China Music

Rock ‘n’ Troll Chaos: The Controversy Surrounding Thefts at China’s Central Midi Festival

A theft scandal rocked China’s Midi Festival, which took place in Nanyang this week. Midi, however, blames online trolls for hyping the case.

Published

1 year agoon

What was supposed to be celebration of music, mud, and Midi freedom turned into a controversy that captured widespread attention on Chinese social media this week, as reports of looting surfaced online. As online discussions continue, people do not agree on who is to blame for the incident and the widespread attention for it.

The city of Nanyang in Henan has been all the talk on Chinese social media over the past few days due to large amounts of personal belongings getting stolen during the Central Midi Festival (中原迷笛音乐节).

The Midi Festival, founded by the Beijing Midi School of Music, is among China’s largest and most influential rock music festivals. Midi has been around for some thirty years, with variations in themes and taking place in different locations.

The most recent edition was held in Nanyang from September 29 to October 2nd. It drew approximately 150,000 visitors who flocked to Henan to have a good time, enjoy the music, dance in the mud, and stay at the camp site throughout the multi-day festival.

The local government had hoped that hosting the festival would help promote the city and make it more popular among young people. To create a positive impression, the entire city, including a remarkable 40,000 volunteers, local authorities, hotels, and transportation companies, dedicated their efforts to ensure the success of the Midi Festival. The mayor even personally welcomed festival-goers at the train station.

Free-for-all Festival

However, it seems that some locals had different intentions. They watched the festivities from behind the fences, and then started coming in and entering the camp sites. When they found unattended tents, as the owners were enjoying the music, they started stealing items from inside.

What began as isolated incidents soon escalated. More people joined in, more items were stolen, and the thieves grew bolder, sometimes even stealing from tents while their owners were present and trying to stop them.

There’s a video circulating showing an older lady rummaging through a festivalgoer’s tent while he filmed the scene. The lady casually stated, “I’ll take your camp light, dear,” and informed him of her theft.

Even sponsors and official vendors at the festival site fell victim to theft, as people entered their areas and stole their products and merchandise to resell later. There were reports of chairs and cables being stolen – essential items for a smooth-running festival.

Although security guards and police did intervene when the looting began, they allegedly just sent the thieves away at first without apprehending them. Some festivalgoers claimed to have lost personal items valued at over 10,000 RMB ($1,388).

By now, as the incident has gained national attention via social media, the case is being thorougly researched. The local police have received a total of 73 reports and they have confirmed 65 cases of theft. Some of the thieves have been arrested, and some of the stolen items have been recovered.

It Started with a Rumor

How could the festival looting get so out of control? According to local authorities in Nanyang, the incident began when a short video platform user known as “Wuyu” (无语) posted a video on October 2nd, falsely claiming that all the tents at the festival were available for taking as the event had ended and the premises needed to be cleared.

This rumor soon widely circulated, and prompted nearby villagers to come to the site to see what they could get.

The person behind the “Wuyu” account, identified as Chen Feng (陈峰), has since been identified and was taken into custody by the police.

On October 5, the Midi Festival released a statement on Weibo, reassuring the public that the festival and the local government are working together to try their best and recover all stolen items.

Statement by Midi.

Midi also lashed out against online ‘trolls’ who were hyping up the situation at Midi to smear the festival and the city’s reputation. The festival condemned both the small group of thieves and the larger group of online trolls.

Provincial Prejudice

The controversy has generated a lot of anger, not just among visitors and the festival organization staff, but also among local Nanyang authorities who had invested considerable effort into making the festival a success.

The incident has cast a shadow over Midi. In an online poll conducted by Fengmian Redian (@封面热点), a majority of respondents indicated that they would not want to attend the festival after this happened, expressing their disappointment over the looting.

The controversy also reflects badly on Henan, where people already face provincial prejudice. Henan is often characterized as a poor and unrefined province, associated with phone scammers or people who would even steal manhole covers to sell them for scrap metal, causing dangerous situations.

The Midi Festival controversy has perpetuated these stereotypes about the people of Henan, much to the dismay of local residents who have been actively working to challenge and dispel public biases against the province.

Rock ‘n’ Roll Chaos

While many Weibo users come to Nanyang’s defense, there are also those who stress that the local authorities should have taken more steps to improve security around the festival site.

Image by Midi, reposted by @后沙月光本尊 .

Others, however, do not agree. They argue that the Midi Festival, in Woodstock style, is about chaos, rock ‘n’ roll, and freedom. They think that the festival should not be overly controlled and that people should not blame the organization or local governments for not looking after their stuff.

Festival attendees and dedicated rock music enthusiasts argue that Midi, Nanyang, and the Chinese fans and musicians turned the festival into a great success.

Photos on Xiaohongshu capturing the atmosphere at Midi in Nanyang.

They suggest that the theft incident should not be attributed to them nor reflect badly on China’s thriving music scene; it was simply the result of immoral behavior from a few individuals who failed to grasp the spirit of the event.

Meanwhile, the entire incident has not just triggered anger; it has also become a source of banter and online jokes.

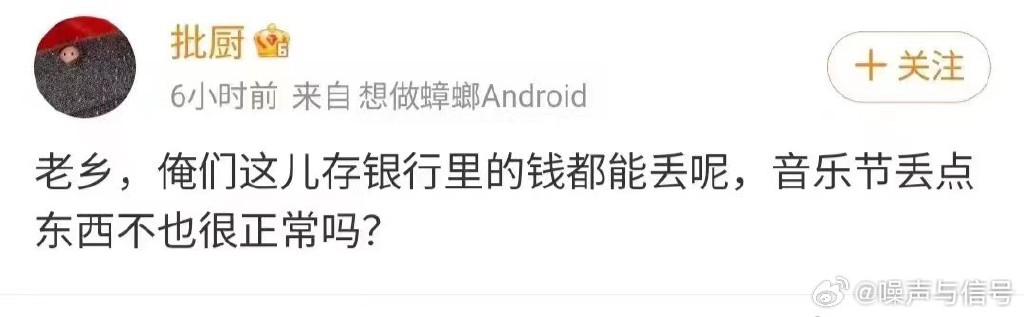

Some Henan natives are not exactly helping to promote their home province. One widely-shared comment referred to the Henan bank protests, stating: “If even the money we deposit in the bank can disappear, it’s no surprise that things can go missing at a music festival.”

By Manya Koetse and Miranda Barnes

with contributions by Miranda Barnes

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Arts & Entertainment

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

“I’m in Zibo eating barbecue, I really don’t feel like listening to Alicia Keys.” Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ has set off a new wave of national pride in China’s music and performers.

Published

8 months agoon

May 17, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

Besides memes and jokes, Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ has set off a new wave of national pride in China’s music and performers on Chinese social media.

In May, while the whole of Europe was gripped by the Eurovision Song Contest frenzy, Chinese audiences were eagerly anticipating the return of their own beloved singing competition, Singer 2024 (@湖南卫视歌手), formerly known as I Am a Singer (我是歌手).

The show, introduced from South Korea’s MBC Television and popular in China since 2013, only features professional singers who have already made a name for themselves.

Rather than watching unknown aspiring singers who are hoping to be discovered in many singing competitions, such as Sing! China, Singer 2024 gives audiences a show filled with professional and often stunning show performances by established names in the entertainment industry.

Since 2013, renowned singers from China and abroad have appeared on the show, including Chinese vocalist Tan Jing (谭晶), British pop singer Jessie J, and the late Hong Kong pop diva Coco Lee. However, no season managed to create as many waves as the 2024 season did, dominating all social media trending topics overnight.

So, what exactly happened?

COMPETING WITH FOREIGNERS

“The difference between the Grammys and the Strawberry Musical Festival”

In early May, the pre-show promotion of Singer 2024 was already buzzing on Chinese social media after a list of featured singers appeared on Weibo, including big names such as American singer-songwriter Bruno Mars, Korean-New Zealand singer Rosé from Blackpink, and Japanese diva LiSA.

Although Singer previously had many foreign singers on the show, this international celebrity lineup still caused a stir.

On the day of the first episode, only two foreign singers were announced to appear on the show: young Moroccan-Canadian singer Faouzia and the Grammy-nominated American singer-songwriter Chanté Moore. The other contestants were all Chinese singers who are already well-known among Chinese audiences. Because many people were unfamiliar with the two foreign singers, they joked that the winner of this season was already set in stone; surely it would be the famous Chinese singer Na Ying (那英), known for her beautiful voice.

However, that first episode surprised everyone as the two foreign singers, Faouzia and Chanté Moore, showed outstanding vocal skills. This not only startled many viewers but also made the Chinese contestants uneasy. Several experienced Chinese singers apparently were so unnerved after watching Faouzia and Chanté Moore’s performance that their voices trembled when singing.

Since the show was broadcast live – without post-production editing or autotune – audiences got to hear the actual vocal capabilities and see performers’ genuine reactions. It seemed undeniable that the foreign contestants did much better in terms of vocals and stage presence than the Chinese ones. Some online commenters even said that the gap between Chinese and foreign singers’ levels was like “the difference between the Grammys and the Strawberry Musical Festival” [a local Chinese music festival].

Chinese online influencer Yongkai (@陈咏开165) shared screenshots of Chanté Moore’s backstage reactions during the show. The American celebrity seemed puzzled when hearing the somewhat underwhelming performance by Chinese singer Yang Chenglin (楊丞琳), and she appeared much more positive when Na Ying sang.

This noteworthy scene, coupled with Chanté’s comments during an interview saying that she thought the Chinese production team had invited her on the show to be a judge, turned the entire show into a display of foreign singers outshining the Chinese contestants.

By the end of the first episode, Chanté Moore and Faouzia unsurprisingly ranked first and second, with Na Ying in third place.

After the show, some online commenters jokingly pointed out that Na Ying, being of Manchu descent like the rulers of China during the Qing Dynasty, showed some similarities to Empress Dowager Cixi’s defiance against Western colonizers in the way she “single-handedly took up against on foreigners” on the show.

They humorously turned Na Ying’s expressions into memes resembling Empress Dowager Cixi from an old Chinese TV show, with captions like “I want the foreigners dead” (“我要洋人死”).

Others suggested finding better Chinese singers for the show who could compete with Faouzia and Moore.

“SINGING WELL” CULTURALLY COLONIZED?

“I’m in Zibo eating BBQ, I really don’t want to listen to Alicia Keys.”

Initially, discussions about the show were light-hearted and humorous, until some netizens who couldn’t appreciate the jokes began to dampen the mood and made online discussions more serious.

Zou Xiaoying (@邹小樱), a music critic with nearly two million followers, posted on social media after the show, stating that he would have never voted for Chanté Moore or Faouzia. Not only did Zou question their vocal talent, he also wondered if the aesthetic of Chinese listeners had been influenced by Western music taste to such an extent that it has been “culturally colonized” (“文化殖民”). Meanwhile, he praised the members of Beijing rock band Second Hand Rose as “national heroes” (“民族英雄”).

He wrote:

If I had three votes for the first episode of “Singer 2024,” I’d vote for Second Hand Rose, Na Ying, and Silence Wang [note: Chinese singer-songwriter and record producer Wang Sushuang 汪苏泷]. The reason I wouldn’t vote for Chanté Moore or Faouzia is because — do they actually sing so well?

Has our definition of “singing well” perhaps been colonized? Just as our modern-day use of Chinese has little to do with our classical Chinese poems, with the foundation of modern Chinese actually being translations from the 20th century, is this also a form of ‘cultural colonization’?

You must think I’m talking nonsense again. But when I listen to Chanté Moore singing “If I Ain’t Got You,” I find it too boring. I know her singing is “good,” but this “good” has nothing to do with me. If, for Chinese listeners, Chanté Moore’s “good” is the standard, then is that what we in the music industry should be working towards? Isn’t that funny? When you open QQ Music or NetEase Cloud Music, and it recommends these songs to you every day, won’t you be convinced to practice again?

Of course, I know Chanté Moore is in good shape, very relaxed. Actually all of the Chinese singers tonight were very nervous. Yang Chenglin (杨丞琳) was nervous, Na Ying was also nervous. Even a seemingly carefree band like Second Hand Rose, if you listened to the introduction of their song, [you’ll find] they were so nervous that Yao Lan, supposedly “China’s No.1 Guitarist”, was so nervous that he hit the wrong note. It was not even a fast-paced solo (…), how nervous could he be? When everyone’s so tense, the confidence of Chanté Moore and Faouzia is indeed something that East Asia can’t match. In East-Asian [entertainment] circles, represented by China/Japan/Korea, our different cultural habits, upbringing, and ethnic characteristics have made it so that we don’t possess these kinds of singing abilities, even including our ways of emotional expression. I don’t know from which season it started with ‘Singer’ – and if it’s some kind of Catfish Effect (鲶鱼效应 ) – that they brought international singers with different cultural backgrounds into the competition. But this isn’t the Olympics, it’s not like Liu Xiang [刘翔, Chinese gold medal hurdler] is going to defeat opponents from the United States or Cuba. “I’m in Zibo eating barbecue, I really don’t feel like Alicia Keys.” (This line is not mine, I stole it from my WeChat friend).

Because of this, I find Second Hand Rose even more rare and precious. It’s just like I used to love asking: If you could only recommend one Chinese band to your foreign friends, which one would you recommend? Some say it’s New Pants (新裤子), some say it’s Omnipotent Youth Society, but my answer will always be Second Hand Rose. ‘The drama of Monkey King is a national treasure,’ its light will always shine. Facing the gunfire of Western powers, Second Hand Rose is standing on the frontline, they are our national heroes. Indeed, the band itself was nervous, (..), but when Chanté Moore goes off like a singing dolphin, we are fortunate to have Second Hand Rose at the frontline; the Chinese sons and daughters are building the Great Wall of Music of flesh and blood.

Because of this, I find Second Hand Rose even more rare and precious. It’s just like I used to love asking: If you could only recommend one Chinese band to your foreign friends, which one would you recommend? Some say it’s New Pants (新裤子), some say it’s Omnipotent Youth Society, but my answer will always be Second Hand Rose. ‘The drama of Monkey King is a national treasure,’ its light will always shine. Facing the gunfire of Western powers, Second Hand Rose is standing on the frontline, they are our national heroes. Indeed, the band itself was nervous, (..), but when Chanté Moore goes off like a singing dolphin, we are fortunate to have Second Hand Rose at the frontline; the Chinese sons and daughters are building the Great Wall of Music of flesh and blood.

Anyway, no matter if they’re strong or not, I would never vote for the foreigner.

The comment about ‘I’m in Zibo eating barbecue, I really don’t feel like [listening to] Alicia Keys’ refers to the craze surrounding China’s ‘BBQ town’ Zibo. In Zibo, Chinese visitors like to sing, drink beer, and enjoy food together; it’s a simple and modest way of appreciating life and music, which contrasts with slick and smooth American or foreign styles of performing and singing.

Whether Zou’s criticism was for attention or genuine sentiment, it shifted the focus of the discussion from music to patriotism.

CHINESE SINGERS WITH MILITARISTIC UNDERTONES

“I volunteer to join the battle”

Amidst all this, some netizens, easily swayed by nationalist sentiments, began to seek help from the “national team” (国家队) of singers — musicians employed by national-level arts troupes — to “bring glory to the nation” and teach the foreigners a lesson. Some even questioned the intentions of the Singer 2024 TV show in inviting foreign singers to participate.

On May 12th, renowned Chinese singer and philanthropist Han Hong (韩红) posted on Weibo, fueling a wave of sentiment and support. In her post, Han Hong declared, “I am Chinese singer Han Hong, and I volunteer to join the battle,” tagging the production team of the TV show. Her invitation to join the battle quickly went viral.

Han Hong meme: “Who called for me?”

Han Hong has significant influence in the Chinese music industry and society as a whole. Her usual serious demeanor and avoidance of internet pop culture made netizens unsure whether she was joking or serious. Nevertheless, regardless of her intentions, a group of well-known singers began to volunteer via Weibo, emphasizing their identity as “Chinese singers” and using phrases with strong militaristic undertones like “fighting for the country” and “answering the call.”

Although many enjoyed this new wave of national pride in Chinese music and performers, some netizens criticized the trend of transforming an entertainment show into a nationalistic competition.

Film critic He Xiaoqin (何小沁) stated, “It’s okay to take the Qing-Dynasty-fighting-foreigners comparison as a joke, but taking it too seriously in today’s context is absurd.”

Others expressed fatigue with how quickly topics on Chinese internet platforms escalate to patriotic sentiments. To bring the focus back to entertainment, they turned “I volunteer to join the battle” (#我请战#) into a new internet catchphrase.

In response, the production team of Singer 2024 released a statement on Weibo, thanking all the singers for their self-recommendations. They emphasized the show’s competitive structure but clarified that “winning” is just one part of a singer’s journey..but that the love of music goes beyond all in connecting people, no matter where they’re from.

By Ruixin Zhang, edited with further input by Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Memes & Viral

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

How a senior activity park in Chengdu was ‘Disneyfied’ and became a viral hotspot.

Published

10 months agoon

April 12, 2024

How did a common park turn into a buzzing hotspot? By mixing online trends with real-life fun, blending foreign styles with local charm, and adding a dash of humor and absurdity, Chengdu now boasts its very own ‘Chengdu Disney’. We explain the trend.

– By Manya Koetse, co-authored by Ruixin Zhang

Have you heard about Chengdu Disney yet? If not, it’s probably unlike anything you’d imagine. It’s not actually a Disney theme park opening up in Chengdu, but it’s one of the city’s most viral hotspots these days.

What is now known as ‘Chengdu Disney’ all over the Chinese internet is actually a small outdoor park in a residential area in Chengdu’s Yulin area, which also serves as the local senior fitness activity center.

Crowds of young people are coming to this area to take photos and videos, hang out, sing songs, cosplay, and be part of China’s internet culture in an offline setting.

Once Upon a Rap Talent Show

The roots of ‘Chengdu Disney’ can be traced back to the Chinese hip-hop talent show The Rap of China (中国新说唱), where a performer named Nuomi (诺米), also known as Lodmemo, was eliminated by Chinese rapper Boss Shady (谢帝 Xièdì), one of the judges on the show.

Nuomi felt upset about the elimination and a comment made by his idol mentor, who mistakenly referred to a song Nuomi made for his ‘grandma’ instead of his grandfather. His frustration led to a viral livestream where he expressed his anger towards his participation in The Rap of China and Boss Shady.

However, it wasn’t only his anger that caught attention; it was his exaggerated way of speaking and mannerisms. Nuomi, with his Sichuan accent, repeatedly inserted English phrases like “y’know what I’m saying” and gestured as if throwing punches.

His oversized silver chain, sagging pants, and urban streetwear only reinforce the idea that Nuomi is trying a bit too hard to emulate the fashion style of American rappers from the early 2000s, complete with swagger and street credibility.

Lodmemo emulates the style of American rappers in the early 2000s, and he has made it his brand.

Although people mocked him for his wannabe ‘gangsta’ style, Nuomi embraced the teasing and turned it into an opportunity for fame.

He decided to create a diss track titled Xiè Tiān Xièdì 谢天谢帝, “Thank Heaven, Thank Emperor,” a word joke on Boss Shady’s name, which sounds like “Shady” but literally means ‘Thank the Emperor’ in Chinese. A diss track is a hip hop or rap song intended to mock someone else, usually a fellow musician.

In the song, when Nuomi disses Boss Shady (谢帝 Xièdì), he raps in Sichuan accent: “Xièdì Xièdì wǒ yào diss nǐ [谢帝谢帝我要diss你].” The last two words, namely “diss nǐ” actually means “to diss you” but sounds exactly like the Chinese word for ‘Disney’: Díshìní (迪士尼). This was soon picked up by netizens, who found humor in the similarity; it sounded as if the ‘tough’ rapper Nuomi was singing about wanting to go to Disney.

Nuomi and his diss track, from the music video.

Nuomi filmed the music video for this diss track at a senior activity park in Chengdu’s Yulin subdistrict. The music video went viral in late March, and led to the park being nicknamed the ‘Chengdu Disney.’

The particular exercise machine on which Nuomi performed his rap quickly became an iconic landmark on Douyin, as everyone eagerly sought to visit, sit on the same see-saw-style exercise machine, and repeat the phrase, mimicking the viral video.

What began as a homonym led to people ‘Disneyfying’ the park itself, with crowds of visitors flocking to the park, some dressed in Disney-related costumes.

This further developed the concept of a Chengdu ‘Disney’ destination, turning the park playground into the happiest place in Yulin.

Chengdu: China’s Most Relaxed Hip Hop Hotspot

Chengdu holds a special place in China’s underground hip-hop scene, thanks to its vibrant music culture and the presence of many renowned Chinese hip-hop artists who incorporate the Sichuan dialect into their songs and raps.

This is one reason why this ‘Disney’ meme happened in Chengdu and not in any other Chinese city. But beyond its musical significance, the playful spirit of the meme also aligns with Chengdu’s reputation for being an incredibly laid-back city.

In recent years, the pursuit of a certain “relaxed feeling” (sōngchígǎn 松弛感) has gained popularity across the Chinese internet. Sōngchígǎn is a combination of the word for “relaxed,” “loose” or “lax” (松弛) and the word for “feeling” (感). Initially used to describe a particular female aesthetic, the term evolved to represent a lifestyle where individuals strive to maintain a relaxed demeanor, especially in the face of stressful situations.

🌟 Attention!

For 11 years, What’s on Weibo has remained a 100% independent blog, fueled by my passion to write about China’s digital culture and online trends. Over a year ago, we introduced a soft paywall to ensure the sustainability of this platform. I’m grateful to all our loyal readers who’ve subscribed since 2022. Your support has been invaluable. But we need more subscribers to continue our work. If you appreciate our content and want to support independent China reporting, please consider becoming a subscriber. Your support keeps What’s on Weibo going strong!

The concept gained traction online in mid-2022 when a Weibo user shared a story of a family remaining composed when their travel plans were unexpectedly disrupted due to passport issues. Their calm and collected response inspired the adoption of the “relaxed feeling” term (also read here).

Central to embodying this sense of relaxation is being unfazed by others’ opinions and avoiding unnecessary stress or haste out of fear of judgment.

Nowadays, Chinese cities aim to foster this sense of sōngchígǎn. Not too long ago, there were many hot topics suggesting that Chengdu is the most sōngchí 松弛, the most relaxed city in China.

This sentiment is reflected in the ‘Chengdu Disney’ trend, which both pokes fun at a certain hip-hop aesthetic deemed overly relaxed—like the guys who showed up with sagging pants—and embraces a carefree, childlike silliness that resonates with the city’s character and its people.

Mocking sagging pants at ‘Chengdu Disney.’

Despite the influx of visitors to the Chengdu Disney area, authorities have not yet significantly intervened. Community notices urging respect for nearby residents and the presence of police officers to maintain order indicate a relatively hands-off approach. For now, it seems most people are simply enjoying the relaxed atmosphere.

Being Part of the Meme

An important aspect that contributes to the appeal of Chengdu Disney is its nature as an online meme, allowing people to actively participate in it.

Scenes from Chengdu Disney, images via Weibo.

China has a very strong meme culture. Although there are all kinds of memes, from visual to verbal, many Chinese memes incorporate wordplay. In part, this has to do with the nature of Chinese language, as it offers various opportunities for puns, homophones, and linguistic creativity thanks to its tones and characters.

The use of homophones on Chinese social media is as old as Chinese social media itself. One of the most famous examples is the phrase ‘cǎo ní mǎ’ (草泥马), which literally means ‘grass mud horse’, but is pronounced in the same way as the vulgar “f*ck your mother” (which is written with three different characters).

In the case of the Chengdu Disney trend, it combines a verbal meme—stemming from the ‘diss nǐ’ / Díshìní homophone—and a visual meme, where people gather to pose for videos/photos in the same location, repeating the same phrase.

Moreover, the trend bridges the gap between the online and offline worlds, as people come together at the Chengdu playground, forming a tangible community through digital culture.

The fact that this is happening at a residential exercise park for the elderly adds to the humor: it’s a Chengdu take on what “urban” truly means. These colorful exercise machines are a common sight in Chinese parks nationwide and are actually very mundane. Transforming something so normal into something extraordinary is part of the meme.

A 3D-printed model version of the exercise equipment featured in Nuomi’s music video.

Lastly, the incorporation of the Disney element adds a touch of whimsy to the trend. By introducing characters like Snow White and Mickey Mouse, the trend blends American influences (hip-hop, Disney) with local Chengdu culture, creating a captivating and absurd backdrop for a viral phenomenon.

For some people, the pace in which these trends develop is just too quick. On Weibo, one popular tourism blogger (@吴必虎) wrote: “The viral hotspots are truly unpredictable these days. We’re still seeing buzz around the spicy hot pot in Gansu’s Tianshui, meanwhile, a small seesaw originally meant for the elderly in a residential community suddenly turns into “Chengdu Disneyland,” catching the cultural and tourism authorities of Sichuan and even Shanghai Disneyland off guard. Netizens are truly powerful, even making it difficult for me, as a professional cultural tourism researcher, to keep up with them.”

By Manya Koetse, co-authored by Ruixin Zhang

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

What’s on Weibo Chapters

Subscribe

“Black Myth: Wukong”: From Gaming Screens to the CMG Spring Festival Gala?

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

TikTok Refugees, Xiaohongshu, and the Letters from Li Hua

15 Years of Weibo: The Evolution of China’s Social Media Giant

Introducing What’s on Weibo Chapters

The Price of Writing Smut: Inside China’s Crackdown on Erotic Fiction

Controversial Wanghong Livestreamers Are Becoming a Weibo Staple in China

Weibo Watch: “Comrade Trump Returns to the Palace”

The ‘Cycling to Kaifeng’ Trend: How It Started, How It’s Going

Hu Xijin’s Comeback to Weibo

Our Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

The Viral Bao’an: How a Xiaoxitian Security Guard Became Famous Over a Pay Raise

Why Chinese Hit Movie “Her Story” is ‘Good Stuff’: Stirring Controversy and Celebrating Female Perspectives

Chiung Yao’s Suicide Farewell Letter: An English Translation

12-Year-Old Girl from Shandong Gets Infected with HPV: Viral Case Exposes Failures in Protecting Minors

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music10 months ago

China Music10 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Insight11 months ago

China Insight11 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Digital8 months ago

China Digital8 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI