Featured

Pressured to get Married: For the Country and For Society

Every year, China’s bachelors and bachelorettes are dreading the return to their hometowns, as parents and family members will inescapably ask them that one question: “Why are you not married yet?”

Published

10 years agoon

WHAT’S ON WEIBO ARCHIVE | PREMIUM CONTENT ARTICLE

A creative protest against social marriage pressure has reignited online discussions about the status quo of China’s unmarried adults. While some support the choice of Chinese younger adults to be in charge of their own happiness, others suggest they are too focused on personal fulfillment.

Chinese New Year and the pressure to get married: it has already become an ‘old’ topic. Every year, China’s bachelors and bachelorettes are dreading the return to their hometowns, as parents and family members will inescapably ask them that one question: “Why are you not married yet?”

This year, a group of Chinese young women protested in Shanghai against their parents pressuring them to marry, holding signs saying: “Mum, please do not force me to get married during New Year, I’m in charge of my own happiness.”

Protest in Shanghai against marriage pressure, February 4, 2015 (Qingdao News).

Protest in Shanghai against marriage pressure, February 4, 2015 (Qingdao News).

The women became a hot topic amongst netizens and authors, reigniting the online discussion about the status quo of China’s unmarried adults. “Coming back to your hometown saying you don’t want to be pressured into marriage is like going to the dog meat festival saying you don’t want to eat dog,” says writer Mao Li.

The Shengnü and Shengnan ‘problem’

The term ‘shengnü’ (剩女 ‘leftover woman’) has been a somewhat derogatory catch phrase in China’s media for years. It refers to women who are still single at the age of 27 or above; usually well-educated ladies who have difficulties in finding a partner that can live up to their expectations.

Their disadvantage in finding a partner relates to existing ideas in Chinese culture about the ‘ideal’ marriage age of women. A recent survey has pointed out that 50% of Chinese men already consider a women ‘left over’ when she is not married at the age of 25.

The male counterpart of the shengnü is the so-called ‘shengnan’ (剩男, ‘leftover man’). Chinese men face great difficulties in finding a bride, as Mainland China has been faced with an unbalanced male-female ratio since the 1980s. At the peak of disparity in 2004, more than 121 boys were born for every 100 girls. One explanation for this imbalance is the traditional preference for boys and sex-selective abortions since the one-child policy was introduced in 1978.

According to estimations, there currently are 20 million more men than women under the age of 30 (Luo & Sun 2014, 5; Chen 2011, 2).

The abundance of both single women and men in present-day China would suggest that there is hardly a problem: why don’t they just get married? Problematically, the majority of China’s unmarried women are twenty-somethings who live in urban areas and are at the ‘high end’ of the societal ladder (relatively high income and education), whereas the majority of the shengnan are based in rural areas and are at the ‘lower end’ (lower income/education).

Since Chinese women traditionally prefer to ‘marry up’ in terms of age, income and education, and the men usually ‘marry down’, the men and women find themselves at the wrong ends of the ladder (Ding & Xu 2015, 114).

China needs a babyboom

“Get married soon and have lots of babies,” says Huang Wenzheng, activist and one-child policy opponent (Qi 2014). China is currently facing a rapid decline in births. At the same time, the population is aging.

It is estimated that over 25% of Chinese people will be 65 years and older in 2050, leaving the burden of care to younger generations (BBC 2012). Getting Chinese bachelors and bachelorettes to marry and produce children has thus gone beyond the wish for a wedding banquet and cute grandchildren – it has become an important matter to society.

According to recent statistics, 80% of China’s bachelors and bachelorettes over the age of 24 experience pressure by their families to get married when they go home for the holiday period. The festival is now even nicknamed the “marriage pressure holiday” (催婚假期).

Parents looking for a suitable partner for their single sons and daughter (Xinhua).

Parents looking for a suitable partner for their single sons and daughter (Xinhua).

After Chinese New Year, there generally is a 40% increase in blind dates. These meetings are often arranged by the parents, who attend ‘blind date events’ for their single sons or daughters. Many parents gather in public parks over the weekend, carrying banners with the picture and details of their unmarried child in the hopes of finding a suitable marriage partner for them.

“Don’t oppose to marriage pressure if you’re a loser”

Well-known scholar Yang Zao (杨早) responds to this topic on Tencent’s Dajia (‘Everybody’, a media platform for authors), with an essay titled “Pressured to Get Married: For the Country, For Society” (为了国家,为了社会,逼你结婚). Yang is the third author to discuss the New Year’s marriage pressure and the Shanghai girls who want to take their love life into their own hands. The other two columns are by female writer Mao Li (毛利), who wrote an essay titled “Prove You’re Not a Loser Before Opposing Marriage Pressure” (想反逼婚,先证明你不是废物), and columnist Zhang Shi (张石), whose piece is called “China’s ‘Pressured-Married’ and Japan’s ‘Non-Married””(中国的“逼婚”和日本的“不婚”). Yang analyses the current debate on marriage, wondering if it is so controversial because society is pressuring it more or because unmarried adults are opposing it more.

Parents put more pressure on their children to get married, and children increasingly oppose it, says Mao Li. According to her, both sides make sense, but it is the children who have to explain their point-of-view; why would their parents understand them?

Those who were born in the 1980s and 1990s come from completely different times than their mothers and fathers, who suffered many hardships to get where they are today. Mao Li compares the way they raised their children to a farmer raising his crops: planting seeds, watering the fields and creating the right environment to grow. Now that the children are grown up and have left the family home, the logical step for them would be to get married – after all, their parents worked hard to build the right conditions for them to do so. They should not be surprised when their parents urge them to get settled.

“Coming back to your hometown saying you oppose to marriage pressure is like coming to the dog meat festival saying you oppose to eating dog,” Mao says: “You can’t expect people to comprehend it.” According to Mao, children can only oppose marriage pressure when they are completely independent. They cannot oppose marriage and still cling to their parents for financial support. “Prove you’re not a loser before opposing marriage pressure,” she says.

Writer Zhang Shi approaches the issue from another perspective; that of society. In Japan, fertility rates have sharply decreased. While society is ageing, the lack of young workers causes economic problems.

In order not to end up with the same problems as Japan, China has to get the marriages coming and birth rates going, argues Zhang. Parents who are forcing their children to get married are actually contributing to society, says Zhang: it is ‘warm advice’, not cold pressure. In an age of declining birthrates, urging people to have babies is a “social responsibility”.

“For the country, for society, for parents, can’t you let go a bit of ‘personal happiness’?”

The pressure to get married is ingrained in social ideology and China’s traditional family ethics, says Yang Zao. The problems that now emerge within society come from a clash between individualist and collectivist values.

Chinese society cannot be a perfect mix of both individualism and collectivism, according to Yang: “It is either one, and both will have downsides.” If China wants a liberal, individual-focused society, then its “evils” will have to be accepted too: some people will marry late, some will not marry at all, some will not have kids, others will go job-hopping, some people move from city to city and never settle down. Such a society will also generate low birth rates and an ageing society.

In a collective, family-focused society, the aging crisis and declining birth rates could be halted. Parents would not have to go to public parks to search for suitable partners for their unmarried kids. “For the country, for society, for parents, can’t you let go a bit of personal happiness’?”, says Yang. After all, isn’t marriage key to solving China’s present-day problems?

Since 1950, marriage officially is a ‘freedom of choice’ in Mainland China. Nevertheless, marriage in China still seems to involve more than two people: it is a get-together of two families with societal backing.

One Weibo user says: “The shengnü do not have an individual problem; they are a problem because society at large believes they have a problem – this is why it is a ‘problem’.”

No matter what the ‘nation’, ‘society’, or parents think, the protesting Shanghai girls are positive about their future: it is in their hands, and in their hands alone.

– by Manya Koetse

References

BBC. 2012. “Ageing China: Changes and Challenges.” BBC News, 19 September http://www.bbc.com/news/world-

Chen, Zhou. 2011. “The Embodiment of Transforming Gender and Class: Shengnü and Their Media Representations in Contemporary China.” Master’s thesis, University of Kansas.

Ding, Min and Jie Xu. 2015. The Chinese Way. Routledge: New York.

Luo, Wei, and Zhen Sun. 2014. “Are You the One? China’s TV Dating Shows and the Sheng Nü’s Predicament.” Feminist Media Studies, October: 1–18.

Mao Li 毛利. “想反逼婚,先证明你不是废物” [Prove You’re Not a Loser Before Opposing Marriage Pressure]. Dajia, 11 February http://dajia.qq.com/blog/466362096792665 [24.2.15].

Qi, 2014. “Baby Boom or Economy Bust.” The Wall Street Journal, 2 September http://blogs.wsj.com/chinarealtime/2014/09/02/baby-boom-or-economy-bust-stern-warnings-about-chinas-falling-fertility-rate/ [24.2.15].

Yang Zao 杨早. 2015. “为了国家,为了社会,逼你结婚” [Pressured to Get Married: For the Country, For Society]. Dajia, 17 February http://dajia.qq.com/blog/431261063359665 [24.2.15].

Zhang Shi 张石. 2015. “中国的“逼婚”和日本的“不婚” [China’s ‘Pressured-Married’ and Japan’s ‘Non-Married’]. Dajia, 16 February http://dajia.qq.com/blog/462372023502987 [24.2.15].

Image by Tencent Dajia, 2015.

©2014 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

You may like

China Military

“Li Jingjing Was Here”: Chinese Netizens React to Rumors of “Chinese Soldiers” in Russia

“We should tell Li Jingjing to come home. Risking your life on the battlefield for Russia is not worth it!”

Published

2 days agoon

March 3, 2025

A video that has been making its rounds on X and Bluesky on March 2/3 has fueled speculation about whether Chinese nationals might be serving in Russian military units.

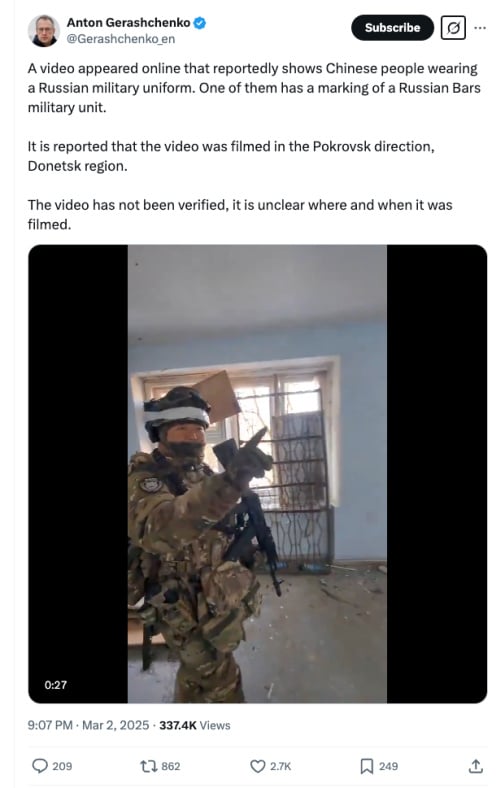

Ukrainian commentator and former adviser to Ukraine’s Minister of Internal Affairs, Anton Gerashchenko, posted:

“A video appeared online that reportedly shows Chinese people wearing a Russian military uniform. One of them has a marking of a Russian Bars military unit. It is reported that the video was filmed in the Pokrovsk direction, Donetsk region. The video has not been verified, it is unclear where and when it was filmed.”

The footage shows two soldiers inside an abandoned building, with one of them writing in Chinese on the wall: “Li Jingjing was here” (“李晶晶到此一游”). The two also exchange a few words in Chinese, saying things like, “Ah, I wrote it wrong again.” One of them wears an armlet belonging to BARS (Combat Army Reserve of Russia) military unit.

On one side of the wall, the words “-Wèi Precision Installation” (..卫精工安装) are written.

Other X accounts, including the influential Chinese account @whyyoutouzhele, pro-Ukrainian Oriannalyla (@Lyla_lilas) and UAVoyager (@NAFOvoyager) also posted the video on March 2nd, alleging that the footage came from Selydove, Donetsk region, and shows Chinese soldiers as part of Russian forces in the Pokrovsky direction. The source of the video posted by the second X user is the Telegram channel “Donbas Operative.”

Meanwhile, on Weibo, the same video is also being discussed by various commentators and netizens.

Digital & tech blogger ‘Ma Shang Tan” (@马上谈), who has over 480,000 followers on the platform, dismissed the rumors as fake, writing:

“Li Jingjing was here! Ukrainian media have published a condemning the presence of Chinese soldiers in the Russian camo… but that’s really too one-sided. Just because they write Chinese doesn’t mean they represent the Chinese people. First, Russia is offering high pay to recruit mercenaries, attracting people from all over the world who are willing to risk their lives for money. Second, as Russia continues to suffer losses, they’ve turned their focus to ethnic groups from the Far East, recruiting quite a few people in the army, many of whom will know Chinese characters.

Anyway, who even is this Li Jingjing? 😂😂😂😂”

Some commenters note that these soldiers “clearly aren’t Chinese,” some pointing to their appearance, others to how the characters were written—suggesting the characters are written “too wide.”

“This kindergarten level of characters is supposed to be written by a Chinese person?” another person wondered.

“I can immediately tell these are characters written by Koreans,” one Weibo user commented.

Since October 2024, South Korean intelligence has been reporting the presence of North Korean troops in Russia. However, their participation was never officially confirmed by Moscow or Pyongyang.

Another Weibo blogger, the military blogger “Earth Lens A” (@地球镜头A), with more than 950,000 followers, suggested that the “soldiers” could be Chinese, but that they are most likely people dressing up:

““Li Jingjing was here?” Ukrainian social media are framing it as if Chinese people are fighting in the war in the Russian forces. After fabricated claims of “North Koreans fighting in Kursk,” Ukrainian sources are now loudly claiming that Chinese troops have appeared near Pokrovsk, based on a random short video without any source.:

““…Precision Installation”? [“..精工安装”: referring to characters written on the wall in the abandoned building] These people wearing Russian military uniforms and speaking Chinese are either military enthusiasts from China doing cosplay or they’re some vloggers who went to Russia “pretending to be in combat.” Can’t say much else. Speaking of which, they should [do more to] control those Douyin and Kuaishou creators who claim to be fighting on the front lines.”

There is a thriving “cosplay culture” on Chinese short video platforms, and military cosplay is a part of that. Among Chinese younger people, cosplay (‘costume play’) has become increasingly popular over the past years. Cosplay allows people to become something they are not—a superhero, a villain, a sex symbol, a soldier—sometimes Chinese, American, Japanese, or Russian.

Some commenters allege that this particular video was made by creators on the video platform Bilibili, although there is currently no proof of that.

“It’s just some military fans playing in a dilapidated building,” another person wrote.

Meanwhile, there seems to be growing fascination over who Li Jingjing actually is.

“We should urge Li Jingjing to come home!” one blogger wrote: “It’s not worth dying on the Russian battlefield.”

They jokingly added: “Li Jingjing, your mom is calling you home for dinner!”

The phrase is a reference to a famous moment in Chinese internet history when a comment appeared on a World of Warcraft forum saying that a boy named Jia Junpeng was being called home for dinner by his mom (read here).

For some netizens, the fact that this video and its virality are being taken seriously on Western platforms seems to be a source of entertainment: “This video of Chinese cosplayers has started circulating on Twitter (X). It’s hard not to laugh watching their serious analysis.”

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Memes & Viral

How Ne Zha 2’s Shen Gongbao Became Known as the Ultimate “Small-Town Swot”

Published

4 days agoon

March 1, 2025

PART OF THIS TEXT COMES FROM THE WEIBO WATCH PREMIUM NEWSLETTER

Over the past few weeks, the Chinese blockbuster Ne Zha 2 has been trending on Weibo every single day. The movie, loosely based on Chinese mythology and the Chinese canonical novel Investiture of the Gods (封神演义), has triggered all kinds of memes and discussions on Chinese social media (read more here and here).

One of the most beloved characters is the leopard demon Shen Gongbao (申公豹). While Shen Gongbao was a more typical villain in the first film, the narrative of Ne Zha 2 adds more nuance and complexity to his character. By exploring his struggles, the film makes him more relatable and sympathetic.

In the movie, Shen is portrayed as a sometimes sinister and tragic villain with humorous and likeable traits. He has a stutter, and a deep desire to earn recognition. Unlike many celestial figures in the film, Shen Gongbao was not born into privilege and never became immortal. As a demon who ascended to the divine court, he remains at the lower rungs of the hierarchy in Chinese mythology. He is a hardworking overachiever who perhaps turned into a villain due to being treated unfairly.

Many viewers resonate with him because, despite his diligence, he will never be like the gods and immortals around him. Many Chinese netizens suggest that Shen Gongbao represents the experience of many “small-town swots” (xiǎozhèn zuòtíjiā 小镇做题家) in China.

“Small-town swot” is a buzzword that has appeared on Chinese social media over the past few years. According to Baike, it first popped up on a Douban forum dedicated to discussing the struggles of students from China’s top universities. Although the term has been part of social media language since 2020, it has recently come back into the spotlight due to Shen Gongbao.

“Small-town swot” refers to students from rural areas and small towns in China who put in immense effort to secure a place at a top university and move to bigger cities. While they may excel academically, even ranking as top scorers, they often find they lack the same social advantages, connections, and networking opportunities as their urban peers.

The idea that they remain at a disadvantage despite working so hard leads to frustration and anxiety—it seems they will never truly escape their background. In a way, it reflects a deeper aspect of China’s rural-urban divide.

Some people on Weibo, like Chinese documentary director and blogger Bianren Guowei (@汴人郭威), try to translate Shen Gongbao’s legendary narrative to a modern Chinese immigrant situation, and imagine that in today’s China, he’d be the guy who trusts in his hard work and intelligence to get into a prestigious school, pass the TOEFL, obtain a green card, and then work in Silicon Valley or on Wall Street. Meanwhile, as a filial son and good brother, he’d save up his “celestial pills” (US dollars) to send home to his family.

Another popular blogger (@痴史) wrote:

“I just finished watching Ne Zha and my wife asked me, why do so many people sympathize with Shen Gongbao? I said, I’ll give you an example to make you understand. Shen Gongbao spent years painstakingly accumulating just six immortal pills (xiāndān 仙丹), while the celestial beings could have 9,000 in their hand just like that.

It’s like saving up money from scatch for years just to buy a gold bracelet, only to realize that the trash bins of the rich people are made of gold, and even the wires in their homes are made of gold. It’s like working tirelessly for years to save up 60,000 yuan ($8230), while someone else can effortlessly pull out 90 million ($12.3 million).In the Heavenly Palace, a single meal costs more than an ordinary person’s lifetime earnings.

Shen Gongbao seems to be his father’s pride, he’s a role model to his little brother, and he’s the hope of his entire village. Yet, despite all his diligence and effort, in the celestial realm, he’s nothing more than a marginal figure. Shen Gongbao is not a villain, he is just the epitome of all of us ordinary people. It is because he represents the state of most of us normal people, that he receives so much empathy.”

In the end, in the eyes of many, Shen Gongbao is the ultimate small-town swot. As a result, he has temporarily become China’s most beloved villain.

By Manya Koetse, with contributions by Wendy Huang

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

What’s on Weibo Chapters

Subscribe

“Li Jingjing Was Here”: Chinese Netizens React to Rumors of “Chinese Soldiers” in Russia

How Ne Zha 2’s Shen Gongbao Became Known as the Ultimate “Small-Town Swot”

Beyond the Box Office: What’s Behind Ne Zha 2’s Success?

Ne Zha 2: Making Donghua Great Again

The Unstoppable Success of Ne Zha 2: Breaking Global Records and Sparking Debate on Chinese Social Media

Our Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Why Chinese Hit Movie “Her Story” is ‘Good Stuff’: Stirring Controversy and Celebrating Female Perspectives

Chiung Yao’s Suicide Farewell Letter: An English Translation

Breaking the Taboo: China’s Sanitary Pad Controversy Sparks Demand for Change

12-Year-Old Girl from Shandong Gets Infected with HPV: Viral Case Exposes Failures in Protecting Minors

Weibo Watch: Christmas in China Is Everywhere and Nowhere

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

Weibo Watch: China’s Online Feminism Is Everywhere

Story of Chinese Female MA Graduate Going Missing for 13 Years Sparks Online Storm

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight10 months ago

China Insight10 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music11 months ago

China Music11 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Insight12 months ago

China Insight12 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Digital9 months ago

China Digital9 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI