China Books & Literature

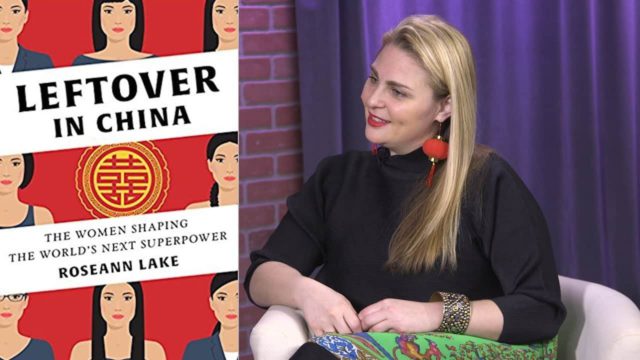

Leftover in China: The Women Shaping the World’s Next Superpower by Roseann Lake

In a new book on China’s Leftover Women, author Roseann Lakes highlights the strength and merit of China’s unmarried women.

Published

7 years agoon

With Leftover in China – The Women Shaping the World’s Next Superpower, author Roseann Lake brings a deeply insightful and captivating account of China’s so-called ‘leftover women’ – the unmarried females who are shaping the future of the PRC. A must-read book for this Spring Festival holiday.

As the count-down for China’s most important event of the year, the Spring Festival, has started, countless unmarried daughters and sons anticipate the reunion with their parents and relatives with some horror. “Why are you still single?” is amongst the top-dreaded questions they are facing during the New Year’s dinners at the family dining table.

More so than the bachelor sons, it’s China’s unmarried daughters in their late twenties and early thirties who came to be at the center of a media storm over the past decade. The so-called ‘leftover women’ (剩女 shèngnǚ) have become a source of critique, banter, worry, fascination, and inspiration for the media, both in- and outside China.

The term shèngnǚ became a catchphrase ever since the Chinese Ministry of Education listed it as one of the newest additions to Chinese vocabulary in 2007. The shengnü label is mainly applied to unmarried (urban) women in their late twenties or early thirties who are generally well-educated and goal-oriented, but who came to be associated with ‘leftover food’ because of their single status and long-standing beliefs about the right age to marry.

One 2015 survey by Chinese dating site Zhenai, that was held amongst 1452 single men and women, shows that 50% of Chinese men think that women who are still single at the age of 25 are ‘leftovers.’

SILVER LININGS

“I’m pro-active about finding a partner, but not to the extent that it gets in the way of other ambitions.”

After the success of much-acclaimed books such as Factory Girls (Leslie T. Chang 2008) and Leftover Women: The Resurgence of Gender Inequality in China

(Leta Hong Fincher 2014), Leftover in China: The Women Shaping the World’s Next Superpower (2018) by Roseann Lake, Cuba correspondent for The Economist, brings fresh insights into the role and position of young women in a rapidly-changing society.

At the root of the ‘leftover women’ phenomenon and the media frenzy around it lies China’s One-Child Policy (1979-2015), the country’s imbalanced sex ratio, and traditional perceptions on wives and mothers being the building blocks of Chinese families and the nation at large.

Leftover in China is Roseann’s Lake first (non-fiction) book.

Lake describes how the onset of China’s One-Child Policy and a traditional preference for sons, together with the available ultrasound technology in the late 1980s, led to an enormous rise of abortions on female fetuses. The gender imbalance it brought about is most severe in China’s rural areas; in places such as Tianmen, Hubei, the gender ratio is a shocking 176 males to 100 females. It leaves villages full of men who are unable to find a bride and start a family. Guānggùn (光棍), they’re also called, literally the “bare branches” of their hometowns.

While the ‘bare branches’ reside in China’s more rural areas, the ‘leftover women’ live in China’s more urban areas. The ‘bare branches’ and ‘leftover women’ both have difficulties in finding a partner, albeit for radically different reasons. For the rural men, there simply are not enough marriage candidates, whereas for the urban women, there are not enough suitable marriage candidates. A major difference between the countryside and the urban environment is that China’s cities have seen a much better-balanced gender ratio, with parents pampering and pressuring their only child – whether it was a boy or girl.

Although Lake does explain the “gruesome cloud” of China’s One-Child Policy and female foeticide and the demographic problems it has triggered, she especially focuses on the “silver lining,” which is that the sociopolitical circumstances have also ‘forced’ parents to value their daughters more than ever before. Over the past decades, millions of Chinese daughters have been given the opportunities and liberties their mothers and grandmothers never had. Their increased educational and professional prospects have made marriage somewhat less of a priority for them.

While China’s unmarried, urban woman are often stigmatized by Chinese state media for being too ‘spoilt’, ‘picky’, or ‘promiscuous’ to marry, Roseann Lake casts an entirely different light on China’s urban bachelorettes as being determined, independent, and self-assured. “I’m pro-active about finding a partner,” one of the ‘leftover women’ in Lake’s book says: “But not to the extent that it gets in the way of other ambitions.”

CHANGING TIMES, CHANGING LOVE

“Leftover women are resisting ultimatums to wed because they want to marry for love, and not just for the sake of being married.”

Lake’s strong connection to Chinese culture and society jumps off the pages of Leftover in China, in which she playfully and compellingly offers a window into the female experience in modern China, explaining fascinating concepts that are unique to modern-day society. One such example is the ‘phantom third stories’ phenomenon; two-story houses with an unfinished ‘fake’ third story, built by unmarried men and their family to make the house appear more grandiose in the hopes of attracting a wife.

The interest in China started when Lake took a sabbatical from her job with the French government in New York, and went to Beijing. “I was only supposed to stay for three months,” she tells What’s on Weibo: “But shortly into my stay I bought a hot orange electric – Chinese – ‘Vespa’, and that changed everything.”

Journalist Roseann Lake.

As Lake was riding her scooter, which she lovingly nicknamed ‘Fanta’, she took in the city and all of its aspects, including its love and romantic relationships. On what first caught her attention within this field, she explains that it started one afternoon as she was riding her scooter in Beijing and spotted a very angry Chinese woman on the side of the road, screaming profanities at a man who appeared to be her romantic partner. The altercation turned violent, and it was not the first time Lake had witnessed such a scene between couples in public.

“I felt that something seemed afoul with the state of romantic relationships in China,” she says – which was a start of her interest and research into romance, love, and the role of Chinese women in this. “For thousands of years, marriage has largely been a mercenary, transactional agreement in China, made with the best interests of the key stakeholders – the parents – in mind.”

Romantic love as a reason for marriage in China, Lake says, is a relatively new concept. She tells What’s on Weibo: “Down the line, this better helped me understand the situation of leftover women – many of which, as I discovered, were resisting ultimatums to wed because they wanted to marry for love, and not just for the sake of being married.”

The topic of China’s changing marriage values and the generation gap in perceptions on love and marriage between parents and their daughters recurringly comes back in Lake’s book, for which she followed the lives of various ‘leftover women’ over a period of several years. Through the stories of women such as Christy, the CEO of a successful Beijing PR firm, or June, a “return turtle” who came back to the mainland after graduating from Yale, readers can get a grasp of the pressures and problems many single women are facing in China today.

An important lesson to draw from this book is that the phenomenon of China’s ‘leftover women’ cannot be explained through a unidimensional lens. Lake highlights China’s historical, societal, cultural, and economic dimensions in her approach of why this large group of unmarried women, despite all of their personal, academic and professional achievements, are still being labeled through their single status.

THE TOAST OF THE NATION

“There is irony and absurdity in the fact that these women are referred to as “leftover” but are really such an important part of China’s future.”

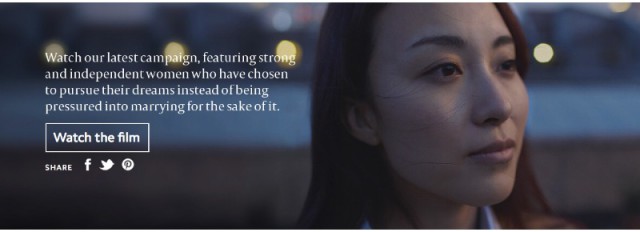

In 2016, an ad campaign by skincare brand SK-II titled ‘She Finally Goes to the Marriage Corner’ (她最后去了相亲角) gained huge popularity on Chinese social media. The short video showed how women, pressured to get married by their families and society, pluck up the courage to speak out and get their message heard.

The video received much praise, with many women protesting against the derogatory ‘leftover women’ label. CCTV recently also posted a feature article on social media in which various women plead for the elimination of the “leftover woman” or shèngnǚ label.

Why, then, would Lake still refer to the ‘leftover’ label on the cover of her book? About the book’s title, Lake says: “There was a different title that I preferred, but my publisher disagreed with it, so we compromised on ‘Leftover in China.’ It has grown on me. I’m told that for non-fiction books, the subtitle is just as important as the title itself, and I think “The Women Shaping the World’s Next Superpower” is apt. It underscores the irony and absurdity of the fact that these women are referred to as “leftover” but are really such an important part of China’s future.”

Throughout the course of writing this book, Lake spoke to many experts on the importance of China’s young (unmarried) women in shaping Chinese economics. One of them is Dr. Kaiping Peng, the founding chair of the Department of Psychology at Tsinghua University, who is quoted as saying: “The Chinese economic miracle has two secrets. The first are migrant workers, and the second are young, educated women.”

All the love, time, and money that Chinese parents and grandparents have invested in their only (grand)daughter has now paid off – not just for them, but for the economy at large. These well-educated and hard-working women play a powerful role in running China’s economic engine.

THE FUTURE OF CHINA’S LEFTOVER WOMEN

“Few people know that the most imbalanced year for sex ratio at birth in China was actually 2005.”

When talking about the future of China’s ‘leftover women,’ Lake suspects that they will continue to get married later in life or not at all – on trend with what is also happening in countries such as Japan or South Korea. “This would be much to the dismay of the Chinese government” Lake says, “- which desperately wants babies, but hasn’t done much to incentivize or make it easier for women to have them.”

Social media platforms such as Weibo and WeChat also play an important role in the lives of these women: “When I was living in China and writing the first drafts of this book, there were a few groups on Weixin [WeChat] where women would chat, share articles, and plan gatherings. They’ve dramatically multiplied! More content is shared, more ideas are exchanged, and the ease of these platforms means that Chinese women abroad can easily remain a part of the conversation.”

Lake is more worried about the so-called guānggùn, China’s ‘bare branches’: “We all may imagine that the worst years for gendercide were in the 80s and 90s, when population controls were stricter in China, but I think few people know that the most imbalanced year for sex ratio at birth in China was actually 2005. That means that boys who are now 13 years old will likely have a harder time finding a wife than any generations of men before them.”

This Spring Festival, Lake is anticipating the launch of her book (release February 13, 2018), which has already been listed as one of the must-read books for 2018 by the South China Morning Post.

For China’s many bachelorettes, they’ll just have to face the nagging questions at the New Year’s dining table, but they need not worry too much about being called ‘leftover women.’ Through books such as these, the term loses its derogatory tone – it is becoming a badge of honor instead.

Leftover in China: The Women Shaping the World’s Next Superpower by Roseann Lake is now available for pre-sale:

Get on Amazon: Leftover in China: The Women Shaping the World’s Next Superpower

Get on iTunes: Leftover in China: The Women Shaping the World’s Next Superpower

Get on Book Depository: Leftover in China: The Women Shaping the World’s Next Superpower

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2018 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Arts & Entertainment

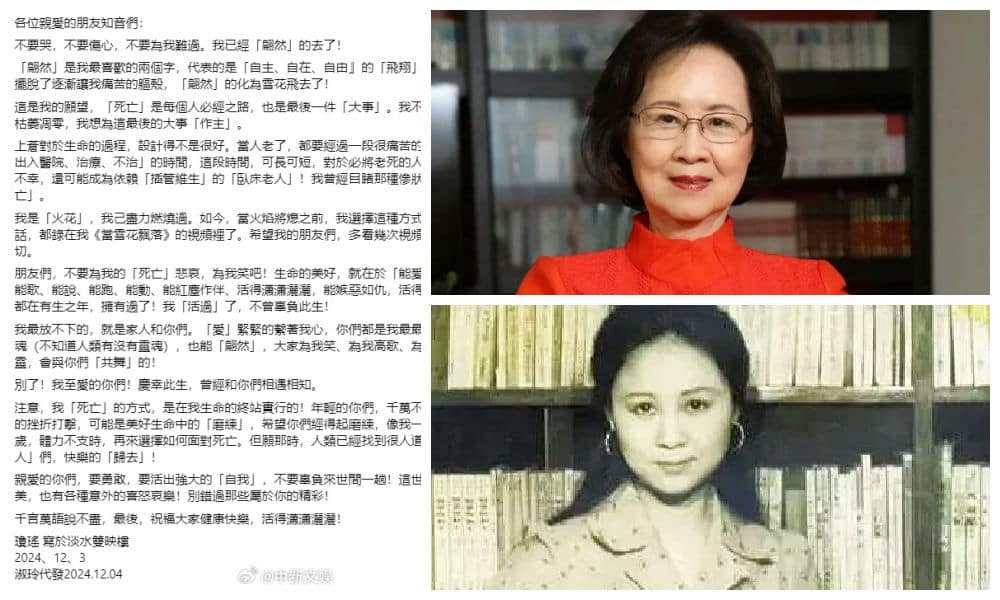

Chiung Yao’s Suicide Farewell Letter: An English Translation

Published

3 months agoon

December 7, 2024

Chinese netizens mourned the passing of Taiwanese writer Chiung Yao (琼瑶) this week. Chiung Yao, one of China’s most beloved romance novelists, passed away at the age of 86.

Among her many works, Chiung Yao is cherished by many netizens in mainland China as part of their collective memories from the 1980s and 1990s. Some of the most iconic Chinese dramas, such as My Fair Princess (also: Return of the Pearl Princess, 還珠格格), were written by Chiung Yao.

On December 4, she was found on her sofa at home, leaving behind a suicide note. The cause of death was determined to be asphyxiation due to carbon monoxide poisoning.

In her farewell letter to loved ones and fans, she wrote the following:

“To all my dear friends:

Do not cry, do not grieve, and do not feel sad for me. I have already fluttered away [翩然 piānrán] effortlessly.

I love the word “翩然” [piānrán]. It represents flying in the air independently, easily, and freely. Elegantly and gracefully, I have shed the body that gradually caused me pain and have ‘fluttered away,’ transforming into snowflakes flying into the sky.

This was my wish. “Death” is a journey everyone must take—it is the final significant event in life. I did not want to leave it to fate, nor did I want to wither away slowly. I wanted to have the final say in this final event.

God has not designed the process of life particularly well. When a person grows old, they have to go through a very painful period of ‘becoming weak, degeneration, illness, hospitalization, treatment, and fatal illness.’ This period, may it be long or short, is a tremendous torment for those who are destined to grow old and die! Worst of all, some may become bedridden, dependent on tubes for survival. I have witnessed such tragedies, and I do not want that kind of “death.”

I am a “spark,” and I have already burned as brightly as I could. Now, before the flame finally dims, I have chosen this way to make a light departure. I have recorded everything I wish to say in my video “When Snowflakes Fall Down” (当雪花飘落). I hope my friends can watch it a few times to grasp everything I wanted to express.

Friends, do not mourn my death but smile for me! The beauty of life lies in the ability to love, hate, laugh, cry, sing, speak, run, move, be together until death parts us, live freely, despise evil with a passion, and live life boldly. I have experienced all these things in my lifetime! I truly ‘lived’ and did not waste this life.

What I find hardest to let go of are my family and all of you. “Love” is what is tightly bound to my heart, and I am reluctant to part with you. To allow my soul (if humans even have souls) to also ‘flutter away,’ please laugh for me, sing loudly for me, and dance in the breeze for me! My spirit in the heavens will dance together with you!

Farewell, my dearest ones! I am grateful for this life, where I had the chance to meet and know you all.

Take note of the way I died: I was at the final station of my life! For those of you who are still young, never give up on life lightly. Momentary setbacks or blows may be the “training” for a beautiful life. I hope you will be able to endure those, as I did, and live to 86, 87.. years old. When your physical strength fades, then decide how to face death. By then, perhaps they will have found more humane ways to help the elderly “leave joyfully.”

Dear friends, be brave, be the greatest version of yourself. Do not waste your journey through this world! Though this world is not perfect, it is filled with unexpected joys, sorrows, and laughter. Don’t miss out on all the wonders out there for you.

There are a thousand more things to say, but in the end, I wish everyone health, happiness, and a life of freedom and joy.”

This translation was previsously published on my X channel here.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Books & Literature

The Price of Writing Smut: Inside China’s Crackdown on Erotic Fiction

The crackdown on Haitang Literature City has led to greater awareness of it, with Chinese netizens now paying closer attention to the repression of erotic content and the struggles faced by its authors.

Published

4 months agoon

November 3, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

A recent crackdown on Chinese authors writing erotic webnovels has sparked increased online conversations about the Haitang Literature ‘Flower Market’ subculture, the challenges faced by prominent online smut writers, and the evolving regulations surrounding digital erotica in China. But how serious is the “crime” of writing explicit fiction China today?

You might have heard of haitang (海棠), the Chinese crabapple flower, but chances are you haven’t come across Haitang Literature City (海棠文学城)—and you’re not alone. Most people in China haven’t heard of it either. Haitang Literature City is a Taiwan-based, Chinese-language website dedicated primarily to female-oriented smut fiction, with numerous contributors from mainland China.

‘Smut fiction’ is a genre focused on explicit, sexual content and themes. Stories in this genre often emphasize the physical relationships between characters, with detailed erotic scenes. On Haitang Literature City, the most popular category is BL (Boys’ Love), which centers on romantic and erotic relationships between male characters and is written mainly for a female audience (read more here). The site also features a variety of heterosexual and lesbian stories, ranging from straightforwardly explicit to more unusual narratives. One consistent aspect across the site: most of the authors are women, writing primarily for a female readership.

Example covers of online erotica

Haitang Literature City, known as the ‘Flower Market’ (花市) by its users, has stayed relatively underground within certain reading circles. Recently, however, a help post on Weibo has brought this hidden flower market into the spotlight, sparking considerable buzz online.

The post came from a user named “Rain Painted on a Sunny Day” (@晴天画的雨), the younger sister of the Haitang author known as “Yunjian” (云间, “Between the Clouds”). On October 16, she revealed that Yunjian had been detained since June 20 and is only allowed visits from her lawyer. The arrest notice she shared cites the charge: “suspected of producing and disseminating pornographic materials for profit” (“传播淫秽物品牟利罪”).

Yunjian, a prominent author on Haitang, has been writing for over a decade, producing tens of millions of words. Her detention not only forces her to forfeit all the royalties earned over the past ten years—now labeled “illicit earnings”—but also means she faces time in prison. While “Rain Painted on a Sunny Day” acknowledged her sister’s “offense” in the post, she explained that the resulting heavy fines have left their family deeply in debt, struggling to make ends meet. After the post went up, many of Yunjian’s readers expressed heartbreak over her situation and began donating to help.

Meanwhile, Haitang Literature City, once part of an underground culture, has been brought into the spotlight. “What is Haitang Literature City? Why are the authors on this site charged with the crime of producing and distributing obscene materials? Can someone explain? It feels like a completely different world—I truly have no idea about any of this,” one Weibo user wrote. Ironically, the crackdown on the site has led to greater awareness of it, with Chinese netizens now paying closer attention to the long-standing repression of erotic content authors and the ongoing struggles they face.

MONTHS OF CRACKDOWN

“They’re back to where they started, with nothing to their name”

The crackdown on authors of explicit content from Haitang Literature City began earlier in 2024. Blogger @LXC (@洛曐曟LXC), who has been documenting these events, described how police in Anhui Province launched a cross-provincial operation in June. On June 20, they arrested Haitang distributors along with several of its most successful authors. The Haitang site quickly shut down the next day, citing maintenance. The platform remained offline for several days.

During this shutdown, many authors aware of the arrests requested that their published work be hidden. As a result, Haitang locked down all site content, allowing authors to unblock their works only upon request.

Most of the first batch of arrested authors were released around June 20, with some warning others against writing on Haitang due to the high risks involved. However, this information circulated only within a small group, so few were aware of it. Authors who had earned larger sums from their writing were unable to arrange their release and remained in custody.

How did Haitang respond? Despite being aware of the arrests, the site apparently chose not to inform other authors of the risks, possibly prioritizing profits and readership. Blogger @LXC expressed her frustration with Haitang for misleading authors who were completely unaware of the situation, as well as others who had heard unverified rumors, into unlocking their columns for subscriptions. Seeing this, several smaller authors followed suit and unlocked their works as well.

From late July to early August, another group of authors was summoned by the police. Nearly all of this second batch of arrested authors were among those who had reapplied to unblock their columns after the site had reopened. LXC suggested that the site’s mismanagement and silence about the initial arrests were responsible for these authors getting into trouble.

Yunjian remains one of the authors detained since the initial crackdown in June and has yet to be released. Alongside her, many lesser-known authors are also struggling, with many relying on their writing on Haitang to make ends meet. Among them are stay-at-home moms, low-income students, and young women from rural areas who cannot find work. After all this upheaval, their situations have only worsened, and they are likely in even more dire straits than the more well-known authors.

“To me, it’s straightforward,” @LXC wrote: “These women earned money and, as a result, improved their previously poor lives. Now that money is being taken away from them, they’re back to where they started, with nothing to their name.”

A DECADE-LONG SURVIVAL GAME

“Censorship has reached absurd levels”

This isn’t the first time Chinese online smut writers have been targeted under the country’s strict censorship laws governing pornographic content. Since China launched its “Clean Internet Campaign” in 2014, many smut writers and online fiction platforms have faced consequences. In June 2015, author Ding Yi (丁一) received a suspended three-and-a-half-year sentence for her “explicit” novels on the platform Jinjiang Literature City (晋江文学城). Another writer, Mo Xiang Tong Xiu (墨香铜臭), known for her novel The Untamed and its TV adaptation, was sentenced to three years on “illegal publishing” charges. Although her case didn’t specifically involve “producing and disseminating pornographic materials for profit,” her arrest was still part of the broader anti-pornography campaign due to the erotic themes in her work.

Another well-known BL writer, Tian Yi (天一), faced an even harsher punishment. In 2018, she was sentenced to ten and a half years in prison for her novel Absolute Domination, which included erotic depictions of gay relationships and had earned her around 150,000 yuan ($21,000) from print sales. A young woman who assisted with typesetting was also implicated—she received a four-year sentence and a 10,000-yuan ($1,400) fine for her 3,100-yuan ($430) part-time payment.

While authors have faced relentless crackdowns, websites themselves have also struggled to survive. Jinjiang Literature City (晋江文学城)—a major online fiction platform known for hosting works with mature content—has been shut down and pressured into strict content checks, with some smaller sites shut down entirely. After multiple shutdowns and rounds of scrutiny, Jinjiang became almost hyper-vigilant, enforcing its self-censorship to an extreme. Now, any sensitive terms are automatically replaced with “口口,” as the site pushes to remove anything that might be seen as explicit by the authorities.

Many netizens have pointed out that the “content review guidelines” (link) of the Jinjiang platform are ironically hilarious: “Any depiction below the neck involving intimacy, body parts, sexual acts, sexual thoughts or fantasies, sexual organs, or excessive violence is considered explicit and thus prohibited,” it states. “Even if it’s less direct and more subtle, if the scenes are too lengthy or portray the entire process, they are also counted as explicit content.” Netizens joke that as long as the reviewers think you’re being suggestive, it’s a off limits—censorship has reached absurd levels.

However, readers’ demand for pornographic works hasn’t diminished at all in this decade-long, intense survival game. A quick search for names like “Tian Yi,” “Yunjian,” or “Mr. Shenhai” on Weibo still reveals hundreds, if not thousands, of people actively seeking and sharing resources for their novels.

THE PRICE OF EROTIC CONTENT IN CHINA

“There are people who commit crimes that truly harm others who don’t face such severe sentences”

How serious is the “crime” of writing online smut in China? While Yunjian has yet to be tried or sentenced, online discussions suggest she may face severe punishment. Her royalties over the past decade exceed 250,000 yuan ($35,000), potentially classifying her case as a particularly serious offense under Chinese law for “producing and disseminating pornographic materials for profit,” due to its perceived negative impact on youth and potential to corrupt social morals. This could result in fines of one to five times her earnings and likely a prison sentence of over ten years.

Recent cases indicate similar outcomes: on October 17, a Weibo account called @HuaiBeiLiXinWrongfulCase (@淮北李鑫冤案) posted a plea, revealing that author Li Xin (李鑫), who co-wrote the historical fantasy Six Dynasties with Luo Sen (罗森), was detained on the same charge after earning 300,000 yuan ($42,118) in royalties, which led to a ten-year prison sentence. As a similarly prominent author, Yunjian may face even harsher penalties and potentially an even longer prison term.

🌟 Attention!

For 11 years, What’s on Weibo has remained a 100% independent blog, fueled by our passion to write about China’s digital culture and online trends. Over a year ago, we introduced a soft paywall to ensure the sustainability of this platform. We’re grateful to all readers who’ve subscribed since 2022. Your support has been invaluable. But we need more subscribers to continue our work. If you appreciate our content and want to support independent coverage on digital China, please become a subscriber today. Your support keeps What’s on Weibo going strong!

Can writing smut really lead to such severe sentences? Some netizens have questioned this, speculating that the heavy penalties might actually be due to alleged money laundering or tax evasion. However, these theories were quickly dismissed: the royalties earned by Haitang authors come from legitimate payments made by actual readers, making money laundering unlikely. As for tax evasion, Haitang is a Taiwanese website and isn’t required to pay taxes to the mainland government. Even if mainland authors were guilty of tax evasion, they would likely just be required to pay back taxes rather than face prison time. Relying on these conspiracy theories to justify harsh penalties seems like a way to avoid addressing deeper issues within the current legal system.

Punishment can be actually be heavy based on various other factors. Some netizens have pointed out that the law states that making a profit of 250,000 yuan ($35,000) or achieving over 250,000 clicks is considered an particularly serious offense, potentially leading to a prison sentence of over ten years. But for online writers, especially prominent authors, reaching 250,000 clicks is relatively easy, which put them significantly at risk for for receiving heavy sentencing.

Moreover, the criteria for determining what actually constitutes ‘pornographic materials’ are quite vague. The family of the detained author Li Xin pointed out on Weibo that Article 367 of the Criminal Law specifies that literary and artistic works with artistic value, even if they contain erotic elements, should not be classified as pornographic. While Li Xin’s novels do feature erotic content, they also include a historical, cultural, military, economic, and social insights, leading to a variety of discussions among online readers.

“If this were truly an obscene novel overall, where would such rich discussions have come from?” The family wondered: “While the book does contain some unapologetic depictions of [sexual] relations, they serve only as parts of the story’s progression and character development. Could this limited content really lead to the moral corruption of ordinary people?”

The biggest controversy here centers on the stark contrast between the punishment for writing smut and for committing far more severe crimes. “Ten years is way too long; there are people who commit crimes that truly harm others who don’t face such severe sentences,” one netizen lamented on Weibo in response to Li Xin’s case.

This frustration resonates widely online. According to Chinese law, sentences for rape usually range from 3 to 10 years, with only exceptionally severe cases—such as those involving minors or resulting in serious injury or death—receiving more than ten years.

Angry netizens complain that recent court decisions on heinous crimes like sexual assault, voyeurism, and domestic violence often result in lighter sentences than what Yunjian is facing. Author @LuoSaiEr (@罗塞迩) highlighted a recent case of a man who recorded 75,000 videos for profit over five years and received only a one-year prison sentence. The stark contrast between the punishment for a smut writer and for actual sexual offenders, regardless of the legal complexities, is hard for the public to accept.

In China’s legal circles, there’s a growing belief that the laws around “producing and disseminating pornographic materials for profit” are seriously outdated, with penalties that often don’t align with the actual harm caused to society. Ever since the Tianyi case, legal experts have pointed out that the sentences don’t reflect the realities of today’s world.

Yet for ordinary people who now struggle to find erotic content, discussing legal reform feels almost pointless. With pop-up ads and QR codes linking to porn sites, hidden cameras in hotel rooms, and private videos being sold in group chats, it’s frustrating to see the law come down so hard on smut writers—who have no real victims—while many actual sex offenders walk free. As one netizen put it, this situation “shames the judiciary and makes it look disgraceful.”

Four months later, Yunjian remains in detention. With the support of donations from concerned netizens, her family has overcome their worst financial struggles and no longer accepts contributions. But for them—and for every writer and reader affected by this case—the fight for justice and their right to create still feels like a long, uncertain road ahead.

Update December 2024 (taken from our Newsletter):

We wanted to provide some updates about the erotic content writers we discussed previously, as their final sentencing results were announced recently. One of the authors convicted is Yunjian (云间), one of the more prominent writers of these sexually explicit web novels. As reported by Lianhe Zaobao, she was sentenced to 4 years and 6 months in prison for profiting from illegal activities. Some authors who were unable to gather funds to return illicit gains faced even longer sentences.

On Weibo, some people are outraged over the severity of the punishment, especially since Yunjian reportedly earned no more than 2 million RMB ($275,000) over several years of publishing. However, there are also some who defend the state’s crackdown on online “obscenities,” arguing that distributing such explicit content is a serious crime.

One commenter on Weibo wrote: “I don’t want to describe works filled with hope as ‘obscene materials’ (淫秽物品). I don’t want to define the hard-earned income from creative efforts as ‘illegal earnings’ (赃款). I don’t want to reduce the warm and joyful exchanges between readers and authors to the act of ‘distributing obscene materials’ (传播淫秽物品). This is the most degrading and evil form of humiliation.”

By Ruixin Zhang

Independently covering digital China for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

What’s on Weibo Chapters

Subscribe

Five Trending Proposals at the Two Sessions 🔍

US-Russia Rapprochement and “Saint Zelensky”: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Shake-Up

“Li Jingjing Was Here”: Chinese Netizens React to Rumors of “Chinese Soldiers” in Russian Army

How Ne Zha 2’s Shen Gongbao Became Known as the Ultimate “Small-Town Swot”

Beyond the Box Office: What’s Behind Ne Zha 2’s Success?

Our Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Why Chinese Hit Movie “Her Story” is ‘Good Stuff’: Stirring Controversy and Celebrating Female Perspectives

Chiung Yao’s Suicide Farewell Letter: An English Translation

12-Year-Old Girl from Shandong Gets Infected with HPV: Viral Case Exposes Failures in Protecting Minors

Weibo Watch: Christmas in China Is Everywhere and Nowhere

Breaking the Taboo: China’s Sanitary Pad Controversy Sparks Demand for Change

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

Weibo Watch: China’s Online Feminism Is Everywhere

Story of Chinese Female MA Graduate Going Missing for 13 Years Sparks Online Storm

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight10 months ago

China Insight10 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music11 months ago

China Music11 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital9 months ago

China Digital9 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

-

China Arts & Entertainment10 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment10 months agoSinging Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Oi-lin

February 20, 2018 at 1:24 pm

Curious that this white author’s book does not reference Leta Hong Fischer’s pioneering work.

Sigrid

May 7, 2018 at 7:04 am

Because Leta Hong Fingers book is irrelevant to the topics dealt with in Lake’s book.