What's on Weibo

Hidden Hotel Cameras in Shijiazhuang: Controversy and Growing Distrust

After a Chinese blogger exposed the alarming presence of hidden cameras in hotels, public outrage and mistrust soared about privacy violations and the lack of accountability from local authorities.

Published

6 months agoon

By

Ruixin Zhang

Could it be that someone is watching you while you think you’re all alone in your private hotel room? Without realizing it, some guesthouses or hotels may have hidden cameras secretly recording their guests. This issue has long been a source of concern in China and has recently become a hot topic again.

The Chinese Douyin and Weibo blogger @ShadowsDontLie (@影子不会说谎), an ‘anti-fraud’ influencer, has made it his mission to expose hidden cameras in guesthouses. Over time, he has created several videos with his team, often following tips from his followers, where he searches for these secret cameras—sometimes concealed in the most unexpected places.

Pinhole camera found in plant decoration in hotel room, screenshot of video.

On September 23 of this year, @ShadowsDontLie posted a video in which he exposed hidden cameras in hotels and guesthouses in Shijiazhuang, the capital city of Hebei Province in northern China. In the viral video, the blogger revealed that this wasn’t his first time investigating the issue in Shijiazhuang.

As early as July, he had uncovered hidden cameras at the Huaqiang Plaza (华强广场). However, after hotel staff allegedly pressured him into signing a non-disclosure agreement and local officials became involved, he agreed not to expose the issue, on the condition that the authorities would conduct an internal investigation.

‘Shadows Don’t Lie’ pointing out one of the hidden cameras.

In September, after a tip-off from a follower that the hidden cameras had still not been removed, the blogger returned and livestreamed his search. During the video, he and his colleagues were confronted and even assaulted by individuals who appeared to be associated with the hotel and guesthouse.

The incident garnered widespread attention from netizens, who praised @ShadowsDontLie for his courage and sense of justice. Many were shocked by the boldness and arrogance of the local hotel and guesthouse staff, who, even in the presence of police captured on video, appeared unfazed by the exposure.

“Who knows how deep the corruption runs?”

After the incident went viral, the Shijiazhuang police issued a statement, claiming that the suspects responsible for installing the cameras had been detained and were not connected to the hotel owners, implying the owners’ innocence.

However, this explanation failed to convince the public. In one of the blogger’s videos, a hotel owner can clearly be heard saying, “The camera is only connected to my phone.” What raised even more suspicion was the fact that the owner casually referred to one of the arriving police officers as “Old Zhou” (老周), suggesting a close relationship. This, combined with the apparent cooperation between the police and the owner, deepened the public’s doubts.

Influencer @FrostLeaf (@霜叶) questioned the credibility of the official statements. In his comments section, growing distrust toward local law enforcement was evident. A top comment read, “These days, the official blue background with white text [used in police statements] is just a way to brush you off—what can you do about it?”

As the situation caused an online commotion, @ShadowsDontLie received numerous threats, some of his videos were taken down, and there were even accusations that he had staged the entire incident and had installed the cameras himself.

The incident not only heightened public concern over privacy protection, but it also made people doubt the integrity of the guesthouse industry in Shijiazhuang, which then also impacted other local businesses.

On the 25th, he posted again, revealing that local officials from Shijiazhuang had invited him for a face-to-face meeting. Before attending, he recorded a video disclosing his location, the people accompanying him, and affirming to the public that he would not voluntarily delete any videos—a move that suggested he was preparing for the worst.

After this post, even more netizens expressed concerns for his safety. Comments like “It’s a trap” (“鸿门宴”), “Don’t go, you might not make it back,” and “Who knows how deep the corruption runs” highlighted widespread suspicion. Many believed there was collusion between local hotel businesses and government officials, particularly regarding the hidden camera issue.

Several hours after the blogger’s video about meeting with local officials, he posted yet another update. This time, he issued a public apology on behalf of him and his team to the people of Shijiazhuang, addressing two main points: first, he apologized for any reputational or economic harm his actions may have caused local businesses, and second, for potentially “damaging” the city’s tourism image ahead of the upcoming National Day holiday. He also offered to film promotional videos for Shijiazhuang for free.

However, most commenters felt that @ShadowsDontLie had nothing to apologize for and that it was not his responsibility to protect the image of Shijiazhuang’s hospitality industry. Others believed the statement from the blogger and his team was simply the result of pressure from local authorities. One person commented, “So, silencing the person who raised the issue means there’s no issue anymore?”

“China’s version of South Korea’s infamous ‘Nth Room’ scandal”

Besides the concerns over the vigilante blogger, the issue of hidden cameras in hotels itself continues to spark outrage.

According to a report shared by China Kandian, a former guesthouse owner revealed the existence of a black market for illicit filming since at least as early as 2017. She explained that many guesthouse owners intentionally install hidden cameras during renovations and stream the footage to the cloud. Some owners reportedly earn five-figure incomes daily by selling video clips or granting access to live streams.

Others in the industry have exposed how profits from live streaming far exceed revenue from room bookings. These guesthouses often lure guests with appealing décor and low rates, only to profit from hidden camera footage. When caught, they typically claim the cameras were installed by guests.

These claims are not baseless. Blogger Li Chunji (@北国佳人李春姬) has compiled numerous reports over the years of hidden cameras being found in hotels and the sale of such footage, with cases reported across China. She even discovered livestreaming platforms outside China’s firewall that advertised “hotel peep cams” and “surveillance videos.”

Similarly, influencer @Xianzi (@弦子与她的朋友们) received a tip-off and uncovered a website featuring live streams from guesthouses and hotels in China. The site not only offered “real-time surveillance” but also “replays,” which left many people horrified. Some have compared this to China’s version of South Korea’s infamous “Nth Room” scandal, which involved criminals who blackmailed victims (including minors), into making sexually exploitative videos to sell on Telegram between 2018 and 2020.

Example of hidden camera streams.

In response to the public’s panic and anger, the government’s indifferent reaction, lenient penalties, and lack of clear accountability have only fueled further anxiety.

Online discussions have surged under hashtags like “Will You [Still] Stay In A Guesthouse During National Day?” (#国庆出游还住民宿吗#), along with tips on how to check for hidden cameras.

However, as public welfare influencer @BuGuoJun (@补果君) pointed out, “We shouldn’t have to keep teaching people how to detect hidden cameras. Instead, we should be asking how to shut down all hotels with hidden cameras.”

For many citizens, however, who are increasingly turning to grassroots justice rather than relying on official channels, this may seem like an idealistic dream.

Beneath these discussions—whether viewed as public paranoia or a reflection of reality—there remains a deep mistrust of local authorities. This is why many people place their faith in grassroots “vigilantes” like @ShadowsDontLie rather than the city police to seek justice.

In the comment sections of his posts, countless netizens expressed their gratitude for his efforts. Despite the threats and pressure he faced, one comment summed up the public’s sentiment: “We should be thanking you instead.”

By Ruixin Zhang

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Ruixin is a Leiden University graduate, specializing in China and Tibetan Studies. As a cultural researcher familiar with both sides of the 'firewall', she enjoys explaining the complexities of the Chinese internet to others.

You may like

China Arts & Entertainment

How K-pop Fans and the 13-Year-Old Daughter of Baidu VP Sparked a Debate on Online Privacy

What began as K-pop fan outrage targeting a snarky commenter quickly escalated into a Baidu-linked scandal and a broader conversation about data privacy on Chinese social media.

Published

2 days agoon

March 26, 2025By

Ruixin Zhang

For an ordinary person with just a few followers, a Weibo account can sometimes be like a refuge from real life—almost like a private space on a public platform—where, along with millions of others, they can express dissatisfaction about daily annoyances or vent frustration about personal life situations.

But over recent years, even the most ordinary social media users could become victims of “opening the box” (开盒 kāihé)—the Chinese internet term for doxxing, meaning the deliberate leaking of personal information to expose or harass someone online.

A K-pop Fan-Led Online Witch Hunt

On March 12, a Chinese social media account focusing on K-pop content, Yuanqi Taopu Xuanshou (@元气桃浦选手), posted about Jang Wonyoung, a popular member of the Korean girl group IVE. As the South Korean singer and model attended Paris Fashion Week and then flew back the same day, the account suggested she was on a “crazy schedule.”

In the comment section, one female Weibo user nicknamed “Charihe” replied:

💬 “It’s a 12-hour flight and it’s not like she’s flying the plane herself. Isn’t sleeping in business class considered resting? Who says she can’t rest? What are you actually talking about by calling this a ‘crazy schedule’..”

Although the comment may have come across as a bit snarky, it was generally lighthearted and harmless. Yet unexpectedly, it brought disaster upon her.

That very evening, the woman nicknamed Charihe was bombarded with direct messages filled with insults from fans of Jang Wonyoung and IVE.

Ironically, Charihe’s profile showed she was anything but a hater of the pop star—her Weibo page included multiple posts praising Wonyoung’s beauty and charm. But that context was ignored by overzealous fans, who combed through her social media accounts looking for other posts to criticize, framing her as a terrible person.

After discovering through Charihe’s account that she was pregnant, Jang Wonyoung’s fans escalated their attacks by targeting her unborn child with insults.

The harassment did not stop there. Around midnight, fans doxxed Charihe, exposing her personal information, workplace, and the contact details of her family and friends. Her friends were flooded with messages, and some were even targeted at their workplaces.

Then, they tracked down Charihe’s husband’s WeChat account, sent him screenshots of her posts, and encouraged him to “physically punish” her.

The extremity of the online harassment finally drew backlash from netizens, who expressed concern for this ordinary pregnant woman’s situation:

💬 “Her entire life was exposed to people she never wanted to know about.”

💬 “Suffering this kind of attack during pregnancy is truly an undeserved disaster.”

Despite condemnation of the hate, some extreme self-proclaimed “fans” remained relentless in the online witch hunt against Charihe.

Baidu Takes a Hit After VP’s 13-Year-Old Daughter Is Exposed

One female fan, nicknamed “YourEyes” (@你的眼眸是世界上最小的湖泊), soon started doxxing commenters who had defended her. The speed and efficiency of these attacks left many stunned at just how easy it apparently is to trace social media users and doxx them.

Digging into old Weibo posts from the “YourEyes” account, people found she had repeatedly doxxed people on social media since last year, using various alt accounts.

She had previously also shared information claiming to study in Canada and boasted about her father’s monthly salary of 220,000 RMB (approx. $30.3K), along with a photo of a confirmation document.

Piecing together the clues, online sleuths finally identified her as the daughter of Xie Guangjun (谢广军), Vice President of Baidu.

From an online hate campaign against an innocent, snarky commenter, the case then became a headline in Chinese state media, and even made international headlines, after it was confirmed that the user “YourEyes”—who had been so quick to dig up others’ personal details—was in fact the 13-year-old daughter of Xie Guangjun, vice president at one of China’s biggest tech giants.

On March 17, Xie Guangjun posted the following apology to his WeChat Moments:

💬 “Recently, my 13-year-old daughter got into an online dispute. Losing control of her emotions, she published other people’s private information from overseas social platforms onto her own account. This led to her own personal information also getting exposed, triggering widespread negative discussion.

As her father, I failed to detect the problem in time and failed to guide her in how to properly handle the situation. I did not teach her the importance of respecting and protecting the privacy of others and of herself, for which I feel deep regret.

In response to this incident, I have communicated with my daughter and sternly criticized her actions. I hereby sincerely apologize to all friends affected.

As a minor, my daughter’s emotional and cognitive maturity is still developing. In a moment of impulsiveness, she made a wrong decision that hurt others and, at the same time, found herself caught in a storm of controversy that has subjected her to pressure and distress far beyond her age.

Here, I respectfully ask everyone to stop spreading related content and to give her the opportunity to correct her mistakes and grow.

Once again, I extend my apologies, and I sincerely thank everyone for your understanding and kindness.”

The public response to Xie’s apology has been largely negative. Many criticized the fact that it was posted privately on WeChat Moments rather than shared on a public platform like Weibo. Some dismissed the statement as an attempt to pacify Baidu shareholders and colleagues rather than take real accountability.

Netizens also pointed out that the apology avoided addressing the core issue of doxxing. Concerns were raised about whether Xie’s position at Baidu—and potential access to sensitive information—may have helped his daughter acquire the data she used to doxx others.

Adding fuel to the speculation were past conversations allegedly involving one of @YourEyes’ alt accounts. In one exchange, when asked “Who are you doxxing next?” she replied, “My parents provided the info,” with a friend adding, “The Baidu database can doxx your entire family.”

Following an internal investigation, Baidu’s head of security, Chen Yang (陈洋), stated on the company’s internal forum that Xie Guangjun’s daughter did not obtain data from Baidu but from “overseas sources.”

However, this clarification did little to reassure the public—and Baidu’s reputation has taken a hit. The company has faced prior scandals, most notably a the 2016 controversy over profiting from misleading medical advertisements.

Online Vulnerability

Beyond Baidu’s involvement, the incident reignited wider concerns about online privacy in China. “Even if it didn’t come from Baidu,” one user wrote, “the fact that a 13-year-old can access such personal information about strangers is terrifying.”

Using the hashtag “Reporter buys own confidential data” (#记者买到了自己的秘密#), Chinese media outlet Southern Metropolis Daily (@南方都市报) recently reported that China’s gray market for personal data has grown significantly. For just 300 RMB ($41), their journalist was able to purchase their own household registration data.

Further investigation uncovered underground networks that claim to cooperate with police, offering a “70-30 profit split” on data transactions.

These illegal data practices are not just connected to doxxing but also to widespread online fraud.

In response, some netizens have begun sharing guides on how to protect oneself from doxxing. For example, they recommend people disable phone number search on apps like WeChat and Alipay, hide their real name in settings, and avoid adding strangers, especially if they are active in fan communities.

Amid the chaos, K-pop fan wars continue to rage online. But some voices—such as influencer Jingzai (@一个特别虚荣的人)—have pointed out that the real issue isn’t fandom, but the deeper problem of data security.

💬 “You should question Baidu, question the telecom giants, question the government, and only then, fight over which fan group started this.”

As for ‘Charihe,’ whose comment sparked it all—her account is now gone. Her username has become a hashtag. For some, it’s still a target for online abuse. For others, it is a reminder of just how vulnerable every user is in a world where digital privacy is far from guaranteed.

By Ruixin Zhang

Independently covering digital China for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Insight

Squat or Sit? China’s Great Toilet Debate and the Problem of Footprints on the Seat

From squatting to standing on seats: the messy reality of sitting toilets in Beijing malls.

Published

3 days agoon

March 25, 2025

FROM THE WEIBO WATCH PREMIUM NEWSLETTER

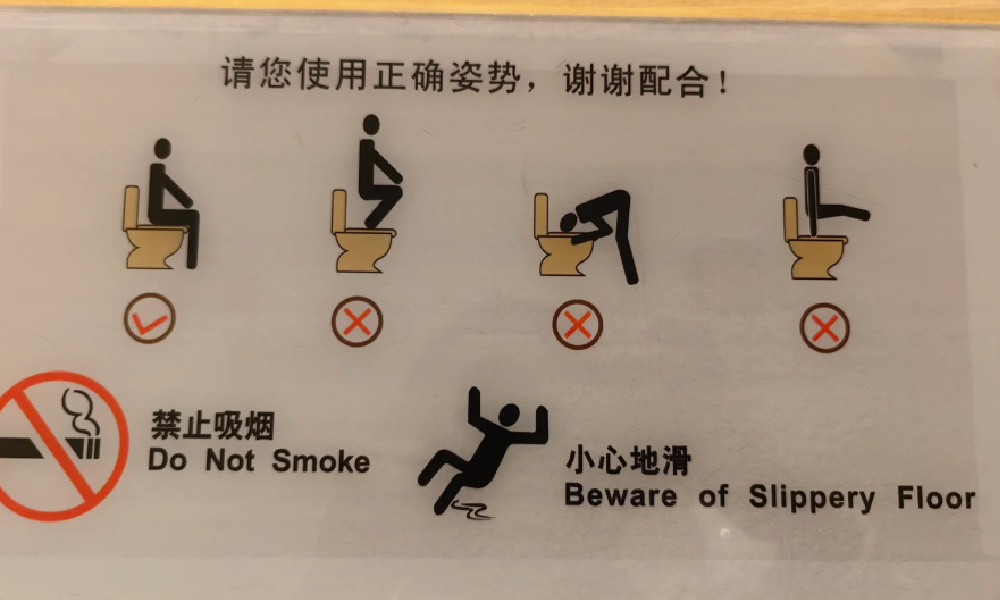

Shoe prints on top of the toilet seat are never a pretty sight. To prevent people from squatting over Western-style sitting toilets, there are some places that will place stickers above the toilet, reminding people that standing on the seat is strictly forbidden.

For years, this problem has sparked debate. Initially, these discussions would mostly take place outside of China, in places with a large number of Chinese tourists. In Switzerland, for example, the famous Rigi Railways caused controversy for introducing separate trains with special signs explaining to tourists, especially from China, how (not) to use the toilet.

Squat toilets are common across public areas in China, especially in rural regions, for a mix of historical, cultural, and practical reasons. There is also a long-held belief — backed by studies (like here or here) — that the squatting position is healthier for bowel movements (for more about the history of squat toilets in China, see Sixth Tone’s insightful article here).

Public squatting toilets in Beijing, images via Xiaohongshu.

Without access to the ground-level squat toilets they are used to — and feel more comfortable with — some people will climb on top of sitting toilets to use them in the way they’re accustomed to, seeing squatting as the more natural and hygienic method.

Not only does this make the toilet seat all messy and muddy, it is also quite a dangerous stunt to pull, can break the toilet, and lead to pee and poo going into all kinds of unintended directions. Quite shitty.

Squatting on toilets makes the seat dirty and can even break the toilet.

Along with the rapid modernization of Chinese public facilities and the country’s “Toilet Revolution” over the past decade, sitting toilets have become more common in urban areas, and thus the sitting-toilet-used-as-squat-toilet problem is increasingly becoming topic of public debate within China.

The Toilet Committee and Preference for Sitting Toilets

Is China slowly shifting to sitting toilets? Especially in modern malls in cities like Beijing, or even at airports, you see an increasing number of Western-style sitting toilets (坐厕) rather than squatting toilets (蹲厕).

This shift is due to several factors:

🚽📌 First, one major reason for the rise in sitting toilets in Chinese public places is to accommodate (foreign) tourists.

In 2015, China Daily reported that one of the most common complaints among international visitors was the poor condition of public toilets — a serious issue considering tourists are estimated to use public restrooms over 27 billion times per year.

That same year, China’s so-called “Toilet Revolution” (厕所革命) began gaining momentum. While not a centralized campaign, it marked a nationwide push to upgrade toilets across the country and improve sanitation systems to make them cleaner, safer, and more modern.

This movement was largely led by the tourism sector, with the needs of both domestic and international travelers in mind. These efforts, and the buzzword “Toilet Revolution,” especially gained attention when Xi Jinping publicly endorsed the campaign and connected it to promoting civilized tourism.

In that sense, China’s toilet revolution is also a “tourism toilet revolution” (旅游厕所革命), part of improving not just hygiene, but the national image presented to the world (Cheng et al. 2018; Li 2015).

🚽📌 Second, the growing number of sitting toilets in malls and other (semi)public spaces in Beijing relates to the idea that Western-style toilets are more sanitary.

Although various studies comparing the benefits of squatting and sitting toilets show mixed outcomes, sitting toilets — especially in shared restrooms — are generally considered more hygienic as they release fewer airborne germs after flushing and reduce the risk of infection (Ali 2022).

There are additional reasons why sitting toilets are favored in new toilet designs. According to Liang Ji (梁骥), vice-secretary of the Toilet Committee of the China Urban Environmental Sanitation Association (中国城市环境卫生协会厕所专业委员会), sitting toilets are also increasingly being introduced in public spaces due to practical concerns.

🚽📌 Squatting is not always easy, and can pose a safety risk, particularly for the elderly, pregnant women, and people with disabilities.

🚽📌 Then there are economic reasons: building squat toilets in malls (or elsewhere) requires a deeper floor design due to the sunken space needed below the fixture, which increases both construction time and cost.

🚽📌 Liang also points to an aesthetic factor: sitting toilets simply look more “high-end” and are easier to clean, which is why many consumer-oriented spaces prefer to install Western-style toilets.

So although there are plenty of reasons why sitting toilets are becoming a norm in newly built public spaces and trendy malls, they also lead to footprints on toilet seats — and all the problems that come with it.

The Catch 22 of Sitting vs Squad Toilets

This week, the issue became a trending topic on Weibo after Beijing News published an investigative report on it. The report suggested that most shopping malls in Beijing now have restrooms with sitting toilets, which should, in theory, be cleaner than the squat toilets of the past — but in reality, they’re often dirtier because people stand on them. This issue is more common in women’s restrooms, as men’s restrooms typically include urinals.

In researching the issue, a reporter visited several Beijing malls. In one women’s restroom, the reporter observed 23 people entering within five minutes. Although the restroom had only three squat toilets versus seven sitting ones, around 70% of the users opted for the squat toilets.

Upon inspection, most of the seven sitting toilets were dirty — despite being equipped with disposable seat covers — showing clear signs of urine stains and footprints. They found that sitting toilets being used as squat toilets is extremely common.

It’s a bit of a Catch-22. People generally prefer clean toilets, and there’s also a widespread preference for squat toilets. This leads to sitting toilets being used as squat toilets, which makes them dirty — reinforcing the preference for squat toilets, since the sitting toilets, though meant to be cleaner, end up dirtier.

In interviews with 20 women, nearly 80% said they either hover in a squat or directly squat on the toilet seat. One woman said, “I won’t sit unless I absolutely have to.” While some of those quoted in the article said that sitting toilets are more comfortable, especially for elderly people, they are still not preferred when the seats are not clean.

In the Beijing News article, the Toilet Committee’s Liang Ji suggested that while a balanced ratio of squat and sitting toilets is necessary, a gradual shift toward sitting toilets is likely the future for public restrooms in China.

How NOT to use the sitting toilet. Sign photographed by Xiaohongshu user @FREAK.00.com.

Liang also highlighted the importance of correct toilet use and the need to consider public habits in toilet design.

In Squatting We Trust

On Chinese social media, however, the majority of commenters support squatting toilets. One popular comment said:

💬 “Please make all public toilets squat toilets, with just one sitting toilet reserved for people with disabilities.”

Squatting toilets in a public toilet in a Beijing hutong area, image by Xiaohongshu user @00后饭桶.

The preference for squatting, however, doesn’t always come down to bowel movements or tradition. Many cite a lack of trust in how others use public toilets:

💬 “When it comes to things for public use, it’s best to reduce touching them directly. Honestly, I don’t trust other people…”

💬 “Squatting is the most hygienic. At least I don’t have to worry about touching something others touched with their skin.”

💬 “I hate it when all the toilets in the women’s restroom at the mall are sitting toilets. I’m almost mastering the art of doing the martial-arts squat (蹲马步).”

Others view the gradual shift toward sitting toilets as a result of Westernization:

💬 “Sitting toilets are a product of widespread ‘Westernization’ back in the day — the further south you go, the worse it gets.”

But some come to the defense of sitting toilets:

💬 “Are there really still people who think squat toilets are cleaner? The chances of stepping in poop with squat toilets are way higher than with sitting ones. Sitting toilet seats can be wiped with disinfectant or covered with paper. Some people only care about keeping themselves ‘clean’ without thinking about whether the next person might end up stepping in their mess.”

💬 One reply bluntly said: “I don’t use sitting toilets. If that’s all there is, I’ll just squat on top of it. Not even gonna bother wiping it.”

It’s clear this debate is far from over, and the issue of people standing on toilet seats isn’t going away anytime soon. As China’s toilet revolution continues, various Toilet Committees across the country may need to rethink their strategies — especially if they continue leaning toward installing more sitting toilets in public spaces.

As always, Taobao has a solution. For just 50 RMB (~$6.70), you can order an anti-slip sitting-to-squatting toilet aid through the popular e-commerce platform.

The Taobao solution.

For Chinese malls, offering these might be cheaper than dealing with broken toilets and the never-ending battle against footprints on toilet seats…

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

References:

Ali, Wajid, Dong-zi An, Ya-fei Yang, Bei-bei Cui, Jia-xin Ma, Hao Zhu, Ming Li, Xiao-Jun Ai, and Cheng Yan. 2022. “Comparing Bioaerosol Emission after Flushing in Squat and Bidet Toilets: Quantitative Microbial Risk Assessment for Defecation and Hand Washing Postures.” Building and Environment 221: 109284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109284.

Bhattacharya, Sudip, Vijay Kumar Chattu, and Amarjeet Singh. 2019. “Health Promotion and Prevention of Bowel Disorders Through Toilet Designs: A Myth or Reality?” Journal of Education and Health Promotion 8 (40). https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_198_18.

Cao, Jingrui 曹晶瑞, and Tian Jiexiong 田杰雄. 2025. “城市微调查|商场女卫生间,坐厕为何频频变“蹲坑”? [In Shopping Mall Women’s Restrooms, Why Do Sitting Toilets Frequently Turn into ‘Squat Toilets’?]” Beijing News, March 20. https://weibo.com/ttarticle/p/show?id=2309405146044773302810. Accessed March 19, 2025.

Cheng, Shikun, Zifu Li, Sayed Mohammad Nazim Uddin, Heinz-Peter Mang, Xiaoqin Zhou, Jian Zhang, Lei Zheng, and Lingling Zhang. 2018. “Toilet Revolution in China.” Journal of Environmental Management 216: 347–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.09.043.

Dai, Wangyun. 2018. “Seats, Squats, and Leaves: A Brief History of Chinese Toilets.” Sixth Tone, January 13. https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1001550. Accessed March 22, 2025.

Li, Jinzao. 2015. “Toilet Revolution for Tourism Evolution.” China Daily, April 7. https://europe.chinadaily.com.cn/opinion/2015-04/07/content_20012249_2.htm. Accessed March 22, 2025.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

How K-pop Fans and the 13-Year-Old Daughter of Baidu VP Sparked a Debate on Online Privacy

Squat or Sit? China’s Great Toilet Debate and the Problem of Footprints on the Seat

Weibo Watch: The Great Squat vs Sitting Toilet Debate in China🧻

Chinese Netizens Turn to Tim Cook Over Battery Factory’s Illegal Overtime

Revisiting China’s Most Viral Resignation Letter: “The World Is So Big, I Want to Go and See It”

Our Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Beyond the Box Office: What’s Behind Ne Zha 2’s Success?

Weibo Watch: Christmas in China Is Everywhere and Nowhere

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

15 Years of Weibo: The Evolution of China’s Social Media Giant

Tuning Into the Year of the Snake

The ‘China-chic Girl’ Image and the Realities of China’s Competitive Food Delivery Market

TikTok Refugees, Xiaohongshu, and the Letters from Li Hua

“Black Myth: Wukong”: From Gaming Screens to the CMG Spring Festival Gala?

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight11 months ago

China Insight11 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music12 months ago

China Music12 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

-

China Arts & Entertainment11 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment11 months agoSinging Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments