China Insight

Critical Essay: “The Hype Surrounding Zibo BBQ is a Sign of Social Wasteland”

The essay suggests that the recent popularity of Zibo BBQ is a symptom of a society that’s all about consumerism and empty social spectacle.

Published

2 years agoon

Fast, fun, BBQ travel is a major topic on Chinese social media these days. One WeChat essay recently attracted attention for arguing that the hype surrounding Zibo barbecue is a symptom of a “sick society” in which people are disconnected from meaningful topics. While serious social issues are muted and superficial marketing tricks are blasted all over the internet, China’s “hypocritical youth” actively participate in the societal emptiness they say they reject.

Everyone is talking about Zibo. The old industrial city in Shandong suddenly became the hottest city in China earlier this year when big groups of young people hopped on trains to seize the post-Covid travel opportunity and enjoy a BBQ-filled weekend.

As described in our previous article on Zibo, the town achieved hit status through a combination of factors: its appealing local barbecue culture, the city’s hospitality to students in difficult zero Covid times, the 2023 spring travel craze, smart city marketing, and the social media trends surrounding Zibo which further fueled the hype.

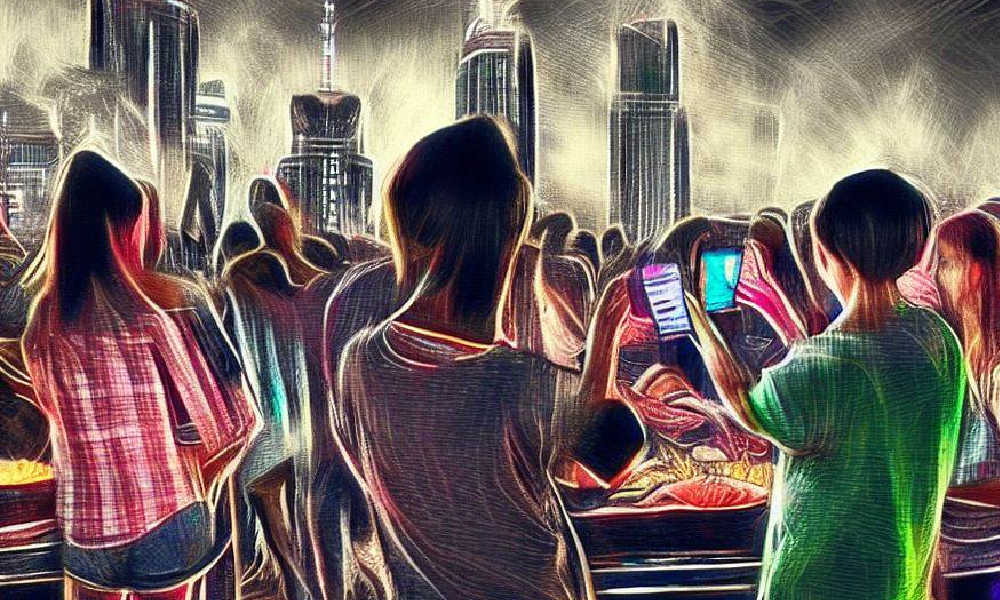

The Zibo BBQ craze. Image via 163.com.

Ever since April and throughout this Labor Day holiday, Zibo managed to crawl into Chinese social media’s top trending lists on a daily basis. And now Zibo has also become part of a bigger travel trend by Chinese younger generations that is all about fast, frugal fun (read here).

But despite all the videos showing BBQ parties, travel excitement, and smiling visitors, the Zibo hype is not all about roses, and there are also voices criticizing the craze.

One of these voices is that of the author of a recent article titled “The Hype Surrounding Zibo BBQ is a Sign of Social Wasteland” (“淄博烧烤走红是社会荒芜的表现”), which was posted by Chinese Professor of Journalism and Communication Liu Yadong (刘亚东).

Liu Yadong is a senior journalist and former editor-in-chief of Science and Technology Daily (科技日报). He is now a professor at Nankai University and the Dean of School of Journalism and Communication.

Although the article is attributed to Liu in most Weibo discussions, the article originally appeared on the WeChat account Jiuwenpinglun (旧闻评论), authored by ‘Picture-Taking Master Song’ (照相的宋师傅), pen name of prominent Chinese journalist Song Zhibiao (宋志标).

The article includes some hot takes on China’s recently hyped Zibo travel culture, which is strongly connected to social media governance and city marketing initiatives. The aurthor argues that the Zibo craze is a symbol of “societal illness” that uses temporary hypes, facilitated by social media, to cover up existing problems and, most of all, is a sign of a society that is devoid of true value.

It also criticizes those netizens/young people that jump in on the hype. Despite claiming to go against various top-down policies, they willingly and collectively are driving the hypes that are supposedly also part of dynamics that are strategically used by those in power to maintain influence.

Here, we provide a full translation of the short essay, translated by What’s on Weibo. Some parts are loosely translated or slightly edited for clarity, the Chinese original is included for your reference.

“The Hype Surrounding Zibo BBQ is a Sign of Social Wasteland” [TRANSLATION]

“Zibo barbecue has gone viral overnight, and with giant steps, we’re seeing a preposterous scene unfold: crowds of people are flocking to Zibo, long lines are forming in front of the BBQ stalls, the municipal government is making emergency preparations in various ways to facilitate “two-way travel” for young people coming to the city. This immersive scene is unfolding at the barbecue grills, while we are seeing Zibo’s ‘northeasternisation’ (东北化)* and the accelerated desolation of society. *[‘Dongbei-ization’ or ‘northeasterisation’ is a term used to refer to the phenomenon where people are leaving the northeastern provinces of China and moving to other provinces or regions which are then ‘northeasternized.’]

This desolation of society does not refer to a lack of people or empty streets. On the contrary, the contemporary social wasteland is crowded, grimy, and lively. The youth, in particular, are unconsciously marching in the same direction, and with fervor, they are chewing on Zibo BBQ ‘soul food’ as if they were devouring their own souls. In this existence, we are witnessing the demise of certain parts of themselves and our own.

Many people really want to explore the reasons why Zibo became such a hype, and they can list various factors, but they all stay at the instrumental level and do not go beyond it. This kind of result of up-and-down marketing of [China’s] cultural tourism industry is not so much because of collusion between local officials and traffic-generating mechanisms, as it is a random and hollow expression of society’s desolation. Society is sick, and the hyping of things like barbecue is just a symptom of that.”

淄博烧烤一夜走红,正在大踏步铺陈一副荒诞景象:成群结队的外地人蜂拥前往,烧烤摊前排满长队,市政府正在从各个方面应急建设,以奠基淄博与年轻人的“双向奔赴”。这是发生在烧烤架边上的沉浸式场景,淄博东北化,而社会加速荒芜化。

这里的社会荒芜并不是指人流量稀少,或街面荒凉,相反,现在的社会荒芜群集、油腻且热闹,尤其是年轻的躯壳无意识地追求整齐划一的动作,以饱满的热情,像吞噬自己灵魂一样咀嚼淄博烧烤的“灵魂三件套”。这样的存在,见证了自己和他人某些部分的死亡。

有人很想探究淄博烧烤走红的成因,罗列各种因素,但都停留在工具的层面,而没有往前更推进一步。这种文旅行业乍起乍落的营销成果,与其说是主政者与流量制造机制的合谋,莫若说是社会荒芜化随机的、空洞的表现。社会病了,烧烤等走红是它的症状。”

“It’s especially the young people that are unconsciously moving in the same direction and, full of enthusiasm, they are chewing on Zibo BBQ ‘soul food’ as if they were devouring their own souls.”

“Pulling stunts like turning barbecue into an online sensation and tourism bureau directors dressing up etc., help places to be covered by a huge filter, and it enables local authorities’ supervisory departments to shift their cultural and creative thinking to the short video era. One of the characteristics of the short video era is the shrewd operation that appears to conform to the lifestyle of the lower classes, grabbing their attention and using large-scale deception to cover up the rapid social barrenness of everyday life.

In this everyday life, a large number of more valuable topics are first decoupled from power, and then detached from the people closely related to them. In this process, these meaningful topics receive blows from two directions: firstly they are restrained and smeared by authorities, and then they are ridiculed and abandoned by the public. The erosion of our basis of values is similar to the process of desertification, and it is achieved through manipulation and conformation.

It seems that we can’t regard the people in this social wasteland purely as tools. They happily laugh in front of the barbecue stalls, they skillfully jumble up words and use special characters on social media to be influenced and influence others. For a moment, they forget about the ubiquitous risk of unemployment, and without a sense of history or awareness of problems, they fantasize about the next paradise.

The satirical thing is that while the young generation prides itself in ‘lying flat’ and in rejecting the policy lines [that encourage them] to have more kids, struggle, buy houses, etc, they vigorously participate in a movement to create a landscape of social desolation. The social wasteland provides them with a life kit where one thing after the next comes dashing up and then speeds away. This makes the wastage of the hypocritical youth especially evident, and because they are overly exploited, they are particularly ill.”

“烧烤网红、文旅局长便装等把戏,让一个地方罩上巨大的滤镜,帮助当局的主管部门从文创思维过渡到视频时代。短视频时代的特征之一,就是以名义上附和底层生活方式的精明操作,收割底层的注意力,以规模化的欺骗掩盖社会急速荒芜的日常。

在这种社会日常中,大量更有价值的议题先是与权力脱钩,再与和议题密切相关的人群脱钩。脱钩过程,价值议题遭到了两个方向的捶打:先是被权力遏制与污化,然后再受到民众的嘲笑与抛弃。价值基础的流失近似荒漠化进程,在操作与附和中达致。

似乎还不能将荒芜社会中人视作完全的工具人,他们在烧烤摊前发出快乐的笑声,他们娴熟地使用掺杂字母、异形字的话术在社交媒体上接承接灌输并灌输别人。一时间,他们忘了四面楚歌的失业风险,没有历史感与问题意识,却在畅想下一个乐园。

讽刺的是,年轻世代一边以躺平自诩,排斥多生、奋斗、买房等政策口径,另一边却精力旺盛地参与社会荒芜化的造景运动。社会荒芜提供了一个个飞奔而来又疾驰而去的生活套件,这让虚伪的年轻人损耗尤其明显,也因为被过度地利用,他们病得特别厉害。

“The people in this social wasteland aren’t just tools as they happily laugh in front of the barbecue stalls. For a moment, they forget about the risk of unemployment, and without a sense of history or awareness of problems, they fantasize about the next paradise.”

“The short video and click-through economy originated on the internet, and with the aid of the social wasteland, they have given birth to plastic flower-like gardens. The official attitude is very straightforward. On the one hand, they tame the flow of serious topics, directing and filtering their moral assessment; and on the other hand, they utilize it [the short video & click-through economy] to their advantage, harnessing the power of traffic to soften underlying anxieties.

Recently, cultural tourism chiefs in all parts of the country, according to the symbols of their local culture, competed with each other in [online] costume shows put together due to safe traffic flows.* These costume shows, realized for the sake of clicks, ended up straight in the social corner of topics such as the Zibo BBQ stalls – because there are no social topics to compete with, – and similarly resonated with spirit-lacking audiences. *[for more information on this trend, see our article about the cultural tourism chief video hype here.]

The “Zibo BBQ hype” and the trend of “cultural tourism chiefs costume” may appear as noteworthy accomplishments for cultural tourism bureaus, but the growth of such “light industry” is insufficient in addressing real issues, let alone the ongoing financial crisis affecting different regions. It is ineffectual in resolving the predicaments of economic development. While it is hailed in a desolate society, it may only serve as a temporary distraction, numbing the senses and blinding people from reality.

In the process of society becoming more desolate, the concept of “yān huǒ qì” (烟火气)* is almost destined to be emphasized, and it carries a feeling of nationalism and forlorn. Its visual effect is quite impressive, providing the illusion for both young and old in a desolate society, while dulling the strict street order enforced by the city police, giving people a feeling of intoxication. With the twinkling of the neon lights and the smoke filling up the air, the world can be anything.

*[Yān huǒ qì is a 2022 buzzword, initially means the smoke and fire produced from cooking food, but after ‘zero Covid,’ the phrase has come to be used to capture how restaurants and the hospitality sector across China seeing vitality again.]

Not long ago, ‘yān huǒ qì’ was a rhetoric to decorate the facade of the controlled economy, but now its existence has become like a common understanding between the government and the people. This rhetorical resonance, recited from above and echoed from below, has unexpectedly masked the perspective the term ‘yān huǒ qì’ represents, [namely that of] those in power overseeing it.”

“短视频及流量经济是局域网的原创,它们借助社会荒芜衍生出塑料花一样的花园。官方的取态非常干脆,它一方面驯化严肃议题的流量呈现,引导阻击它的道德评价;另一方面,它又滥用“为我所用”的原则攫取流量利益,以柔化深层次的焦虑。

前段时间,各地文旅局长按照当地的标志性文化,竞相登上由到安全流量组装而成的变装秀场。这些冲着流量变现而去的变装秀,因为没有与之竞的争社会议题,它们长驱直入到类似“淄博烧烤摊”的社会角落,与精神贫乏的受众同频共振。

“淄博烧烤走红”,“文旅局长变装”也许可作为文旅局的业绩,但这种“轻工业”的繁荣无法求解真问题,丝毫不减席卷各地的财政危机,更无助于解决经济发展的困境。当然,它们在荒芜社会空间搞出几声官民合唱,兴许可以暂时麻醉神经,遮断望眼。

在社会荒芜化的进程中,“烟火气”这个词得以强调几乎是命中注定,带着某种民族性与悲凉感。它的视觉效果相当可观,为荒芜社会提供了老少皆宜的幻觉,同时钝化了城管严控的街头秩序,令人们获得醉酒般的感受,假如霓虹闪烁,缭绕烟雾,亦可人间万象。

在不久之前,“烟火气”还是装点管控经济门面的修辞,现如今成为官民共识一样的存在。这种上有念叨、下有回声的修辞共鸣,出人意料地掩盖了“烟火气”这个词所象征的权力俯瞰视角,社会的荒芜化不仅蚕食价值议题,也以不知畏惧的憨态吞噬阶级差异。

“Have you considered that the desolation of society does not necessarily make it safer? In fact, it may just be another extreme form of a risky society. It is only ignored because the script of click-through traffic plays around the clock.”

“Similar to the intensity of a desert storm, the attention span of a desolate society is also brief, and the pace of the attention economy is fast. In a desolate society, the density of life for its members is low, and they can bear with or ignore their quality of life, but they cannot endure a short-lived infatuation. As the Zibo barbecue hype gained momentum, the countdown to the conclusion of the Ding Zhen craze* had already commenced. *[read about the hype surrounding Ding Zhen here.]

Some people believe that eliminating social diversity will also eliminate certain unpopular hidden dangers. However, have you considered that the desolation of society does not necessarily make it safer? In fact, it may just be another extreme form of a risky society that is ignored because the script of click-through traffic keeps playing around the clock. While you can control the click-through traffic, the logic of a decaying society remains uncontrollable.

Ultimately, the Zibo barbecue hype is very boring. It offers little solace to the government’s concerns about development or the public’s pressures for survival, unless we define a drunken and reckless lifestyle as positive. While we cannot fully blame the click-through economy for the desolation of society, it does contribute to numbing society’s awareness of how it operates, and the warning signs of a hollow society are all around us”.

“就像沙漠上的风暴特别强,荒芜社会的注意力也相当有限,注意力经济快速来也会快速去,毕竟荒芜意味着社会成员的生活密度低,他们可以容忍或漠视生活质量,但无法容忍略微时长的钟情。就在淄博烧烤走红的同时,始乱终弃的丁真式命结局就开始倒计时。

有人以为,消除了社会的多元化,就可以消除某些不受待见的隐患。何曾想,社会的荒芜化并不与安全社会划等号,它是风险社会的极端形式之一,只因日夜不停上演的流量剧本被忽视了。流量或许可以驯服,但社会荒芜化却沿着它的逻辑如脱缰之马。

说到底,淄博烧烤走红是非常无聊的事,它既不能真正安慰官方的发展焦虑,也无法减轻大众的生存压力,除非醉生梦死也被定义为积极的生活方式。当然,流量无法为社会的荒芜化负上全部责任,但它在合谋中钝化社会敏感度也是事实,荒芜将警讯紧紧包裹。”

Online Responses

The short essay is a critique of China’s youth, the online media sphere, and the click culture that goes from one hype to the next. But it is also a serious critique of Chinese authorities and the dynamics in place to mute serious social issues while blasting superficial trends.

The author suggests that everything is becoming less diverse (places like Zibo are ‘northeasternized’) and that society is actually so empty that people are constantly trying to fill the holes of their attention with the next meaningless buzz. Besides Zibo BBQ (link), he also mentions the Cultural Tourism chief cosplay trend (link), and the sudden rise to fame of Ding Zhen (link).

With Zibo and other domestic travel destinations being such a hot topic on Chinese social media recently, Liu’s critical essay – published on WeChat account Jiuwen Pinglun 旧闻评论 on April 17 – has inevitably become a topic of discussion.

By now, the essay has been deleted from Weixin, but online screenshots are still circulating online and have triggered new discussions this Labor Day holiday week (this link and this ifeng link are also still active). Various Weibo threads on the essay received hundreds of likes and comments over the past two days.

Some bloggers on Weibo value Liu’s perspective. As one blogger (@校长梁山) writes: “This is a thoughtful and high-quality article that you rarely come across (..) I have no intention of criticizing the government, but in terms of social management, the views in this article are worth thinking about.”

“Actually, he is right,” another commenter writes: “What he’s expressing is that the current economic downfall cannot be solved by the next barbecue hype, but this is something the media is burying” (the idiom used is yǎn ěr dào líng 掩耳盗铃, meaning covering one’s ears while stealing a bell, burying one’s head in the sand).” Those agreeing with the author suggest that Zibo’s success might be a win for its local cultural tourism department, but actually says nothing about a recovery of other industries and economy at large.

But there are also those who think Liu’s perspective is outdated and that, while talking about a lack of meaning, his own words are actually meaningless: “I have no idea what he is talking about.”

Zibo crowds, image via 163.com.

Some say he is making a big fuss over nothing, suggesting that it is only normal for people to want to seek for entertainment and simple pleasures like eating BBQ skwers, and that it does not represent a bigger problem at all. He is “moaning over an imaginary illness,” one Weibo user wrote (“wú bìng shēn yín” 无病呻吟).

Content deleted on WeChat.

Although not everyone agrees with Liu’s takes, many do agree that it gives food for thought. However, the deletion of the essay itself and the removal of some related online comment threads also prevents further discussions on the topic, which ironically exemplifies one of the issues that the author aimed to address in his essay.

By Manya Koetse

Edited May 19, 2023: An earlier version of this article suggested Liu Yadong (刘亚东) is the original author of the critical essay. Although the article is attributed to Liu on Chinese social media, Liu reposted it and had his own bio under the article, but the original (censored) article is authored by Song Zhibao (宋志标).

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Insight

From Trade Crisis to Patriotic Push: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Tariffs

“This moment is the time to reflect on our unity. If we can choose domestic alternatives, we should.”

Published

3 days agoon

April 5, 2025

“China’s countermeasures are here” (#中方反制措施来了#). This hashtag, launched by Party newspaper People’s Daily, went top trending on Chinese social media on Friday, April 4, after President Trump announced steep new tariffs on Wednesday, including a universal 10 percent “minimum base tariff” on all imported goods and especially targeting China with an additional 34% reciprocal tariff as part of so-called “liberation day.”

Countermeasures were announced on Friday. China’s State Council Customs Tariff Commission Office (国务院关税税则委员会办公室) issued an announcement stating that, starting from April 10, an additional 34% tariff will be levied on all imported goods originating from the United States, on top of existing tariff rates.

Other countermeasures include immediate export restrictions on seven key medium to heavy rare earth elements, which are important for manufacturing critical products used in semiconductors, defense, aerospace, and green energy.

“This won’t make America great again”

The official response to the tariffs, both from state media and the government, has been twofold: on the one hand, it criticizes the U.S. for placing American interests above the good of the global community, arguing that the move only hurts the U.S., its people, and the world. On the other hand, the Chinese side stresses that although they do not believe tariff wars are the answer, China is not afraid of a trade war and will not sit idly by, but will respond with equal measures.

Chinese official media have condemned the new tariffs, which led to the largest single-day market drop in years. Describing the reactions of various experts, Xinhua News highlighted a comment by a Croatian professor, stating that the policy will only increase export prices and worsen inflation, ultimately hurting middle- and working-class Americans — and noting that the policy “won’t make America great again” (不会“让美国再次伟大”).

The official announcement by Chinese state media regarding China’s countermeasures received widespread support in its (highly controlled) comment sections, with both media outlets and netizens echoing the message that China will not be bullied by the U.S.

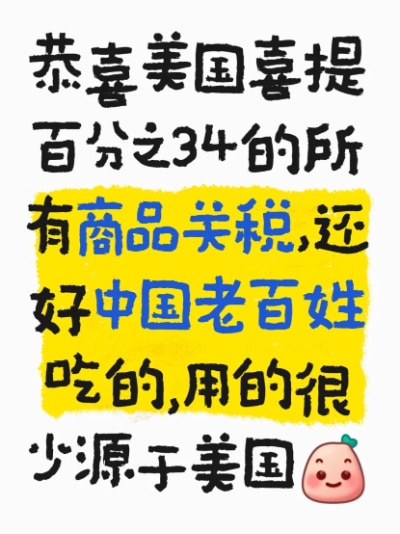

On Xiaohongshu, similar sentiments shnone through in popular posts, such as one person writing:

💬 “Congratulations to the U.S. on receiving a 34% tariff on all its goods! Luckily, very few of the things ordinary Chinese people eat or use come from the U.S. anyway.

#RMB purchasing power #China will inevitably be unified #Consumer confidence #Contemporary Chinese economy #Carrying forward the construction of a Beautiful China”

“Monday’s stock market will be a bloodbath,” another commenter wrote.

One Weibo blogger (@兰启昌) saw the recent developments as another sign of an ongoing trend of “de-globalization” (逆全球化).

But beyond global economics and geopolitics, many Chinese netizens — from Weibo to Xiaohongshu — seem more focused on how the new policies will affect everyday consumers.

Netizens have been actively discussing which goods will be hit hardest by the new tariffs. Based on 2023 trade data, here’s a breakdown of the top exports between China and the United States — and the sectors most likely to feel the impact.

🔷🇺🇸🇨🇳Top 10 Chinese Exports to the U.S.

1. Electronics and Machinery

Includes smartphones, laptops, tablets, integrated circuits, and image processing equipment.

2. Furniture, Home Goods & Toys

Such as video game consoles, lamps, and much more.

3. Textiles and Apparel

Garments, footwear, and accessories like sunglasses.

4. Metals and Related Products

Especially steel and steel-based items.

5. Plastic and Rubber Products

Widely used in packaging, manufacturing, and consumer goods.

6. Transportation Equipment

Electric vehicles, passenger cars, motorcycles, scooters, and drones.

7. Low-Value Commodities

Bulk items used in general trade and low-cost manufacturing.

8. Chemicals

Industrial chemicals and related materials.

9. Medical and Optical Instruments

Includes medical devices and precision instruments.

10. Paper Products

Ranging from office supplies to industrial paper goods.

🔹🇨🇳🇺🇸Top 10 U.S. Exports to China

1. High-Tech Machinery and Electronics

Especially integrated circuits, turbine engine components, and semiconductor manufacturing equipment.

2. Energy Products

Crude oil, liquefied propane and butane, natural gas, and coking coal.

3. Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals

Includes cosmetics, cleaning agents, and various medical drugs.

4. Soybeans

A key agricultural export widely used in food and animal feed in China.

5. Transportation Equipment

Such as automobiles and aircraft parts.

6. Medical and Optical Devices

Medical precision equipment, diagnostic tools, and lab instruments.

7. Plastic and Rubber Goods

Used in both consumer and industrial sectors.

8. Metal Products

Primarily iron and steel exports.

9. Wood and Pulp Products

Lumber, wood pulp, charcoal, and paper goods.

10. Meat

Including beef, pork, and poultry.

Those doing trade with the US, or otherwise involved in made-in-China products, like those working clothing and furniture factories, will inevitably be affected by the tariffs.

“Patriotism isn’t just a sentiment – it’s an action”

Much of the popular online conversation has focused on concrete examples of what kinds of things might get more expensive for Chinese consumers in their everyday lives.

Some bloggers noted that people might start to see price hikes in everyday groceries like dairy, meat, corn, and soybeans. With fewer soybeans coming in from the US, cooking oil prices may also rise.

China is the world’s largest consumer of soybeans, but because domestic production is relatively low, soybeans remain a key import.

Then there are popular American brands in the Chinese market that are expected to get pricier too — like beauty and health products, Starbucks coffee, or Häagen-Dazs ice cream.

Some also predicted a 30% to 40% increase in prices for iPhones and other Apple products.

Contrary to the earlier comment by the Xiaohongshu blogger, some netizens explain just how many American products are actually used by Chinese consumers, with many American companies operating in China — from McDonald’s and Coca-Cola, Walmart to Disney or Warner Brothers, Procter & Gamble to Colgate and Estée Lauder.

What’s noteworthy in these discussions, however, is a strong tendency to point to Chinese alternatives and encourage smart buying instead of following hypes (“理性替代,拒绝跟风”): No need to panic about soybeans — there are domestic alternatives, and China’s own soybean program is getting a boost. Who needs Starbucks when there’s Luckin Coffee? Why buy an iPhone when you can get a Huawei? Skip the Tesla, go for a BYD.

In these discussions, the ‘crisis’ is turned into an ‘opportunity’ for Chinese companies to focus even more on the Chinese market, and for Chinese consumers to, more than ever, actively embrace and celebrate local brands and made-in-China products.

One Chinese blogger (@O浅夏拾光O) wrote:

💬 “This moment is the time to reflect on our unity. If we can choose domestic alternatives, we should. For example, we can use rapeseed oil or peanut oil instead of imported soybean oil; we can buy cost-effective Chinese electronics instead of foreign brands. Support domestic products and respond to the nation’s call to expand domestic consumption.

We must have faith in our country. Only by uniting as one, young and old all together, the entire country working together, can we withstand all hazards. As Professor Ai Yuejin (艾跃进) once said, patriotism isn’t just a sentiment – it’s an action. As long as our core is stable and we are united in spirit, no hardship can defeat us.”

Despite the major happenings and the big words, some people just care about the small things: “As long as KFC and McDonald’s don’t raise their prices, it’s all fine by me.”

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Insight

Squat or Sit? China’s Great Toilet Debate and the Problem of Footprints on the Seat

From squatting to standing on seats: the messy reality of sitting toilets in Beijing malls.

Published

2 weeks agoon

March 25, 2025

FROM THE WEIBO WATCH PREMIUM NEWSLETTER

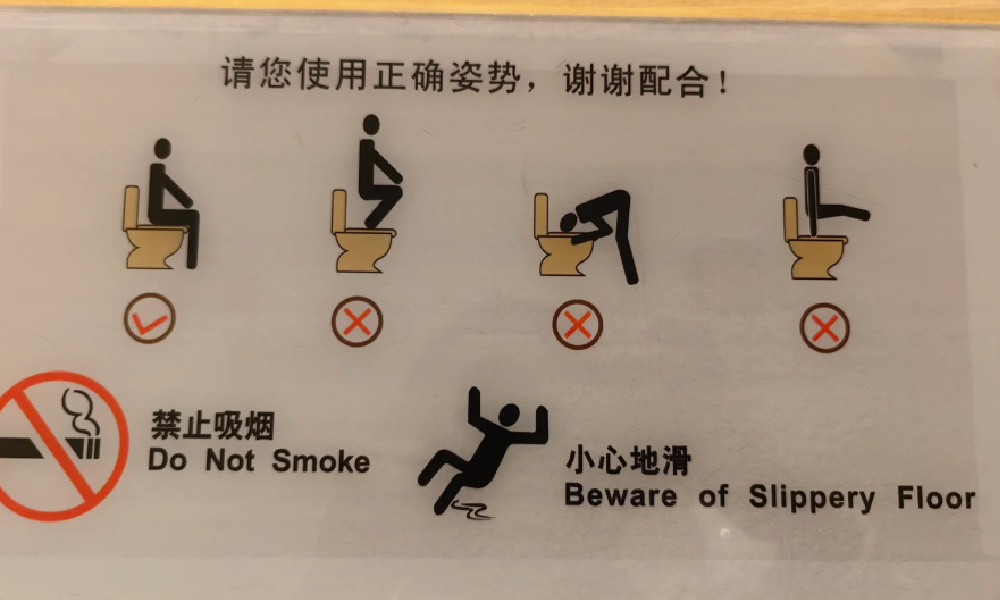

Shoe prints on top of the toilet seat are never a pretty sight. To prevent people from squatting over Western-style sitting toilets, there are some places that will place stickers above the toilet, reminding people that standing on the seat is strictly forbidden.

For years, this problem has sparked debate. Initially, these discussions would mostly take place outside of China, in places with a large number of Chinese tourists. In Switzerland, for example, the famous Rigi Railways caused controversy for introducing separate trains with special signs explaining to tourists, especially from China, how (not) to use the toilet.

Squat toilets are common across public areas in China, especially in rural regions, for a mix of historical, cultural, and practical reasons. There is also a long-held belief — backed by studies (like here or here) — that the squatting position is healthier for bowel movements (for more about the history of squat toilets in China, see Sixth Tone’s insightful article here).

Public squatting toilets in Beijing, images via Xiaohongshu.

Without access to the ground-level squat toilets they are used to — and feel more comfortable with — some people will climb on top of sitting toilets to use them in the way they’re accustomed to, seeing squatting as the more natural and hygienic method.

Not only does this make the toilet seat all messy and muddy, it is also quite a dangerous stunt to pull, can break the toilet, and lead to pee and poo going into all kinds of unintended directions. Quite shitty.

Squatting on toilets makes the seat dirty and can even break the toilet.

Along with the rapid modernization of Chinese public facilities and the country’s “Toilet Revolution” over the past decade, sitting toilets have become more common in urban areas, and thus the sitting-toilet-used-as-squat-toilet problem is increasingly becoming topic of public debate within China.

The Toilet Committee and Preference for Sitting Toilets

Is China slowly shifting to sitting toilets? Especially in modern malls in cities like Beijing, or even at airports, you see an increasing number of Western-style sitting toilets (坐厕) rather than squatting toilets (蹲厕).

This shift is due to several factors:

🚽📌 First, one major reason for the rise in sitting toilets in Chinese public places is to accommodate (foreign) tourists.

In 2015, China Daily reported that one of the most common complaints among international visitors was the poor condition of public toilets — a serious issue considering tourists are estimated to use public restrooms over 27 billion times per year.

That same year, China’s so-called “Toilet Revolution” (厕所革命) began gaining momentum. While not a centralized campaign, it marked a nationwide push to upgrade toilets across the country and improve sanitation systems to make them cleaner, safer, and more modern.

This movement was largely led by the tourism sector, with the needs of both domestic and international travelers in mind. These efforts, and the buzzword “Toilet Revolution,” especially gained attention when Xi Jinping publicly endorsed the campaign and connected it to promoting civilized tourism.

In that sense, China’s toilet revolution is also a “tourism toilet revolution” (旅游厕所革命), part of improving not just hygiene, but the national image presented to the world (Cheng et al. 2018; Li 2015).

🚽📌 Second, the growing number of sitting toilets in malls and other (semi)public spaces in Beijing relates to the idea that Western-style toilets are more sanitary.

Although various studies comparing the benefits of squatting and sitting toilets show mixed outcomes, sitting toilets — especially in shared restrooms — are generally considered more hygienic as they release fewer airborne germs after flushing and reduce the risk of infection (Ali 2022).

There are additional reasons why sitting toilets are favored in new toilet designs. According to Liang Ji (梁骥), vice-secretary of the Toilet Committee of the China Urban Environmental Sanitation Association (中国城市环境卫生协会厕所专业委员会), sitting toilets are also increasingly being introduced in public spaces due to practical concerns.

🚽📌 Squatting is not always easy, and can pose a safety risk, particularly for the elderly, pregnant women, and people with disabilities.

🚽📌 Then there are economic reasons: building squat toilets in malls (or elsewhere) requires a deeper floor design due to the sunken space needed below the fixture, which increases both construction time and cost.

🚽📌 Liang also points to an aesthetic factor: sitting toilets simply look more “high-end” and are easier to clean, which is why many consumer-oriented spaces prefer to install Western-style toilets.

So although there are plenty of reasons why sitting toilets are becoming a norm in newly built public spaces and trendy malls, they also lead to footprints on toilet seats — and all the problems that come with it.

The Catch 22 of Sitting vs Squad Toilets

This week, the issue became a trending topic on Weibo after Beijing News published an investigative report on it. The report suggested that most shopping malls in Beijing now have restrooms with sitting toilets, which should, in theory, be cleaner than the squat toilets of the past — but in reality, they’re often dirtier because people stand on them. This issue is more common in women’s restrooms, as men’s restrooms typically include urinals.

In researching the issue, a reporter visited several Beijing malls. In one women’s restroom, the reporter observed 23 people entering within five minutes. Although the restroom had only three squat toilets versus seven sitting ones, around 70% of the users opted for the squat toilets.

Upon inspection, most of the seven sitting toilets were dirty — despite being equipped with disposable seat covers — showing clear signs of urine stains and footprints. They found that sitting toilets being used as squat toilets is extremely common.

It’s a bit of a Catch-22. People generally prefer clean toilets, and there’s also a widespread preference for squat toilets. This leads to sitting toilets being used as squat toilets, which makes them dirty — reinforcing the preference for squat toilets, since the sitting toilets, though meant to be cleaner, end up dirtier.

In interviews with 20 women, nearly 80% said they either hover in a squat or directly squat on the toilet seat. One woman said, “I won’t sit unless I absolutely have to.” While some of those quoted in the article said that sitting toilets are more comfortable, especially for elderly people, they are still not preferred when the seats are not clean.

In the Beijing News article, the Toilet Committee’s Liang Ji suggested that while a balanced ratio of squat and sitting toilets is necessary, a gradual shift toward sitting toilets is likely the future for public restrooms in China.

How NOT to use the sitting toilet. Sign photographed by Xiaohongshu user @FREAK.00.com.

Liang also highlighted the importance of correct toilet use and the need to consider public habits in toilet design.

In Squatting We Trust

On Chinese social media, however, the majority of commenters support squatting toilets. One popular comment said:

💬 “Please make all public toilets squat toilets, with just one sitting toilet reserved for people with disabilities.”

Squatting toilets in a public toilet in a Beijing hutong area, image by Xiaohongshu user @00后饭桶.

The preference for squatting, however, doesn’t always come down to bowel movements or tradition. Many cite a lack of trust in how others use public toilets:

💬 “When it comes to things for public use, it’s best to reduce touching them directly. Honestly, I don’t trust other people…”

💬 “Squatting is the most hygienic. At least I don’t have to worry about touching something others touched with their skin.”

💬 “I hate it when all the toilets in the women’s restroom at the mall are sitting toilets. I’m almost mastering the art of doing the martial-arts squat (蹲马步).”

Others view the gradual shift toward sitting toilets as a result of Westernization:

💬 “Sitting toilets are a product of widespread ‘Westernization’ back in the day — the further south you go, the worse it gets.”

But some come to the defense of sitting toilets:

💬 “Are there really still people who think squat toilets are cleaner? The chances of stepping in poop with squat toilets are way higher than with sitting ones. Sitting toilet seats can be wiped with disinfectant or covered with paper. Some people only care about keeping themselves ‘clean’ without thinking about whether the next person might end up stepping in their mess.”

💬 One reply bluntly said: “I don’t use sitting toilets. If that’s all there is, I’ll just squat on top of it. Not even gonna bother wiping it.”

It’s clear this debate is far from over, and the issue of people standing on toilet seats isn’t going away anytime soon. As China’s toilet revolution continues, various Toilet Committees across the country may need to rethink their strategies — especially if they continue leaning toward installing more sitting toilets in public spaces.

As always, Taobao has a solution. For just 50 RMB (~$6.70), you can order an anti-slip sitting-to-squatting toilet aid through the popular e-commerce platform.

The Taobao solution.

For Chinese malls, offering these might be cheaper than dealing with broken toilets and the never-ending battle against footprints on toilet seats…

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

References:

Ali, Wajid, Dong-zi An, Ya-fei Yang, Bei-bei Cui, Jia-xin Ma, Hao Zhu, Ming Li, Xiao-Jun Ai, and Cheng Yan. 2022. “Comparing Bioaerosol Emission after Flushing in Squat and Bidet Toilets: Quantitative Microbial Risk Assessment for Defecation and Hand Washing Postures.” Building and Environment 221: 109284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109284.

Bhattacharya, Sudip, Vijay Kumar Chattu, and Amarjeet Singh. 2019. “Health Promotion and Prevention of Bowel Disorders Through Toilet Designs: A Myth or Reality?” Journal of Education and Health Promotion 8 (40). https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_198_18.

Cao, Jingrui 曹晶瑞, and Tian Jiexiong 田杰雄. 2025. “城市微调查|商场女卫生间,坐厕为何频频变“蹲坑”? [In Shopping Mall Women’s Restrooms, Why Do Sitting Toilets Frequently Turn into ‘Squat Toilets’?]” Beijing News, March 20. https://weibo.com/ttarticle/p/show?id=2309405146044773302810. Accessed March 19, 2025.

Cheng, Shikun, Zifu Li, Sayed Mohammad Nazim Uddin, Heinz-Peter Mang, Xiaoqin Zhou, Jian Zhang, Lei Zheng, and Lingling Zhang. 2018. “Toilet Revolution in China.” Journal of Environmental Management 216: 347–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.09.043.

Dai, Wangyun. 2018. “Seats, Squats, and Leaves: A Brief History of Chinese Toilets.” Sixth Tone, January 13. https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1001550. Accessed March 22, 2025.

Li, Jinzao. 2015. “Toilet Revolution for Tourism Evolution.” China Daily, April 7. https://europe.chinadaily.com.cn/opinion/2015-04/07/content_20012249_2.htm. Accessed March 22, 2025.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

No Quiet Qingming: From High-Tech Tomb-Sweeping to IShowSpeed & the Seven China Streams

From Trade Crisis to Patriotic Push: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Tariffs

China Trending Week 14: Gucci Fake Lipstick, Xiaomi SU7 Crash, Yoon’s Impeachment

Strange Encounter During IShowSpeed’s Chengdu Livestream

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

Our Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Beyond the Box Office: What’s Behind Ne Zha 2’s Success?

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

15 Years of Weibo: The Evolution of China’s Social Media Giant

Tuning Into the Year of the Snake

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

TikTok Refugees, Xiaohongshu, and the Letters from Li Hua

The ‘China-chic Girl’ Image and the Realities of China’s Competitive Food Delivery Market

“Black Myth: Wukong”: From Gaming Screens to the CMG Spring Festival Gala?

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight11 months ago

China Insight11 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

-

China Arts & Entertainment11 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment11 months agoSinging Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng