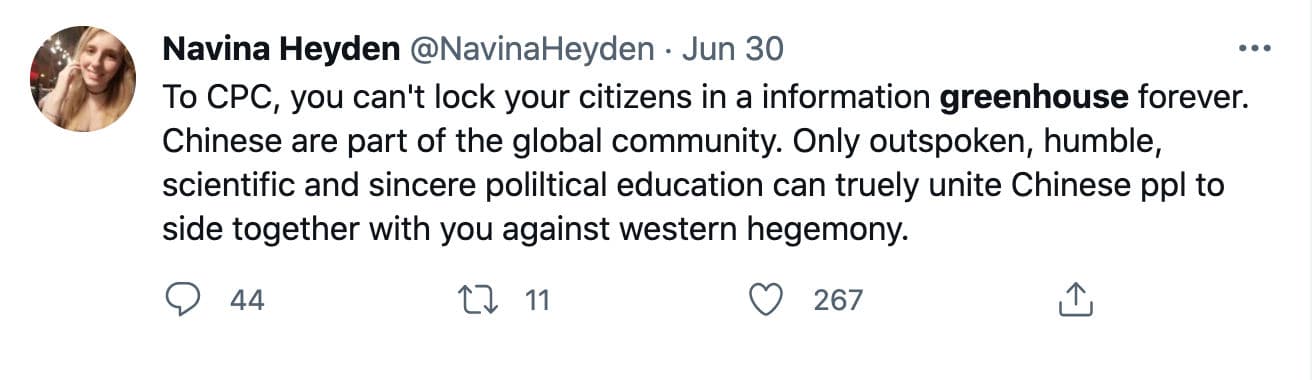

On Twitter, she wrote: “To CPC, you can’t lock your citizens in an information greenhouse forever.”

Sharing some of her frustrations regarding the Chinese social media sphere on Weibo, where she even admitted to missing Twitter, some Weibo users offered their support: “We’re on your side.”

By Manya Koetse (@manyapan)

With contributions by Miranda Barnes

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2021 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Media

12-Year-Old Girl from Shandong Gets Infected with HPV: Viral Case Exposes Failures in Protecting Minors

A doctor in Tai’an faced resistance when she tried to report a 12-year-old girl’s HPV case. She then turned to social media instead.

Published

3 months agoon

December 18, 2024

A 12-year-old girl from Shandong was diagnosed with HPV at a local hospital. When a doctor attempted to report the case, she faced resistance. Weibo users are now criticizing how the incident was handled.

Over the past week, there has been significant uproar on Chinese social media regarding how authorities, official channels, and state media in China have handled cases of sexual abuse and rape involving female victims and male perpetrators, often portraying the perpetrators in a way that appears to diminish their culpability.

One earlier case, which we covered here, involved a mentally ill female MA graduate from Shanxi who had been missing for over 13 years. She was eventually found living in the home of a man who had been sexually exploiting her, resulting in at least two children. The initial police report described the situation as the woman being “taken in” or “sheltered” by the man, a phrasing that outraged many netizens for seemingly portraying the man as benevolent, despite his actions potentially constituting rape.

Adding to the outrage, it was later revealed that local authorities and villagers had been aware of the situation for years but failed to intervene or help the woman escape her circumstances.

Currently, another case trending online involves a 12-year-old girl from Tai’an, Shandong, who was admitted to the hospital in Xintai on December 12 after testing positive for HPV.

HPV stands for Human Papillomavirus, a common sexually transmitted infection that can infect both men and women. Over 80% of women experience HPV infection at least once in their lifetime. While most HPV infections clear naturally within two years, some high-risk HPV types can cause serious illness including cancer.

“How can you be sure she was sexually assaulted?”

The 12-year-old girl in question had initially sought treatment for pelvic inflammatory disease, but upon review, her doctor discovered that she had been previously treated for vaginitis six months earlier. During further discussions with the girl, the doctor learned she had been sexually active with a boy five years her senior and was no longer attending school.

Given that the age of consent in China is 14 years old, the doctor sought to report the case to authorities. However, this effort was reportedly met with resistance from the hospital’s medical department, where she was allegedly questioned: “How can you be sure she was sexually assaulted?”

When attempts to escalate the case to the women’s federation and health commission went unanswered, the doctor turned to a blogger she knew (@反射弧超长星人影九) for help in raising awareness.

The blogger shared the story on Weibo but failed to receive a response through private messages from the Tai’an Police. They then contacted a police-affiliated Weibo channel they were familiar with, which eventually succeeded in alerting the Shandong police, prompting the formation of an investigation team.

As a result, on December 16, the 17-year-old boy was arrested and is now facing legal criminal measures.

According to Morning News (@新闻晨报), the boy in question is the 17-year-old Li (李某某), who had been in contact with the girl through the internet since May of 2024 after which they reportedly “developed a romantic relationship” and had “sexual relations.”

Meanwhile, fearing for her job, the doctor reportedly convinced the blogger to delete or privatize the posts. The blogger was also contacted by the hospital, which had somehow obtained the blogger’s phone number, asking for the post to be taken down. Despite this, the case had already gone viral.

The blogger, meanwhile, expressed frustration after the case gained widespread media traction, accusing others of sharing it simply to generate traffic. They argued that once the police had intervened, their goal had been achieved.

But the case goes beyond this specific story alone, and sparked broader criticisms on Chinese social media. Netizens have pointed out systemic failures that did not protect the girl, including the child’s parents, her school, and the hospital’s medical department, all of whom appeared to have ignored or silenced the issue. As WeChat blogging account Xinwenge wrote: “They all tacitly colluded.”

Xinwenge also referenced another case from 2020 involving a minor in Dongguang, Liaoning, who was raped and subsequently underwent an abortion. After the girl’s mother reported the incident to the police, the procuratorate discovered that a hospital outpatient department had performed the abortion but failed to report it as required by law. The procuratorate notified the health bureau, which fined the hospital 20,000 yuan ($2745) and revoked the department’s license.

Didn’t the hospital in Tai’an also violate mandatory reporting requirements? Additionally, why did the school allow a 12-year-old girl to drop out of the compulsory education programme?

“This is not a “boyfriend” or a “romantic relationship.””

The media reporting surrounding this case also triggered anger, as it failed to accurately phrase the incident as involving a raped minor, instead describing it as a girl having ‘sexual relations’ with a much older ‘boyfriend.’

Under Chinese law, engaging in sexual activity with someone under 14, regardless of their perceived willingness, is considered statutory rape. A 12-year-old is legally unable to give consent to sexual activity.

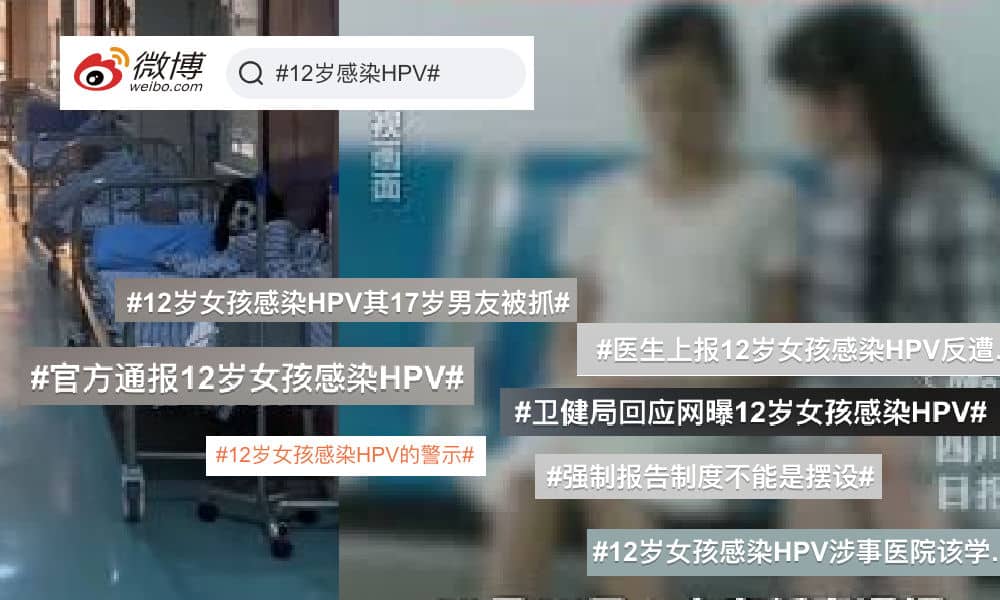

“The [Weibo] hashtag should not be “12-Year-Old Infected with HPV, 17-Year-Old Boyfriend Arrested” (#12岁女孩感染HPV其17岁男友被抓#); it should instead be “17-Year-Old Boy Sexually Assaulted 12-Year-Old, Causing Her to Become Infected” (#17岁男孩性侵12岁女孩致其感染#).”

Another blogger wrote: “First, we had the MA graduate from Shanxi who was forced into marriage and having kids, and it was called “being sheltered.” Now, we have a little girl from Shandong being raped and contracting HPV, and it was called “having a boyfriend.” A twelve-year-old is just a child, a sixth-grader in elementary school, who had been sexually active for over six months. This is not a “boyfriend” or a “romantic relationship.” The proper way to say it is that a 17-year-old male lured and raped a 12-year-old girl, infecting her with HPV.”

By now, the case has garnered widespread attention. The hashtag “12-Year-Old Infected with HPV, 17-Year-Old Boyfriend Arrested” (#12岁女孩感染HPV其17岁男友被抓#) has been viewed over 160 million times on Weibo, while the hashtag “Official Notification on 12-Year-Old Infected with HPV” (#官方通报12岁女孩感染hpv#) has received over 90 million clicks.

Besides the outrage over the individuals and institutions that tried to suppress the story, this incident has also sparked a broader discussion about the lack of adequate and timely sexual education for minors in Chinese schools. Liu Wenli (刘文利), an expert in children’s sexual education, argued on Weibo that both parents and schools play critical roles in teaching children about sex, their bodies, personal boundaries, and the risks of engaging with strangers online.

“Protecting children goes beyond shielding them from HPV infection,” Liu writes. “It means safeguarding them from all forms of harm. Sexual education is an essential part of this process, ensuring every child’s healthy and safe development.”

Many netizens discussing this case have expressed hope that the female doctor who brought the issue to light will not face repercussions or lose her job. They have praised her for exposing the incident and pursuing justice for the girl, alongside the efforts of those on Weibo who helped amplify the story.

The blogger who played a key role in exposing the story recently wrote: “I sure hope the authorities will give an award to the female doctor for reported this case in accordance with the law.” For some, the doctor is nothing short of a hero: “This doctor truly is my role model.”

By Manya Koetse, with contributions by Miranda Barnes

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Media

Hu Xijin’s Comeback to Weibo

After 90 days of silence, Hu Xijin is back on Weibo—but not everyone’s thrilled.

Published

4 months agoon

November 7, 2024

A SHORTER VERSION OF THIS ARTICLE WAS PART OF THE MOST RECENT WEIBO WATCH NEWSLETTER.

For nearly 100 days, since July 27, the well-known social and political commentator Hu Xijin (胡锡进) remained silent on Chinese social media. This was highly unusual for the columnist and former Global Times editor-in-chief, who typically posts multiple Weibo updates daily, along with regular updates on his X account and video commentaries. His Weibo account boasts over 24.8 million followers.

Various foreign media outlets speculated that his silence might be related to comments he previously made about the Third Plenum and Chinese economics, especially regarding China’s shift to treating public and private enterprises equally. But without any official statement, Chinese netizens were left to speculate about his whereabouts.

Most assumed he had, in some way, taken a “wrong” stance in his commentary on the economy and stock market, or perhaps on politically sensitive topics like the Suzhou stabbing of a Japanese student, which might have led to his being sidelined for a while. He certainly wouldn’t be the first prominent influencer or celebrity to disappear from social media and public view—when Alibaba’s Jack Ma seemed to have fallen out of favor with authorities, he went missing, sparking public concern.

After 90 days of absence, the most-searched phrases on Weibo tied to Hu Xijin’s name included:

胡锡进解封 “Hu Xijin ban lifted”

胡锡进微博解禁 “Hu Xijin’s Weibo account unblocked”

胡锡进禁言 “Hu Xijin silenced”

胡锡进跳楼 “Hu Xijin jumped off a building”

On October 31, Hu suddenly reappeared on Weibo with a post praising the newly opened Chaobai River Bridge, which connects Beijing to Dachang in Hebei—where Hu owns a home—significantly reducing travel time and making the more affordable Dachang area attractive to people from Beijing. The post received over 9,000 comments and 25,000 likes, with many welcoming back the old journalist. “You’re back!” and “Old Hu, I didn’t see you on Weibo for so long. Although I regularly curse your posts, I missed you,” were among the replies.

When Hu wrote about Trump’s win, the top comment read: “Old Trump is back, just like you!”

Not everyone, however, is thrilled to see Hu’s return. Blogger Bad Potato (@一个坏土豆) criticized Hu, claiming that with his frequent posts and shifting views, he likes to jump on trends and gauge public opinion—but is actually not very skilled at it, allegedly contributing to a toxic online environment.

Other bloggers have also taken issue with Hu’s tendency to contradict himself or backtrack on stances he takes in his posts.

Some have noted that while Hu has returned, his posts seem to lack “soul.” For instance, his recent two posts about Trump’s win were just one sentence each. Perhaps, now that his return is fresh, Hu is carefully treading the line on what to comment on—or not.

Nevertheless, a post he made on November 3rd sparked plenty of discussion. In it, Hu addressed the story of math ‘genius’ Jiang Ping (姜萍), the 17-year-old vocational school student who made it to the top 12 of the Alibaba Global Mathematics Competition earlier this year. As covered in our recent newsletter, the final results revealed that both Jiang and her teacher were disqualified for violating rules about collaborating with others.

In his post, Hu criticized the “Jiang Ping fever” (姜萍热) that had flooded social media following her initial qualification, as well as Jiang’s teacher Wang Runqiu (王润秋), who allegedly misled the underage Jiang into breaking the rules.

The post was somewhat controversial because Hu himself had previously stated that those who doubted Jiang’s sudden rise as a math talent and presumed her guilty of cheating were coming from a place of “darkness.” That post, from June 23 of this year, has since been deleted.

Despite the criticism, some appreciate Hu’s consistency in being inconsistent: “Hu Xijin remains the same Hu Xijin, always shifting with the tide.”

Hu has not directly addressed his absence from Weibo. Instead, he shared a photo of himself from 1978, when he joined the military. In that post, he reflected on his journey of growth, learning, and commitment to the country. Judging by his renewed frequency of posting, it seems he’s also recommitted to Weibo.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

What’s on Weibo Chapters

Subscribe

Five Trending Proposals at the Two Sessions 🔍

US-Russia Rapprochement and “Saint Zelensky”: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Shake-Up

“Li Jingjing Was Here”: Chinese Netizens React to Rumors of “Chinese Soldiers” in Russian Army

How Ne Zha 2’s Shen Gongbao Became Known as the Ultimate “Small-Town Swot”

Beyond the Box Office: What’s Behind Ne Zha 2’s Success?

Our Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Why Chinese Hit Movie “Her Story” is ‘Good Stuff’: Stirring Controversy and Celebrating Female Perspectives

Chiung Yao’s Suicide Farewell Letter: An English Translation

12-Year-Old Girl from Shandong Gets Infected with HPV: Viral Case Exposes Failures in Protecting Minors

Weibo Watch: Christmas in China Is Everywhere and Nowhere

Breaking the Taboo: China’s Sanitary Pad Controversy Sparks Demand for Change

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

Weibo Watch: China’s Online Feminism Is Everywhere

Story of Chinese Female MA Graduate Going Missing for 13 Years Sparks Online Storm

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight10 months ago

China Insight10 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music11 months ago

China Music11 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital9 months ago

China Digital9 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

-

China Arts & Entertainment10 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment10 months agoSinging Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments