China Arts & Entertainment

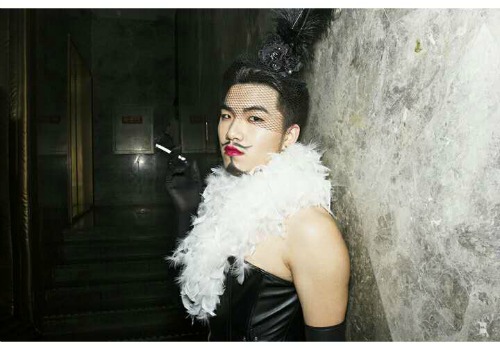

Beijing Close-Up: Photographer Tom Selmon Crosses the Borders of Gender in China

Tom Selmon, Beijing-based photographer from London, likes to capture a lesser-known side of China’s capital. Going off the beaten path, Selmon does backstage, fashion and street photography. His photos show a new Chinese generation that celebrates gender-nonconformity.

Published

9 years agoon

No Tiananmen Square or Summer Palace – Tom Selmon, Beijing-based photographer from London, likes to capture a lesser-known side of China’s capital. Going off the beaten path, Selmon does backstage, fashion and street photography. His photos show a new Chinese generation that celebrates gender-nonconformity.

This interview was conducted and condensed by Manya Koetse in Beijing.

LOVING THE CAMERA

“My work is a display of everything I love in the world.”

“I’ve always known I wanted to be behind the lens. I studied Film Studies in London and initially thought I would be a filmmaker. But I soon discovered I was not looking for long storyboards, I just wanted to shoot. So I started doing photography, and my teachers liked my work. I took a course in Fashion Photography and then decided that was what I was going to do. I love fashion, I love photography: I’d be a fashion photographer.”

“My work is a display of everything I love in the world. That includes people, faces, naked men, and drag. I’ve been interested in drag since I was 16. I probably was into it earlier than I realized: I already wore girl’s clothes at the age of two.”

“Besides my editorial work, I also shot the drag scene in London. I was photographing, doing another job on the side, and experimenting with shooting different things. I am gay and the [tooltip text=”Stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender.”]LGBT[/tooltip] scene is something I relate to. In my work, I hope to get across that I am doing it not to make a point – because actually it shouldn’t be a point. In many other photographer’s work, I feel drags or transgenders are often made to be look ugly. I just like unique faces and the shapes of bodies, and want to bring out the beauty in people.”

NEW TERRITORIES

“I wanted to go some place that would open my eyes.”

“When I was in London, I felt like I needed to push myself further and decided something needed to change. Someone I knew was living in Beijing, and I decided to take the jump and come here. I initially had no specific interest in China, I just wanted to go somewhere that was very different from London, some place that would open my eyes. I can say that now, looking back, because at the time I had no clue. I actually came for none of the reasons I thought I was coming for.”

“It was not easy in the beginning. I felt like Beijing was like a dream, and I was zoned out. The language barrier was a problem too: if I got into a taxi, all I could do was point at my address on a piece of paper. One of my first nights here my taxi driver ended up at taking me to the airport instead of my own home due to a miscommunication.”

“After some time I came into the right flow of meeting new people, finding a teaching job for steady income, and going out into the streets. It was only then that I really started to appreciate the city.”

SHOOTING BEIJING LIFE

“People here just stand around and have no idea how great they look.”

“There is this ‘flow’ in Beijing that I love. Once you’re in the flow of the city, it becomes easy to meet new people, to open doors and to start new projects.”

“I naturally got into Beijing street photography, because I just find so much life here. There is always something going on, from the early morning till late at night. I find it easier now to step up to people and ask if I can take their photo. It often turns into something really lovely. There is so much expression in people’s faces, and also some sort of honesty. Many people here just stand around and seem to have no idea how great they look. Beijing’s fashion is sometimes ridiculed, but many outfits are actually amazing, and people put a lot of energy into them. Those shots of the people combined with the urban environment give a very cool composition.”

“I am not very interested in shooting the cigarette seller down the street. I want to capture what is going on right now with the new generation. It’s iconic because it represents what is going on in 2016. I need to be in China longer to understand it, but there is some sort of new sexual revolution going on. Issues of gender and sexuality seem to be really playing a big role for this generation.”

CROSSING THE BORDERS OF GENDER IN CHINA

“I get a sense of pride and vulnerability in someone’s face here that I won’t get in London.”

“Continuing here what I did in London, I wanted to dive into the Beijing LGBT and drag scene. The ‘umbrella’ is LGBT, but I am also interested in shooting ballet dancers or other performers. I love those worlds that involve fluid gender identities, where people are giving beauty, elegance and movement.”

“I went to a rooftop screening of [tooltip text=”Fan Popo is a Beijing gay film maker, writer and activist.”]Fan Popo[/tooltip]’s documentary about the mothers of gay children in China in late Summer (2015), and that was my first entry into Beijing’s LGBT scene. I’m slowly getting to know it now, and I found that there is quite a tight community consisting of Chinese and foreign people. They organize many activities, and in that sense, it is different from London. People from the LGBT scene everywhere, also in London, still have to fight for equality. It is not like people in Beijing are fighting for something different, but they just have to fight harder.”

“The gays here have a different view on what it is to be gay. It also has to do with how people identify with being gay. Here, many homosexuals find it important to identify themselves as ‘feminine’ or ‘masculine’. It sometimes makes me think of what London used to be like ten years ago. There is a strong sense of gay pride.”

“There is this first generation here of both heterosexuals and gays now who are more open about sex. For me as a photographer, this new generation gives a myriad of people and scenes to shoot. I get a sense of pride and vulnerability in someone’s face here that I won’t get in London. There is a delicateness and femininity, which I find beautiful.”

“It has not been hard to find people willing to be photographed here. I always manage to get what I want from people. I just ask, and they say yes all the time. I also find that they are a bit more open to getting naked for a photo here. My recent work includes a photo series shot in a gay spa in downtown Beijing, individual portraits of people I have met on the streets, backstage series at contemporary dance shows and Chinese opera, and a project on the nouveau riche in one of Beijing’s super clubs. Maybe people are so willing to say yes because they are being shot in a way they have never been shot before.”

PHOTOS TO COME

”I’ve never understood why nudity is more censored than violence.”

“I am not sure what I am anymore. Am I a street photographer? A fashion photographer? An LGBT photographer? A nude photographer? Maybe I’m a bit of everything. My work is not about gays or transgenders, it is about people. My photos are not political; they are esthetical. I just love people and their bodies. It is all about faces, and how light reflects on the naked skin. Nudity makes people different. It is beautiful – I’ve never understood why nudity is more censored than violence.”

“I do hope to make an impact with my photos. In the end, I just want people to see my work. I do it because I really enjoy it.”

“I am not done yet in China, and I know that new opportunities will open up for me. I still have a lot to learn and to be exposed to here. I find it all very exciting. In London I always knew what was happening, and here I just never knew what is going to happen next. I don’t know where I’ll be one year from now. I am going to stay in China for another year, as I feel I have only just started to skim the surface.”

Photo on Tom Selmon’s Instagram. Tom Selmon on the left.

Photo on Tom Selmon’s Instagram. Tom Selmon on the left.

Tom Selmon’s website: www.tomselmon.com

Tom Selmon’s Instagram: follow

– By Manya Koetse

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

All images by Tom Selmon, do not reproduce without photographer’s permission.

©2016 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China ACG Culture

“Black Myth: Wukong”: From Gaming Screens to the CMG Spring Festival Gala?

Published

3 days agoon

January 21, 2025

FROM THE WEIBO WATCH PREMIUM NEWSLETTER

Is Chinese game sensation ‘Black Myth Wukong’ making a jump from gaming screens to the CMG Spring Festival Gala? There’s already some online excitement over a potential performance at the biggest liveshow of the year.

The countdown to the most-watched show of the year has begun. On January 29, the Year of the Snake will be celebrated across China, and as always, the CMG Spring Festival Gala, broadcast on CCTV1, will air on the night leading up to midnight on January 28.

Rehearsals for the show began last week, sparking rumors and discussions about the must-watch performances this year. Soon, the hashtag “Black Myth: Wukong – From New Year’s Gala to Spring Festival Gala” (#黑神话悟空从跨晚到春晚#) became a topic of discussion on Weibo, following rumors that the Gala will feature a performance based on the hugely popular game Black Myth: Wukong.

Three weeks ago, a 16-minute-long Black Myth: Wukong performance already was a major highlight of Bilibili’s 2024 New Year’s Gala (B站跨年晚会). The show featured stunning visuals from the game, anime-inspired elements, special effects, spectacular stage design, and live song-and-dance performances. It was such a hit that many viewers said it brought them to tears. You can watch that show on YouTube here.

While it’s unlikely that the entire 16-minute performance will be included in the Spring Festival Gala (it’s a long 4-hour show but maintains a very fast pace), it seems highly possible that a highlight segment of the performance could make its way to the show.

Recently, Black Myth: Wukong was crowned 2024’s Game of the Year at the Steam Awards. The game is nothing short of a sensation. Officially released on August 20, 2024, it topped the international gaming platform Steam’s “Most Played” list within hours of its launch. Developed by Game Science, a studio founded by former Tencent employees, Black Myth: Wukong draws inspiration from the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West. This legendary tale of heroes and demons follows the supernatural monkey Sun Wukong as he accompanies the Tang Dynasty monk Xuanzang on a pilgrimage to India to retrieve Buddhist scriptures. The game, however, focuses on Sun Wukong’s story after this iconic journey.

The success of Black Myth: Wukong cannot be overstated—I’ve also not seen a Chinese video game be this hugely popular on social media over the past decade. Beyond being a blockbuster game it is now widely regarded as an impactful Chinese pop cultural export that showcases Chinese culture, history, and traditions. Its massive success has made anything associated with it go viral—for example, a merchandise collaboration with Luckin Coffee sold out instantly.

If Black Myth: Wukong does indeed become part of the Spring Festival Gala, it will likely be one of the most talked-about and celebrated segments of the show. If it does not come on, which we would be a shame, we can still see a Black Myth performance at the pre-recorded Fujian Spring Festival Gala, which will air on January 29.

Lastly, if you’re not into video games and not that interested in watching the show, I still highly recommend that you check out the game’s music. You can find it on Spotify (link to album). It will also give you a sense of the unique beauty of Black Myth: Wukong that you might appreciate—I certainly do.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Chinese Movies

Why Chinese Hit Movie “Her Story” is ‘Good Stuff’: Stirring Controversy and Celebrating Female Perspectives

China’s end-of-year movie hit, Her Story, is sparking debates and highlighting the rising influence of Chinese female directors.

Published

2 months agoon

December 7, 2024

The Chinese comedy-drama Her Story (好东西, literally “Good Stuff”), directed by Shao Yihui (邵艺辉), has been gaining attention and sparking discussions on Weibo since its late November release in mainland China.

The film features an all-star cast including Song Jia (宋佳), Zhong Chuxi (钟楚曦), Zeng Mumei (曾慕梅), Zhao Youting (赵又廷), and Zhang Yu (章宇). It tells a quirky yet heartfelt story about two women: Wang Tiemei (王铁梅), a self-reliant single mom juggling life and work, and Xiao Ye (小叶), a free-spirited young woman navigating her chaotic relationships.

Their friendship begins when Xiao Ye starts babysitting Tiemei’s nine-year-old daughter, Wang Moli (王茉莉). Xiao Ye introduces her drummer friend, Xiao Ma (小马), to teach Moli how to play the drums, but Xiao Ma’s presence stirs jealousy in Tiemei’s unemployed ex-husband, who schemes to regain his place in the family. Blending humor with poignant insights, the film explores themes of imperfect love, friendship, and the messy process of rebuilding lives.

(“Her Story” poster and the director Shao Yihui)

The film also addresses a range of hot societal issues through dialogues woven into everyday interactions, touching on topics like menstruation stigma, sexual consent, feminism, and how family dynamics can impact personal development.

In just eight days, Her Story surpassed 300 million RMB ($41 million) at the Chinese box office (#好东西票房破3亿#). Two days later, on December 2, it exceeded 400 million RMB (#好东西票房破4亿#), and on December 7 news came out that it had surpassed the 500 million RMB ($68.7 million) mark at the box office.

The film also achieved an impressive 9.1/10 rating on Douban, a Chinese platform similar to IMDb, making it the highest-rated domestic film on Douban in 2024.

(“Her Story” on Douban)

Notably, 65.4% of voters awarded it five stars, while only 0.5% gave it one star.

Conflicting Views: From Feminist Film to Chick Flick

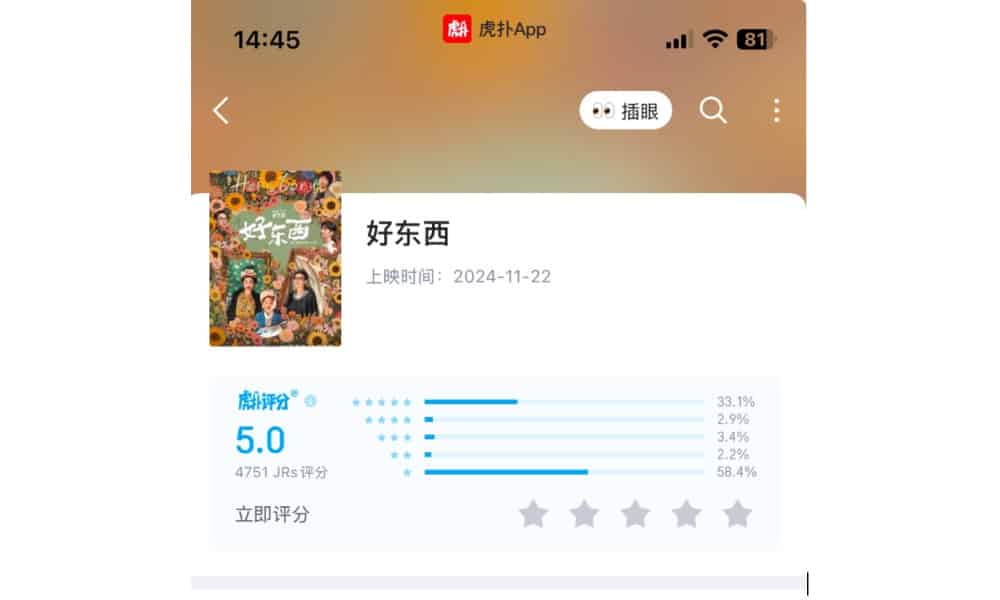

Despite its huge success, it is almost unavoidable for a movie this big to come without controversy. The film sparked debate on Hupu (虎扑), a platform focused on sports and men’s lifestyle, where it received a lower score of 5/10. While 33.1% of users gave it five stars, 58.4% rated it one star, reflecting divided opinions.

(“Her Story” on Hupu)

Much of the criticism comes from male viewers who feel the film undermines men by portraying them in non-traditional ways and omitting proper names for male characters, such as referring to the ex-husband only as “the ex-husband” (前夫). On the other hand, many female viewers resonate with the film’s female-centered perspective, with one scene blending household sounds and Xiao Ye’s recordings praised as a standout cinematic moment of 2024.

Interestingly, not all women appreciated the film either. A Weibo user, identified as a female scriptwriter for two Chinese TV dramas, emphasized that most of the producers of the film are male. She accused the director of hypocrisy, claiming Shao accepts money and resources from privileged men to create films that encourage female audiences to look down on average men.

She wrote, “I hope that everyone who believes in the ‘ghg’ [girl help girl] myth and supports female idols will also congratulate the male producers who will earn a lot of money from the film.”

Zhou Liming (周黎明), one of China’s most influential film critics, noted two extreme perspectives in film reviews. Some critics label the film as a “boxer film” (拳师电影) or an “extreme feminist film.”

However, the film itself suggests otherwise, as reflected in Moli’s line, “I don’t want to box,” when her father tries to convince her to take up boxing. Some audiences interpreted the line as rejecting extreme feminist messages.

In China, the term “boxer” (拳师) is used to critique certain feminists. The second character in the word for feminists (“权” [quán] in 女权主义者) is pronounced the same as the first character in “boxer” (“拳” [quán] in 拳师). This term often mocks behaviors seen as overly aggressive or lacking nuance in feminist discourse, such as avoiding dialogue or oversimplifying social issues.

Some also dismissed the film as a “chick flick,” a casual term for romantic comedies, which Zhou argued unfairly minimizes its significance. He likened the film to Woody Allen’s Annie Hall, suggesting that, much like Allen’s work, Her Story transcends gender differences and reflects the cultural zeitgeist of its time.

Despite the controversy, the film has been praised by notable figures like actor Zhang Ruoyun (张若昀), who called it “super good, super awesome, and super cute” (“超级好、超级牛、超级可爱的东西”). Zhang described the movie as tackling absurd yet realistic issues from a female perspective with humor and depth.

The Increasing Influence of Female Directors in China

At the end of Her Story, Tiemei’s daughter, Moli, nervously prepares for her first drum performance. Despite her hesitation, she gathers her courage and steps on stage. This moment reminded some viewers of a similar scene in another female-directed film this year, YOLO (麻辣滚烫), where the protagonist gears up for a boxing match.

YOLO is a 2024 comedy-drama directed by Jia Ling (贾玲), starring Jia Ling and Lei Jiayin (雷佳音). A comedic adaptation of the Japanese film 100 Yen Love (2014), it tells the story of Du Leying (杜乐莹), a woman facing personal struggles who turns to boxing after meeting coach Hao Kun (昊坤). Through her journey, she finds a new direction in life after their breakup. Grossing USD 496 million worldwide, YOLO became the highest-grossing Chinese film of 2024.

These parallels between Her Story and YOLO highlight a broader trend: the growing prominence of female directors in Chinese cinema. Beyond the discussions of plot and central themes, Her Story reflects the increasing success and influence of women filmmakers in the industry.

In 2024, female directors have made a notable impact on Chinese cinema, with their films achieving both critical acclaim and box office success. Their works also spark conversations about the need for more diverse perspectives in the industry.

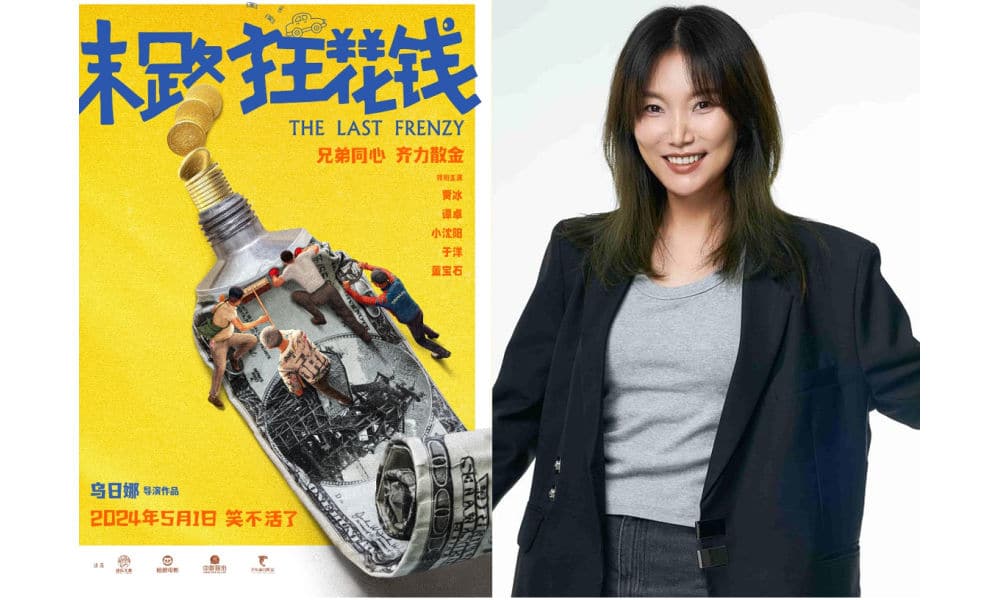

(“The Last Frenzy” poster and the director Wu Rina)

The Last Frenzy (末路狂花钱), directed by Wu Rina (乌日娜), premiered on May 1. This comedy follows Jia Youwei (贾有为), a man diagnosed with a terminal illness, who decides to sell his assets and live fully with his friends. Despite mixed reviews and a Douban score of 5.9, the film grossed over 700 million RMB ($96 million) by May 31, becoming a major box office hit.

(“Stand By Me” poster and the director Yin Ruoxin)

Stand By Me (野孩子, literally “Wild Kids”), directed by Yin Ruoxin (殷若昕), premiered on September 13. Starring Wang Junkai (王俊凯), it tells the story of two neglected children, Ma Liang (马亮) and Xuan Xuan (轩轩), who form a makeshift family while facing life’s challenges. With a Douban rating of 6.7, the film grossed 241 million RMB by October 9.

(“Like A Rolling Stone” poster and the director Yin Lichuan)

Like A Rolling Stone (出走的决心, literally “The Determination to Leave”), directed by Yin Lichuan (尹丽川), premiered the same week as Stand By Me. Inspired by Su Min (苏敏), a 50-year-old woman who embarked on a solo road trip, the film explores themes of self-discovery and the struggles of neglected women. Featuring Yong Mei (咏梅), the film earned praise for its authenticity, achieving a Douban score of 8.8 and grossing over 123 million RMB.

To the Wonder (我的阿勒泰, literally “My Altay”), a film-like TV drama directed by Teng Congcong (滕丛丛), adapts Li Juan’s (李娟) memoir. Starring Ma Yili (马伊琍), it tells the story of Li Wenxiu (李文秀), a young woman finding her place in her hometown of Altay after setbacks in the big city. Known for its poetic storytelling and portrayal of ethnic harmony, the series has a Douban score of 8.9 from over 300,000 ratings, ranking among the top dramas of 2024.

“An Era Where Women Are Being Seen”

The growing influence of female directors has sparked discussions about how women’s perspectives are challenging traditional storytelling.

Some Weibo users compared a scene from Her Story, where Tiemei scolds a man for urinating roadside, to a similar moments in YOLO. In YOLO, Hao Kun’s attempt to urinate roadside is humorously interrupted by car headlights. Such scenes highlight how female directors reinterpret everyday behaviors, inviting audiences to question societal norms.

Her Story has already been released in several countries, including the United States, Australia, Germany, and the United Kingdom, with more international releases to follow.

The success of Her Story, the conversations it inspires, and its contribution to highlighting female perspectives in film reflect the evolving dynamics of contemporary cinema and the strengthening of female voices in traditionally male-dominated industries.

On Weibo, many view this as a positive development. One commenter wrote:

“Her Story [好东西/”Good Stuff”] is truly ‘good stuff.’ (..) At the start of this year, I watched YOLO, and at the end of this year, I watched Her Story. Suddenly, I feel very grateful to live in this era—the era where women are gradually being ‘seen.’ Both films hold very special meaning for me. It feels like everything has come together perfectly. I hope to see more outstanding works from female directors in the future, and I look forward to an era where there’s no gender opposition, only mutual equality.”

By Wendy Huang

Follow @whatsonweibo

Edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

What’s on Weibo Chapters

Subscribe

“Black Myth: Wukong”: From Gaming Screens to the CMG Spring Festival Gala?

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

TikTok Refugees, Xiaohongshu, and the Letters from Li Hua

15 Years of Weibo: The Evolution of China’s Social Media Giant

Introducing What’s on Weibo Chapters

The Price of Writing Smut: Inside China’s Crackdown on Erotic Fiction

Controversial Wanghong Livestreamers Are Becoming a Weibo Staple in China

Weibo Watch: “Comrade Trump Returns to the Palace”

The ‘Cycling to Kaifeng’ Trend: How It Started, How It’s Going

Hu Xijin’s Comeback to Weibo

Our Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

The Viral Bao’an: How a Xiaoxitian Security Guard Became Famous Over a Pay Raise

Why Chinese Hit Movie “Her Story” is ‘Good Stuff’: Stirring Controversy and Celebrating Female Perspectives

Chiung Yao’s Suicide Farewell Letter: An English Translation

12-Year-Old Girl from Shandong Gets Infected with HPV: Viral Case Exposes Failures in Protecting Minors

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music10 months ago

China Music10 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Insight11 months ago

China Insight11 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Digital8 months ago

China Digital8 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI