China Media

No Hashtags for Mahsa Amini on Chinese Social Media

“Why is that every time Mahsa Amini is mentioned, it somehow gets linked to America?”

Published

3 years agoon

While the death of Mahsa Amini and the unrest in Iran is a major news story worldwide, the incident and its aftermath received relatively little attention in Chinese media, where the narrative is more focused on how Western responses to the issue are intensifying anti-American sentiments within Iran.

Her name in Chinese is written as 玛莎·阿米尼, Mǎshā Āmǐní. Mahsa Amini is the young Iranian woman whose death made international headlines this month and triggered social unrest and fierce protests across Iran for the past ten days, killing at least 41 people.

The 22-year-old Amini was arrested by morality police in Tehran on 16 September for allegedly not wearing her hijab according to the mandatory dress code for women while she was visiting the city together with her family. According to eyewitness accounts, Amini was severely beaten by officers before she collapsed and was taken to the hospital where she died three days later.

The protests following Amani’s death were visible in the streets, but also on social media where Iranian women posted videos of themselves cutting off their hair as a sign of mourning and protest, asking others to help raise awareness on Amini’s death and violence against women amid internet shutdowns in the country.

There were also protests outside of Iran in other places across the world. In London, protesters clashed with police officers during a demonstration outside the Iranian embassy on Monday.

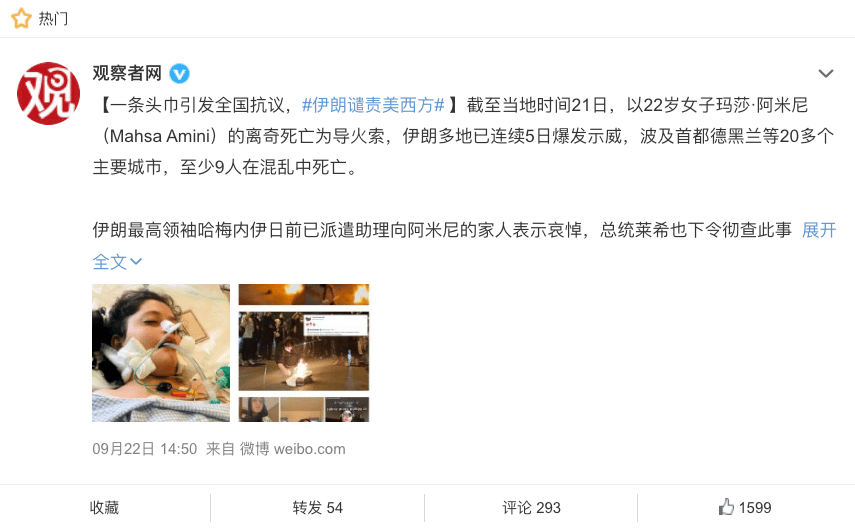

On Chinese social media platform Weibo, Chinese news site The Observer (观察者网) reported Amini’s death and the ensuing protests on September 22, but the hashtag selected to highlight the post did not focus on Amini.

Instead, it emphasized the reaction of the Iranian Foreign Ministry, which accused the United States and other Western countries of using the unrest as an opportunity to interfere in Iran’s internal affairs (hashtag: “Iran Denounces the US and other Western Countries #伊朗谴责美西方#).

The hashtag decision is noteworthy and also telling of how the developments in Iran have been reported by Chinese (online) media sources, which evade the topic of anti-government protests and instead focus on pro-regime marches and anti-American sentiments.

On China’s Tiktok, Douyin, as well as on Weibo, the Chinese media outlet iFeng News posted a video showing Iranian pro-government, anti-American protests on September 25, featuring interviews with veiled women speaking out in support of their country and showing “down with America” slogans and people burning the American flag.

In the comment sections, however, people were critical. One of the most popular comments said: “It must have been difficult organizing all these people.” Another person wrote: “Ah now I am starting to understand that it must have been Americans who beat the girl to death for not properly wearing her hijab.”

But there were also Chinese netizens who said that Iran was seeing a “color revolution” (颜色革命) initiated by the West, suggesting that foreign forces, mainly the U.S., are trying to get local people to cause unrest through riots or demonstrations to undermine the stability of the government.

China Daily also published a video on Douyin in which they featured Iranian political analyst Foad Izadi who said that the demonstrators in Iran could be divided into two groups: one group cared about “a young woman losing her life,” but a second group are people “linked to terrorist organisations based outside Iran.”

Chinese media commentator Zhao Lingmin (赵灵敏) posted a video in which she spoke about the situation in Iran and provided more background information on the history of the country, during which she noted how one Iranian official had supposedly said that “the only two civilizations in Asia worth mentioning are Iran and China.”

Zhao explained how Iran officially became the Islamic Republic in April of 1979 as 98.2% of the Iranian voters voted for the establishment of the republic system in a national referendum.

Videos using the Douyin hashtag “Iran’s Amini” (#伊朗阿米尼) were seemingly taken offline while various images included in Weibo posts about Mahsa Amini and the unrest in Iran were also censored.

“It’s good that we can follow the situation here [on this account], because it’s been removed at others,” one commenter said in response to one post about the many protests following the young woman’s death.

Searches for Amini’s name came up with zero results on the website of Chinese state media outlets CCTV and Xinhua, where the last article about Iran was about how Iranian people think “America can’t be trusted.”

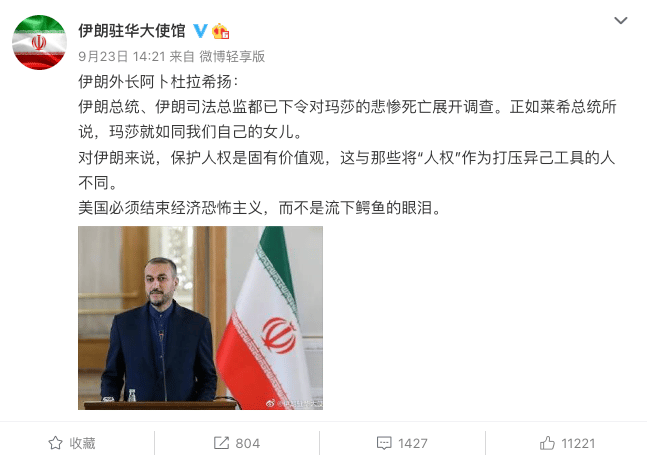

The official Weibo account of the Iranian Embassy in China did post a statement about Amini on September 23, writing that Iranian authorities have ordered an investigation into her tragic death and that the protection of human rights is an intrinsic value to Iran, “unlike those who use ‘human rights’ as a tool to suppress others.” “America must end its economic terrorism instead of shedding crocodile tears,” the last line said. That post received over 11,000 likes.

“Why is that everytime the Mahsa incident is mentioned, it somehow gets linked to America?!” one popular comment said, with another person also responding: “Sure enough, the U.S. gets blamed for everything.”

“So it was the Americans who killed her?” some Chinese netizens sarcastically wrote in response to the post by The Observer, which also mentioned the U.S. in their report of Mahsa’s death.

“I don’t know the exact circumstances, but I support the right of women not to wear a veil,” others said. “Men and women are equal, women should have the freedom to wear what they want and have education and get a job and have some fun,” another Weibo commenter wrote.

One Zhejiang-based Weibo user wrote: “The courage of people marching in the streets for freedom is moving. I wish that women will no longer have their freedom restricted through a hijab. What will the 21st century look like? The answer is still blowing in the wind.”

By Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our weekly newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2022 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Insight

From Trade Crisis to Patriotic Push: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Tariffs

“This moment is the time to reflect on our unity. If we can choose domestic alternatives, we should.”

Published

1 week agoon

April 5, 2025

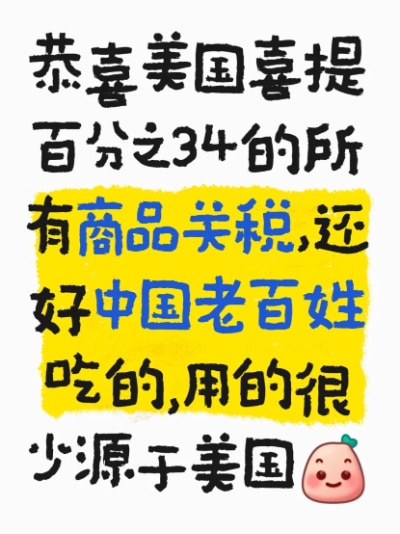

“China’s countermeasures are here” (#中方反制措施来了#). This hashtag, launched by Party newspaper People’s Daily, went top trending on Chinese social media on Friday, April 4, after President Trump announced steep new tariffs on Wednesday, including a universal 10 percent “minimum base tariff” on all imported goods and especially targeting China with an additional 34% reciprocal tariff as part of so-called “liberation day.”

Countermeasures were announced on Friday. China’s State Council Customs Tariff Commission Office (国务院关税税则委员会办公室) issued an announcement stating that, starting from April 10, an additional 34% tariff will be levied on all imported goods originating from the United States, on top of existing tariff rates.

Other countermeasures include immediate export restrictions on seven key medium to heavy rare earth elements, which are important for manufacturing critical products used in semiconductors, defense, aerospace, and green energy.

“This won’t make America great again”

The official response to the tariffs, both from state media and the government, has been twofold: on the one hand, it criticizes the U.S. for placing American interests above the good of the global community, arguing that the move only hurts the U.S., its people, and the world. On the other hand, the Chinese side stresses that although they do not believe tariff wars are the answer, China is not afraid of a trade war and will not sit idly by, but will respond with equal measures.

Chinese official media have condemned the new tariffs, which led to the largest single-day market drop in years. Describing the reactions of various experts, Xinhua News highlighted a comment by a Croatian professor, stating that the policy will only increase export prices and worsen inflation, ultimately hurting middle- and working-class Americans — and noting that the policy “won’t make America great again” (不会“让美国再次伟大”).

The official announcement by Chinese state media regarding China’s countermeasures received widespread support in its (highly controlled) comment sections, with both media outlets and netizens echoing the message that China will not be bullied by the U.S.

On Xiaohongshu, similar sentiments shnone through in popular posts, such as one person writing:

💬 “Congratulations to the U.S. on receiving a 34% tariff on all its goods! Luckily, very few of the things ordinary Chinese people eat or use come from the U.S. anyway.

#RMB purchasing power #China will inevitably be unified #Consumer confidence #Contemporary Chinese economy #Carrying forward the construction of a Beautiful China”

“Monday’s stock market will be a bloodbath,” another commenter wrote.

One Weibo blogger (@兰启昌) saw the recent developments as another sign of an ongoing trend of “de-globalization” (逆全球化).

But beyond global economics and geopolitics, many Chinese netizens — from Weibo to Xiaohongshu — seem more focused on how the new policies will affect everyday consumers.

Netizens have been actively discussing which goods will be hit hardest by the new tariffs. Based on 2023 trade data, here’s a breakdown of the top exports between China and the United States — and the sectors most likely to feel the impact.

🔷🇺🇸🇨🇳Top 10 Chinese Exports to the U.S.

1. Electronics and Machinery

Includes smartphones, laptops, tablets, integrated circuits, and image processing equipment.

2. Furniture, Home Goods & Toys

Such as video game consoles, lamps, and much more.

3. Textiles and Apparel

Garments, footwear, and accessories like sunglasses.

4. Metals and Related Products

Especially steel and steel-based items.

5. Plastic and Rubber Products

Widely used in packaging, manufacturing, and consumer goods.

6. Transportation Equipment

Electric vehicles, passenger cars, motorcycles, scooters, and drones.

7. Low-Value Commodities

Bulk items used in general trade and low-cost manufacturing.

8. Chemicals

Industrial chemicals and related materials.

9. Medical and Optical Instruments

Includes medical devices and precision instruments.

10. Paper Products

Ranging from office supplies to industrial paper goods.

🔹🇨🇳🇺🇸Top 10 U.S. Exports to China

1. High-Tech Machinery and Electronics

Especially integrated circuits, turbine engine components, and semiconductor manufacturing equipment.

2. Energy Products

Crude oil, liquefied propane and butane, natural gas, and coking coal.

3. Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals

Includes cosmetics, cleaning agents, and various medical drugs.

4. Soybeans

A key agricultural export widely used in food and animal feed in China.

5. Transportation Equipment

Such as automobiles and aircraft parts.

6. Medical and Optical Devices

Medical precision equipment, diagnostic tools, and lab instruments.

7. Plastic and Rubber Goods

Used in both consumer and industrial sectors.

8. Metal Products

Primarily iron and steel exports.

9. Wood and Pulp Products

Lumber, wood pulp, charcoal, and paper goods.

10. Meat

Including beef, pork, and poultry.

Those doing trade with the US, or otherwise involved in made-in-China products, like those working clothing and furniture factories, will inevitably be affected by the tariffs.

“Patriotism isn’t just a sentiment – it’s an action”

Much of the popular online conversation has focused on concrete examples of what kinds of things might get more expensive for Chinese consumers in their everyday lives.

Some bloggers noted that people might start to see price hikes in everyday groceries like dairy, meat, corn, and soybeans. With fewer soybeans coming in from the US, cooking oil prices may also rise.

China is the world’s largest consumer of soybeans, but because domestic production is relatively low, soybeans remain a key import.

Then there are popular American brands in the Chinese market that are expected to get pricier too — like beauty and health products, Starbucks coffee, or Häagen-Dazs ice cream.

Some also predicted a 30% to 40% increase in prices for iPhones and other Apple products.

Contrary to the earlier comment by the Xiaohongshu blogger, some netizens explain just how many American products are actually used by Chinese consumers, with many American companies operating in China — from McDonald’s and Coca-Cola, Walmart to Disney or Warner Brothers, Procter & Gamble to Colgate and Estée Lauder.

What’s noteworthy in these discussions, however, is a strong tendency to point to Chinese alternatives and encourage smart buying instead of following hypes (“理性替代,拒绝跟风”): No need to panic about soybeans — there are domestic alternatives, and China’s own soybean program is getting a boost. Who needs Starbucks when there’s Luckin Coffee? Why buy an iPhone when you can get a Huawei? Skip the Tesla, go for a BYD.

In these discussions, the ‘crisis’ is turned into an ‘opportunity’ for Chinese companies to focus even more on the Chinese market, and for Chinese consumers to, more than ever, actively embrace and celebrate local brands and made-in-China products.

One Chinese blogger (@O浅夏拾光O) wrote:

💬 “This moment is the time to reflect on our unity. If we can choose domestic alternatives, we should. For example, we can use rapeseed oil or peanut oil instead of imported soybean oil; we can buy cost-effective Chinese electronics instead of foreign brands. Support domestic products and respond to the nation’s call to expand domestic consumption.

We must have faith in our country. Only by uniting as one, young and old all together, the entire country working together, can we withstand all hazards. As Professor Ai Yuejin (艾跃进) once said, patriotism isn’t just a sentiment – it’s an action. As long as our core is stable and we are united in spirit, no hardship can defeat us.”

Despite the major happenings and the big words, some people just care about the small things: “As long as KFC and McDonald’s don’t raise their prices, it’s all fine by me.”

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Media

Revisiting China’s Most Viral Resignation Letter: “The World Is So Big, I Want to Go and See It”

The woman behind the famous resignation note, ‘I want to see the world,’ ended up traveling in China before going back home.

Published

3 weeks agoon

March 19, 2025

We include this content in the Weibo Watch newsletter. Subscribe to get it in your inbox 📩

“The world is so big, I want to go out and see it” (Shìjiè nàme dà, wǒ xiǎng qù kànkan “世界那么大,我想去看看”).

This ten-character sentence became part of China’s collective social media memory after a teacher’s resignation note went viral in 2015. Now, a decade later, the phrase has gone viral once again.

In April 2015, the phrase caused a huge buzz on China’s social media when the female teacher Gu Shaoqiang (顾少强) at Zhengzhou’s Henan Experimental High School resigned from her job.

Working as a psychology teacher for 11 years, she gave a class in which she made students write a letter to their future self. The exercise made her realize that she, too, wanted more from life. Despite having little savings, she submitted a simple resignation note that read: “The world is so big, I want to go out and see it.”

The resignation letter was approved, and she posted it to social media.

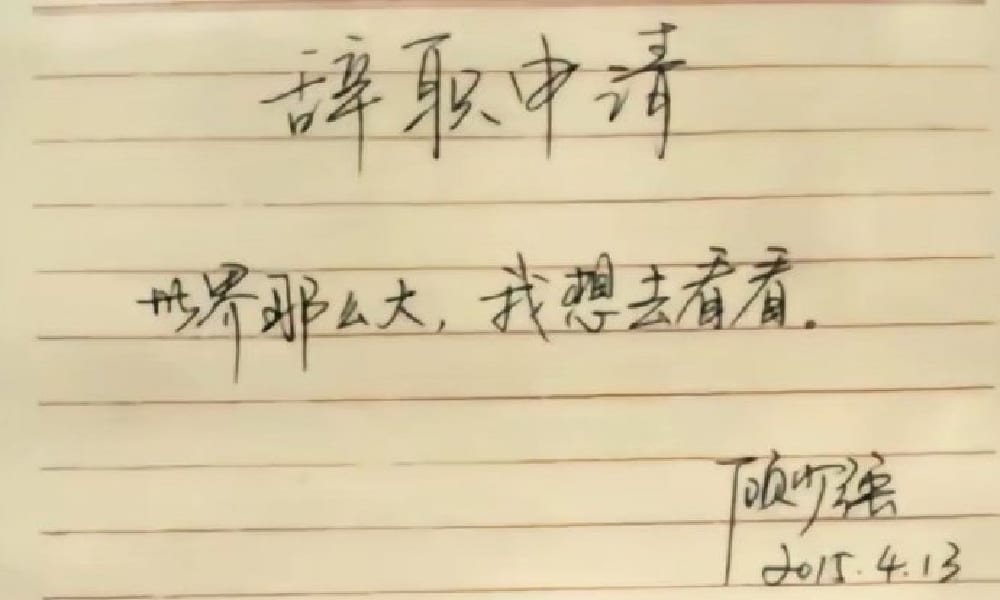

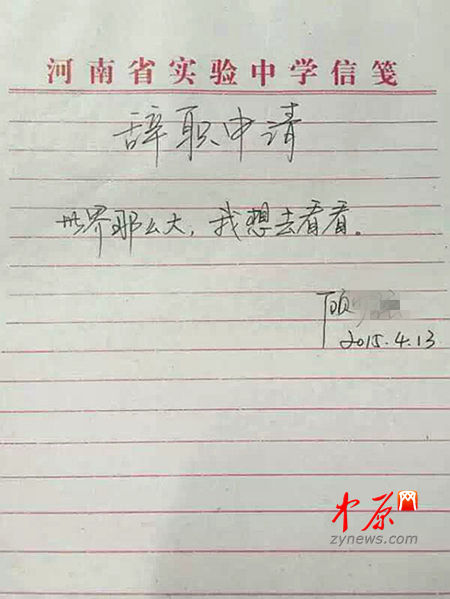

The resignation note that went viral, saying: “The world is so big, I want to go out and see it.”

The letter resonated with millions of Chinese who felt they also wanted to do something different with their life, like go and travel, see the world, and escape the pressures and routines of their daily life.

The phrase became so popular that it was adapted in all kinds of ways and manners, by meme creators, in books, by brands, and even by Xi Jinping, who said: “China’s market is so big, we welcome everyone to come and see it” (“中国市场这么大,欢迎大家都来看看”).

This week, Lěngshān Record (冷杉Record), the Wechat account under Chinese media outlet Phoenix Weekly (凤凰周刊), revisited the phrase and published a short documentary about Gu’s life after the resignation and the hype surrounding it.

An earlier news article about Gu’s life post-resignation already disclosed that Gu, despite receiving many sponsorship deals, never actually extensively traveled the world.

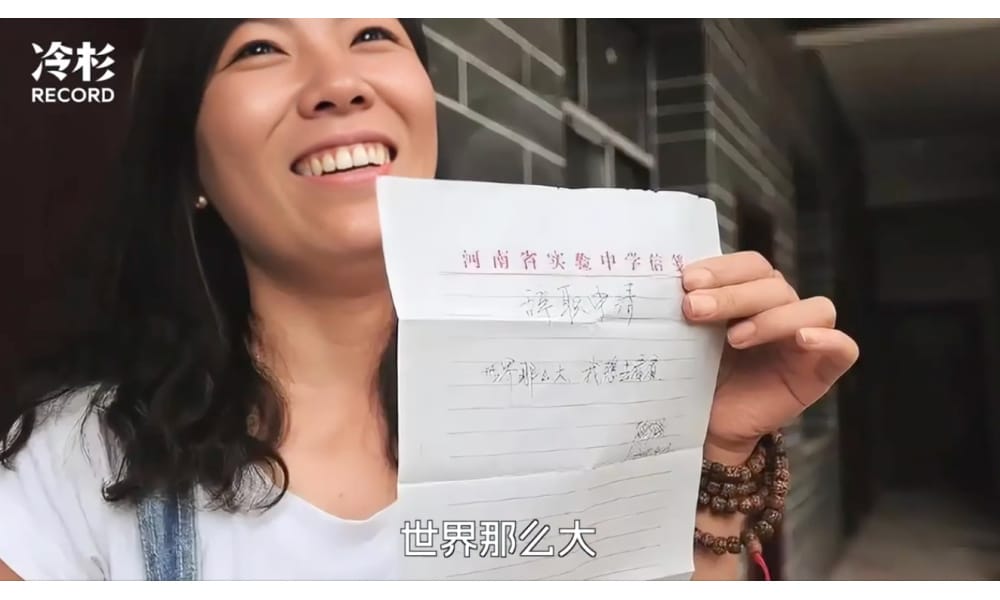

Gu and the viral resignation letter.

In the short documentary, Gu explains that she chose to “return home after seeing the world.” By this, she doesn’t mean traveling extensively abroad, but rather gaining life experience in a broader sense. While she did travel, it was within China, including in Tibet and Qinghai.

What truly changed was her life path. She left Zhengzhou and relocated to Chengdu to be near Yu Fu (于夫), a man she had met just weeks earlier by chance during a trip to Yunnan.

Six months after the resignation letter, she married him. Together, they ended up opening a hostel near Chengdu, married, and had a daughter.

Gu, now 45 years old, has been back in her hometown of Zhengzhou for the past years, caring for her aging mother and 9-year-old daughter. She is living separately from her husband, who manages their business in Chengdu. She also runs her own livestreaming and online parenting consultancy business.

Although the woman who wanted to “see the world” ended up back home, she has zero regrets about what she did, suggesting her courage to step out of the life she found limiting ultimately transformed her in a meaningful way.

On Chinese social media, the topic went trending on March 19. Most people cannot believe it’s already been ten years since the sentence went trending (“What? How could time fly like that?”).

Others, however, wonder about the hopes and dreams behind the original message—and how it all turned out.

“Seeing the world? She just escaped her old life, got married, and had a baby. How is that ‘seeing the world’?” one commenter wondered (@-NANA酱- ).

“The world is so big—what did she end up seeing?” others questioned. “She went from Zhengzhou to Chengdu.”

“Seeing the world takes money,” some pointed out.

But others came to her defense, saying that “seeing the world” also means stepping out of your comfort zone and exploring a different life. In the end, Gu certainly did just that.

“She was quite courageous,” another commenter wrote: “She gave up a stable job to go and see the world. Perhaps her life didn’t end up so rich, but the experiences she gained are priceless.”

The world is still big, though, and there’s plenty left for Gu Shaoqiang to see.

Read what we wrote about this in 2015: In The Digital Age, ‘Handwritten Weibo’ Have Become All The Rage

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

No Quiet Qingming: From High-Tech Tomb-Sweeping to IShowSpeed & the Seven China Streams

From Trade Crisis to Patriotic Push: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Tariffs

China Trending Week 14: Gucci Fake Lipstick, Xiaomi SU7 Crash, Yoon’s Impeachment

Strange Encounter During IShowSpeed’s Chengdu Livestream

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Beyond the Box Office: What’s Behind Ne Zha 2’s Success?

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

15 Years of Weibo: The Evolution of China’s Social Media Giant

Tuning Into the Year of the Snake

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

TikTok Refugees, Xiaohongshu, and the Letters from Li Hua

The ‘China-chic Girl’ Image and the Realities of China’s Competitive Food Delivery Market

“Black Myth: Wukong”: From Gaming Screens to the CMG Spring Festival Gala?

US-Russia Rapprochement and “Saint Zelensky”: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Shake-Up

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight11 months ago

China Insight11 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

-

China Arts & Entertainment11 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment11 months agoSinging Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Mary

October 1, 2022 at 2:00 am

Im an Iranian . The things you probably dont know about Iran is that the anti American protest that you mentioned is completely designed and directed by regime and all of those veil women and bearded men are somehow connected to the regime if not actors and actresses . They are Basij and their families . You called them “people “ they are not people at all . i dont know any Iranian that has ever said down to America or burn their flags when we were kids they made us do this in school every morning these are all fake and forced . Iranian people have nothing against the west . You mentioned that you read the comments and … Today in Iran regime admitted that they have hired 8000 people for commenting on social media to their fake news and in advance scenarios . We Iranians got used to this method