China Digital

In China’s “Kua Kua” Chat Groups, People Pay to Be Praised [Updated]

Money can’t buy you love, but in these ‘kua kua’ groups, they can buy you praise.

Published

6 years agoon

First published

Social media is often called a battlefield, but in these Chinese WeChat ‘Kua kua’ groups (夸夸群), people will praise you no matter what you do or say.

A new phenomenon has become a hot topic on Chinese social media these days. ‘Kua kua’ groups (夸夸群) are chat groups where people share some things about themselves – even if they are negative things – and where other people will always tell them how great they are, no matter what.

Kua kua groups (夸 ‘kuā‘ literally means ‘praise’) have become all the rage in China. People seem to love them for the mere fact that it makes them feel good about themselves.

The format is clear. Person A tells about something that is on their minds, and asks people for positive feedback. Person B, C, and D will then come forward and tell them how good or pretty they are, sometimes based on their profile photo.

One could say: “Hi everyone, I’ve just turned down a job offer, but now my future is full of uncertainty, please compliment me.” Then people in the chat group will respond and say things such as: “You look like the type of person who knows exactly what they want.”

The Kua kua praise group phenomenon allegedly began within the online community of Xi’an Jiaotong University – although some claim it was Shanghai’s Fudan University – when one person asked others in a chat group to compliment them. The idea started to compliment and praise others, and so a trend was born; first, in university (BBS) chat groups, and now on WeChat and beyond the realm of universities.

The phenomenon has been around for at least six years, but only recently started gaining widespread attention on Chinese social media. According to China’s Toutiao News, virtually every college now has its own ‘praise group.’

But the praise does not always come for free. Although many (college-based) chat groups are free to join, people who want to be complimented and are not yet a member of an existing group can join Kua kua groups when they pay for it. On Chinese e-commerce platform Taobao, there are various online shops that sell a ‘Praise group’ membership starting from 50 yuan ($7,5) per person, going up to 188 yuan ($28).

The time of praise is limited to five minutes unless you pay more. The quality of the compliments you’ll be getting also depends on how much you pay. Some groups allegedly consist of “students of great talent,” and the number of people complimenting one person could reach up to 500 people.

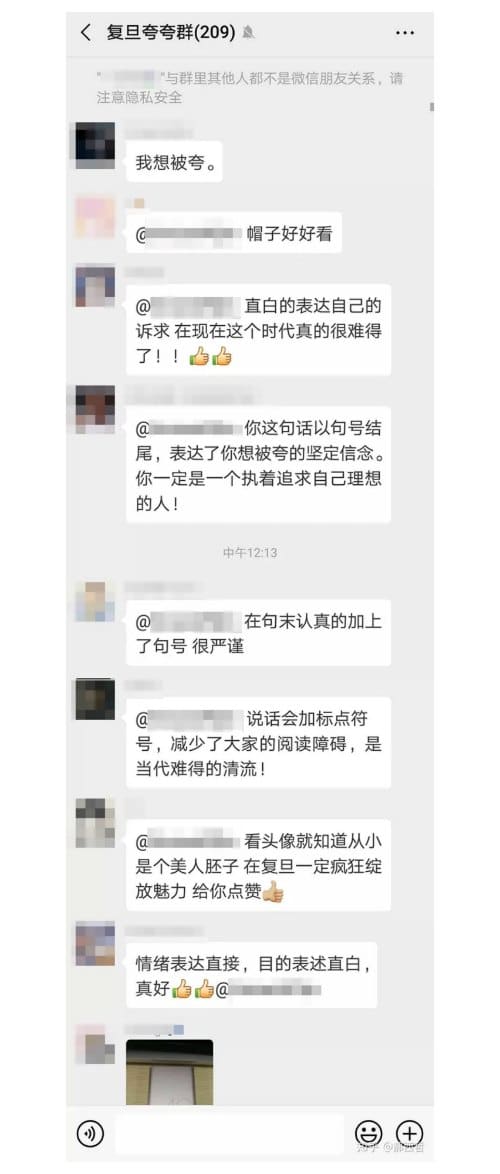

The contents of the praise could literally be anything. A simple “I want to be praised” comment could get a variety of reactions from “your hat looks nice” to “the fact that you’re so honest and straightforward about what you want is something that is hard to come across in this day and age,” to “you used a period mark [at the end of your sentence], you must be someone who is very persistent in reaching your goals.”

The fact that the “Kua kua” phenomenon is such a success in China might relate to its culture, where humility and modesty are considered ideal in day-to-day communications. When given a compliment, it is common in China to deny it or to suggest that the person giving the compliment is much better than they are (also see Cheng 2003, 30).

These chat groups, however, break away from the dominant cultural interactions: people don’t have to be polite in responding to the compliments and can wallow in the praise they paid for.

Although not as big as the “Kua Kua” group phenomenon, these kinds of groups also exist in the English-language social media sphere. On Reddit’s “Toast Me” page, for example, there are some 92,000 subscribers participating in asking and giving positive feedback to others, albeit unpaid.

The people giving compliments in the Chinese Kua kua groups are random people, some students, some staff of Taobao stores, who get hongbao, red envelopes with digital money gifts, for contributing to the group. According to some reports, some ‘customers’ end up staying the group and become a part of the team themselves.

We will follow up on this later: we booked a ‘five-minute praise session’ ourselves, but are still awaiting admission to the group…

Update: Our Kua Kua Experience

So what is the Kua kua experience like? We decided to try out for ourselves and purchased a 5-minute praise session through Taobao for 50 yuan ($7,5) from a seller that had a good rating.

After the purchase is completed, the seller will contact you with details asking for your WeChat ID. After adding, they will ask you what your ‘problem’ or issue is, and you will be put in a virtual queue until your turn comes up to be praised.

You’ll then be added to a WeChat group that has your name in the headline (ours was something like “Manya you can do it”) and that has around 200 participants.

The message posted by us was:

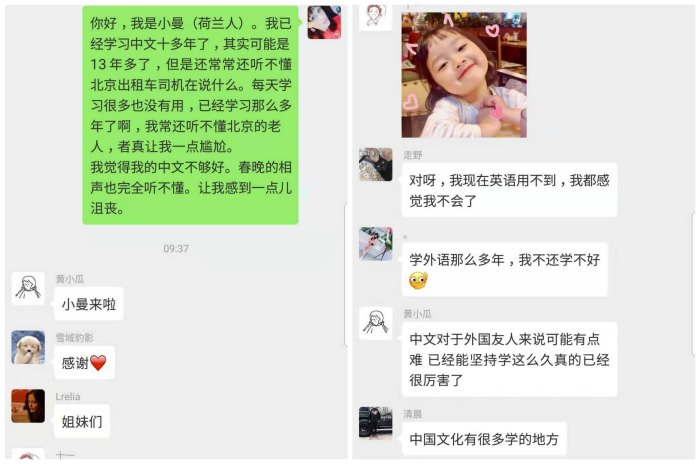

“Hello, I’m Manya (Dutch). I’ve been studying Chinese for more than ten years. In fact, I’m afraid to say it may even be more than 13 years, but I still often don’t understand what Beijing taxi drivers are saying. Even studying every day won’t help. I’ve been learning for so many years, yet I often still don’t understand what the old people in Beijing are saying. It’s a bit embarrassing. I think my Chinese is still not good enough. I can’t understand the ‘crosstalk’ [comedy sketches] during the Spring Festival Gala at all. It makes me feel a little dispirited.”

Within a matter of seconds, the screen then just fills up with positive feedback and emoji. There are dozens of comments, and they almost go too fast to read them all.

Some of the responses:

“You’re great, and even I don’t understand Beijing taxi drivers.”

“Stay confident in yourself!”

“You’re so cool.”

“You can type so many Chinese characters, who’d say your Chinese is not good enough?!”

“Manya, you’re so fantastic.”

“None of us understand what old people in Beijing are saying.”

“Chinese is just not easy to study, the fact that you’ve been doing it for so long already shows how great you are.”

“It’s incredible that you’ve already come this far.”

“A woman who is so motivated about studying really moves me, you’re my role model, you make me want to study more English.”

During the praise session, the group leader will occasionally post a hongbao [envelope with money] for the participants to receive in return for their compliments.

After five minutes, the session ends, and the people will send out some last words of encouragement. The group leader will personally thank you for being part of the group, and later, you’ll be removed from the group as the people will move on to the next person who is waiting in line to be praised.

How does it feel to be praised by some 200 people, receiving hundreds of compliments? It’s overwhelming, and even though you know it’s all just an online mechanism, and that it doesn’t matter who you are or what you say, it still makes you glow a little bit inside.

Although some experts quoted by Chinese state media warn people not to rely on these praise groups too much, there does not seem to be much harm in allowing yourself to be complimented for some minutes from time to time.

Other people reviewing the same Kua kua group apparently feel the same: “I’m super satisfied, the result is amazing.”

By Manya Koetse and Miranda Barnes

Featured image via hexun.com.

References

Cheng, Winnie. 2003. Intercultural Communication. Amsterdam, John Benjamins Publishing.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please email us.

©2019 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Stories that are authored by the What's on Weibo Team are the stories that multiple authors contributed to. Please check the names at the end of the articles to see who the authors are.

China Books & Literature

The Price of Writing Smut: Inside China’s Crackdown on Erotic Fiction

The crackdown on Haitang Literature City has led to greater awareness of it, with Chinese netizens now paying closer attention to the repression of erotic content and the struggles faced by its authors.

Published

3 weeks agoon

November 3, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

A recent crackdown on Chinese authors writing erotic webnovels has sparked increased online conversations about the Haitang Literature ‘Flower Market’ subculture, the challenges faced by prominent online smut writers, and the evolving regulations surrounding digital erotica in China. But how serious is the “crime” of writing explicit fiction China today?

You might have heard of haitang (海棠), the Chinese crabapple flower, but chances are you haven’t come across Haitang Literature City (海棠文学城)—and you’re not alone. Most people in China haven’t heard of it either. Haitang Literature City is a Taiwan-based, Chinese-language website dedicated primarily to female-oriented smut fiction, with numerous contributors from mainland China.

‘Smut fiction’ is a genre focused on explicit, sexual content and themes. Stories in this genre often emphasize the physical relationships between characters, with detailed erotic scenes. On Haitang Literature City, the most popular category is BL (Boys’ Love), which centers on romantic and erotic relationships between male characters and is written mainly for a female audience (read more here). The site also features a variety of heterosexual and lesbian stories, ranging from straightforwardly explicit to more unusual narratives. One consistent aspect across the site: most of the authors are women, writing primarily for a female readership.

Example covers of online erotica

Haitang Literature City, known as the ‘Flower Market’ (花市) by its users, has stayed relatively underground within certain reading circles. Recently, however, a help post on Weibo has brought this hidden flower market into the spotlight, sparking considerable buzz online.

The post came from a user named “Rain Painted on a Sunny Day” (@晴天画的雨), the younger sister of the Haitang author known as “Yunjian” (云间, “Between the Clouds”). On October 16, she revealed that Yunjian had been detained since June 20 and is only allowed visits from her lawyer. The arrest notice she shared cites the charge: “suspected of producing and disseminating pornographic materials for profit” (“传播淫秽物品牟利罪”).

Yunjian, a prominent author on Haitang, has been writing for over a decade, producing tens of millions of words. Her detention not only forces her to forfeit all the royalties earned over the past ten years—now labeled “illicit earnings”—but also means she faces time in prison. While “Rain Painted on a Sunny Day” acknowledged her sister’s “offense” in the post, she explained that the resulting heavy fines have left their family deeply in debt, struggling to make ends meet. After the post went up, many of Yunjian’s readers expressed heartbreak over her situation and began donating to help.

Meanwhile, Haitang Literature City, once part of an underground culture, has been brought into the spotlight. “What is Haitang Literature City? Why are the authors on this site charged with the crime of producing and distributing obscene materials? Can someone explain? It feels like a completely different world—I truly have no idea about any of this,” one Weibo user wrote. Ironically, the crackdown on the site has led to greater awareness of it, with Chinese netizens now paying closer attention to the long-standing repression of erotic content authors and the ongoing struggles they face.

MONTHS OF CRACKDOWN

“They’re back to where they started, with nothing to their name”

The crackdown on authors of explicit content from Haitang Literature City began earlier in 2024. Blogger @LXC (@洛曐曟LXC), who has been documenting these events, described how police in Anhui Province launched a cross-provincial operation in June. On June 20, they arrested Haitang distributors along with several of its most successful authors. The Haitang site quickly shut down the next day, citing maintenance. The platform remained offline for several days.

During this shutdown, many authors aware of the arrests requested that their published work be hidden. As a result, Haitang locked down all site content, allowing authors to unblock their works only upon request.

Most of the first batch of arrested authors were released around June 20, with some warning others against writing on Haitang due to the high risks involved. However, this information circulated only within a small group, so few were aware of it. Authors who had earned larger sums from their writing were unable to arrange their release and remained in custody.

How did Haitang respond? Despite being aware of the arrests, the site apparently chose not to inform other authors of the risks, possibly prioritizing profits and readership. Blogger @LXC expressed her frustration with Haitang for misleading authors who were completely unaware of the situation, as well as others who had heard unverified rumors, into unlocking their columns for subscriptions. Seeing this, several smaller authors followed suit and unlocked their works as well.

From late July to early August, another group of authors was summoned by the police. Nearly all of this second batch of arrested authors were among those who had reapplied to unblock their columns after the site had reopened. LXC suggested that the site’s mismanagement and silence about the initial arrests were responsible for these authors getting into trouble.

Yunjian remains one of the authors detained since the initial crackdown in June and has yet to be released. Alongside her, many lesser-known authors are also struggling, with many relying on their writing on Haitang to make ends meet. Among them are stay-at-home moms, low-income students, and young women from rural areas who cannot find work. After all this upheaval, their situations have only worsened, and they are likely in even more dire straits than the more well-known authors.

“To me, it’s straightforward,” @LXC wrote: “These women earned money and, as a result, improved their previously poor lives. Now that money is being taken away from them, they’re back to where they started, with nothing to their name.”

A DECADE-LONG SURVIVAL GAME

“Censorship has reached absurd levels”

This isn’t the first time Chinese online smut writers have been targeted under the country’s strict censorship laws governing pornographic content. Since China launched its “Clean Internet Campaign” in 2014, many smut writers and online fiction platforms have faced consequences. In June 2015, author Ding Yi (丁一) received a suspended three-and-a-half-year sentence for her “explicit” novels on the platform Jinjiang Literature City (晋江文学城). Another writer, Mo Xiang Tong Xiu (墨香铜臭), known for her novel The Untamed and its TV adaptation, was sentenced to three years on “illegal publishing” charges. Although her case didn’t specifically involve “producing and disseminating pornographic materials for profit,” her arrest was still part of the broader anti-pornography campaign due to the erotic themes in her work.

Another well-known BL writer, Tian Yi (天一), faced an even harsher punishment. In 2018, she was sentenced to ten and a half years in prison for her novel Absolute Domination, which included erotic depictions of gay relationships and had earned her around 150,000 yuan ($21,000) from print sales. A young woman who assisted with typesetting was also implicated—she received a four-year sentence and a 10,000-yuan ($1,400) fine for her 3,100-yuan ($430) part-time payment.

While authors have faced relentless crackdowns, websites themselves have also struggled to survive. Jinjiang Literature City (晋江文学城)—a major online fiction platform known for hosting works with mature content—has been shut down and pressured into strict content checks, with some smaller sites shut down entirely. After multiple shutdowns and rounds of scrutiny, Jinjiang became almost hyper-vigilant, enforcing its self-censorship to an extreme. Now, any sensitive terms are automatically replaced with “口口,” as the site pushes to remove anything that might be seen as explicit by the authorities.

Many netizens have pointed out that the “content review guidelines” (link) of the Jinjiang platform are ironically hilarious: “Any depiction below the neck involving intimacy, body parts, sexual acts, sexual thoughts or fantasies, sexual organs, or excessive violence is considered explicit and thus prohibited,” it states. “Even if it’s less direct and more subtle, if the scenes are too lengthy or portray the entire process, they are also counted as explicit content.” Netizens joke that as long as the reviewers think you’re being suggestive, it’s a off limits—censorship has reached absurd levels.

However, readers’ demand for pornographic works hasn’t diminished at all in this decade-long, intense survival game. A quick search for names like “Tian Yi,” “Yunjian,” or “Mr. Shenhai” on Weibo still reveals hundreds, if not thousands, of people actively seeking and sharing resources for their novels.

THE PRICE OF EROTIC CONTENT IN CHINA

“There are people who commit crimes that truly harm others who don’t face such severe sentences”

How serious is the “crime” of writing online smut in China? While Yunjian has yet to be tried or sentenced, online discussions suggest she may face severe punishment. Her royalties over the past decade exceed 250,000 yuan ($35,000), potentially classifying her case as a particularly serious offense under Chinese law for “producing and disseminating pornographic materials for profit,” due to its perceived negative impact on youth and potential to corrupt social morals. This could result in fines of one to five times her earnings and likely a prison sentence of over ten years.

Recent cases indicate similar outcomes: on October 17, a Weibo account called @HuaiBeiLiXinWrongfulCase (@淮北李鑫冤案) posted a plea, revealing that author Li Xin (李鑫), who co-wrote the historical fantasy Six Dynasties with Luo Sen (罗森), was detained on the same charge after earning 300,000 yuan ($42,118) in royalties, which led to a ten-year prison sentence. As a similarly prominent author, Yunjian may face even harsher penalties and potentially an even longer prison term.

🌟 Attention!

For 11 years, What’s on Weibo has remained a 100% independent blog, fueled by our passion to write about China’s digital culture and online trends. Over a year ago, we introduced a soft paywall to ensure the sustainability of this platform. We’re grateful to all readers who’ve subscribed since 2022. Your support has been invaluable. But we need more subscribers to continue our work. If you appreciate our content and want to support independent coverage on digital China, please become a subscriber today. Your support keeps What’s on Weibo going strong!

Can writing smut really lead to such severe sentences? Some netizens have questioned this, speculating that the heavy penalties might actually be due to alleged money laundering or tax evasion. However, these theories were quickly dismissed: the royalties earned by Haitang authors come from legitimate payments made by actual readers, making money laundering unlikely. As for tax evasion, Haitang is a Taiwanese website and isn’t required to pay taxes to the mainland government. Even if mainland authors were guilty of tax evasion, they would likely just be required to pay back taxes rather than face prison time. Relying on these conspiracy theories to justify harsh penalties seems like a way to avoid addressing deeper issues within the current legal system.

Punishment can be actually be heavy based on various other factors. Some netizens have pointed out that the law states that making a profit of 250,000 yuan ($35,000) or achieving over 250,000 clicks is considered an particularly serious offense, potentially leading to a prison sentence of over ten years. But for online writers, especially prominent authors, reaching 250,000 clicks is relatively easy, which put them significantly at risk for for receiving heavy sentencing.

Moreover, the criteria for determining what actually constitutes ‘pornographic materials’ are quite vague. The family of the detained author Li Xin pointed out on Weibo that Article 367 of the Criminal Law specifies that literary and artistic works with artistic value, even if they contain erotic elements, should not be classified as pornographic. While Li Xin’s novels do feature erotic content, they also include a historical, cultural, military, economic, and social insights, leading to a variety of discussions among online readers.

“If this were truly an obscene novel overall, where would such rich discussions have come from?” The family wondered: “While the book does contain some unapologetic depictions of [sexual] relations, they serve only as parts of the story’s progression and character development. Could this limited content really lead to the moral corruption of ordinary people?”

The biggest controversy here centers on the stark contrast between the punishment for writing smut and for committing far more severe crimes. “Ten years is way too long; there are people who commit crimes that truly harm others who don’t face such severe sentences,” one netizen lamented on Weibo in response to Li Xin’s case.

This frustration resonates widely online. According to Chinese law, sentences for rape usually range from 3 to 10 years, with only exceptionally severe cases—such as those involving minors or resulting in serious injury or death—receiving more than ten years.

Angry netizens complain that recent court decisions on heinous crimes like sexual assault, voyeurism, and domestic violence often result in lighter sentences than what Yunjian is facing. Author @LuoSaiEr (@罗塞迩) highlighted a recent case of a man who recorded 75,000 videos for profit over five years and received only a one-year prison sentence. The stark contrast between the punishment for a smut writer and for actual sexual offenders, regardless of the legal complexities, is hard for the public to accept.

In China’s legal circles, there’s a growing belief that the laws around “producing and disseminating pornographic materials for profit” are seriously outdated, with penalties that often don’t align with the actual harm caused to society. Ever since the Tianyi case, legal experts have pointed out that the sentences don’t reflect the realities of today’s world.

Yet for ordinary people who now struggle to find erotic content, discussing legal reform feels almost pointless. With pop-up ads and QR codes linking to porn sites, hidden cameras in hotel rooms, and private videos being sold in group chats, it’s frustrating to see the law come down so hard on smut writers—who have no real victims—while many actual sex offenders walk free. As one netizen put it, this situation “shames the judiciary and makes it look disgraceful.”

Four months later, Yunjian remains in detention. With the support of donations from concerned netizens, her family has overcome their worst financial struggles and no longer accepts contributions. But for them—and for every writer and reader affected by this case—the fight for justice and their right to create still feels like a long, uncertain road ahead.

By Ruixin Zhang

Independently covering digital China for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Arts & Entertainment

Controversial Wanghong Livestreamers Are Becoming a Weibo Staple in China

‘Wanghong’ was a mark of online fame; now, it’s increasingly tied to controversy and scandal.

Published

4 weeks agoon

October 27, 2024

As livestreaming continues to gain popularity in China, so do the controversies surrounding the industry. Negative headlines involving high-profile livestreamers, as well as aspiring influencers hoping to make it big, frequently dominate Weibo’s trending topics.

These headlines usually revolve around China’s so-called wǎnghóng (网红) influencers. Wanghong is a shortened form of the phrase “internet celebrity” (wǎngluò hóngrén 网络红人). The term doesn’t just refer to internet personalities but also captures the viral nature of their influence—describing content or trends that gain rapid online attention and spread widely across social media.

Recently, an incident sparked debate over China’s wanghong livestreamers, focusing on Xiaohuxing (@小虎行), a streamer with around 60,000 followers on Douyin, who primarily posts evaluations of civil aviation services in China.

Xiaohuxing (@小虎行)

On October 15, 2024, at Shenzhen Bao’an International Airport, Xiaohuxing confronted a volunteer at the automated check-in counter, insisting she remove her mask while livestreaming the entire encounter. He was heard demanding, “What gives you the right to wear a mask? What gives you the right not to take it off?” and even attempted to forcibly remove her mask, challenging her to call the police.

During the livestream, the livestreamer confronted the woman on the right for wearing a facemask.

He also argued with a male traveler who tried to intervene. In the end, the airport’s security officers detained him. Shortly after the incident, a video of the livestream went viral on Weibo under various hashtags (e.g. #网红小虎行机场强迫志愿者摘口罩#) and attracted millions of views. The following day, Xiaohuxing’s Douyin account was banned, and all his videos were removed. The Shenzhen Public Security Bureau later announced that the account’s owner, identified as Wang, had been placed in administrative detention.

On October 13, just days before, another livestreaming controversy erupted at Guangzhou Baiyun International Airport. Malatang (@麻辣烫), a popular Douyin streamer with over a million followers, secretly filmed a young couple kissing and mocked them, continuing to film while passing through security—an area where filming is prohibited.

Her livestream quickly went viral, sparking discussions about unauthorized filming and misconduct among Chinese wanghong. In response, Malatang’s agent posted an apology video. However, the affected couple hired a lawyer and reported the incident to the police (#被百万粉丝网红偷拍当事人发声#). On October 17, Malatang’s Douyin account was banned, and her videos were removed.

Livestreamer Malatang making fun of the couple in the back at the airport.

In both cases, netizens uncovered additional examples of inappropriate behavior by Xiaohuxing and Malatang in past broadcasts. For example, Xiaohuxing was reportedly aggressive towards a flight attendant, demanding she kneel to serve him, while Malatang was criticized for scolding a delivery person who declined to interact with her on camera.

Comments on Weibo included, “They’ll do anything for traffic. Wanghong are getting a bad reputation because of people like this.” Another added, “It seems as if ‘wanghong’ has become a negative term now.”

Rising Scrutiny in China’s Wanghong Economy

Xiaohuxing and Malatang are far from isolated cases. Recently, many other wanghong livestreamers have also been caught up in negative news.

One such figure is Dong Yuhui (董宇辉), a former English teacher at New Oriental (新东方) who transitioned to livestreaming for East Buy (东方甄选), where he mixed education with e-commerce (read here). Dong gained significant popularity and boosted East Buy’s brand before leaving to start his own company. Recently, however, Dong faced backlash for inaccurate statements about Marie Curie during an October 9 livestream. He incorrectly claimed that Curie discovered uranium, invented the X-ray machine, and won the Nobel Prize in Literature, among other things.

Considering his public image as a knowledgeable “teacher” livestreamer, this incident sparked skepticism among viewers about his actual expertise. A related hashtag (#董宇辉称居里夫人获得诺贝尔文学奖#) garnered over 81 million views on Weibo. In addition to this criticism, Dong is also being questioned about potential false advertising, which is a major challenge for all livestreamers selling products during their streams.

Dong Yuhui (董宇辉) during one of his livestreams.

Another popular livestreamer, Dongbei Yujie (@东北雨姐), is currently also facing criticism over product quality and false advertising claims. Originally from Northeast China, Dongbei Yujie shares content focused on rural life in the region. Recently, her Douyin account, which boasts an impressive 22 million followers, was muted due to concerns over the quality of products she promoted, such as sweet potato noodles (which reportedly contained no sweet potato). Despite issuing public apologies—which have garnered over 160 million views under the hashtag “Dongbei Yujie Apologizes” (#东北雨姐道歉#)—the controversy has impacted her account and led to a penalty of 1.65 million yuan (approximately 231,900 USD).

From Dongbei Yujie’s apology video

Former top Douyin livestreamer Fengkuang Xiaoyangge (@疯狂小杨哥) is also facing a career downturn. Leading up to the 2024 Mid-Autumn Festival, he promoted Hong Kong Meicheng mooncakes in his livestreams, branding them as a high-end Hong Kong product. However, it was soon revealed that these mooncakes had no retail presence in Hong Kong and were primarily produced in Guangzhou and Foshan, sparking accusations of deceptive marketing. Due to this incident and previous cases of misleading advertising, his company came under investigation and was penalized. In just a few weeks, Fengkuang Xiaoyangge lost over 8.5 million followers (#小杨哥掉粉超850万#).

Fengkuang Xiaoyangge (@疯狂小杨哥) and the mooncake controversy.

It’s not only ecommerce livestreamers who are getting caught up in scandal. Recently, the influencer “Xiaoxiao Nuli Shenghuo” (@小小努力生活) and her mother were arrested for fabricating a tragic story – including abandonment, adoption, and hardships – to gain sympathy from over one million followers and earn money through donations and sales. They, and two others who helped them manage their account, were sentenced to ten days in prison for ‘false advertising.’

Wanghong Fame: Opportunity and Risk

China’s so-called ‘wanghong economy’ has surged in recent years, with countless content creators emerging across platforms like Douyin, Kuaishou, and Taobao Live. These platforms have transformed interactions between content creators and viewers and changed how products are marketed and sold.

For many aspiring influencers, becoming a livestreamer is the first step to building a presence in the streaming world. It serves as a gateway to attracting traffic and potentially monetizing their online influence.

However, before achieving widespread fame, some livestreamers resort to using outrageous or even offensive content to capture attention, even if it leads to criticism. For example, before his account was banned, Xiaohuxing set his comment section to allow only followers to comment, gaining 3,000 new followers after his controversial livestream at Shenzhen Airport went viral. Many speculated that some followers joined just to leave critical comments, but it nonetheless grew his following.

As livestreamers gain significant fame, they must exercise greater caution, as they often hold substantial influence over their audiences, making accuracy essential. Mistakes, whether intentional or not, can quickly erode trust, as seen in the example of the super popular Dong Yuhui, who faced backlash after his inaccurate comment about Marie Curie sparked public criticism.

China’s top makeup livestreamer, Li Jiaqi (李佳琦), experienced a similar reputational crisis in September last year. Responding dismissively to a viewer who commented on the high price of an eyebrow pencil, Li replied, “Have you received a raise after all these years? Have you worked hard enough?” Commentators pointed out that the pencil’s cost per gram was double that of gold at the time. Accused of “forgetting his roots” as a former humble salesman, Li lost one million Weibo followers in a day (read more here).

This meme shows that many viewers did not feel moved by Li’s apologetic tears after the eyepencil incident.

Despite the challenges and risks, becoming a wanghong remains an attractive career path for many. A mid-2023 Weibo survey on “Contemporary Employment Trends” showed that 61.6% of nearly 10,000 recent graduates were open to emerging professions like livestreaming, while 38.4% preferred more traditional career paths.

Taming the Wanghong Economy

In response to the increasing number of controversies and scandals brought by some wanghong livestreamers, Chinese authorities are implementing stricter regulations to monitor the livestreaming industry.

In 2021, China’s Propaganda Department and other authorities began emphasizing the societal influence of online influencers as role models. That year, the China Association of Performing Arts introduced the “Management Measures for the Warning and Return of Online Hosts” (网络主播警示与复出管理办法), which makes it challenging, if not impossible, for “canceled” celebrities to stage a comeback as livestreamers (read more).

The Regulation on the Implementation of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Consumer Rights and Interests (中华人民共和国消费者权益保护法实施条例), effective July 1, 2024, imposes stricter rules on livestream sales. It requires livestreams to disclose both the promoter and the product owner and mandates platforms to protect consumer rights. In cases of illegal activity, the platform, livestreaming room, and host are all held accountable. Violations may result in warnings, confiscation of illegal earnings, fines, business suspensions, or even the revocation of business licenses.

These regulations have created a more controlled “wanghong” economy, a marked shift from the earlier, more unregulated era of livestreaming. While some view these measures as restrictive, many commenters support the tighter oversight.

A well-known Kuaishou influencer, who collaborates with a person with dwarfism, recently faced backlash for sharing “vulgar content,” including videos where he kicks his collaborator (see video) or stages sensational scenes just for attention.

Most commenters welcome the recent wave of criticism and actions taken against such influencers, including Xiaohuxing and Dongbei Yujie, for their behavior. “It’s easy to become famous and make money like this,” commenters noted, adding, “It’s good to see the industry getting cleaned up.”

State media outlet People’s Daily echoed this sentiment in an October 21 commentary, stating, “No matter how many fans you have or how high your traffic is, legal lines must not be crossed. Those who cross the red line will ultimately pay the price.”

This article and recent incidents have sparked more online discussions about the kind of influencers needed in the livestreaming era. Many suggest that, beyond adhering to legal boundaries, celebrity livestreamers should demonstrate a higher moral standard and responsibility within this digital landscape. “We need positive energy, we need people who are authentic,” one Weibo user wrote.

Others, however, believe misbehaving “wanghong” livestreamers naturally face consequences: “They rise fast, but their popularity fades just as quickly.”

When asked, “What kind of influencers do we need?” one commenter responded, “We don’t need influencers at all.”

By Wendy Huang

Follow @whatsonweibo

Edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Subscribe

The ‘Cycling to Kaifeng’ Trend: How It Started, How It’s Going

Hu Xijin’s Comeback to Weibo

Weibo Watch: “Comrade Trump Returns to the Palace”

The Price of Writing Smut: Inside China’s Crackdown on Erotic Fiction

Controversial Wanghong Livestreamers Are Becoming a Weibo Staple in China

“Land Rover Woman” Sparks Outrage: Qingdao Road Rage Incident Goes Viral in China

Weibo Watch: The Land Rover Woman Controversy Explained

Fired After Pregnancy Announcement: Court Case Involving Pregnant Employee Sparks Online Debate

Weibo Watch: Going the Wrong Way

Hidden Hotel Cameras in Shijiazhuang: Controversy and Growing Distrust

China at the 2024 Paralympics: Golds, Champions, and Trending Moments

Weibo Watch: Small Earthquakes in Wuhan

Death of Chinese Female Motorcycle Influencer ‘Shigao ProMax’ Sparks Debate on Risky Rides for Online Attention

Why the “人人人人景点人人人人” Hashtag is Trending Again on Chinese Social Media

The Hashtagification of Chinese Propaganda

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight7 months ago

China Insight7 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music8 months ago

China Music8 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Insight12 months ago

China Insight12 months agoThe Story of Li Jun & Liang Liang: How the Challenges of an Ordinary Chinese Couple Captivated China’s Internet