China Digital

Here’s Xi the Cartoon – Online Animations Are China’s New ‘Propaganda Posters’

Easy to click, view & share – short cartoons and gifs are the propaganda posters of China’s new digital era.

Published

7 years agoon

PREMIUM CONTENT ARTICLE

In an era where China’s young generations are practically glued to their smartphone screens, China’s propaganda departments are stepping up their game. Online animated videos and gifs use bright colors, simple design, and a very likable Xi to deliver strong political messages.

The speech that was delivered by president Xi Jinping at the APEC summit last week made its rounds on Chinese social media this Tuesday – not as a video, but as an animated cartoon.

The APEC Economic Leaders’ Meeting took place in Vietnam’s Da Nang from November 10-11, and was attended by international world leaders such as Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, American President Donald Trump, and South Korean President Moon Jae-in.

As one of the keynote speakers to the APEC CEO summit, Xi talked about his views on the Asian region’s future. The speech was especially momentous since it marked Xi’s first public address at an international multilateral meeting since the conclusion of the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China.

In his address, Xi spoke about China’s commitment to regional multilateralism and open economic globalization, and the importance of promoting inclusive development.

The animated cartoon version of the speech presents China as a leader in the region, with Xi as the main cartoon character. It was widely shared on Chinese social media by state media outlets for the past few days, at a time when cartoons and gifs seem to have become the new way of communicating Xi’s important visits and speeches to the online population.

Xi’s Animated Speech: China Leads the Way

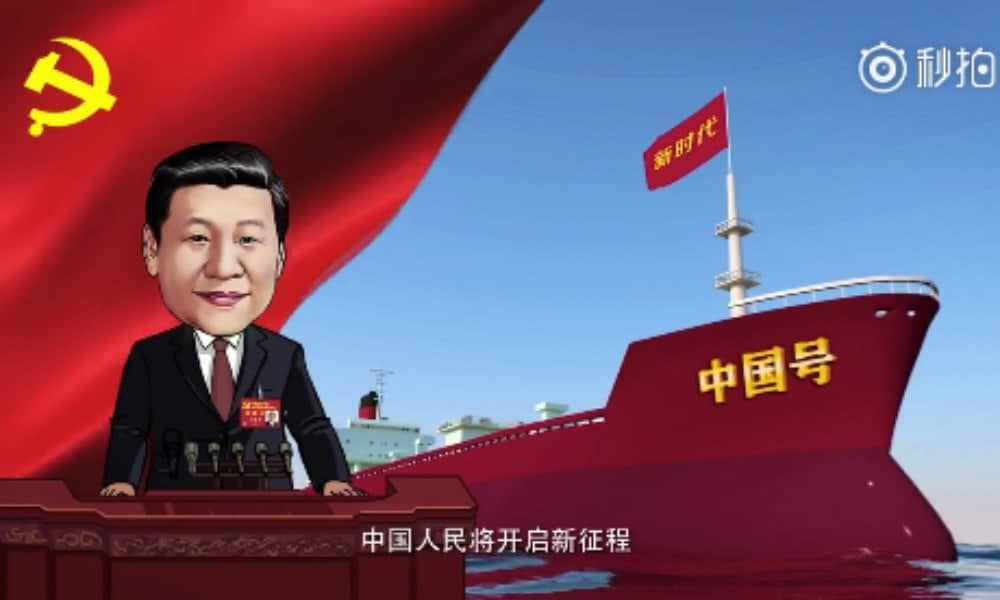

The recent APEC cartoon that made its rounds on Weibo this week summarizes Xi Jinping’s speech in a 3,5 minute animation. It first shows a group of cranes, flying from China to the coastline of Vietnam’s Da Nang where Xi is holding his keynote speech.

As Xi talks about the development of China and the start of the PRC’s “New Era,” this concept is visualized through a boat that is going forward under the leadership of Xi Jinping (see featured image).

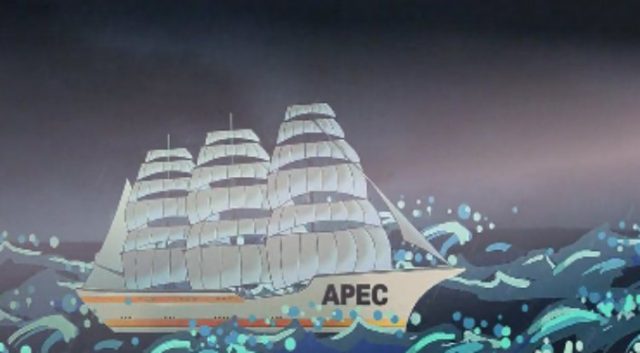

The short animation video then shows another vessel by the name of “APEC” that is in rough weather, passing icebergs of “terrorism,” “natural disasters,” or “food safety issues.” But luckily, there is a lighthouse standing up to the huge waves – and it is marked by the flag of China.

APEC: Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation.

China is a stable lighthouse amidst the wild waves.

While the audio from Xi’s speech continues throughout the animation, talking about stability in the region, the cartoon presents the APEC group of leaders and Xi meeting with various leaders, leading to the final part that shows a world connected through boats, trains, airplanes, and the internet.

The very last fragment of the animation shows a fleet of boats going forward, “together building a better tomorrow for the Asia-Pacific,” with the leading boat carrying the Chinese flag.

The animation was shared on video platform Miaopai and Weibo by state media such as CCTV (@央视网), Global Times (@环球网), China Economy (@中国经济网), and others.

Xi Jinping the Cartoon

It is not the first time that the cartoon image of President Xi is propagated online by Chinese state media. Over the past years, various key political concepts, events, and ideological messages have been spread online through animations, with a central role for Xi Jinping.

This trend became particularly apparent earlier this year during the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative and during the 19th National Party Congress; both crucial moment for Beijing’s top leadership in 2017.

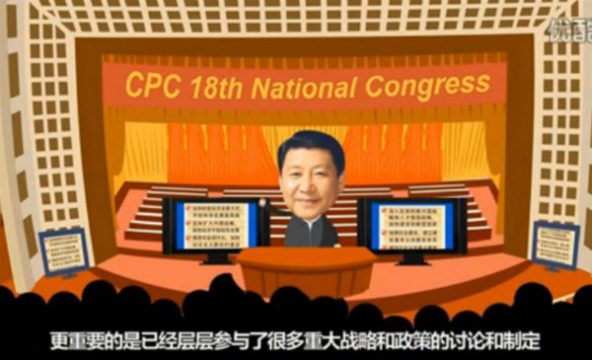

Xi Jinping was first launched as a cartoon image in 2013, when a video titled ‘How a Political Leader was Tempered’ (领导人是怎样炼成的) went viral online. At the time , Chinese state media reported that the identity of the video’s author “remained unknown.”

Xi first appeared as a cartoon in 2013.

But not long after this success, the first official release of a Xi Jinping cartoon followed. The series ‘Where did Xi’s Time Go?’ (习主席的时间都去哪了) was designed by media outlet Qianlong.com, and was propagated on major websites as well as new apps.

“More attractive than text news, the comic graphic news could reach readers’ heart and it suits modern reading habits,” the chief editor of Qianlong proudly said about the Xi cartoon.

‘Where did Xi’s time go?’ was issued in 2013.

In 2014, another cartoon series of Xi Jinping was released by Chinese state media. According to People’s Daily, the image of cartoon Xi, drawn by cartoonist Jiao Haiyang (焦海洋), made it possible for the media to depict the country’s leader in a “fun and vivid way”, showing the President as “modest,” “approachable,” and “in touch with the people.”

Xi Jinping by Jiao Haiyang for People’s Daily in 2014.

Xi eats baozi with the people. By Jiao Haiyang.

Xi Jinping meets a sanitation worker. By Jiao Haiyang.

In 2015, Xi made another return as a cartoon hero fighting corruption. The cartoon, uploaded to Youku by the mysterious ‘Chaoyang Studios,’ was widely shared by state media outlets such as People’s Daily (Gan 2015).

The exposure of Xi as a cartoon image increased thereafter in 2016 and 2017, with China Daily even launching a ‘cartoon commentary’ section. The ‘cartoon commentary’ section posts short animations of Xi Jinping during and after important political events, such as Xi’s Europe-Asia tour in June 2016, the Central Asia tour in June of 2017 or the Hong Kong visit in July.

‘Cartoon commentary’ from China Daily 2016: Xi’s Europe-Asia Tour.

China Daily ‘cartoon commentary’ during Xi’s visit to Hong Kong in July 2017.

Most of the animated Xi cartoons that are widely shared on Chinese social media over the recent two years, including the official media ‘cartoon commentaries’, have been credited to a cartoonist named Liao Tingting (廖婷婷).

Xi Jinping by Liao Tingting.

‘Liao’s’ cartoons have a distinct style that is different from that of Jiao Haiyang or the Qianlong designers; Xi always has the same friendly face, which is relatively big for his body. The cartoons have bright colors and often have a simplicity to them which is comparable to the drawings in children’s books.

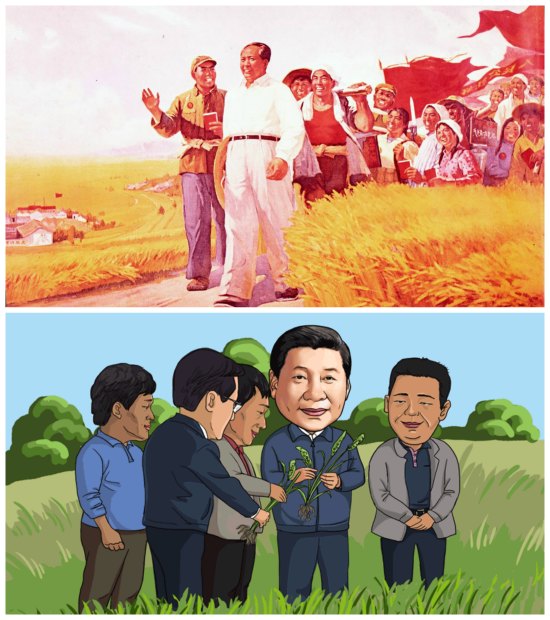

‘Propaganda Poster’ in the Social Media Age

Colorful images depicting important events or developments, often with a special focus on Mao Zedong, have played an important role in Chinese state propaganda since the founding of the PRC in 1949. The propaganda poster was an especially relevant medium within this type of state-sponsored propaganda art. With bright colors and powerful images, posters could easily grab the attention of the people, and could also transmit messages to the many illiterate Chinese (Landsberger 2001, 541; Van der Heijden&Landsberger 2008).

But in an era of fast online media and smartphone-scrolling youth, Chinese leaders are changing their propaganda tactics. As noted by Chow (2017) in The Diplomat:

“China is hoping to reinforce belief in the Communist Party, Chinese nationalism, and socialist values through social media. The ruling party fears that it is losing the battle for hearts and minds – particularly among Internet-savvy millennials who have grown up with Western movies, music, and television.”

Besides other new ways to disseminate political messages (such as rap music, mobile games), short animated cartoons or gifs are now an important vehicle for propaganda; they can communicate strong audiovisual messages in bite-sized chunks, making it easy to digest for an audience that is overwhelmed by online information and is not interested in listening to hour-long speeches.

Although the step from propaganda poster to online animation seems big, the idea remains the same: using bright colors and simple design to attract people’s attention and communicate a strong message through a medium that can be easily placed in many locations, reaching a great number of people.

Besides communicating messages about China’s development and its role in the world today, state-sponsored Xi cartoons also convey a different message. Namely that Xi Jinping is a very likable and approachable leader.

The manner in which this message is conveyed matters greatly: the control should lie with Chinese authorities. When Chinese netizens compared President Xi to Winnie the Pooh, images of the friendly bear were censored soon after they went viral.

On Weibo, the animated cartoons of Xi’s speeches and important moments already seem to have become a normal part of the everyday social media landscape. While the reactions to the first series were generally positive, with netizens calling them “so cute” (好萌), the later videos seem to have become accepted as just another way for state media to communicate news to the people.

‘Xi the cartoon’ has become part of netizens’ daily online-scrolling routines. In this regard, propaganda departments have succeeded in bringing a likable and approachable Xi “in touch with the people.”

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

References & Further Reading

Chow, Eugene. 2017. “China’s Propaganda Goes Viral.” The Diplomat, June 29 https://thediplomat.com/2017/06/chinas-propaganda-goes-viral/ [14.11.17].

Creemers, Rogier. 2017. “Cyber China: Upgrading Propaganda, Public Opinion Work and Social Management for the Twenty-First Century.” Journal of Contemporary China (26): 85-100.

Gan, Nectar. 2015. “Cartoon Xi Jinping Returns in New Animated Adventures.” South China Morning Post, February 21 http://www.scmp.com/news/china/article/1719881/cartoon-xi-jinping-returns-new-animated-adventures [14.11.17].

Landsberger, Stefan R. 2001. “Learning by What Example? Educational Propaganda in Twenty-first Century China.” Critical Asian Studies 33(4): 541-571.

Van der Heijden, Marien & Stefan Landsberger. 2008. Chinese Propaganda Posters. Amsterdam: International Institute of Social History. Available online at http://www.iisg.nl/publications/chineseposters.pdf [14.11.17].

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2017 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

You may like

China Arts & Entertainment

How K-pop Fans and the 13-Year-Old Daughter of Baidu VP Sparked a Debate on Online Privacy

What began as K-pop fan outrage targeting a snarky commenter quickly escalated into a Baidu-linked scandal and a broader conversation about data privacy on Chinese social media.

Published

3 days agoon

March 26, 2025By

Ruixin Zhang

For an ordinary person with just a few followers, a Weibo account can sometimes be like a refuge from real life—almost like a private space on a public platform—where, along with millions of others, they can express dissatisfaction about daily annoyances or vent frustration about personal life situations.

But over recent years, even the most ordinary social media users could become victims of “opening the box” (开盒 kāihé)—the Chinese internet term for doxxing, meaning the deliberate leaking of personal information to expose or harass someone online.

A K-pop Fan-Led Online Witch Hunt

On March 12, a Chinese social media account focusing on K-pop content, Yuanqi Taopu Xuanshou (@元气桃浦选手), posted about Jang Wonyoung, a popular member of the Korean girl group IVE. As the South Korean singer and model attended Paris Fashion Week and then flew back the same day, the account suggested she was on a “crazy schedule.”

In the comment section, one female Weibo user nicknamed “Charihe” replied:

💬 “It’s a 12-hour flight and it’s not like she’s flying the plane herself. Isn’t sleeping in business class considered resting? Who says she can’t rest? What are you actually talking about by calling this a ‘crazy schedule’..”

Although the comment may have come across as a bit snarky, it was generally lighthearted and harmless. Yet unexpectedly, it brought disaster upon her.

That very evening, the woman nicknamed Charihe was bombarded with direct messages filled with insults from fans of Jang Wonyoung and IVE.

Ironically, Charihe’s profile showed she was anything but a hater of the pop star—her Weibo page included multiple posts praising Wonyoung’s beauty and charm. But that context was ignored by overzealous fans, who combed through her social media accounts looking for other posts to criticize, framing her as a terrible person.

After discovering through Charihe’s account that she was pregnant, Jang Wonyoung’s fans escalated their attacks by targeting her unborn child with insults.

The harassment did not stop there. Around midnight, fans doxxed Charihe, exposing her personal information, workplace, and the contact details of her family and friends. Her friends were flooded with messages, and some were even targeted at their workplaces.

Then, they tracked down Charihe’s husband’s WeChat account, sent him screenshots of her posts, and encouraged him to “physically punish” her.

The extremity of the online harassment finally drew backlash from netizens, who expressed concern for this ordinary pregnant woman’s situation:

💬 “Her entire life was exposed to people she never wanted to know about.”

💬 “Suffering this kind of attack during pregnancy is truly an undeserved disaster.”

Despite condemnation of the hate, some extreme self-proclaimed “fans” remained relentless in the online witch hunt against Charihe.

Baidu Takes a Hit After VP’s 13-Year-Old Daughter Is Exposed

One female fan, nicknamed “YourEyes” (@你的眼眸是世界上最小的湖泊), soon started doxxing commenters who had defended her. The speed and efficiency of these attacks left many stunned at just how easy it apparently is to trace social media users and doxx them.

Digging into old Weibo posts from the “YourEyes” account, people found she had repeatedly doxxed people on social media since last year, using various alt accounts.

She had previously also shared information claiming to study in Canada and boasted about her father’s monthly salary of 220,000 RMB (approx. $30.3K), along with a photo of a confirmation document.

Piecing together the clues, online sleuths finally identified her as the daughter of Xie Guangjun (谢广军), Vice President of Baidu.

From an online hate campaign against an innocent, snarky commenter, the case then became a headline in Chinese state media, and even made international headlines, after it was confirmed that the user “YourEyes”—who had been so quick to dig up others’ personal details—was in fact the 13-year-old daughter of Xie Guangjun, vice president at one of China’s biggest tech giants.

On March 17, Xie Guangjun posted the following apology to his WeChat Moments:

💬 “Recently, my 13-year-old daughter got into an online dispute. Losing control of her emotions, she published other people’s private information from overseas social platforms onto her own account. This led to her own personal information also getting exposed, triggering widespread negative discussion.

As her father, I failed to detect the problem in time and failed to guide her in how to properly handle the situation. I did not teach her the importance of respecting and protecting the privacy of others and of herself, for which I feel deep regret.

In response to this incident, I have communicated with my daughter and sternly criticized her actions. I hereby sincerely apologize to all friends affected.

As a minor, my daughter’s emotional and cognitive maturity is still developing. In a moment of impulsiveness, she made a wrong decision that hurt others and, at the same time, found herself caught in a storm of controversy that has subjected her to pressure and distress far beyond her age.

Here, I respectfully ask everyone to stop spreading related content and to give her the opportunity to correct her mistakes and grow.

Once again, I extend my apologies, and I sincerely thank everyone for your understanding and kindness.”

The public response to Xie’s apology has been largely negative. Many criticized the fact that it was posted privately on WeChat Moments rather than shared on a public platform like Weibo. Some dismissed the statement as an attempt to pacify Baidu shareholders and colleagues rather than take real accountability.

Netizens also pointed out that the apology avoided addressing the core issue of doxxing. Concerns were raised about whether Xie’s position at Baidu—and potential access to sensitive information—may have helped his daughter acquire the data she used to doxx others.

Adding fuel to the speculation were past conversations allegedly involving one of @YourEyes’ alt accounts. In one exchange, when asked “Who are you doxxing next?” she replied, “My parents provided the info,” with a friend adding, “The Baidu database can doxx your entire family.”

Following an internal investigation, Baidu’s head of security, Chen Yang (陈洋), stated on the company’s internal forum that Xie Guangjun’s daughter did not obtain data from Baidu but from “overseas sources.”

However, this clarification did little to reassure the public—and Baidu’s reputation has taken a hit. The company has faced prior scandals, most notably a the 2016 controversy over profiting from misleading medical advertisements.

Online Vulnerability

Beyond Baidu’s involvement, the incident reignited wider concerns about online privacy in China. “Even if it didn’t come from Baidu,” one user wrote, “the fact that a 13-year-old can access such personal information about strangers is terrifying.”

Using the hashtag “Reporter buys own confidential data” (#记者买到了自己的秘密#), Chinese media outlet Southern Metropolis Daily (@南方都市报) recently reported that China’s gray market for personal data has grown significantly. For just 300 RMB ($41), their journalist was able to purchase their own household registration data.

Further investigation uncovered underground networks that claim to cooperate with police, offering a “70-30 profit split” on data transactions.

These illegal data practices are not just connected to doxxing but also to widespread online fraud.

In response, some netizens have begun sharing guides on how to protect oneself from doxxing. For example, they recommend people disable phone number search on apps like WeChat and Alipay, hide their real name in settings, and avoid adding strangers, especially if they are active in fan communities.

Amid the chaos, K-pop fan wars continue to rage online. But some voices—such as influencer Jingzai (@一个特别虚荣的人)—have pointed out that the real issue isn’t fandom, but the deeper problem of data security.

💬 “You should question Baidu, question the telecom giants, question the government, and only then, fight over which fan group started this.”

As for ‘Charihe,’ whose comment sparked it all—her account is now gone. Her username has become a hashtag. For some, it’s still a target for online abuse. For others, it is a reminder of just how vulnerable every user is in a world where digital privacy is far from guaranteed.

By Ruixin Zhang

Independently covering digital China for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Digital

Chinese Netizens Turn to Tim Cook Over Battery Factory’s Illegal Overtime

Is turning to Western suppliers an effective way for workers to pressure domestic companies into complying with labor laws?

Published

1 week agoon

March 20, 2025

We include this content in the Weibo Watch newsletter. Subscribe to get it in your inbox 📩

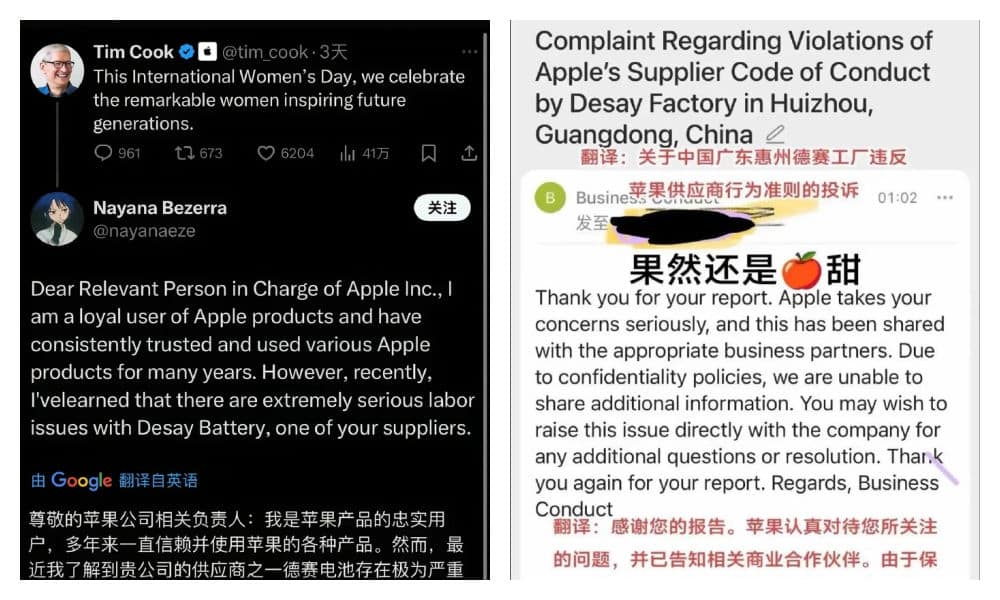

Recently, Chinese netizens have started reaching out to Apple and its CEO Tim Cook in order to put pressure on a state-owned battery factory accused of violating labor laws.

The controversy involves the Huizhou factory of Desay Battery (德赛电池), known for producing lithium batteries for the high-end smartphone market, including Apple and Samsung. The factory caught netizens’ attention after a worker exposed in a video that his superiors were deducting three days of wages because he worked an 8-hour shift instead of the company’s “mandatory 10-hour on-duty.” Compulsory overtime violates China’s labor laws.

In response, the worker and other netizens started to let Apple know about the situation through email and social media, trying to put pressure on the factory by highlighting its position in the Apple supply chain. In at least one instance, Apple confirmed receipt of the complaint. (Meanwhile, on Tim Cook’s official Weibo account, the comment section underneath his most recent post is clearly being censored.)

Screenshot of replies on X underneath a post by Tim Cook on International Women’s Day.

The factory, however, has denied the allegations, , claiming that the video creator was spreading untruths and that they had reported him to authorities. His content has since also been removed. A staff member at Desay Battery maintained that they adhere to the 8-hour workday and appropriately compensate workers for overtime.

At the same time, Desay Battery issued an official statement, admitting to “management oversights regarding employee rights protection” (“保障员工权益的管理上存在疏漏”) and promising to do better in safeguarding employee rights.

One NetEase account (大风文字) suggested that for Chinese workers to effectively expose labor violations, reporting them to Western suppliers or EU regulators is an effective way to force domestic companies to respect labor laws.

Another commentary channel (上峰视点) was less optimistic about the effectiveness, arguing that companies like Apple would be quick to drop suppliers over product quality issues but more willing to turn a blind eye to labor violations—since cheap labor remains a key competitive advantage in Chinese manufacturing.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

How K-pop Fans and the 13-Year-Old Daughter of Baidu VP Sparked a Debate on Online Privacy

Squat or Sit? China’s Great Toilet Debate and the Problem of Footprints on the Seat

Weibo Watch: The Great Squat vs Sitting Toilet Debate in China🧻

Chinese Netizens Turn to Tim Cook Over Battery Factory’s Illegal Overtime

Revisiting China’s Most Viral Resignation Letter: “The World Is So Big, I Want to Go and See It”

Our Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Beyond the Box Office: What’s Behind Ne Zha 2’s Success?

Weibo Watch: Christmas in China Is Everywhere and Nowhere

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

15 Years of Weibo: The Evolution of China’s Social Media Giant

Tuning Into the Year of the Snake

The ‘China-chic Girl’ Image and the Realities of China’s Competitive Food Delivery Market

TikTok Refugees, Xiaohongshu, and the Letters from Li Hua

“Black Myth: Wukong”: From Gaming Screens to the CMG Spring Festival Gala?

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight11 months ago

China Insight11 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music12 months ago

China Music12 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

-

China Arts & Entertainment11 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment11 months agoSinging Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments