China Digital

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

As American ‘TikTok Refugees’ flock to China’s Xiaohongshu (Rednote), their encounter with ‘Li Hua’ strikes a chord in divided times.

Published

2 months agoon

FROM THE WEIBO WATCH PREMIUM NEWSLETTER

China’s Xiaohongshu (Rednote) has seen an unprecedented influx of foreign “TikTok refugees” over the past week, giving rise to endless jokes. But behind this unexpected online migration lie some deeper themes—geopolitical tensions, a desire for cultural exchange, and the unexpected role of the fictional character Li Hua in bridging the divide.

Imagine you are Li Hua (李华), a Chinese senior high school student. You have a foreign friend, far away, in America. His name is John, and he has asked you for some insight into Chinese Spring Festival, for an upcoming essay has to write for the school newspaper. You need to write a reply to John, in which you explain more about the history of China’s New Year festival and the traditions surrounding its celebrations.

This is the kind of writing assignment many Chinese students have once encountered during their English writing exams in school during the Gaokao (高考), China’s National College Entrance Exams. The figure of ‘Li Hua’ has popped up on and off during these exams since at least 1995, when Li invited foreign friend ‘Peter’ to a picnic at Renmin Park.

Over the years, Li Hua has become somewhat of a cultural icon. A few months ago, Shangguan News (上观新闻) humorously speculated about his age, estimating that, since one exam mentioned his birth year as 1977, he should now be 47 years old—still a high school student, still helping foreign friends, and still introducing them to life in China.

Li Hua: the connector, the helper, the icon.

This week, however, Li Hua unexpectedly became a trending topic on social media—in a week that was already full of surprises.

With a TikTok ban looming in the US (delayed after briefly taking effect on Sunday), millions of American TikTok users began migrating to other platforms this month. The most notable one was the Chinese social media app Xiaohongshu (now also known as Rednote), which saw a massive influx of so-called “TikTok refugees” (Tiktok难民). The surge propelled Xiaohongshu to the #1 spot in app stores across the US and beyond.

This influx of some three million foreigners marked an unprecedented moment for a domestic Chinese app, and Xiaohongshu’s sudden international popularity has brought both challenges and beautiful moments. Beyond the geopolitical tension between the US and China, Chinese and American internet users spontaneously found common ground, creating unique connections and finding new friends.

While the TikTok/Xiaohongshu “honeymoon” may seem like just a humorous trend, it also reflects deeper, more complex themes.

✳️ National Security Threat or Anti-Chinese Witchhunt?

At its core, the “TikTok refugee” trend has sprung from geopolitical tensions, rivalry, and mutual distrust between the US and China.

TikTok is a wildly popular AI-powered short video app by Chinese company ByteDance, which also runs Douyin, the Chinese counterpart of the international TikTok app. TikTok has over 170 million users in the US alone.

A potential TikTok ban was first proposed in 2020, amid escalating US-China tensions. President Trump initiated the move, citing security and data concerns. In 2024, the debate resurfaced in global headlines when President Biden signed the “Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act,” giving ByteDance nine months to divest TikTok or face a US ban.

TikTok, however, has continuously insisted it is apolitical, does not accept political promotion, and has no political agenda. Its Singaporean CEO Shou Zi Chew maintains that ByteDance is a private business and “not an agent of China or any other country.”

🇺🇸 From Washington’s perspective, TikTok is viewed as a national and personal security threat. Officials fear the app could be used to spread propaganda or misinformation on behalf of the Chinese Communist Party.

🇨🇳 Beijing, meanwhile, criticizes the ban as an act of “bullying,” accusing the US of protectionism and attempting to undermine China’s most successful internet companies. They argue that the ban reflects America’s inability to compete with the success of Chinese digital products, labeling the scrutiny around TikTok as a “witch hunt.”

Political cartoon about the American “witchhunt” against TikTok, shared on Weibo in 2023, also published on Twitter by Lianhe Zaobao.

“This will eventually backfire on the US itself,” China’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin predicted in 2024.

Wang turned out to be quite right, in a way.

When it became clear in mid-January that the ban was likely to become a reality, American TikTok users grew increasingly frustrated and angry with their government. For many of these TikTok creators, the platform is not just a form of entertainment—it has become an essential part of their income. Some directly monetize their content through TikTok, while others use it to promote services or products, targeting audiences that other platforms like Facebook, Instagram, or X can no longer reach as effectively.

Initially, the mass migration of American users to Xiaohongshu was a symbolic protest against US policies. Users advocated for the right to choose their preferred social media, and voiced their frustration at how their favorite app had become a pawn in US-China geopolitical tensions. Rejecting the narrative that “data must be protected from the Chinese,” many pointed out that privacy concerns were equally valid for US-based platforms. As an act of playful political defiance, these users downloaded Xiaohongshu to demonstrate they didn’t fear the government’s warnings about Chinese data collection.

(If they had the option, by the way, they would have installed Douyin—the actual Chinese version of TikTok—but it is only available in Chinese app stores, whereas Xiaohongshu is accessible in international stores, so it was picked as ‘China’s version of TikTok.’)

Xiaohongshu is actually not the same as TikTok at all. Founded in 2013, Xiaohongshu (literal translation: Little Red Book) is a popular app with over 300 million users that combines lifestyle, travel, fashion, and cosmetics with e-commerce, user-generated content, and product reviews. Like TikTok, it offers personalized content recommendations and scrolling videos, but is otherwise different in types of engagement and being more text-based.

As a Chinese app primarily designed for a domestic audience, the sudden wave of foreign users caused significant disruption. Xiaohongshu must adhere to the guidelines of China’s Cyberspace Administration, which requires tight control over information flows. The unexpected influx of foreign users undoubtedly created challenges for the company, not only prompting them to implement translation tools but also recruiting English-speaking content moderators to manage the new streams of content. Foreigners addressing sensitive political issues soon found their accounts banned.

Of course, there is undeniable irony in Americans protesting government control by flocking to a Chinese app functioning within an internet system that is highly controlled by the government—a move that sparked quite some debate and criticism as well.

✳️ The Sino-American ‘Dear Li Hua’ Moment

While the initial hype around Xiaohongshu among TikTok users was political, the trend quickly shifted into a moment of cultural exchange. As American creators introduced themselves on the platform, Chinese users gave them a warm welcome, eager to practice their English and teach these foreign newcomers how to navigate the app.

Soon, discussions about language, culture, and societal differences between China and the US began to flourish. Before long, “TikTok refugees” and “Xiaohongshu natives” were collaborating on homework assignments, swapping recipes, and bonding through humor.

For instance, Chinese users jokingly asked the “TikTok refugees” to pay a “cat tax” for seeking refuge on their platform, which American users happily fulfilled by posting adorable cat photos. American users, in turn, joked about becoming best friends with their “Chinese spies,” playfully mocking their own government’s fears about Chinese data collection.

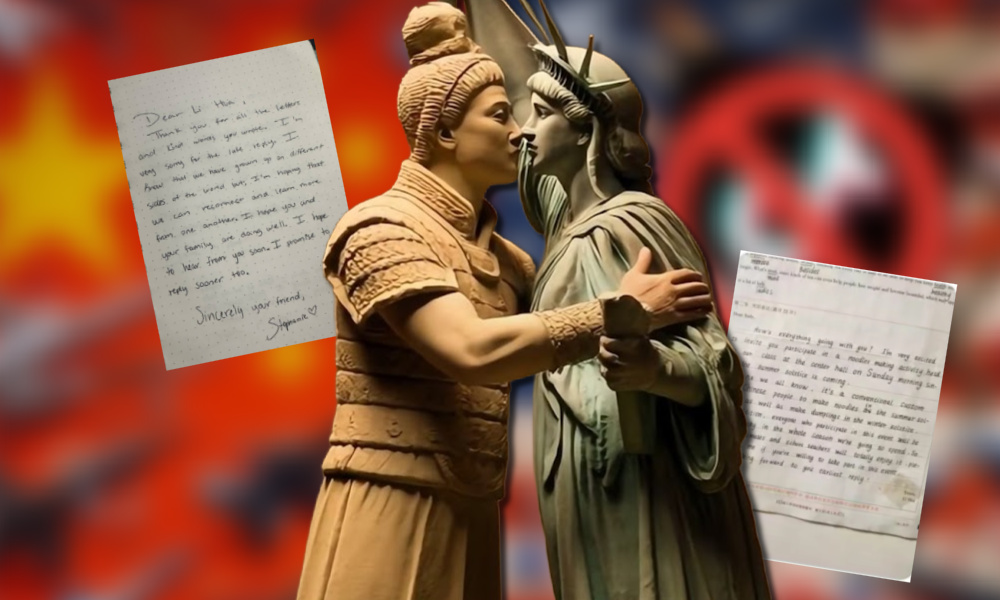

The newfound camaraderie sparked creativity, as users began generating humorous images celebrating the bond between American and Chinese netizens—like Ronald McDonald cooking with the Monkey King or the Terra Cotta Soldier embracing the Statue of Liberty. Later, some images even depicted the pair welcoming their first “baby.”

🇺🇸 At the same time, it became clear just how little Americans and Chinese truly know about each other. Many American users expressed surprise at the China they discovered through Xiaohongshu, which contrasted sharply with negative portrayals they’ve seen in the media. While some popular US narratives often paint Chinese citizens as “brainwashed” by their government, many TikTok users began to reflect on how their own perspectives had been shaped—or even “manipulated”—by their media and government.

🇨🇳 For Chinese users, the sudden interaction underscored their digital isolation. Over the past 15 years, China has developed its own tightly regulated digital ecosystem, with Western platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube inaccessible in the mainland. While this system offers political and economic advantages, it has left many young Chinese people culturally hungry for direct interaction with foreigners—especially after years of reduced exchange caused by the pandemic, trade tensions, and bilateral estrangement. (Today, only some 1,100 American students are reportedly studying in China.)

The enthusiasm and eagerness displayed by American and Chinese Xiaohongshu users this week actually underscores the vacuum in cultural exchange between the two nations.

As a result of the Xiaohongshu migration, language-learning platform Duolingo reported a 216% rise in new US users learning Mandarin—a clear sign of growing interest in bridging the US-China divide.

Mourning the lack of intercultural communication and celebrating this unexpected moment of connection, Xiaohongshu users began jokingly asking Americans if they had ever received their “Li Hua letters.”

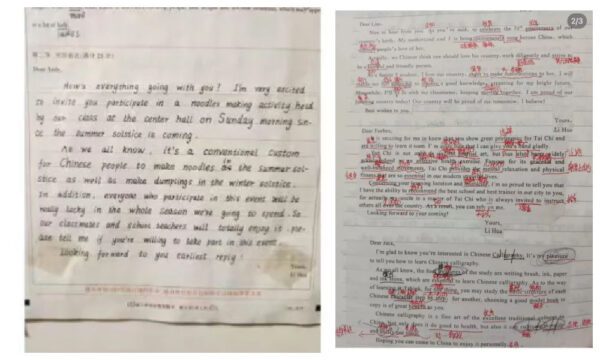

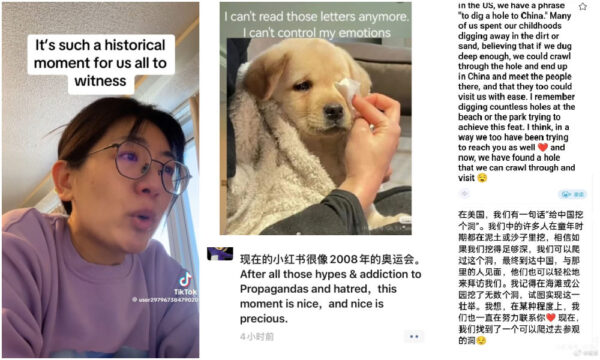

What started as some lighthearted remarks evolved into something much bigger as Chinese users dug up their old Gaokao exam papers and shared the letters they had written to their imaginary foreign friends years ago. These letters, often carefully stored in drawers or organizers, were posted with captions like, “Why didn’t you reply?” suggesting that Chinese students had been trying to reach out for years.

Example letters on Xiaohongshu: ‘Li Hua’ writing to foreign friends.

The story of ‘Li Hua’ and the replies he never received struck a chord with American Tiktok users. One user, Debrah.71, commented:

“It was the opposite for us in the USA. When I was in grade school, we did the same thing—we had foreign pen pals. But they did respond to our letters.”

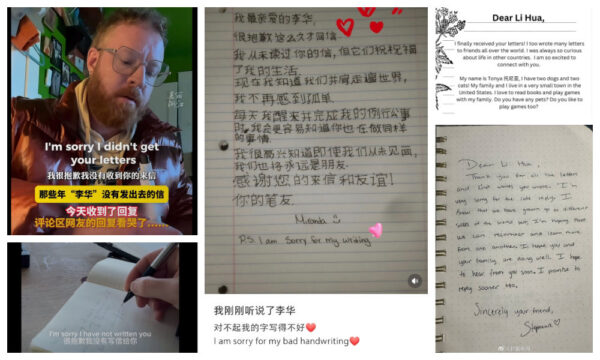

Then, something extraordinary happened: Americans started replying to Li Hua.

One user, Douglas (@neonhotel), posted a heartfelt video of him writing a letter to Li Hua:

📝”Dear Li Hua, I’m sorry I didn’t get your letters. I understand you’ve been writing me for a long time, but now I’m here to reply. Hello, from your American friend. I hope you’re well. Life here is pretty normal—we go to work, hit the gym, eat dinner, watch TV. What about you? Please write back. I’m sorry I didn’t reply before, but I’m here now. Your friend, Douglas.”

Another user, Tess (@TessSaidThat), wrote:

📝”Dear Li Hua, I hope this letter finds you well. I’m so sorry my response is so late. My government never delivered your letters. Instead, they told me you didn’t want to be my friend. Now I know the truth, and I can’t wait to visit. Which city should I visit first? With love, Tess.”

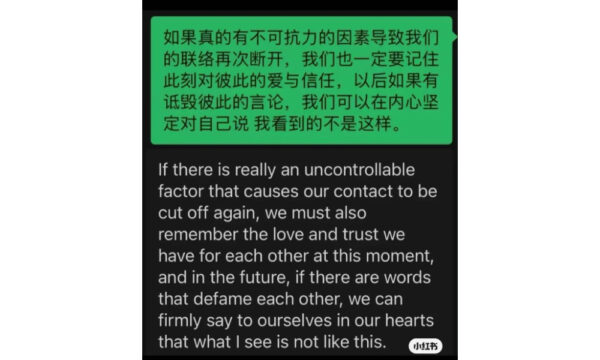

Examples of Dear Li Hua letters.

Other replies echoed similar sentiments:

📝”Dear Li Hua, I’m sorry the world kept us apart.”

📝”I know we don’t speak the same language, but I understand you clearly. Your warmth and genuine kindness transcend every barrier.”

📝”Did you achieve your dreams? Are you still practicing English? We’re older now, but wherever we are, happiness is what matters most.”

These exchanges left hundreds of users—both Chinese and American, young and old, male and female—teary-eyed. In a way, it’s the emotional weight of the distance—represented by millions of unanswered letters—that resonated deeply with both “TikTok refugees” and “Xiaohongshu natives.”

Emotional responses to the Li Hua letters.

The letters seemed to symbolize the gap that has long separated Chinese and American people, and the replies highlighted the unusual circumstances that brought these two online communities together. This moment of genuine cultural exchange made many realize how anti-Chinese, anti-American sentiments have dominated narratives for years, fostering misunderstandings.

Xiaohongshu commenter.

On the Chinese side, many people expressed how emotional it was to see Li Hua’s letters finally receiving replies. Writing these letters had been a collective experience for generations of Chinese students, creating messages to imaginary foreign friends they never expected to meet.

Receiving a reply wasn’t just about connection; it was about being truly seen at a time when Chinese people often feel underrepresented or mischaracterized in global contexts. Some users even called the replies to the Li Hua letters a “historical moment.”

✳️ Unity in a Time of Digital Divide

Alongside its political and cultural dimensions, the TikTok/Xiaohongshu “honeymoon” also reveals much about China and its digital environment. The fact that TikTok, a product of a Chinese company, has had such a profound impact on the American online landscape—and that American users are now flocking to another Chinese app—showcases the strength of Chinese digital products and the growing “de-westernization” of social media.

Of course, in Chinese official media discourse, this aspect of the story has been positively highlighted. Chinese state media portrays the migration of US TikTok users to Xiaohongshu as a victory for China: not only does it emphasize China’s role as a digital superpower and supposed geopolitical “connector” amidst US-China tensions, but it also serves as a way of mocking US authorities for the “witch hunt” against TikTok, suggesting that their actions have ultimately backfired—a win-win for China.

The Chinese Communist Party’s Publicity Department even made a tongue-in-cheek remark about Xiaohongshu’s sudden popularity among foreign users. The Weibo account of the propaganda app Study Xi, Strong Country, dedicated to promote Party history and Xi Jinping’s work, playfully suggested that if Americans are using a Chinese social media app today, they might be studying Xi Jinping Thought tomorrow, writing: “We warmly invite all friends, foreign and Chinese, new and old, to download the ‘Big Red Book’ app so we can study and make progress together!”

Perhaps the most positive takeaway from the TikTok/Xiaohongshu trend—regardless of how many American users remain on the app now that the TikTok ban has been delayed—is that it demonstrates the power of digital platforms to create new, transnational communities. It’s unfortunate that censorship, a TikTok ban, and the fragmentation of global social media triggered this moment, but it has opened a rare opportunity to build bridges across countries and platforms.

The “Dear Li Hua” letters are not just personal exchanges; they are part of a larger movement where digital tools are reshaping how people form relationships and challenge preconceived notions of others outside geopolitical contexts. Most importantly, it has shown Chinese and American social media users how confined they’ve been to their own bubbles, isolated on their own islands. An AI-powered social media app in the digital era became the unexpected medium for them to share kind words, have a laugh, exchange letters, and see each other for what they truly are: just humans.

As millions of Americans flock back to TikTok today, things will not be the same as before. They now know they have a friend in China called Li Hua.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

You may like

China Digital

Chinese Netizens Turn to Tim Cook Over Battery Factory’s Illegal Overtime

Is turning to Western suppliers an effective way for workers to pressure domestic companies into complying with labor laws?

Published

5 days agoon

March 20, 2025

We include this content in the Weibo Watch newsletter. Subscribe to get it in your inbox 📩

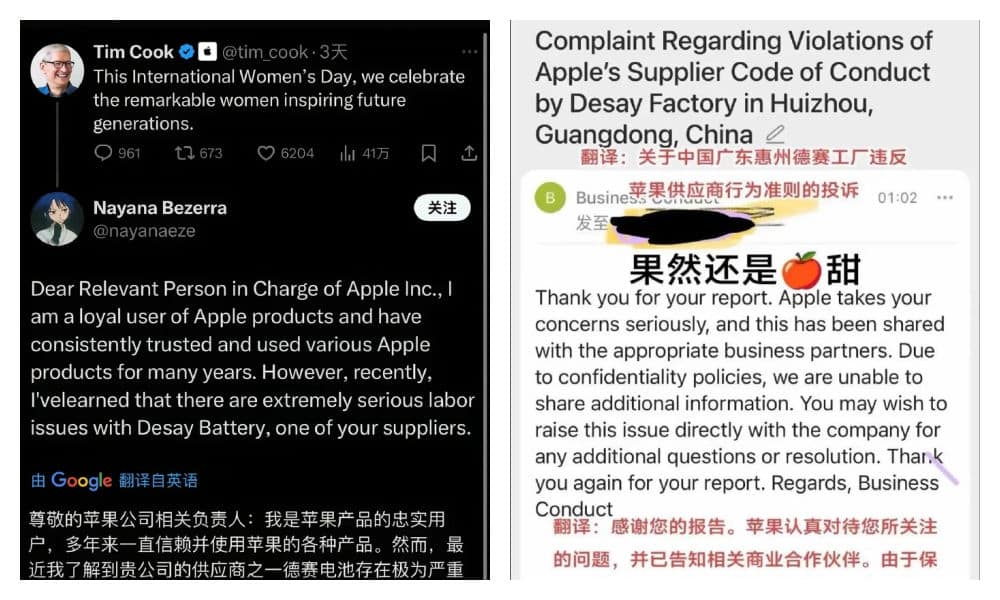

Recently, Chinese netizens have started reaching out to Apple and its CEO Tim Cook in order to put pressure on a state-owned battery factory accused of violating labor laws.

The controversy involves the Huizhou factory of Desay Battery (德赛电池), known for producing lithium batteries for the high-end smartphone market, including Apple and Samsung. The factory caught netizens’ attention after a worker exposed in a video that his superiors were deducting three days of wages because he worked an 8-hour shift instead of the company’s “mandatory 10-hour on-duty.” Compulsory overtime violates China’s labor laws.

In response, the worker and other netizens started to let Apple know about the situation through email and social media, trying to put pressure on the factory by highlighting its position in the Apple supply chain. In at least one instance, Apple confirmed receipt of the complaint. (Meanwhile, on Tim Cook’s official Weibo account, the comment section underneath his most recent post is clearly being censored.)

Screenshot of replies on X underneath a post by Tim Cook on International Women’s Day.

The factory, however, has denied the allegations, , claiming that the video creator was spreading untruths and that they had reported him to authorities. His content has since also been removed. A staff member at Desay Battery maintained that they adhere to the 8-hour workday and appropriately compensate workers for overtime.

At the same time, Desay Battery issued an official statement, admitting to “management oversights regarding employee rights protection” (“保障员工权益的管理上存在疏漏”) and promising to do better in safeguarding employee rights.

One NetEase account (大风文字) suggested that for Chinese workers to effectively expose labor violations, reporting them to Western suppliers or EU regulators is an effective way to force domestic companies to respect labor laws.

Another commentary channel (上峰视点) was less optimistic about the effectiveness, arguing that companies like Apple would be quick to drop suppliers over product quality issues but more willing to turn a blind eye to labor violations—since cheap labor remains a key competitive advantage in Chinese manufacturing.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Digital

From Weibo to RedNote: The Ultimate Short Guide to China’s Top 10 Social Media Platforms

Weibo, Wechat, Douyin, or Xiaohongshu? Understanding China’s top 10 social media platforms.

Published

1 month agoon

February 18, 2025

WHAT’S ON WEIBO CHAPTER: 15 YEARS OF WEIBO

From Weibo to WeChat, from Rednote to Bilibili, China has a unique social media landscape that is constantly evolving with the times. In this short guide to China’s social media apps, we list the top 10 most popular platforms, explaining their names, origins, and the key features that have made them successful—some of them thriving for over 25 years (!) already.

These are complicated times for social media, as users around the world are jumping between different services while holding different views on what platforms should stand for, how they should be managed, and what their role should be.

In 2025, international media are more focused on Chinese social media apps than ever before, especially after January’s “Tiktok refugee” hype in which waves of US TikTok users migrated to to China’s Xiaohongshu app.

This foreign focus on China’s online landscape also highlights lingering misconceptions, with major media outlets still trying to label Chinese apps as “the Chinese Instagram,” “the Chinese Facebook,” and so on.

Some of these labels made sense around 2010, when Chinese companies were indeed creating domestic equivalents of Twitter or Pinterest. But those apps have since evolved into something much bigger.

Over the past month, we’ve been focusing on ‘15 years of Weibo‘ for our What’s on Weibo Chapters (check out our deep dive here and the expert insight here). The story of Weibo is an example of how China’s online landscape is constantly changing, even though some major social apps are already 15, 20, even 25 (!) years old. Their secret? It’s not copying Western apps—it’s avoiding a cookie-cutter approach and embracing change. As Xiaohongshu’s Charlwin Mao (毛文超) puts it: “We don’t ask ourselves if we’re a social or commerce company—we ask, what does the consumer want?”

Xiaohongshu is no Chinese Instagram. It also wasn’t a shopping site that added reviews—it was a review site that added shopping, completely flipping traditional e-commerce models on its head. One of China’s top livestreaming apps, Kuaishou, didn’t even start as a livestreaming platform. It began as a GIF-making tool, built its user base through other platforms, then evolved into a short-video app before taking off during the livestreaming boom. Today, the company is a major player in generative AI—its Sora competitor, Kling, was born from this adaptability.

These Chinese apps have become superapps by thinking outside the box, refusing to be confined by labels, and evolving like chameleons—adapting their functions to user needs.

In these rapidly changing social media times, I thought it was high time for a short “China Social Media for Dummies” guide. This short guide breaks down the top 10 Chinese social media platforms, what they stand for, and their core features.

For this article, I have selected ten platforms or apps that are generally the most well-known in China and have the highest number of monthly active users. While the first eight social media platforms are undoubtedly the biggest eight, the ranking becomes less clear beyond that. China has a diverse range of social apps across various categories, including dating, gaming, and livestreaming. In this case, I’ve chosen the apps that are the most widely recognized in the mainstream digital landscape.

Content:

1. WeChat (微信) ⎮ “It’s a Way of Life”

2. Douyin (抖音) ⎮ “Record a Beautiful Life”

3. Weibo (微博) ⎮ “Discover New Things, Anytime, Anywhere”

4. Tencent’s QQ (腾讯QQ) ⎮ “Relax and Be Yourself”

5. Kuaishou (快手) ⎮ “Embracing Every Way of Life”

6. Bilibili (B站) ⎮ “( ゜- ゜)つロ Cheers~”

7. Xiaohongshu (小红书) ⎮ “Your Guide to Life”

8. Zhihu (知乎) ⎮ “When There’s a Question, There’s an Answer”

9. Douban (豆瓣) ⎮ “Record Your Book, Film & Music Life”

10. Baidu Post Bar (百度贴吧) ⎮ “Discuss Your Interests, Join Tieba”

1. WeChat (微信)

🚀 Launched: January 2011 by Tencent

🀄 Chinese name: 微信 Wēixìn, literally meaning “micro message.”

💬 Tagline:”微信,是一个生活方式”

“WeChat, it’s a way of life”

🔍 WeChat at a Glance:

WeChat is one of the most famous Chinese apps and is the national multifunctional ‘superapp.’ It was developed by Tencent, a social-focused tech giant that has proven its ability to understand what Chinese internet users want. Tencent has been successful in the social networking and online gaming markets since the early 2000s, and WeChat is a product of strategies it developed between the late 1990s and early 2010s. WeChat (Weixin) was an instant hit. Within a year of its launch, it already had 100 million users. By January 2013, the number had reached 300 million. Today, WeChat has over 1.38 billion monthly active users, making it the most popular app in China.

More than just a social media platform, WeChat has become a digital key to navigating daily life in China. It is hard to label this app as anything other than a ‘superapp,’ as through the years it has added so many functions that it has become one of China’s most versatile platforms. It serves as a business card, payment method, news reader, and marketing platform. For personal users, WeChat is the go-to tool for staying in touch with friends and family. For brands and businesses, it is an essential tool for building and maintaining relationships with consumers.

🔑 Some Key Features of WeChat:

● Messaging (消息): Text and voice messaging, voice and video calls, group chats (up to 500 people), file transfers (videos/documents/images), gift-giving, sending red envelopes, built-in translation, and extensive use of emojis and stickers.

● Moments (朋友圈): WeChat’s social feed, where users can share photos, videos, and updates with friends—like a private social network.

● WeChat Pay (微信支付): Digital wallet for mobile payments in both online and offline purchases. WeChat is also expanding its palmprint payment services, allowing users to pay through palm recognition scannning technology for their cashless transactions.

● WeChat Official Accounts (公众号): Allows users to follow brands, news, and services for updates, acting as a hub for business and content distribution.

● Mini Programs (小程序): Embedded lightweight apps within WeChat, offering services like food delivery, ride-hailing, shopping, and games, eliminating the need for separate app downloads.

● WeChat Channels (视频号): A short-video and livestreaming feature within WeChat, allowing users to create, share, and discover video content.

🌍 Global Influence:

WeChat is one of the most popular messaging apps in the world (although it is banned in India). WeChat and Weixin are not just different names for the same app—they have distinct functionalities. WeChat serves the international market, while Weixin is designed for the Chinese market. The two versions are distinguished by mobile numbers and operate on separate servers. One key difference is official accounts: Weixin users may not be able to search for or subscribe to official WeChat accounts available to overseas users.

📌 Important to know:

WeChat launched its QR code payments (二维码支付) in 2012, a year after Alipay. With the rise of smartphones, QR code payments made digital transactions accessible to everyone, from store owners to street vendors. WeChat’s popularity played a key role in transforming China from a predominantly cash-based society in the early 2000s to a cashless society by the late 2010s (Ghose 2024).

2. Douyin (抖音)

🚀 Launched: September 2016 by Bytedance

🀄 Chinese name: 抖音 Dǒuyīn, literally meaning “shaking sound.”

💬 Tagline: 记录美好生活

“Record a Beautiful Life”

🔍 Douyin at a Glance:

Douyin is the Chinese mainland version of the globally popular app TikTok and the country’s most popular short-video platform. From the beginning, its parent company, ByteDance (字节跳动), founded in 2012 by Zhang Yiming (张一鸣), focused on two core elements: building innovative apps and using the power of AI for content personalization. Before launching Douyin, ByteDance had already found success with Toutiao (今日头条), a highly popular news aggregator app also relying on AI-powered content personalization. Although Douyin’s focus on music, influencer culture, and short, creative videos is quite different from Toutiao’s, its success has been largely built on the recommendation systems and operational expertise ByteDance had developed through Toutiao. Before building Toutiao, Zhang Yiming worked at Microsoft, among other companies, and co-founded the real estate search engine 99fang.com.

kuaishou

Beyond ByteDance’s expertise, Douyin thrived thanks to China’s advanced 4G/5G infrastructure and a booming e-commerce industry. While Douyin initially focused on user-generated entertainment content, it has gradually evolved into a powerful multi-functional platform where users also consume and discuss the latest news and current events.

Today, Douyin and Weibo are among the most influential social platforms in China for following and discussing breaking news. Douyin is more influential in terms of active users: there are more than 760 million active monthly users (Brennan 2020; Su 2024).

🔑 Some Key Features of Douyin:

● Follow (关注): Similar to Weibo and Xiaohongshu, Douyin operates on a follower-followee network model, where users can follow others without requiring mutual follow-backs. Not every Douyin user creates videos; many are solely viewers.

● Short Video Creation (快拍): Douyin’s primary function is short video creation, either by filming directly in the app or uploading pre-recorded content from the phone’s gallery.

● AI Templates and Filters (AI创作): Douyin offers a vast range of AR filters, stickers, and special effects to make videos more attractive, fun, or engaging.

● Live Streaming (直播): Users can host live streams, interact with viewers in real time, and receive virtual gifts that can be converted into real-world earnings.

● Front Page (首页): The endlessly scrollable front page features personalized content recommended by AI algorithms based on the user’s profile, location, preferences, and interactions.

● Friends (朋友): Users can import contacts from WeChat or QQ and see their videos directly within the app.

● Private Messaging (消息): Douyin supports private direct messaging with group chat options for private conversations and social interactions.

● Douyin Trending Lists (抖音热搜): Users can explore trending topics and hot searches. These lists are segmented into categories such as live streaming, films, brands, and music, offering insights into what’s currently popular.

● Douyin Mall (抖音商城): Douyin’s in-app e-commerce platform, which delivers a personalized shopping experience by recommending products based on user data and preferences.

🌍 Global Influence:

It is clear that ByteDance has significant international ambitions—and with great success. No other Chinese digital product has conquered the global market in the same way as TikTok, the international version of Douyin. In 2017, ByteDance acquired the app Musical.ly, which was already popular in the U.S. and Europe, in a strategic move to rapidly integrate TikTok into the Western market. Today, TikTok boasts over 1.5 billion users worldwide. However, the app’s global influence is not without controversy. TikTok has been banned in India, and since 2020, plans to ban it in the United States have repeatedly surfaced. TikTok sits at the center of geopolitical tensions between the U.S. and China, symbolizing broader concerns about China’s growing technological power and influence.

📌 Important to know:

TikTok and Douyin are similar in many ways, but they are two separate apps. Douyin is not available in foreign app stores like Google Play or the international Apple Store, while TikTok is not available in Chinese app stores. The apps feature different content and different popular creators. Content moderation on the two platforms also differs significantly. Internationally, TikTok’s moderation follows practices similar to other global platforms, with rules on hate speech, harassment, nudity, and other forms of inappropriate content. In contrast, Douyin adheres to strict Chinese internet regulations and censorship laws, enforcing different and much broader rules on what can be posted. These differences, along with varying cultural norms and regulatory environments, have transformed Douyin and TikTok into two distinct platforms in terms of content and user experience.

3. Weibo (微博)

🚀 Launched: August 2009 by Sina

🀄 Chinese name: 微博 Wēibó, literally meaning “micro blog.”

💬 Tagline: 随时随地发现新鲜事

“Discover new things anytime, anywhere”

🔍 Weibo at a Glance:

Weibo launched in 2009 as a Chinese equivalent of Twitter but quickly evolved into much more—a uniquely Chinese, versatile, and dynamic platform where users follow celebrities, media influencers, and stay up to date on the latest news. Over the past fifteen years, Weibo has become China’s primary digital space for public discourse on unfolding events. Even today, despite a more decentralized social media landscape in China, Weibo remains China’s online ‘living room’ where people follow and discuss news and entertainment, and the platform still has about 580 million monthly active users. To learn all about Weibo’s journey, check out our detailed report here.

🔑 Some Key Features of Weibo:

● Follow (关注): Unlike friend-based systems like Facebook or WeChat Moments, Weibo operates on a follower-followee model: users can follow others without requiring mutual follow-backs. This also means that some celebrities, such as Xie Na (谢娜), have accumulated over 120 million followers throughout the years.

● Microblogging (发微博): The core feature of Weibo is posting short messages, which can include videos and images. Initially limited to 140 characters, users can now post up to 5,000 Chinese characters. If longer than that, users can change a post into a separate blog article.

● Hot Topics (微博热搜): Weibo provides trending topic lists, hashtags, and rankings of popular influencers across different categories—from general hot lists and headlines to more niche areas such as entertainment, gaming, movies, sports, and more. This feature helps users stay up to date with the latest trends in their fields of interest.

● Video (视频): A video-only feed curates hot videos based on algorithms, comparable to YouTube Shorts or TikTok.

● Super Topics (超级话题): These are niche communities dedicated to specific interests, similar to subreddits. (Read more here.)

● Private Messaging (消息): Weibo supports private direct messaging with group chat options.

🌍 Global Influence:

Weibo is not very international. Although the platform allows international users to register, only a limited number of countries can do so based on their phone numbers. Eligible countries include Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Thailand, India, the UK, USA, Spain, Italy, Germany, and a few others. Meanwhile, many countries are excluded—such as nearly all Northern European and African nations, along with most countries in South America. Despite these restrictions, Weibo remains a key platform for foreign entities engaged in China-focused marketing or diplomacy. As a result, most foreign embassies in China maintain official Weibo accounts, as do tourism bureaus, international brands, and major global celebrities, including actors, athletes, and DJs.

📌 Important to know:

Although trending topics on Weibo are often related to entertainment, society, and news events, Weibo is also highly Weibo-focused. Many of its trending topics originate on the platform itself—such as viral comments, new features or guidelines, celebrities’ posts, or Weibo-related events and contests (Weibo, as a company, frequently organizes and sponsors events ranging from entertainment to sports). This has created a distinct Weibo culture, more reminiscent of Western platforms like Reddit than X/Twitter or Facebook.

4. Tencent’s QQ (腾讯QQ)

🚀 Launched: February 1999 by Tencent

🀄 Chinese name: QQ: “Q” and “QQ” are also used for “cute.”

💬 Tagline: “轻松做自己”

“Relax and be yourself”

🔍 QQ at a Glance:

QQ has always been known as China’s most powerful instant messaging software. It is also one of China’s oldest social media platforms, and in many ways, its success paved the way for WeChat to thrive. Launched by Tencent in 1999 under the name OICQ, this instant messaging service was China’s counterpart to the Israeli software ICQ, developed in 1996 and later acquired by AOL. Following a lawsuit from AOL, Tencent rebranded the application as QQ. As the platform partnered with pager services and mobile communication companies, QQ was initially used on pagers, personal computers, and for SMS services. Over time, QQ evolved and is now primarily used on smart mobile devices. In 2005, Tencent introduced QZone (QQ空间), a social media platform integrated with QQ, where users can share updates, photos, videos, and more with friends.

For many people, QQ is a nostalgic part of their childhood—comparable to MSN Messenger in the West. As WeChat rose in popularity, many users migrated to it, particularly since Tencent made it easy to import all QQ contacts into WeChat. Despite this shift, QQ remains actively used, especially among young people and fans of ACG (anime, comics, and games), as well as older users who rely on it for work-related purposes such as file sharing and communication. In fact, according to Tencent’s 2024 financial report, QQ’s mobile monthly active users still reached 554 million, demonstrating its lasting influence in China’s social media landscape even after 25 years (Negro et al 2020; Yidong Huliangwang 2024)

🔑 Some Key Features of QQ:

● Messaging (消息): Text and voice messaging, voice and video calls, group chats, and customizable profile styles, chat decorations, and themes.

● Groups (QQ群): QQ Groups are like chatrooms for users with shared interests, managed and guided as community spaces.

● File Management/Online Storage (文件传输): Group file sharing, large file uploads, and permanent file storage—unlike WeChat, QQ stores files permanently and can handle larger files.

● Mail (QQ邮箱): An email service hosted by QQ.

● Wallet (QQ钱包): Top up phone credit, pay off credit card bills, and settle utility fees for water, electricity, and gas.

● Super QQ Show (QQ秀): A customizable avatar feature where users can dress up and design their online persona which can be used across QQ-related platforms, using accessories that can be purchased with QQ Coins (QQ币).

● QQ Games (QQ游戏): Access and play games directly within the app or through linked gaming platforms.

🌍 Global Influence:

QQ is very much a domestic app. It’s not particularly easy for foreigners to register either. If you use a foreign phone number, verification messages often fail to arrive, or the app may flag your number as “suspicious” or “not secure.” If you use a Chinese phone number, registration requires a Chinese name and ID number. While there are certainly foreigners on QQ, it’s clear that making the app more foreigner-friendly is not a priority for Tencent.

📌 Important to know:

Besides its file transfer feature, QQ’s group function is also quite popular, offering much larger group capacities compared to WeChat. QQ Groups cover a wide range of topics, from web novels to cryptocurrency, attracting communities of all kinds. Depending on the group type, VIP members can create groups with up to 2,000 members, while certified members can host groups with up to 5,000 members. In the past, QQ Groups have faced backlash for hosting vulgar or inappropriate content, leading to hefty fines for Tencent and increased moderation efforts.

5. Kuaishou (快手)

🚀 Launched: March 2011, but under different name (GIF快手) as a GIF-making tool.

🀄 Chinese name: 快手 Kuàishǒu, literally meaning “fast hand.” Its international name is “Kwai.”

💬 Tagline: 快手,拥抱每一种生活

“Kuaishou, embracing every way of life”

🔍 Kuaishou at a Glance:

China has many different apps for sharing videos and livestreaming, but Kuaishou holds a unique place in this crowded digital landscape. Why? Unlike most other popular social apps in China, Kuaishou’s content and user base are deeply rooted in the country’s smaller towns and rural areas—over 60% of its users come from rural communities. As a result, Kuaishou has become the go-to app for content related to authentic rural lifestyles and agriculture, setting it apart from apps like Douyin or Xiaohongshu, which primarily cater to urban, middle-class users in higher-tier cities (Ran 2024, 3). Kuaishou’s success story (the app has around 500 million monthly active users) reflects that of many other Chinese digital giants—it has evolved with the times, continuously adapting to user needs instead of following a cookie-cutter approach or a ready-made formula.

Launched in 2011 as a GIF-making tool during Weibo’s golden era, the platform later transformed into a short-video app.Founded by Su Hua (宿华) and Cheng Yixiao (程一笑), Kuaishou benefited from strong technical expertise. Before co-founding the platform, Su worked as a software engineer at both Google and Baidu. Kuaishou’s major mainstream breakthrough came in 2016, when it introduced livestreaming, which quickly became a core part of the platform. Since 2020, the platform has focused more on e-commerce and has integrated it into the app in various ways, making it an appealing option for rural merchants and aspiring influencers. By 2021, half of all rural creators on Kuaishou were generating income from the platform (Ran, 2024, 1).

🔑 Some Key Features of Kuaishou:

● Short Video Feed (短视频): Kuaishou’s main function is sharing and scrolling through short videos, covering everything from gaming and cooking to news events and memes. Through the app’s “Discovery” (发现) feature, you can find new creators and follow more people.

● Live Streaming (直播): Kuaishou offers a wide range of livestream channels available at all hours, from gaming to e-commerce, often blending shopping and entertainment.

● Special Filters: Like Douyin or Snapchat, Kuaishou provides a variety of video effects and templates so that users can post creative videos.

● Kuaishou Shop (快手小店): Kuaishou’s in-app e-commerce platform offers a wide selection of products, including household items, food, and cosmetics.

● Kuai Coins (快币): Kuaishou users can top up their accounts with ‘Kuai Coins’ (Kuaibi), the platform’s virtual currency. These can be used to purchase virtual gifts to support content creators or unlock paid content.

🌍 Global Influence:

Within mainland China, Kuaishou’s strength lies in its focus on second- and third-tier cities as well as rural areas, meaning it is not necessarily focused on expanding its global influence with this particular app. However, similar to the domestic vs. foreign approach of Douyin and TikTok, Kuaishou released an international version of its app called Kwai, though it did not achieve the same level of success as TikTok. Another Kuaishou product with a much greater international impact is its self-developed video generation model, Kling (可灵), also known as KLING AI. Initially, Kling started as a feature within Kuaishou’s video editing app, KuaiYing (快影), in China but was later launched internationally, gaining recognition as a powerful AI model and a possible alternative to OpenAI’s Sora.

📌 Important to know:

Kuaishou is known for increasing its market share by partnering up with other powerful platforms or brands. For example, the company has partnered with Chinese shopping/food delivery platform Meituan since 2021 in the local life services sector. For its e-commerce livestreaming, Kuaishou previously joined forces with JD.com. To drive more traffic to its platform, Kuaishou also established partnerships for copyright and content with various international sports events, including the NBA and the UEFA Champions League, as well as the Tokyo and Paris Summer Olympics, along with the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics and the 19th Asian Games Hangzhou.

6. Bilibili (B站)

🚀 Launched: June 26, 2009 by Xu Yi (徐逸)

🀄 Chinese name: 哔哩哔哩 Bìlī Bìlī, doesn’t really mean anything but sounds cute and vibrant, like beep beep. Bilibili is more commonly referred to as “B站,” meaning “B-station.”

💬 Tagline: (゜-゜)つロ干杯~-bilibili

“Cheers to Bilibili” [not literally, but that’s what this symbolic motto conveys]

🔍 Bilibili at a Glance:

Bilibili is China’s online home for fans of anime, comics, games (ACG), and technology. While the video streaming platform started as a niche community, it has since grown into one of the go-to video-sharing platforms for China’s Generation Z. Founder Xu Yi (徐逸) designed the earliest version as an improved alternative to existing video-sharing platforms, particularly the ACG hub ACfun (also known as A站, A-station). Although Bilibili remains heavily centered on anime, music, esports, and gaming culture, the platform now hosts a vast range of content, with creators covering topics such as culture, education, and social commentary. Bilibili allows both amateur and professional creators/channels to upload content, as well as producing in-house content, making it a diverse and dynamic platform where users can find everything from unpolished vlogs to Chinese anime series or BBC and History Channel documentaries. This has led to “B Station” becoming a versatile platform used by some 348 million users on a monthly basis. A unique aspect of Bilibili is its user engagement system. One way the platform helps maintain content quality is by requiring users to first answer a set of questions before posting comments and videos. Official members can also go through six membership levels, each unlocking various platform privileges, fostering a stronger sense of community and rewarding user engagement.

🔑 Some Key Features of Bilibili:

● Home of Video Streaming (首页): On Bilibili’s main page, users can explore the latest trending videos or discover new content across various categories, from anime series (番剧) to entertainment (娱乐) and music (音乐).

● Bullet Comments (弹幕评论): Bullet comments, or danmu, are real-time floating texts overlaid on videos, creating an interactive and communal viewing experience. Bilibili was the first Chinese platform to adopt this feature, which has since become its signature function.

● Livestreaming (直播): Users can browse Bilibili’s livestreaming rooms, where they’ll find a variety of live gaming streams, as well as study sessions, homework help, and other interactive content.

● Bilibili Game Center (游戏中心): A platform for game distribution, reviews, and gameplay videos, covering both mobile and PC gaming content.

● Bilibili Manga (哔哩哔哩漫画): A section dedicated to reading and discussing manga, including licensed and original works.

● Bilibili Classroom (哔哩哔哩公开课): Educational content featuring tutorials, lectures, and courses on a wide range of topics.

● Bilibili Shopping (会员购): An integrated e-commerce section where Bilibili members can purchase merchandise, anime goods, and other products related to content creators and the Bilibili platform.

🌍 Global Influence:

Since Bilibili is focused on ACG, it has some niche global appeal among those interested in anime, gaming, and East Asian pop culture. However, beyond these communities, its global influence remains quite limited. In addition to being primarily geared toward Chinese-speaking users, much of the platform’s content is also subject to copyright restrictions outside of China, making it difficult or even impossible for many international viewers to access professional channels on the site.

📌 Important to know:

Like Weibo, Bilibili is a company that focuses on building communities and fostering a unique “Bilibili Culture.” Since 2010, Bilibili has been the main initiator, host, and/or sponsor of various popular events, most famously its Bilibili Spring Festival Gala. Additionally, Bilibili actively contributes to the growth of the Chinese anime industry by financing and co-producing anime content while also making efforts to distribute Chinese anime globally.

7. Rednote/Xiaohongshu (小红书)

🚀 Launched: June 2013 by Charlwin Mao (毛文超) and Miranda Qu (瞿芳)

🀄 Chinese name: 小红书 Xiǎohóngshū, literally meaning “Little Red Book.”

💬 Tagline: 你的生活指南

“Your Guide to Life”

🔍 Xiaohongshu at a Glance:

Is it Xiaohongshu, Rednote, or RED? In China, there is actually only one name for this “little red app”: Xiaohongshu. The Shanghai-based platform began as an online international “shopping guide” where users posted independent reviews (videos, text, images) of luxury products and cosmetics they had purchased. Over time, it evolved into a broader lifestyle community focused on travel, fitness, fashion, and overseas experiences. As the app gained popularity, the products reviewed by users also started being distributed through the platform itself—flipping the traditional e-commerce model on its head. Instead of a shopping site with reviews, Xiaohongshu became a review site that seamlessly integrated e-commerce. “We don’t ask ourselves if we’re a social or a commerce company,” Xiaohongshu co-founder Charlwin Mao once said: “We ask, ‘what does the consumer want?’” (Rowan 2016).

By 2025, Xiaohongshu’s influence is undeniable. With over 300 million monthly active users, the majority of whom are young, urban, and female, it has become an essential part of China’s online ecosystem. What sets Xiaohongshu apart is its ability to blend genuine real-life experiences with online sharing and offline consumption, creating a truly unique digital space.

🔑 Some Key Features of Xiaohongshu:

● Discover (发现): the core function of Xiaohongsu is the personalized homepage (首页), where users can discover new user-generated content, either based on interest through data-driven algorithms, or based on location, giving an overview of content that was posted near to you.

● Post a Note (发布笔记): All users can create content Xiaohongshu and post either videos, images, text, writing reviews, sharing tips, or document experiences. In doing so, they can tag products and link directly to e-commerce listings.

● Shopping (购物): Xiaohngshu is both a social app and a shopping plaform: users can browse and buy products without leaving the app. The stores selling the products can also be ‘followed’ to stay in touch.

● Live Streaming (直播): Xiaohongshu has a livestream feed, where users can scroll through thousands of different livestreams happening simultaneously. These streams range from people singing and teaching English to selling products, cooking, or giving makeup tutorials.

🌍 Global Influence:

Since much of its content has always revolved around overseas shopping experiences, Xiaohongshu has been inherently global from the start, catering primarily to overseas Chinese users. As a result, the app has been available in foreign app stores and allowed international users to sign up. However, nobody expected Xiaohongshu to become a global sensation overnight in January 2025. With a potential TikTok ban looming in the U.S., millions of American TikTok users began seeking alternative platforms. The most notable destination for these users was Xiaohongshu/Rednote, which saw a massive influx of so-called “TikTok refugees” (TikTok难民). This sudden surge propelled Xiaohongshu to the #1 spot in app stores across the U.S. and beyond. The arrival of over three million foreign users marked an unprecedented milestone for a domestic Chinese app, bringing Xiaohongshu into the global spotlight. Though not all of these TikTok users may stay long-term, and TikTok wasn’t banned after all, the event cemented Rednote’s instant fame. In response, the platform has taken proactive steps to internationalize, including hiring foreign content moderators and launching a one-click translation feature for seamless cross-language interaction.

📌 Important to know:

Gender demographics inevitably play a role on all social media platforms, but this holds especially true for Xiaohongshu, as its user base is overwhelmingly female—approximately 80% of its users are women, while only about 20% are men. This is very different from platforms like Bilibili or Zhihu (which have more male users) or WeChat, where gender demographics are more balanced. Since the platform is targeted toward educated, wealthier, and predominantly female users, its content naturally reflects these demographics. When combined with its strong e-commerce aspect, Xiaohongshu stands out as a unique platform that is far more about lifestyle, shopping, and real-life experiences than it is about politics, economics, or news events.

8. Zhihu (知乎)

🚀 Launched: January 26 2011, with funding from, among others, Tencent and Sogou.

🀄 Chinese name: 知乎 Zhīhū, which is usually left untranslated, but with 知 (zhī) meaning knowledge and 乎 (hū) serving as a classical particle for a question or emphasis, the meaning could be loosely translated as “Do you know?”

💬 Tagline: 有问题,就会有答案

“When there’s a question, there’s an answer”

🔍 Zhihu at a Glance:

Zhihu is most commonly known as the Chinese version of the American question-and-answer website, Quora. While Quora was founded in 2009, Zhihu was launched in 2011 and has been growing steadily ever since. It is recognized for its relatively high-level discussions, often focusing on topics such as society, economy, business, history, law, and many other areas. Users can submit both questions and answers, with the best answers being upvoted and placed at the top of the thread. Some popular contributors have answered thousands of questions, with many responses resembling mini-essays. Zhihu has over 80 million monthly active users. Unlike many other Chinese social media platforms, it has a slight majority of male users (51.5%), with most of its users being highly educated. (Bao 2024, 1).

🔑 Some Key Features of Zhihu:

● Q&A: The core function of Zhihu is either posting a question (提个问题) or replying to a question (回答问题).

● Zhihu Homepage (首页): On the main homepage, users get an overview of recommended posts. They can also select from various categories—ranging from science to law—and view the most popular posts across different topics.

● Live Streaming (直播): Zhihu offers a livestreaming feature, where users can scroll through livestreams and post reactions or questions in real time.

● Zhihu Direct Answer (知乎直答): Zhihu has also introduced the “Zhihu Direct Answer” AI model, which integrates the DeepSeek-R1 model to allow users to ask questions and receive direct answers through a chatbot.

● Zhihu Podcast Square (播客广场): Zhihu’s opodcast squore’ is a place where Zhihu users can listen and subscribe to podcasts.

🌍 Global Influence:

Unlike many other Chinese apps, Zhihu is available on foreign app stores, such as Google Play, and allows users from a wide range of countries to sign up. Nevertheless, the platform remains primarily China-focused, with Chinese as the main language. While Zhihu is popular among overseas Chinese communities, it lacks significant global influence.

📌 Important to know:

In the AI era, where chatbots can quickly provide direct answers to almost any question, traditional question-and-answer platforms risk losing relevance. Zhihu, however, is using AI tools to its advantage by integrating an AI-powered search function and a DeepSeek-based chatbot to handle straightforward queries. By doing so, Zhihu is positioning itself as the go-to platform for reliable answers and diverse perspectives offered by both authentic users and AI.

9. Douban (豆瓣)

🚀 Launched: March 2005

🀄 Chinese name: 豆瓣 Dòu Bàn, literally means the “cotyledon of a bean” but the platform was actually named after a Beijing hutong (traditional alley) (Shen 2019).

💬 Tagline: 来豆瓣,记录你的书影音生活

“Come to Douban, record your book, film & music life”

🔍 Douban at a Glance:

Douban is China’s online home of books, music, movies, and more. The site has been around for two decades already, and thus was originally very much desktop-based. While Douban is primarily a review site, it has evolved into a vibrant online community of “Douban friends” (豆友们), where users can explore and discuss the latest films, connect with people who share similar interests, look up events, and seek advice on anything from work-related problems to love and relationships. Douban has approximately 60 million monthly active users and a much larger base of about 200 million registered users. Most importantly, it’s the go-to platform for checking the latest ratings and reviews on blockbuster movies and highly anticipated TV dramas.

🔑 Some Key Features of Douban:

● Movie Reviews and Ratings (豆瓣电影): ‘Douban Movie’ is one of Douban’s core features. Similar to IMDb, it enables users to explore reviews, blogs, and ratings for the latest films, discuss trending topics in the world of cinema, and search for the highest- or lowest-rated movies.

● Books and Music (豆瓣读书, 豆瓣音乐): In line with ‘Douban Movie,’ these sections offer similar functionalities for books and music, allowing users to post reviews and discover new titles or albums within their favorite genres.

● Groups and Forums (豆瓣小组): Douban Groups allow users to join or create communities centered on specific interests, such as hobbies, professions, or niche topics.

● Event Listings (同城活动): This feature helps users discover upcoming local events, from exhibitions and workshops to concerts and meetups.

● Douban Merchandise (豆瓣豆品): An online shop offering a range of unique products, including bookmarks, notebooks, sweaters, and umbrellas.

🌍 Global Influence:

Douban is open to international users, but with its community-driven approach, it remains heavily China-focused, particularly in its selection of books, movies, and event listings. In the English-language social media space, platforms like Goodreads, IMDb, and Reddit already offer many of the same functions as Douban.

📌 Important to know:

China has an incredibly vibrant TV drama industry. With so many new dramas released every month, many people rely on Douban ratings to decide which ones are worth watching and which they can skip.

10. Baidu Post Bar (百度贴吧)

🚀 Launched: December 2003 by Baidu

🀄 Chinese name: 百度贴吧 Bǎidù Tiēbā: Baidu Post Bar

💬 Tagline: 聊兴趣,上贴吧

“Discuss interests, join Tieba”

🔍 Baidu Tieba at a Glance:

Baidu Tieba is an online social media forum where users can explore various ‘bars’—online groups dedicated to specific topics. As a discussion platform divided into thousands of communities, it is somewhat similar to the American platform Reddit. On Baidu Tieba, people can follow and participate in all kinds of groups, from Beijing-focused ones to parenting groups, specific film and arts groups, or those dedicated to tech or business. There are thousands, even millions, of different topic boards to explore, with each ‘bar’ forming its own community.

In its heyday, Baidu Tieba had around 500 million monthly active users, but this number has decreased over the years. In 2021, there were reportedly only about 37 million monthly active users left (Sanyi Shenghuo). In China’s current social media era, Baidu Tieba might not have done enough to compete with newer and more innovative platforms. Although other platforms, such as the Chinese video livestreaming services Huya (虎牙) or YY (YY直播), likely have a stronger presence in terms of active users, Baidu Tieba remains more well-known because it has been around for so long and has become a household name when it comes to China’s internet.

🔑 Some Key Features of Baidu Tieba:

● Topic-Based Communities (贴吧): The core function of Baidu Tieba is its tieba (贴吧), which are topic boards or discussion-based communities. On the main page, users can explore trending topics across various major communities.

● Live Streaming (直播): Baidu Tieba also features a livestreaming function, allowing users to explore various ongoing livestreams. Many streamers broadcast simultaneously across multiple platforms to maximize their earnings through virtual gifts and monetization.

● Chat Rooms (聊天频道): Baidu Tieba’s communities include dedicated chat channels where members can engage in direct conversations.

● Topic Moderators (吧主): Each topic board has its own moderators (吧主), who are responsible for managing discussions and moderating content within the community.

● AI Square (AI广场): AI Square (AI广场) is a feature within Baidu Tieba that integrates AI-driven interactions across different topic boards. For example, in the parenting community, users can chat with AI-generated “mothers” to seek advice on child-rearing, feeding babies, and other parenting topics.

🌍 Global Influence:

Baidu Tieba is aimed at domestic audiences. Although Baidu as a company has global ambitions and international influence, its worldwide efforts do not extend to Baidu Tieba, which remains a classic representation of China’s Web 2.0 era.

📌 Important to know:

Baidu Tieba is an important part of China’s internet history. Many of the country’s most famous viral trends and memes from the 2005–2010 era originated on Baidu Tieba, which became an influential platform due to its decentralized structure—managed by communities rather than a central authority. Words like “diaosi” (屌丝, loser) and “tuhao” (土豪, filthy rich), both of which remain widely used today, first gained popularity on Baidu Tieba. Although Baidu Tieba has lost its relevance as a leading platform for online discussions in China, its impact on the country’s internet culture continues to this day (Edward Shuo 2024).

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

References

◾ Brennan, Matthew. 2020. Attention Factory: The Story of TikTok and China’s ByteDance. ChinaChannel. https://amzn.to/3X2CEwS

◾ Edward Shuo/Edward说. 2024. “Baidu Tieba from Glory to Decline: Robin Li Abandoned Baidu Tieba [百度贴吧辉煌到没落,李彦宏放弃百度贴吧].” QQ News, August 26. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://news.qq.com/rain/a/20240826A04ZJT00

◾ Ghose, Ronit. 2024. Future Money: Fintech, AI, and Web3. London: Kogan Page.

◾ Negro, Gianluigi, Gabriele Balbi and Paolo Bory. 2020. “The Path to WeChat: How Tencent’s Culture Shaped the Most Popular Chinese App, 1998–2011.” Global Media and Communication 16 (2): 208-226.

◾ Yidong Huliangwang 移动互联网. 2024. “Why Are So Many People Still Using QQ [为什么还有那么多人在用QQ]?” Tencent Research Institute 腾讯研究院, March 27. Accessed February 13, 2025. https://www.tisi.org/27710/.

◾ Ran Xi. 2024. “Rural Chinese Youth on Kuaishou: Performing Gender, Labor, and Rurality.” Journal of Youth Studies, August 19.

◾ Rowan, David. 2016. “China’s $1bn Shopping App Turns Everyone Into Trendspotters.” WIRED Magazine, April. Accessed February 19. https://www.wired.com/story/little-red-book-xiaohongshu-crowdsourced-shopping-app/.

◾ Sanyi Shenghuo 三易生活. 2021. “Baidu Tieba’s User Loss of Nearly 90% in Five Years? The Past Is Gone, Let’s Look at Today—Is Baidu Tieba Exiting the Historical Stage? [百度贴吧五年用户流失近九成?前浪已过且看今朝——百度贴吧要退出历史舞台了吗?]” Jiemian, October 29. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www.jiemian.com/article/6759080.html

◾ Shen, Xinmei. 2019. “How Douban Went from China’s IMDB to Its ‘Spiritual Corner’.” South China Morning Post, October 15. Accessed February 16, 2025. https://www.scmp.com/abacus/who-what/what/article/3100865/how-douban-went-chinas-imdb-its-spiritual-corner.

◾ Su, Chunmeizi. 2024. Douyin, TikTok and China’s Online Screen Industry: The Rise of Short-Video Platforms. London & New York: Routledge.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

What’s on Weibo Chapters

Subscribe

Squat or Sit? China’s Great Toilet Debate and the Problem of Footprints on the Seat

Weibo Watch: The Great Squat vs Sitting Toilet Debate in China🧻

Chinese Netizens Turn to Tim Cook Over Battery Factory’s Illegal Overtime

Revisiting China’s Most Viral Resignation Letter: “The World Is So Big, I Want to Go and See It”

The 315 Gala: A Night of Scandals, A Year of Distrust

Our Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Beyond the Box Office: What’s Behind Ne Zha 2’s Success?

Weibo Watch: Christmas in China Is Everywhere and Nowhere

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

12-Year-Old Girl from Shandong Gets Infected with HPV: Viral Case Exposes Failures in Protecting Minors

15 Years of Weibo: The Evolution of China’s Social Media Giant

Tuning Into the Year of the Snake

The ‘China-chic Girl’ Image and the Realities of China’s Competitive Food Delivery Market

TikTok Refugees, Xiaohongshu, and the Letters from Li Hua

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight11 months ago

China Insight11 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music12 months ago

China Music12 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

-

China Arts & Entertainment10 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment10 months agoSinging Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments