Featured

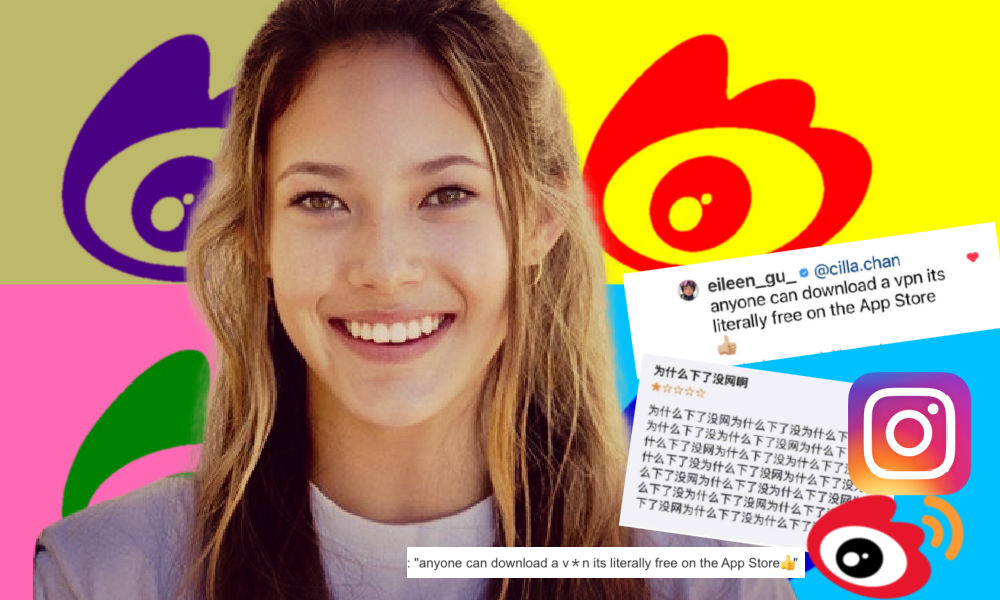

Eileen Gu’s “It’s Literally Free” Comment Regarding Chinese Internet Freedom and VPN Use

Some feel that Eileen Gu’s “it’s literally free” comment shows how utterly unaware the American-born athlete is of her privileged position.

Published

3 years agoon

An Instagram comment by the American-born athlete Eileen Gu competing for China in the Winter Olympics is making its rounds on Weibo, where many point out that what Gu thinks is ‘literally free’ is not so free at all.

Over the past week, the 18-year-old Chinese American freestyle skier Gu Ailing (谷爱凌 Eileen Gu) has become an absolute social media sensation in China. After grabbing the gold medal for China, the “snow princess” is widely celebrated. But some Weibo users were irked by a comment Gu recently made online.

On February 10th, reporter Shen Lu at Protocol.com reported about the noteworthy exchange on Eileen Gu’s Instagram account, which has one million followers.

Underneath a post by Eileen Gu of February 7th (before the Olympic athlete would win gold at Women’s Freeski Big Air event), someone named ‘Cilla.chan’ wrote:

“Why can you use Instagram and millions of Chinese people from mainland cannot, why you got such special treatment as a Chinese citizen. That’s not fair, can you speak up for those millions of Chinese who don’t have internet freedom”

Eileen Gu herself then replied:

“Anyone can download a VPN its literally free on the App Store [thumbs up]”

As a screenshot of the exchange also circulated on Chinese social media platform Weibo, there were many netizens who were surprised about Gu’s statement, since VPNs are generally not available on app stores in mainland China.

“Can we get it [a VPN] for free?” some wondered, with others commenting: “There is no [VPN] on the national app stores.”

In China, there are numerous restrictions on virtual private networks (VPNs), which are commonly used to browse websites or apps that are otherwise blocked in China. Over the past few years, Chinese authorities have tightened control over unapproved use of VPNs. In 2017, one Chinese man running a small-scale website on which he sold VPN software was sentenced to nine months in prison.

With her comment, Gu also seemed to suggest that ‘internet freedom’ simply refers to the accessibility of foreign (social) media sites in mainland China.

In another thread on Weibo, it was suggested that Gu had just wanted to defend China.

One Weibo user mentioned Gu’s privilege, and how they were jealous at the “cruel naivety” (“残忍天真”) which allowed her to claim that “anyone could download a ***, it’s literally free on the App Store.” Others also commented how they were envious of how blissfully unaware she seemed to be about her own privilege.

Gu’s reply seems to have become somewhat of an online catchphrase now, with some people replacing ‘VPN’ with other things.

“Anyone can have dual citizenship, it’s literally free on the App Store [thumbs up],” some Weibo users said, poking fun at the speculation surrounding Gu’s nationality (the athlete supposedly naturalized and surrendered her American passport but reporters’ question on whether or not she actually did have been avoided, read more here).

“Anyone can download a Beijing residence permit.”

“Anyone can download a Hainan, it’s literally free on the App Store,” another person wrote, referring to a viral video in which Gu said she had never been to Hainan before.

Others wrote: “Anyone can download a oops-what-is-this, it’s literally free on the appstore,” avoiding the use of the word ‘VPN,’ which is a sensitive term on Chinese social media.

“Literally free, actually, technically and practically forbidden,” someone wrote. “My life is also literally free,” one commenter said.

Another person wrote: “Everday I’m seeing Weibo posts I wrote disappearing. Hahahaha: literally free.”

One post going viral on Weibo at the moment is a screenshot of someone warning other mainland Chinese Instagram users that online authorities are supposedly tracking down Chinese citizens on the American platform. This image was also reposted by many with the “It’s literally free” comment.

But there are also those defending Gu, mentioning that the Olympic freestyle skier is only a teenager: “Forget it, she’s still very young.” “She really just doesn’t know,” another comment said.

Despite those criticizing Gu over the “literally free” comment, Eileen Gu is still Weibo’s “snow princess” and many appreciate her sometimes snarky way of responding to difficult questions.

Others, however, do think that the Olympic athlete has a lot to learn: “If Eileen Gu hadn’t made the ‘it’s literally free’ comment I wouldn’t have thought anything negative about her, but this one sentence has revealed that she is part of a structural problem.”

By Manya Koetse

(PS If actually you need a VPN at this time, Express VPN is currently doing a Winter Olympics special, offering 3 extra months free with the purchase of a 12-month plan. Check here. )

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2022 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

Chinese Movies

The Unstoppable Success of Ne Zha 2: Breaking Global Records and Sparking Debate on Chinese Social Media

Everyone’s talking about Ne Zha 2—from in-depth online analyses to the booming market surrounding the film.

Published

1 day agoon

February 25, 2025

China’s animated blockbuster Ne Zha 2 (哪吒之魔童闹海) is smashing box office records and igniting debates on Chinese social media—from its most popular supporting characters to the question of which town can truly claim Nezha as its own.

The Chinese animation blockbuster Ne Zha 2 (哪吒之魔童闹海) has been a major point of discussion in China recently—not just for the movie itself, but also for its box office performance, which has become a hot topic on Weibo and beyond.

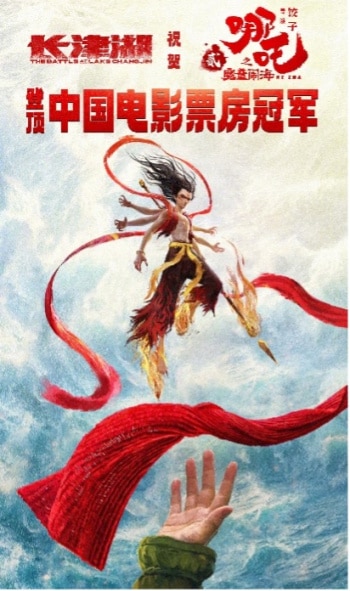

Just nine days after its release on January 29, Ne Zha 2 had already surpassed the 2021 film The Battle at Lake Changjin (长津湖), which had previously held the title of the highest-grossing Chinese film of all time—surpassing Wolf Warrior 2 (战狼2).

China’s top 3 highest-grossing movies: Ne Zha 2, Battle at Lake Changjin, and Wolf Warrior 2

In mid-February, Chinese netizens were eagerly anticipating Ne Zha 2 reaching the 10 billion yuan milestone (about $1.37 billion). At the time, the film had already grossed over 9.8 billion yuan ($1.35 billion), securing its place as the 17th highest-grossing film worldwide and the only non-Hollywood film in the top 20.

Now, the film’s global box office performance has surpassed all expectations: it has exceeded 13.8 billion yuan ($1.90 billion) as of February 25, placing Ne Zha 2 among the top eight highest-grossing films of all time worldwide. On Tuesday, it already became the highest-grossing animated film in global history.

In response to the film’s overwhelming success, there have been all kinds of memes, trends, and hashtags on Chinese on social media.

The official Weibo account of The Battle at Lake Changjin published a post to congratulate Ne Zha 2 making new record for Chinese cinema history. This tradition is known as the “Box Office Champion Poster Relay,” originally initiated by Chinese director Xu Zheng (徐峥) in 2015 with the hope of fostering camaraderie and encouragement among filmmakers in China.

On February 6, the official Weibo account of The Battle at Lake Changjin published a post to congratulate Ne Zha 2 making new record for Chinese cinema history.

Earlier in February, Weibo users created the hashtag “The Least Educated Film Star of All Time” (#史上学历最低的影帝#) to celebrate Nezha—a 3-year-old mythological hero.

With the combined success of Nezha 1 and Nezha 2, they jokingly call Nezha the ‘youngest character’ to ever surpass the 10-billion-yuan box office milestone.

One popular comment said:

“Congratulations! The least educated film star in history (didn’t even finish kindergarten), and the youngest one to hold a 10-billion-yuan box office record, is our darling little Nezha.”

Nezha 2 is directed by Yang Yu (杨宇), also known as Jiaozi (饺子), and co-produced by Coco Cartoon (可可豆动画), Coloroom Pictures (彩条屋影业), and others. Released during the Spring Festival holiday, the film continues the storyline from its 2019 predecessor Nezha 1.

Based on Chinese mythology, the film follows the legendary figures Nezha (哪吒) and Ao Bing (敖丙), both characters from 16th-century classic Chinese novel Investiture of the Gods (封神演义). This narrative delves into the history of the Shang (c. 1600-c. 1046 BC) and Zhou (c. 1046-771 BC) dynasties, weaving together folklore, legends, and a variety of mythical beings and creatures.

Nezha and Ao Bing face a dire crisis—their souls remain intact, but their bodies are on the brink of disintegration. To save them, Nezha’s master, Taiyi Zhenren (太乙真人), plans to restore their forms using the mystical Seven-Colored Lotus.

The protagonist, Nezha, is a prominent figure from Chinese mythology and folklore. Besides in Investiture of the Gods, he also appears in Journey to the West (西游记). In Taiwan, Nezha is often revered as the “Third Prince” (三太子, Sān Tàizǐ), as he is the third son of Li Jing (李靖), also known as the Pagoda-Bearing Heavenly King Li (托塔李天王), in these mythological tales.

Ne Zha 2 promo image, China Daily.

Ne Zha 1 and Ne Zha 2 are not the first animated works centered around the character of Nezha.

The 1979 classic film Nezha Conquers the Dragon King (哪吒闹海), produced by Shanghai Animation Film Studio (上海美术电影制片厂), was China’s first large-scale color widescreen animated feature. It depicted Nezha’s conflict with the ‘Dragon King of the East Sea’ (东海龙王) and included the iconic scene where Nezha returns his bones to his father and flesh to his mother. His self-sacrifice in white robes is regarded as one of the most powerful moments in Chinese animation history. With its traditional Chinese aesthetics, this version of Nezha remains a beloved classic, particularly among those born in the 1970s and 1980s.

An important scene of “Nezha Conquers the Dragon King,” where Nezha is about to sacrifice himself to protect the people of Chentang Pass.

For those born in the 1990s and 2000s, childhood memories of Nezha are often linked to the 2003 animated TV series The Legend of Nezha (哪吒传奇), produced by China International Television Corporation. The theme song of this 52-episode series, “Young Hero Nezha” (少年英雄小哪吒), remains a nostalgic tune familiar to many from that era.

The Legend of Nezha

The shared cultural memory of Nezha, along with the overwhelmingly positive reception of Ne Zha 1 in 2019, has undoubtedly laid a strong foundation for the success of Ne Zha 2. Combined with five years of dedicated production—with some one-minute scenes taking up to six months (!) to conceptualize—it seems Ne Zha 2 was destined for cinematic success.

The Evolution of Nezha

Chinese audiences have had a variety of reactions to Ne Zha 2. Many viewers have expressed their love for the film, with some claiming to have watched it multiple times—some as many as six times—in different cinema formats to find the best viewing experience.

Some have found unique interpretations of some of the film’s details. Under various hashtags (e.g. #哪吒2隐喻引热议#), netizens actively discuss and analyze references in the film. These include a dollar sign-like symbol on the celestial artifact Tianyuan Ding (天元鼎) and scenes that seem to allude to the Bretton Woods system, sparking speculation that the film hints at global economic dynamics.

Hidden messages in Ne Zha 2? Some netizens think there are.

Not all feedback has been positive. Some viewers have criticized the film for how it prioritizes traditional values like filial piety in Nezha’s character rather than rebellion, feeling it does not really suit the spirit of his character.

One Weibo commenter (@我不是小日王) wrote:

“I’m not sure if I can say this, but honestly, I don’t really like the changes made to the story line in Nezha 2. In my memory, Nezha was not just the super strong and determined god of the Three Altar Sea Gathering, but also a lonely wanderer. Despite being deeply influenced by Confucian culture, where “filial piety is the greatest virtue” (百善孝为先), he still displayed rebellious behavior going against all morality by returning his flesh to his father and bones to his mother. He’s a genuine pioneer in rejecting patriarchal society (as referenced in Jiang Xun’s Six Lectures on Loneliness). But [in Nezha 2], to make him more relatable to the masses, he is forcibly portrayed as a filial, harmonious, superhero-like little boy.”

The movie’s fighting scenes and the depiction of Nezha as an overly reckless character have also drawn some disapproval. One Weibo user wrote:

“After watching the first film, I thought it was good—a troublemaking demon child defying fate to save the world. After going through so much, you’d at least expect some character growth. But in the second film, he’s still looking for trouble, throwing tantrums whenever he faces difficulties, and howling all the time. I honestly don’t see any charm in his character at all.”

Despite the success of Ne Zha 2, for those who already had a favorite version of Nezha, the changes to the character might be a bit harder to accept.

Beijing Business Newspaper (北京商报) recently posted an overview on Weibo of Nezha’s evolution, suggesting that “every generation has its own Nezha.” From the arrogant deity in the 1961 Havoc in Heaven (大闹天宫) to the defiant rebel in the 1979 Nezha Conquers the Dragon King (哪吒闹海) or the clever and courageous young hero in the 2003 The Legend of Nezha (哪吒传奇), the character has continuously evolved with the times.

From “Small-town Swot” to Stone Diva

It is not only the figure of Nezha that has dominated discussions surrounding Ne Zha 2. Some of the other characters in the film are also resonating with audiences and have become a popular topic of discussion on Chinese social media.

One of the most beloved characters is Shen Gongbao (申公豹). A villain in the first film, Ne Zha 2 adds more depth to his character, leading many viewers to empathize with his struggles.

As a hardworking overachiever with a stutter, not particularly born into privilege like many of the celestial figures in the film, some Chinese netizens suggest that he represents the experience of many “small-town swots” (xiǎozhèn zuòtíjiā 小镇做题家) in China.

Shen Gongbao (申公豹) has become China’s most beloved villain.

“Small-town swot” is a buzzword that has appeared on Chinese social media over the past few years, first popping up on a Douban forum. It refers to students from rural areas and small towns in China who put in immense effort to secure a place at a top university and move to bigger cities. While they may excel academically, even ranking as top scorers, they often struggle to gain social advantages, highlighting a deeper rural-urban divide in China.

Initially used in a self-deprecating manner, the term became a way for people from modest backgrounds to vent their frustrations and self-doubt, eventually striking a chord with many others.

There is now a series of hashtags about Shen Gongbao being a small-town swot (#申公豹 小镇做题家#, #申公豹丑强惨#, #申公豹 真男人#), all adding to the popularity of this character.

Another standout character is Lady Stone (石矶娘娘), a larger-than-life demon whom Nezha must overcome in his celestial trials. She has gained attention for her grand, imposing presence – a bold and diva-like figure who once was a stone.

Lady Stone from Ne Zha 2, and the fan art dedicated to her.

Lady Stone first appears questioning a magic mirror about her beauty, and after being defeated by Nezha, she ultimately accepts her unique form. Some Chinese netizens see her as a challenge to traditional beauty standards, leading to the hashtag “Lady Stone Breaks Beauty Stereotypes” (#石矶娘娘打破白幼瘦审美枷锁#) and countless fan art contributions, celebrating her as a symbol of self-acceptance and female resilience.

The Rise of “Ne Zha Economy”

As the box office success of Ne Zha 2 continues to skyrocket, its economic impact is becoming increasingly evident.

By early February, the film had already generated most of the annual revenue for its production company, Enlight Media (光线传媒). The company’s shares hit an all-time high, soaring over 150% in just six trading days. With box office numbers still rising, Enlight Media’s profits are expected to grow even further, signaling a strong financial outlook.

The film’s success has also had a positive impact on cinema chains. Hengdian Entertainment (横店影视) hit the daily trading limit, while Wanda Film (万达电影) and Bona Film Group (博纳影业) saw their shares rise by over 6%. Other companies in the sector also experienced stock price gains.

Beyond the box office, Ne Zha 2 has driven a surge in related merchandise sales. The film’s characters appear in numerous commercial ads, and Pop Mart’s (泡泡玛特) Ne Zha 2 blind box figurines have been so popular that many stores are down to display items only. Pop Mart’s stock price also hit a new high, significantly boosting its market value.

The Ne Zha 2 blind box figurines from Pop Mart.

In terms of tourism, several regions across China are also looking to capitalize on the film’s popularity. Since Chentang Pass (陈塘关), Nezha’s birthplace in Investiture of the Gods, lacks a clearly defined real-world location, multiple cities are hoping to claim the title of “Nezha’s hometown” (#多地争给哪吒上户口#).

Because Tianjin is a sea city that has a place called “Chentangzhuang”, it already started to promote itself on social media as being Nezha’s birthplace with the hashtag: “Nezha’s Hometown, Tianjin, Invites You to Visit” (#哪吒故里天津喊你来打卡#).

Meanwhile, residents of Chengdu argue that their city is Nezha’s true “home”, since Ne Zha 2 was registered in Chengdu, the director is a native of Sichuan, and the production team, Coco Cartoon, is based in Gazelle Digital Cultural and Creative Valley located in Chengdu’s Tianfu Software Park.

The film is undeniably a “Chengdu-made” production, with elements of Sichuan culture woven throughout, from Taiyi Zhenren’s Sichuan-accented Mandarin to the two Boundary Beasts that look like the bronze masks of Sanxingdui, and the bamboo chairs, covered tea bowls, and flying eaves of Sichuanese architecture in Chentang Pass.

The appearance of two Boundary Beasts (结界兽, Jie2 Jie4 Shou4) is inspired by the bronze masks of Sanxingdui.

For cities with no claim to Nezha’s birthplace, local tourism campaigns have instead spotlighted Nezha temples as must-visit attractions.

How ‘International’ is Ne Zha’s Global Success?

What’s still in store for Ne Zha 2? The Chinese film industry analytics platform Maoyan predicts that the final box office earnings for Ne Zha 2 in mainland China could reach 16 billion yuan ($2.2 billion).

If this figure becomes a reality, the film wouldn’t just be the highest-grossing animated movie—it would also rank among the top five highest-grossing films in global box office history.

But how much of its box office success is truly global? Outside of China, Ne Zha 2 began its international release in mid-February 2025, with a limited release in markets like the United States, Australia, and New Zealand.

By February 20, Deadline reported that $1.72 billion of its earnings came from China alone, indicating that the vast majority of its box office revenue is domestically driven.

However, if anyone questions the significance of the international market’s contribution to Ne Zha 2’s success, they might receive a response similar to that of Wu Jing (吴京), director of the Wolf Warrior (战狼) series. When faced with skepticism about Wolf Warrior 2 making it into the top 100 global box office hits despite 99% of its earnings coming from mainland China, he simply replied:

“So what? That’s still money” (#所以呢 不是钱吗#).

By Wendy Huang

Follow @whatsonweibo

With contributions from Manya Koetse and edited for clarity

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

China Digital

From Weibo to RedNote: The Ultimate Short Guide to China’s Top 10 Social Media Platforms

Weibo, Wechat, Douyin, or Xiaohongshu? Understanding China’s top 10 social media platforms.

Published

1 week agoon

February 18, 2025

WHAT’S ON WEIBO CHAPTER: 15 YEARS OF WEIBO

From Weibo to WeChat, from Rednote to Bilibili, China has a unique social media landscape that is constantly evolving with the times. In this short guide to China’s social media apps, we list the top 10 most popular platforms, explaining their names, origins, and the key features that have made them successful—some of them thriving for over 25 years (!) already.

These are complicated times for social media, as users around the world are jumping between different services while holding different views on what platforms should stand for, how they should be managed, and what their role should be.

In 2025, international media are more focused on Chinese social media apps than ever before, especially after January’s “Tiktok refugee” hype in which waves of US TikTok users migrated to to China’s Xiaohongshu app.

This foreign focus on China’s online landscape also highlights lingering misconceptions, with major media outlets still trying to label Chinese apps as “the Chinese Instagram,” “the Chinese Facebook,” and so on.

Some of these labels made sense around 2010, when Chinese companies were indeed creating domestic equivalents of Twitter or Pinterest. But those apps have since evolved into something much bigger.

Over the past month, we’ve been focusing on ‘15 years of Weibo‘ for our What’s on Weibo Chapters (check out our deep dive here and the expert insight here). The story of Weibo is an example of how China’s online landscape is constantly changing, even though some major social apps are already 15, 20, even 25 (!) years old. Their secret? It’s not copying Western apps—it’s avoiding a cookie-cutter approach and embracing change. As Xiaohongshu’s Charlwin Mao (毛文超) puts it: “We don’t ask ourselves if we’re a social or commerce company—we ask, what does the consumer want?”

Xiaohongshu is no Chinese Instagram. It also wasn’t a shopping site that added reviews—it was a review site that added shopping, completely flipping traditional e-commerce models on its head. One of China’s top livestreaming apps, Kuaishou, didn’t even start as a livestreaming platform. It began as a GIF-making tool, built its user base through other platforms, then evolved into a short-video app before taking off during the livestreaming boom. Today, the company is a major player in generative AI—its Sora competitor, Kling, was born from this adaptability.

These Chinese apps have become superapps by thinking outside the box, refusing to be confined by labels, and evolving like chameleons—adapting their functions to user needs.

In these rapidly changing social media times, I thought it was high time for a short “China Social Media for Dummies” guide. This short guide breaks down the top 10 Chinese social media platforms, what they stand for, and their core features.

For this article, I have selected ten platforms or apps that are generally the most well-known in China and have the highest number of monthly active users. While the first eight social media platforms are undoubtedly the biggest eight, the ranking becomes less clear beyond that. China has a diverse range of social apps across various categories, including dating, gaming, and livestreaming. In this case, I’ve chosen the apps that are the most widely recognized in the mainstream digital landscape.

Content:

1. WeChat (微信) ⎮ “It’s a Way of Life”

2. Douyin (抖音) ⎮ “Record a Beautiful Life”

3. Weibo (微博) ⎮ “Discover New Things, Anytime, Anywhere”

4. Tencent’s QQ (腾讯QQ) ⎮ “Relax and Be Yourself”

5. Kuaishou (快手) ⎮ “Embracing Every Way of Life”

6. Bilibili (B站) ⎮ “( ゜- ゜)つロ Cheers~”

7. Xiaohongshu (小红书) ⎮ “Your Guide to Life”

8. Zhihu (知乎) ⎮ “When There’s a Question, There’s an Answer”

9. Douban (豆瓣) ⎮ “Record Your Book, Film & Music Life”

10. Baidu Post Bar (百度贴吧) ⎮ “Discuss Your Interests, Join Tieba”

1. WeChat (微信)

🚀 Launched: January 2011 by Tencent

🀄 Chinese name: 微信 Wēixìn, literally meaning “micro message.”

💬 Tagline:”微信,是一个生活方式”

“WeChat, it’s a way of life”

🔍 WeChat at a Glance:

WeChat is one of the most famous Chinese apps and is the national multifunctional ‘superapp.’ It was developed by Tencent, a social-focused tech giant that has proven its ability to understand what Chinese internet users want. Tencent has been successful in the social networking and online gaming markets since the early 2000s, and WeChat is a product of strategies it developed between the late 1990s and early 2010s. WeChat (Weixin) was an instant hit. Within a year of its launch, it already had 100 million users. By January 2013, the number had reached 300 million. Today, WeChat has over 1.38 billion monthly active users, making it the most popular app in China.

More than just a social media platform, WeChat has become a digital key to navigating daily life in China. It is hard to label this app as anything other than a ‘superapp,’ as through the years it has added so many functions that it has become one of China’s most versatile platforms. It serves as a business card, payment method, news reader, and marketing platform. For personal users, WeChat is the go-to tool for staying in touch with friends and family. For brands and businesses, it is an essential tool for building and maintaining relationships with consumers.

🔑 Some Key Features of WeChat:

● Messaging (消息): Text and voice messaging, voice and video calls, group chats (up to 500 people), file transfers (videos/documents/images), gift-giving, sending red envelopes, built-in translation, and extensive use of emojis and stickers.

● Moments (朋友圈): WeChat’s social feed, where users can share photos, videos, and updates with friends—like a private social network.

● WeChat Pay (微信支付): Digital wallet for mobile payments in both online and offline purchases. WeChat is also expanding its palmprint payment services, allowing users to pay through palm recognition scannning technology for their cashless transactions.

● WeChat Official Accounts (公众号): Allows users to follow brands, news, and services for updates, acting as a hub for business and content distribution.

● Mini Programs (小程序): Embedded lightweight apps within WeChat, offering services like food delivery, ride-hailing, shopping, and games, eliminating the need for separate app downloads.

● WeChat Channels (视频号): A short-video and livestreaming feature within WeChat, allowing users to create, share, and discover video content.

🌍 Global Influence:

WeChat is one of the most popular messaging apps in the world (although it is banned in India). WeChat and Weixin are not just different names for the same app—they have distinct functionalities. WeChat serves the international market, while Weixin is designed for the Chinese market. The two versions are distinguished by mobile numbers and operate on separate servers. One key difference is official accounts: Weixin users may not be able to search for or subscribe to official WeChat accounts available to overseas users.

📌 Important to know:

WeChat launched its QR code payments (二维码支付) in 2012, a year after Alipay. With the rise of smartphones, QR code payments made digital transactions accessible to everyone, from store owners to street vendors. WeChat’s popularity played a key role in transforming China from a predominantly cash-based society in the early 2000s to a cashless society by the late 2010s (Ghose 2024).

2. Douyin (抖音)

🚀 Launched: September 2016 by Bytedance

🀄 Chinese name: 抖音 Dǒuyīn, literally meaning “shaking sound.”

💬 Tagline: 记录美好生活

“Record a Beautiful Life”

🔍 Douyin at a Glance:

Douyin is the Chinese mainland version of the globally popular app TikTok and the country’s most popular short-video platform. From the beginning, its parent company, ByteDance (字节跳动), founded in 2012 by Zhang Yiming (张一鸣), focused on two core elements: building innovative apps and using the power of AI for content personalization. Before launching Douyin, ByteDance had already found success with Toutiao (今日头条), a highly popular news aggregator app also relying on AI-powered content personalization. Although Douyin’s focus on music, influencer culture, and short, creative videos is quite different from Toutiao’s, its success has been largely built on the recommendation systems and operational expertise ByteDance had developed through Toutiao. Before building Toutiao, Zhang Yiming worked at Microsoft, among other companies, and co-founded the real estate search engine 99fang.com.

kuaishou

Beyond ByteDance’s expertise, Douyin thrived thanks to China’s advanced 4G/5G infrastructure and a booming e-commerce industry. While Douyin initially focused on user-generated entertainment content, it has gradually evolved into a powerful multi-functional platform where users also consume and discuss the latest news and current events.

Today, Douyin and Weibo are among the most influential social platforms in China for following and discussing breaking news. Douyin is more influential in terms of active users: there are more than 760 million active monthly users (Brennan 2020; Su 2024).

🔑 Some Key Features of Douyin:

● Follow (关注): Similar to Weibo and Xiaohongshu, Douyin operates on a follower-followee network model, where users can follow others without requiring mutual follow-backs. Not every Douyin user creates videos; many are solely viewers.

● Short Video Creation (快拍): Douyin’s primary function is short video creation, either by filming directly in the app or uploading pre-recorded content from the phone’s gallery.

● AI Templates and Filters (AI创作): Douyin offers a vast range of AR filters, stickers, and special effects to make videos more attractive, fun, or engaging.

● Live Streaming (直播): Users can host live streams, interact with viewers in real time, and receive virtual gifts that can be converted into real-world earnings.

● Front Page (首页): The endlessly scrollable front page features personalized content recommended by AI algorithms based on the user’s profile, location, preferences, and interactions.

● Friends (朋友): Users can import contacts from WeChat or QQ and see their videos directly within the app.

● Private Messaging (消息): Douyin supports private direct messaging with group chat options for private conversations and social interactions.

● Douyin Trending Lists (抖音热搜): Users can explore trending topics and hot searches. These lists are segmented into categories such as live streaming, films, brands, and music, offering insights into what’s currently popular.

● Douyin Mall (抖音商城): Douyin’s in-app e-commerce platform, which delivers a personalized shopping experience by recommending products based on user data and preferences.

🌍 Global Influence:

It is clear that ByteDance has significant international ambitions—and with great success. No other Chinese digital product has conquered the global market in the same way as TikTok, the international version of Douyin. In 2017, ByteDance acquired the app Musical.ly, which was already popular in the U.S. and Europe, in a strategic move to rapidly integrate TikTok into the Western market. Today, TikTok boasts over 1.5 billion users worldwide. However, the app’s global influence is not without controversy. TikTok has been banned in India, and since 2020, plans to ban it in the United States have repeatedly surfaced. TikTok sits at the center of geopolitical tensions between the U.S. and China, symbolizing broader concerns about China’s growing technological power and influence.

📌 Important to know:

TikTok and Douyin are similar in many ways, but they are two separate apps. Douyin is not available in foreign app stores like Google Play or the international Apple Store, while TikTok is not available in Chinese app stores. The apps feature different content and different popular creators. Content moderation on the two platforms also differs significantly. Internationally, TikTok’s moderation follows practices similar to other global platforms, with rules on hate speech, harassment, nudity, and other forms of inappropriate content. In contrast, Douyin adheres to strict Chinese internet regulations and censorship laws, enforcing different and much broader rules on what can be posted. These differences, along with varying cultural norms and regulatory environments, have transformed Douyin and TikTok into two distinct platforms in terms of content and user experience.

3. Weibo (微博)

🚀 Launched: August 2009 by Sina

🀄 Chinese name: 微博 Wēibó, literally meaning “micro blog.”

💬 Tagline: 随时随地发现新鲜事

“Discover new things anytime, anywhere”

🔍 Weibo at a Glance:

Weibo launched in 2009 as a Chinese equivalent of Twitter but quickly evolved into much more—a uniquely Chinese, versatile, and dynamic platform where users follow celebrities, media influencers, and stay up to date on the latest news. Over the past fifteen years, Weibo has become China’s primary digital space for public discourse on unfolding events. Even today, despite a more decentralized social media landscape in China, Weibo remains China’s online ‘living room’ where people follow and discuss news and entertainment, and the platform still has about 580 million monthly active users. To learn all about Weibo’s journey, check out our detailed report here.

🔑 Some Key Features of Weibo:

● Follow (关注): Unlike friend-based systems like Facebook or WeChat Moments, Weibo operates on a follower-followee model: users can follow others without requiring mutual follow-backs. This also means that some celebrities, such as Xie Na (谢娜), have accumulated over 120 million followers throughout the years.

● Microblogging (发微博): The core feature of Weibo is posting short messages, which can include videos and images. Initially limited to 140 characters, users can now post up to 5,000 Chinese characters. If longer than that, users can change a post into a separate blog article.

● Hot Topics (微博热搜): Weibo provides trending topic lists, hashtags, and rankings of popular influencers across different categories—from general hot lists and headlines to more niche areas such as entertainment, gaming, movies, sports, and more. This feature helps users stay up to date with the latest trends in their fields of interest.

● Video (视频): A video-only feed curates hot videos based on algorithms, comparable to YouTube Shorts or TikTok.

● Super Topics (超级话题): These are niche communities dedicated to specific interests, similar to subreddits. (Read more here.)

● Private Messaging (消息): Weibo supports private direct messaging with group chat options.

🌍 Global Influence:

Weibo is not very international. Although the platform allows international users to register, only a limited number of countries can do so based on their phone numbers. Eligible countries include Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Thailand, India, the UK, USA, Spain, Italy, Germany, and a few others. Meanwhile, many countries are excluded—such as nearly all Northern European and African nations, along with most countries in South America. Despite these restrictions, Weibo remains a key platform for foreign entities engaged in China-focused marketing or diplomacy. As a result, most foreign embassies in China maintain official Weibo accounts, as do tourism bureaus, international brands, and major global celebrities, including actors, athletes, and DJs.

📌 Important to know:

Although trending topics on Weibo are often related to entertainment, society, and news events, Weibo is also highly Weibo-focused. Many of its trending topics originate on the platform itself—such as viral comments, new features or guidelines, celebrities’ posts, or Weibo-related events and contests (Weibo, as a company, frequently organizes and sponsors events ranging from entertainment to sports). This has created a distinct Weibo culture, more reminiscent of Western platforms like Reddit than X/Twitter or Facebook.

4. Tencent’s QQ (腾讯QQ)

🚀 Launched: February 1999 by Tencent

🀄 Chinese name: QQ: “Q” and “QQ” are also used for “cute.”

💬 Tagline: “轻松做自己”

“Relax and be yourself”

🔍 QQ at a Glance:

QQ has always been known as China’s most powerful instant messaging software. It is also one of China’s oldest social media platforms, and in many ways, its success paved the way for WeChat to thrive. Launched by Tencent in 1999 under the name OICQ, this instant messaging service was China’s counterpart to the Israeli software ICQ, developed in 1996 and later acquired by AOL. Following a lawsuit from AOL, Tencent rebranded the application as QQ. As the platform partnered with pager services and mobile communication companies, QQ was initially used on pagers, personal computers, and for SMS services. Over time, QQ evolved and is now primarily used on smart mobile devices. In 2005, Tencent introduced QZone (QQ空间), a social media platform integrated with QQ, where users can share updates, photos, videos, and more with friends.

For many people, QQ is a nostalgic part of their childhood—comparable to MSN Messenger in the West. As WeChat rose in popularity, many users migrated to it, particularly since Tencent made it easy to import all QQ contacts into WeChat. Despite this shift, QQ remains actively used, especially among young people and fans of ACG (anime, comics, and games), as well as older users who rely on it for work-related purposes such as file sharing and communication. In fact, according to Tencent’s 2024 financial report, QQ’s mobile monthly active users still reached 554 million, demonstrating its lasting influence in China’s social media landscape even after 25 years (Negro et al 2020; Yidong Huliangwang 2024)

🔑 Some Key Features of QQ:

● Messaging (消息): Text and voice messaging, voice and video calls, group chats, and customizable profile styles, chat decorations, and themes.

● Groups (QQ群): QQ Groups are like chatrooms for users with shared interests, managed and guided as community spaces.

● File Management/Online Storage (文件传输): Group file sharing, large file uploads, and permanent file storage—unlike WeChat, QQ stores files permanently and can handle larger files.

● Mail (QQ邮箱): An email service hosted by QQ.

● Wallet (QQ钱包): Top up phone credit, pay off credit card bills, and settle utility fees for water, electricity, and gas.

● Super QQ Show (QQ秀): A customizable avatar feature where users can dress up and design their online persona which can be used across QQ-related platforms, using accessories that can be purchased with QQ Coins (QQ币).

● QQ Games (QQ游戏): Access and play games directly within the app or through linked gaming platforms.

🌍 Global Influence:

QQ is very much a domestic app. It’s not particularly easy for foreigners to register either. If you use a foreign phone number, verification messages often fail to arrive, or the app may flag your number as “suspicious” or “not secure.” If you use a Chinese phone number, registration requires a Chinese name and ID number. While there are certainly foreigners on QQ, it’s clear that making the app more foreigner-friendly is not a priority for Tencent.

📌 Important to know:

Besides its file transfer feature, QQ’s group function is also quite popular, offering much larger group capacities compared to WeChat. QQ Groups cover a wide range of topics, from web novels to cryptocurrency, attracting communities of all kinds. Depending on the group type, VIP members can create groups with up to 2,000 members, while certified members can host groups with up to 5,000 members. In the past, QQ Groups have faced backlash for hosting vulgar or inappropriate content, leading to hefty fines for Tencent and increased moderation efforts.

5. Kuaishou (快手)

🚀 Launched: March 2011, but under different name (GIF快手) as a GIF-making tool.

🀄 Chinese name: 快手 Kuàishǒu, literally meaning “fast hand.” Its international name is “Kwai.”

💬 Tagline: 快手,拥抱每一种生活

“Kuaishou, embracing every way of life”

🔍 Kuaishou at a Glance:

China has many different apps for sharing videos and livestreaming, but Kuaishou holds a unique place in this crowded digital landscape. Why? Unlike most other popular social apps in China, Kuaishou’s content and user base are deeply rooted in the country’s smaller towns and rural areas—over 60% of its users come from rural communities. As a result, Kuaishou has become the go-to app for content related to authentic rural lifestyles and agriculture, setting it apart from apps like Douyin or Xiaohongshu, which primarily cater to urban, middle-class users in higher-tier cities (Ran 2024, 3). Kuaishou’s success story (the app has around 500 million monthly active users) reflects that of many other Chinese digital giants—it has evolved with the times, continuously adapting to user needs instead of following a cookie-cutter approach or a ready-made formula.

Launched in 2011 as a GIF-making tool during Weibo’s golden era, the platform later transformed into a short-video app.Founded by Su Hua (宿华) and Cheng Yixiao (程一笑), Kuaishou benefited from strong technical expertise. Before co-founding the platform, Su worked as a software engineer at both Google and Baidu. Kuaishou’s major mainstream breakthrough came in 2016, when it introduced livestreaming, which quickly became a core part of the platform. Since 2020, the platform has focused more on e-commerce and has integrated it into the app in various ways, making it an appealing option for rural merchants and aspiring influencers. By 2021, half of all rural creators on Kuaishou were generating income from the platform (Ran, 2024, 1).

🔑 Some Key Features of Kuaishou:

● Short Video Feed (短视频): Kuaishou’s main function is sharing and scrolling through short videos, covering everything from gaming and cooking to news events and memes. Through the app’s “Discovery” (发现) feature, you can find new creators and follow more people.

● Live Streaming (直播): Kuaishou offers a wide range of livestream channels available at all hours, from gaming to e-commerce, often blending shopping and entertainment.

● Special Filters: Like Douyin or Snapchat, Kuaishou provides a variety of video effects and templates so that users can post creative videos.

● Kuaishou Shop (快手小店): Kuaishou’s in-app e-commerce platform offers a wide selection of products, including household items, food, and cosmetics.

● Kuai Coins (快币): Kuaishou users can top up their accounts with ‘Kuai Coins’ (Kuaibi), the platform’s virtual currency. These can be used to purchase virtual gifts to support content creators or unlock paid content.

🌍 Global Influence:

Within mainland China, Kuaishou’s strength lies in its focus on second- and third-tier cities as well as rural areas, meaning it is not necessarily focused on expanding its global influence with this particular app. However, similar to the domestic vs. foreign approach of Douyin and TikTok, Kuaishou released an international version of its app called Kwai, though it did not achieve the same level of success as TikTok. Another Kuaishou product with a much greater international impact is its self-developed video generation model, Kling (可灵), also known as KLING AI. Initially, Kling started as a feature within Kuaishou’s video editing app, KuaiYing (快影), in China but was later launched internationally, gaining recognition as a powerful AI model and a possible alternative to OpenAI’s Sora.

📌 Important to know:

Kuaishou is known for increasing its market share by partnering up with other powerful platforms or brands. For example, the company has partnered with Chinese shopping/food delivery platform Meituan since 2021 in the local life services sector. For its e-commerce livestreaming, Kuaishou previously joined forces with JD.com. To drive more traffic to its platform, Kuaishou also established partnerships for copyright and content with various international sports events, including the NBA and the UEFA Champions League, as well as the Tokyo and Paris Summer Olympics, along with the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics and the 19th Asian Games Hangzhou.

6. Bilibili (B站)

🚀 Launched: June 26, 2009 by Xu Yi (徐逸)

🀄 Chinese name: 哔哩哔哩 Bìlī Bìlī, doesn’t really mean anything but sounds cute and vibrant, like beep beep. Bilibili is more commonly referred to as “B站,” meaning “B-station.”

💬 Tagline: (゜-゜)つロ干杯~-bilibili

“Cheers to Bilibili” [not literally, but that’s what this symbolic motto conveys]

🔍 Bilibili at a Glance:

Bilibili is China’s online home for fans of anime, comics, games (ACG), and technology. While the video streaming platform started as a niche community, it has since grown into one of the go-to video-sharing platforms for China’s Generation Z. Founder Xu Yi (徐逸) designed the earliest version as an improved alternative to existing video-sharing platforms, particularly the ACG hub ACfun (also known as A站, A-station). Although Bilibili remains heavily centered on anime, music, esports, and gaming culture, the platform now hosts a vast range of content, with creators covering topics such as culture, education, and social commentary. Bilibili allows both amateur and professional creators/channels to upload content, as well as producing in-house content, making it a diverse and dynamic platform where users can find everything from unpolished vlogs to Chinese anime series or BBC and History Channel documentaries. This has led to “B Station” becoming a versatile platform used by some 348 million users on a monthly basis. A unique aspect of Bilibili is its user engagement system. One way the platform helps maintain content quality is by requiring users to first answer a set of questions before posting comments and videos. Official members can also go through six membership levels, each unlocking various platform privileges, fostering a stronger sense of community and rewarding user engagement.

🔑 Some Key Features of Bilibili:

● Home of Video Streaming (首页): On Bilibili’s main page, users can explore the latest trending videos or discover new content across various categories, from anime series (番剧) to entertainment (娱乐) and music (音乐).

● Bullet Comments (弹幕评论): Bullet comments, or danmu, are real-time floating texts overlaid on videos, creating an interactive and communal viewing experience. Bilibili was the first Chinese platform to adopt this feature, which has since become its signature function.

● Livestreaming (直播): Users can browse Bilibili’s livestreaming rooms, where they’ll find a variety of live gaming streams, as well as study sessions, homework help, and other interactive content.

● Bilibili Game Center (游戏中心): A platform for game distribution, reviews, and gameplay videos, covering both mobile and PC gaming content.

● Bilibili Manga (哔哩哔哩漫画): A section dedicated to reading and discussing manga, including licensed and original works.

● Bilibili Classroom (哔哩哔哩公开课): Educational content featuring tutorials, lectures, and courses on a wide range of topics.

● Bilibili Shopping (会员购): An integrated e-commerce section where Bilibili members can purchase merchandise, anime goods, and other products related to content creators and the Bilibili platform.

🌍 Global Influence:

Since Bilibili is focused on ACG, it has some niche global appeal among those interested in anime, gaming, and East Asian pop culture. However, beyond these communities, its global influence remains quite limited. In addition to being primarily geared toward Chinese-speaking users, much of the platform’s content is also subject to copyright restrictions outside of China, making it difficult or even impossible for many international viewers to access professional channels on the site.

📌 Important to know:

Like Weibo, Bilibili is a company that focuses on building communities and fostering a unique “Bilibili Culture.” Since 2010, Bilibili has been the main initiator, host, and/or sponsor of various popular events, most famously its Bilibili Spring Festival Gala. Additionally, Bilibili actively contributes to the growth of the Chinese anime industry by financing and co-producing anime content while also making efforts to distribute Chinese anime globally.

7. Rednote/Xiaohongshu (小红书)

🚀 Launched: June 2013 by Charlwin Mao (毛文超) and Miranda Qu (瞿芳)

🀄 Chinese name: 小红书 Xiǎohóngshū, literally meaning “Little Red Book.”

💬 Tagline: 你的生活指南

“Your Guide to Life”

🔍 Xiaohongshu at a Glance:

Is it Xiaohongshu, Rednote, or RED? In China, there is actually only one name for this “little red app”: Xiaohongshu. The Shanghai-based platform began as an online international “shopping guide” where users posted independent reviews (videos, text, images) of luxury products and cosmetics they had purchased. Over time, it evolved into a broader lifestyle community focused on travel, fitness, fashion, and overseas experiences. As the app gained popularity, the products reviewed by users also started being distributed through the platform itself—flipping the traditional e-commerce model on its head. Instead of a shopping site with reviews, Xiaohongshu became a review site that seamlessly integrated e-commerce. “We don’t ask ourselves if we’re a social or a commerce company,” Xiaohongshu co-founder Charlwin Mao once said: “We ask, ‘what does the consumer want?’” (Rowan 2016).

By 2025, Xiaohongshu’s influence is undeniable. With over 300 million monthly active users, the majority of whom are young, urban, and female, it has become an essential part of China’s online ecosystem. What sets Xiaohongshu apart is its ability to blend genuine real-life experiences with online sharing and offline consumption, creating a truly unique digital space.

🔑 Some Key Features of Xiaohongshu:

● Discover (发现): the core function of Xiaohongsu is the personalized homepage (首页), where users can discover new user-generated content, either based on interest through data-driven algorithms, or based on location, giving an overview of content that was posted near to you.

● Post a Note (发布笔记): All users can create content Xiaohongshu and post either videos, images, text, writing reviews, sharing tips, or document experiences. In doing so, they can tag products and link directly to e-commerce listings.

● Shopping (购物): Xiaohngshu is both a social app and a shopping plaform: users can browse and buy products without leaving the app. The stores selling the products can also be ‘followed’ to stay in touch.

● Live Streaming (直播): Xiaohongshu has a livestream feed, where users can scroll through thousands of different livestreams happening simultaneously. These streams range from people singing and teaching English to selling products, cooking, or giving makeup tutorials.

🌍 Global Influence:

Since much of its content has always revolved around overseas shopping experiences, Xiaohongshu has been inherently global from the start, catering primarily to overseas Chinese users. As a result, the app has been available in foreign app stores and allowed international users to sign up. However, nobody expected Xiaohongshu to become a global sensation overnight in January 2025. With a potential TikTok ban looming in the U.S., millions of American TikTok users began seeking alternative platforms. The most notable destination for these users was Xiaohongshu/Rednote, which saw a massive influx of so-called “TikTok refugees” (TikTok难民). This sudden surge propelled Xiaohongshu to the #1 spot in app stores across the U.S. and beyond. The arrival of over three million foreign users marked an unprecedented milestone for a domestic Chinese app, bringing Xiaohongshu into the global spotlight. Though not all of these TikTok users may stay long-term, and TikTok wasn’t banned after all, the event cemented Rednote’s instant fame. In response, the platform has taken proactive steps to internationalize, including hiring foreign content moderators and launching a one-click translation feature for seamless cross-language interaction.

📌 Important to know:

Gender demographics inevitably play a role on all social media platforms, but this holds especially true for Xiaohongshu, as its user base is overwhelmingly female—approximately 80% of its users are women, while only about 20% are men. This is very different from platforms like Bilibili or Zhihu (which have more male users) or WeChat, where gender demographics are more balanced. Since the platform is targeted toward educated, wealthier, and predominantly female users, its content naturally reflects these demographics. When combined with its strong e-commerce aspect, Xiaohongshu stands out as a unique platform that is far more about lifestyle, shopping, and real-life experiences than it is about politics, economics, or news events.

8. Zhihu (知乎)

🚀 Launched: January 26 2011, with funding from, among others, Tencent and Sogou.

🀄 Chinese name: 知乎 Zhīhū, which is usually left untranslated, but with 知 (zhī) meaning knowledge and 乎 (hū) serving as a classical particle for a question or emphasis, the meaning could be loosely translated as “Do you know?”

💬 Tagline: 有问题,就会有答案

“When there’s a question, there’s an answer”

🔍 Zhihu at a Glance:

Zhihu is most commonly known as the Chinese version of the American question-and-answer website, Quora. While Quora was founded in 2009, Zhihu was launched in 2011 and has been growing steadily ever since. It is recognized for its relatively high-level discussions, often focusing on topics such as society, economy, business, history, law, and many other areas. Users can submit both questions and answers, with the best answers being upvoted and placed at the top of the thread. Some popular contributors have answered thousands of questions, with many responses resembling mini-essays. Zhihu has over 80 million monthly active users. Unlike many other Chinese social media platforms, it has a slight majority of male users (51.5%), with most of its users being highly educated. (Bao 2024, 1).

🔑 Some Key Features of Zhihu:

● Q&A: The core function of Zhihu is either posting a question (提个问题) or replying to a question (回答问题).

● Zhihu Homepage (首页): On the main homepage, users get an overview of recommended posts. They can also select from various categories—ranging from science to law—and view the most popular posts across different topics.

● Live Streaming (直播): Zhihu offers a livestreaming feature, where users can scroll through livestreams and post reactions or questions in real time.

● Zhihu Direct Answer (知乎直答): Zhihu has also introduced the “Zhihu Direct Answer” AI model, which integrates the DeepSeek-R1 model to allow users to ask questions and receive direct answers through a chatbot.

● Zhihu Podcast Square (播客广场): Zhihu’s opodcast squore’ is a place where Zhihu users can listen and subscribe to podcasts.

🌍 Global Influence:

Unlike many other Chinese apps, Zhihu is available on foreign app stores, such as Google Play, and allows users from a wide range of countries to sign up. Nevertheless, the platform remains primarily China-focused, with Chinese as the main language. While Zhihu is popular among overseas Chinese communities, it lacks significant global influence.

📌 Important to know:

In the AI era, where chatbots can quickly provide direct answers to almost any question, traditional question-and-answer platforms risk losing relevance. Zhihu, however, is using AI tools to its advantage by integrating an AI-powered search function and a DeepSeek-based chatbot to handle straightforward queries. By doing so, Zhihu is positioning itself as the go-to platform for reliable answers and diverse perspectives offered by both authentic users and AI.

9. Douban (豆瓣)

🚀 Launched: March 2005

🀄 Chinese name: 豆瓣 Dòu Bàn, literally means the “cotyledon of a bean” but the platform was actually named after a Beijing hutong (traditional alley) (Shen 2019).

💬 Tagline: 来豆瓣,记录你的书影音生活

“Come to Douban, record your book, film & music life”

🔍 Douban at a Glance:

Douban is China’s online home of books, music, movies, and more. The site has been around for two decades already, and thus was originally very much desktop-based. While Douban is primarily a review site, it has evolved into a vibrant online community of “Douban friends” (豆友们), where users can explore and discuss the latest films, connect with people who share similar interests, look up events, and seek advice on anything from work-related problems to love and relationships. Douban has approximately 60 million monthly active users and a much larger base of about 200 million registered users. Most importantly, it’s the go-to platform for checking the latest ratings and reviews on blockbuster movies and highly anticipated TV dramas.

🔑 Some Key Features of Douban:

● Movie Reviews and Ratings (豆瓣电影): ‘Douban Movie’ is one of Douban’s core features. Similar to IMDb, it enables users to explore reviews, blogs, and ratings for the latest films, discuss trending topics in the world of cinema, and search for the highest- or lowest-rated movies.

● Books and Music (豆瓣读书, 豆瓣音乐): In line with ‘Douban Movie,’ these sections offer similar functionalities for books and music, allowing users to post reviews and discover new titles or albums within their favorite genres.

● Groups and Forums (豆瓣小组): Douban Groups allow users to join or create communities centered on specific interests, such as hobbies, professions, or niche topics.

● Event Listings (同城活动): This feature helps users discover upcoming local events, from exhibitions and workshops to concerts and meetups.

● Douban Merchandise (豆瓣豆品): An online shop offering a range of unique products, including bookmarks, notebooks, sweaters, and umbrellas.

🌍 Global Influence:

Douban is open to international users, but with its community-driven approach, it remains heavily China-focused, particularly in its selection of books, movies, and event listings. In the English-language social media space, platforms like Goodreads, IMDb, and Reddit already offer many of the same functions as Douban.

📌 Important to know:

China has an incredibly vibrant TV drama industry. With so many new dramas released every month, many people rely on Douban ratings to decide which ones are worth watching and which they can skip.

10. Baidu Post Bar (百度贴吧)

🚀 Launched: December 2003 by Baidu

🀄 Chinese name: 百度贴吧 Bǎidù Tiēbā: Baidu Post Bar

💬 Tagline: 聊兴趣,上贴吧

“Discuss interests, join Tieba”

🔍 Baidu Tieba at a Glance:

Baidu Tieba is an online social media forum where users can explore various ‘bars’—online groups dedicated to specific topics. As a discussion platform divided into thousands of communities, it is somewhat similar to the American platform Reddit. On Baidu Tieba, people can follow and participate in all kinds of groups, from Beijing-focused ones to parenting groups, specific film and arts groups, or those dedicated to tech or business. There are thousands, even millions, of different topic boards to explore, with each ‘bar’ forming its own community.

In its heyday, Baidu Tieba had around 500 million monthly active users, but this number has decreased over the years. In 2021, there were reportedly only about 37 million monthly active users left (Sanyi Shenghuo). In China’s current social media era, Baidu Tieba might not have done enough to compete with newer and more innovative platforms. Although other platforms, such as the Chinese video livestreaming services Huya (虎牙) or YY (YY直播), likely have a stronger presence in terms of active users, Baidu Tieba remains more well-known because it has been around for so long and has become a household name when it comes to China’s internet.

🔑 Some Key Features of Baidu Tieba:

● Topic-Based Communities (贴吧): The core function of Baidu Tieba is its tieba (贴吧), which are topic boards or discussion-based communities. On the main page, users can explore trending topics across various major communities.

● Live Streaming (直播): Baidu Tieba also features a livestreaming function, allowing users to explore various ongoing livestreams. Many streamers broadcast simultaneously across multiple platforms to maximize their earnings through virtual gifts and monetization.

● Chat Rooms (聊天频道): Baidu Tieba’s communities include dedicated chat channels where members can engage in direct conversations.

● Topic Moderators (吧主): Each topic board has its own moderators (吧主), who are responsible for managing discussions and moderating content within the community.

● AI Square (AI广场): AI Square (AI广场) is a feature within Baidu Tieba that integrates AI-driven interactions across different topic boards. For example, in the parenting community, users can chat with AI-generated “mothers” to seek advice on child-rearing, feeding babies, and other parenting topics.

🌍 Global Influence:

Baidu Tieba is aimed at domestic audiences. Although Baidu as a company has global ambitions and international influence, its worldwide efforts do not extend to Baidu Tieba, which remains a classic representation of China’s Web 2.0 era.

📌 Important to know:

Baidu Tieba is an important part of China’s internet history. Many of the country’s most famous viral trends and memes from the 2005–2010 era originated on Baidu Tieba, which became an influential platform due to its decentralized structure—managed by communities rather than a central authority. Words like “diaosi” (屌丝, loser) and “tuhao” (土豪, filthy rich), both of which remain widely used today, first gained popularity on Baidu Tieba. Although Baidu Tieba has lost its relevance as a leading platform for online discussions in China, its impact on the country’s internet culture continues to this day (Edward Shuo 2024).

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

References

◾ Brennan, Matthew. 2020. Attention Factory: The Story of TikTok and China’s ByteDance. ChinaChannel. https://amzn.to/3X2CEwS

◾ Edward Shuo/Edward说. 2024. “Baidu Tieba from Glory to Decline: Robin Li Abandoned Baidu Tieba [百度贴吧辉煌到没落,李彦宏放弃百度贴吧].” QQ News, August 26. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://news.qq.com/rain/a/20240826A04ZJT00

◾ Ghose, Ronit. 2024. Future Money: Fintech, AI, and Web3. London: Kogan Page.

◾ Negro, Gianluigi, Gabriele Balbi and Paolo Bory. 2020. “The Path to WeChat: How Tencent’s Culture Shaped the Most Popular Chinese App, 1998–2011.” Global Media and Communication 16 (2): 208-226.

◾ Yidong Huliangwang 移动互联网. 2024. “Why Are So Many People Still Using QQ [为什么还有那么多人在用QQ]?” Tencent Research Institute 腾讯研究院, March 27. Accessed February 13, 2025. https://www.tisi.org/27710/.

◾ Ran Xi. 2024. “Rural Chinese Youth on Kuaishou: Performing Gender, Labor, and Rurality.” Journal of Youth Studies, August 19.

◾ Rowan, David. 2016. “China’s $1bn Shopping App Turns Everyone Into Trendspotters.” WIRED Magazine, April. Accessed February 19. https://www.wired.com/story/little-red-book-xiaohongshu-crowdsourced-shopping-app/.

◾ Sanyi Shenghuo 三易生活. 2021. “Baidu Tieba’s User Loss of Nearly 90% in Five Years? The Past Is Gone, Let’s Look at Today—Is Baidu Tieba Exiting the Historical Stage? [百度贴吧五年用户流失近九成?前浪已过且看今朝——百度贴吧要退出历史舞台了吗?]” Jiemian, October 29. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www.jiemian.com/article/6759080.html

◾ Shen, Xinmei. 2019. “How Douban Went from China’s IMDB to Its ‘Spiritual Corner’.” South China Morning Post, October 15. Accessed February 16, 2025. https://www.scmp.com/abacus/who-what/what/article/3100865/how-douban-went-chinas-imdb-its-spiritual-corner.

◾ Su, Chunmeizi. 2024. Douyin, TikTok and China’s Online Screen Industry: The Rise of Short-Video Platforms. London & New York: Routledge.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

What’s on Weibo Chapters

Subscribe

The Unstoppable Success of Ne Zha 2: Breaking Global Records and Sparking Debate on Chinese Social Media

From Weibo to RedNote: The Ultimate Short Guide to China’s Top 10 Social Media Platforms

Collective Grief Over “Big S”

Tuning Into the Year of the Snake

The ‘China-chic Girl’ Image and the Realities of China’s Competitive Food Delivery Market

Our Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Why Chinese Hit Movie “Her Story” is ‘Good Stuff’: Stirring Controversy and Celebrating Female Perspectives

Chiung Yao’s Suicide Farewell Letter: An English Translation

12-Year-Old Girl from Shandong Gets Infected with HPV: Viral Case Exposes Failures in Protecting Minors

Breaking the Taboo: China’s Sanitary Pad Controversy Sparks Demand for Change

Weibo Watch: Christmas in China Is Everywhere and Nowhere

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

Weibo Watch: China’s Online Feminism Is Everywhere

Story of Chinese Female MA Graduate Going Missing for 13 Years Sparks Online Storm

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight10 months ago

China Insight10 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music11 months ago

China Music11 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Insight12 months ago

China Insight12 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Digital9 months ago

China Digital9 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI