Featured

Sex and the City – Women’s Sex in China (Liveblog)

Gender and sexuality specialist Dr. Pei about her book ‘Sex and the City’, a book for which she interviewed dozens of Chinese women about their sexuality. Pei explains her research, including masturbation and cyber sex.

Published

10 years agoon

Event: Lecture by Dr. Yuxin Pei on Masturbation/Sex in China

Date: May 21, 2015

Place: Leiden University, the Netherlands

Gender and sexuality specialist Yuxin Pei (裴谕新) talks about her book ‘Sex and the City: A Study of Shanghai Young Women born in the 1970s’, a book for which she interviewed dozens of women about their sexuality. Pei explains her research, including masturbation and cyber sex.

“In China, we don’t have sexual rights”

Today Yuxin Pei will talk about how to articulate women’s sex in China. “We don’t talk about sexual rights in China,” Dr. Pei says: “We don’t have them.” Pei explains how sex in China is considered part of a healthy lifestyle, together with sleeping and eating. When talking about sex, people therefore often refer to it as “sexual health” or “sexual needs”. Sex, especially for men, is seen as a natural part of life. Many women, however, say they do not need sex. Their excuse is that they are still a virgin, or that they are single, and that sex is therefore not a part of their lives. In Chinese traditional thought, still hugely influencing modern-day society, there are many misconceptions about women and sex. Women are not supposed to have sex when they are pregnant, for example, or when they are raising young kids and are tired. For couples who have been married for a long time, sex becomes taboo.

“One drop of semen equals ten drops of blood”

Masturbation is one of Pei’s research subject – a topic many Chinese people do not know much about. Pei therefore set up a “Masturbation Research Group” on Sina Weibo to get a discussion going on how people think about masturbation. “People asked me if it was an April Fools joke,” Pei says: “But it was very serious.” Pei wanted to research how people in China talk about masturbation. The video that was made for this, where people were asked if they had ever masturbated, received over 10 million views on Youku. Pei’s Weibo group now has over 30.000 followers, and due to the great interest in the subject, Pei organizes a monthly workshop on masturbation, where people from the age of 18 to 68 talk about sex.

Dr. Pei discovered many deeply ingrained misconceptions on masturbation. “Only men can do it”, “too much masturbation will give you small penis”, “one drop of semen equals ten drops of blood”, “I might not have normal sex again after masturbating”, or “women who masturbate are no good” – just a few examples of existing ideas on masturbation.

“Talking about masturbation opens the door to so many other topics,” Pei says: “Research on masturbation led us to conceptions about femininity, masculinity, gender, body image and even self-development.”

“What’s normal for men, is ‘dirty’ for women”

Masturbation was not Pei’s original focus of study. Pei Yuxin did her PhD at the University of Hong Kong over ten years ago, using Shanghai as her research field. “I talked to dozens of women from the 1970s about their sex lives,” she says: “and masturbation already came up during the second interview I did.” Pei was fascinated with the topic, as it brought up so many other issues concerning women and sex: while many sexual acts, including masturbation, are considered ‘healthy’ or ‘normal’ for men, they are considered ‘dirty’ for women. Oral sex is another example, Pei says, as women will give it to men, but will not accept it.

“Women really liked to talk about their experiences to me”, Pei says. She discovered that many women had experienced ‘cyber sex’ [having sex through camera online], as they felt ‘clean’ doing it – since they did not consider it “real sex”.

“Sexuality is empowering”

Pei Yuxin sees sex as female empowerment. Power and sex are intertwined in multiple ways, according to Pei.

In one chapter of her book she pays attention to the topic of women having affairs with foreign men, especially Western ones. “It’s not about the green card,” Pei says: “It’s cultural capital.” Many women told Dr. Pei that having a Western boyfriend is like having a private English teacher. It is a status symbol and improves their ability to compete on the Shanghai job market.

“Some women speak of their boyfriends as if they are picking restaurants,” Pei says: “Right now, it is said that a good boyfriend should have a car, a house and a dog.”

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, a group of female writers called “the Beauty Writers” (美女作家) became popular in China, one of them being Wei Hui, who wrote “Shanghai Baby”. These writers, who were young and beautiful, openly wrote about sex and relationships. Writing about their sexuality made them influential – the first powerful generation that put sexuality in Chinese literature. “What they did with their books then, is done online now,” Pei says: “Like famous blogger Muzi Mei (木子美), who published her sexual diary online.” The internet has made it possible for people to discuss sexual experiences and sexuality from behind their computer screens.

There is a long way to go for sexual rights in China: “There’s no act on marital rape or sexual harassment yet,” Pei says. The empowerment of women is one of the motors driving Pei’s research. Creating awareness on sexual issues and understanding the relation between sexuality and self-development will further the sexual liberation of Chinese women.

(This liveblog is now closed.)

Blogged by: Manya Koetse

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Arts & Entertainment

How K-pop Fans and the 13-Year-Old Daughter of Baidu VP Sparked a Debate on Online Privacy

What began as K-pop fan outrage targeting a snarky commenter quickly escalated into a Baidu-linked scandal and a broader conversation about data privacy on Chinese social media.

Published

4 days agoon

March 26, 2025By

Ruixin Zhang

For an ordinary person with just a few followers, a Weibo account can sometimes be like a refuge from real life—almost like a private space on a public platform—where, along with millions of others, they can express dissatisfaction about daily annoyances or vent frustration about personal life situations.

But over recent years, even the most ordinary social media users could become victims of “opening the box” (开盒 kāihé)—the Chinese internet term for doxxing, meaning the deliberate leaking of personal information to expose or harass someone online.

A K-pop Fan-Led Online Witch Hunt

On March 12, a Chinese social media account focusing on K-pop content, Yuanqi Taopu Xuanshou (@元气桃浦选手), posted about Jang Wonyoung, a popular member of the Korean girl group IVE. As the South Korean singer and model attended Paris Fashion Week and then flew back the same day, the account suggested she was on a “crazy schedule.”

In the comment section, one female Weibo user nicknamed “Charihe” replied:

💬 “It’s a 12-hour flight and it’s not like she’s flying the plane herself. Isn’t sleeping in business class considered resting? Who says she can’t rest? What are you actually talking about by calling this a ‘crazy schedule’..”

Although the comment may have come across as a bit snarky, it was generally lighthearted and harmless. Yet unexpectedly, it brought disaster upon her.

That very evening, the woman nicknamed Charihe was bombarded with direct messages filled with insults from fans of Jang Wonyoung and IVE.

Ironically, Charihe’s profile showed she was anything but a hater of the pop star—her Weibo page included multiple posts praising Wonyoung’s beauty and charm. But that context was ignored by overzealous fans, who combed through her social media accounts looking for other posts to criticize, framing her as a terrible person.

After discovering through Charihe’s account that she was pregnant, Jang Wonyoung’s fans escalated their attacks by targeting her unborn child with insults.

The harassment did not stop there. Around midnight, fans doxxed Charihe, exposing her personal information, workplace, and the contact details of her family and friends. Her friends were flooded with messages, and some were even targeted at their workplaces.

Then, they tracked down Charihe’s husband’s WeChat account, sent him screenshots of her posts, and encouraged him to “physically punish” her.

The extremity of the online harassment finally drew backlash from netizens, who expressed concern for this ordinary pregnant woman’s situation:

💬 “Her entire life was exposed to people she never wanted to know about.”

💬 “Suffering this kind of attack during pregnancy is truly an undeserved disaster.”

Despite condemnation of the hate, some extreme self-proclaimed “fans” remained relentless in the online witch hunt against Charihe.

Baidu Takes a Hit After VP’s 13-Year-Old Daughter Is Exposed

One female fan, nicknamed “YourEyes” (@你的眼眸是世界上最小的湖泊), soon started doxxing commenters who had defended her. The speed and efficiency of these attacks left many stunned at just how easy it apparently is to trace social media users and doxx them.

Digging into old Weibo posts from the “YourEyes” account, people found she had repeatedly doxxed people on social media since last year, using various alt accounts.

She had previously also shared information claiming to study in Canada and boasted about her father’s monthly salary of 220,000 RMB (approx. $30.3K), along with a photo of a confirmation document.

Piecing together the clues, online sleuths finally identified her as the daughter of Xie Guangjun (谢广军), Vice President of Baidu.

From an online hate campaign against an innocent, snarky commenter, the case then became a headline in Chinese state media, and even made international headlines, after it was confirmed that the user “YourEyes”—who had been so quick to dig up others’ personal details—was in fact the 13-year-old daughter of Xie Guangjun, vice president at one of China’s biggest tech giants.

On March 17, Xie Guangjun posted the following apology to his WeChat Moments:

💬 “Recently, my 13-year-old daughter got into an online dispute. Losing control of her emotions, she published other people’s private information from overseas social platforms onto her own account. This led to her own personal information also getting exposed, triggering widespread negative discussion.

As her father, I failed to detect the problem in time and failed to guide her in how to properly handle the situation. I did not teach her the importance of respecting and protecting the privacy of others and of herself, for which I feel deep regret.

In response to this incident, I have communicated with my daughter and sternly criticized her actions. I hereby sincerely apologize to all friends affected.

As a minor, my daughter’s emotional and cognitive maturity is still developing. In a moment of impulsiveness, she made a wrong decision that hurt others and, at the same time, found herself caught in a storm of controversy that has subjected her to pressure and distress far beyond her age.

Here, I respectfully ask everyone to stop spreading related content and to give her the opportunity to correct her mistakes and grow.

Once again, I extend my apologies, and I sincerely thank everyone for your understanding and kindness.”

The public response to Xie’s apology has been largely negative. Many criticized the fact that it was posted privately on WeChat Moments rather than shared on a public platform like Weibo. Some dismissed the statement as an attempt to pacify Baidu shareholders and colleagues rather than take real accountability.

Netizens also pointed out that the apology avoided addressing the core issue of doxxing. Concerns were raised about whether Xie’s position at Baidu—and potential access to sensitive information—may have helped his daughter acquire the data she used to doxx others.

Adding fuel to the speculation were past conversations allegedly involving one of @YourEyes’ alt accounts. In one exchange, when asked “Who are you doxxing next?” she replied, “My parents provided the info,” with a friend adding, “The Baidu database can doxx your entire family.”

Following an internal investigation, Baidu’s head of security, Chen Yang (陈洋), stated on the company’s internal forum that Xie Guangjun’s daughter did not obtain data from Baidu but from “overseas sources.”

However, this clarification did little to reassure the public—and Baidu’s reputation has taken a hit. The company has faced prior scandals, most notably a the 2016 controversy over profiting from misleading medical advertisements.

Online Vulnerability

Beyond Baidu’s involvement, the incident reignited wider concerns about online privacy in China. “Even if it didn’t come from Baidu,” one user wrote, “the fact that a 13-year-old can access such personal information about strangers is terrifying.”

Using the hashtag “Reporter buys own confidential data” (#记者买到了自己的秘密#), Chinese media outlet Southern Metropolis Daily (@南方都市报) recently reported that China’s gray market for personal data has grown significantly. For just 300 RMB ($41), their journalist was able to purchase their own household registration data.

Further investigation uncovered underground networks that claim to cooperate with police, offering a “70-30 profit split” on data transactions.

These illegal data practices are not just connected to doxxing but also to widespread online fraud.

In response, some netizens have begun sharing guides on how to protect oneself from doxxing. For example, they recommend people disable phone number search on apps like WeChat and Alipay, hide their real name in settings, and avoid adding strangers, especially if they are active in fan communities.

Amid the chaos, K-pop fan wars continue to rage online. But some voices—such as influencer Jingzai (@一个特别虚荣的人)—have pointed out that the real issue isn’t fandom, but the deeper problem of data security.

💬 “You should question Baidu, question the telecom giants, question the government, and only then, fight over which fan group started this.”

As for ‘Charihe,’ whose comment sparked it all—her account is now gone. Her username has become a hashtag. For some, it’s still a target for online abuse. For others, it is a reminder of just how vulnerable every user is in a world where digital privacy is far from guaranteed.

By Ruixin Zhang

Independently covering digital China for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Insight

Squat or Sit? China’s Great Toilet Debate and the Problem of Footprints on the Seat

From squatting to standing on seats: the messy reality of sitting toilets in Beijing malls.

Published

5 days agoon

March 25, 2025

FROM THE WEIBO WATCH PREMIUM NEWSLETTER

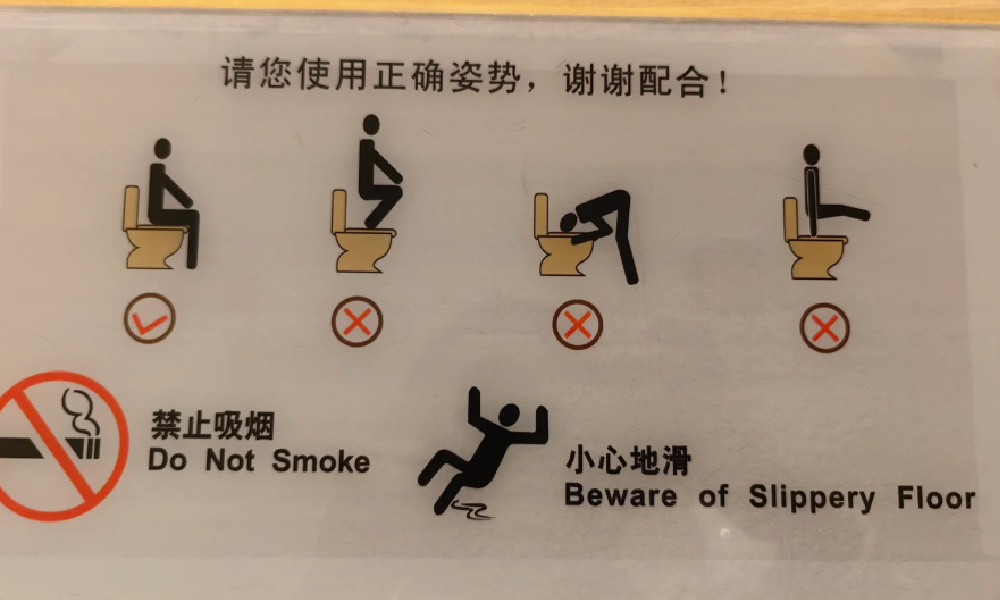

Shoe prints on top of the toilet seat are never a pretty sight. To prevent people from squatting over Western-style sitting toilets, there are some places that will place stickers above the toilet, reminding people that standing on the seat is strictly forbidden.

For years, this problem has sparked debate. Initially, these discussions would mostly take place outside of China, in places with a large number of Chinese tourists. In Switzerland, for example, the famous Rigi Railways caused controversy for introducing separate trains with special signs explaining to tourists, especially from China, how (not) to use the toilet.

Squat toilets are common across public areas in China, especially in rural regions, for a mix of historical, cultural, and practical reasons. There is also a long-held belief — backed by studies (like here or here) — that the squatting position is healthier for bowel movements (for more about the history of squat toilets in China, see Sixth Tone’s insightful article here).

Public squatting toilets in Beijing, images via Xiaohongshu.

Without access to the ground-level squat toilets they are used to — and feel more comfortable with — some people will climb on top of sitting toilets to use them in the way they’re accustomed to, seeing squatting as the more natural and hygienic method.

Not only does this make the toilet seat all messy and muddy, it is also quite a dangerous stunt to pull, can break the toilet, and lead to pee and poo going into all kinds of unintended directions. Quite shitty.

Squatting on toilets makes the seat dirty and can even break the toilet.

Along with the rapid modernization of Chinese public facilities and the country’s “Toilet Revolution” over the past decade, sitting toilets have become more common in urban areas, and thus the sitting-toilet-used-as-squat-toilet problem is increasingly becoming topic of public debate within China.

The Toilet Committee and Preference for Sitting Toilets

Is China slowly shifting to sitting toilets? Especially in modern malls in cities like Beijing, or even at airports, you see an increasing number of Western-style sitting toilets (坐厕) rather than squatting toilets (蹲厕).

This shift is due to several factors:

🚽📌 First, one major reason for the rise in sitting toilets in Chinese public places is to accommodate (foreign) tourists.

In 2015, China Daily reported that one of the most common complaints among international visitors was the poor condition of public toilets — a serious issue considering tourists are estimated to use public restrooms over 27 billion times per year.

That same year, China’s so-called “Toilet Revolution” (厕所革命) began gaining momentum. While not a centralized campaign, it marked a nationwide push to upgrade toilets across the country and improve sanitation systems to make them cleaner, safer, and more modern.

This movement was largely led by the tourism sector, with the needs of both domestic and international travelers in mind. These efforts, and the buzzword “Toilet Revolution,” especially gained attention when Xi Jinping publicly endorsed the campaign and connected it to promoting civilized tourism.

In that sense, China’s toilet revolution is also a “tourism toilet revolution” (旅游厕所革命), part of improving not just hygiene, but the national image presented to the world (Cheng et al. 2018; Li 2015).

🚽📌 Second, the growing number of sitting toilets in malls and other (semi)public spaces in Beijing relates to the idea that Western-style toilets are more sanitary.

Although various studies comparing the benefits of squatting and sitting toilets show mixed outcomes, sitting toilets — especially in shared restrooms — are generally considered more hygienic as they release fewer airborne germs after flushing and reduce the risk of infection (Ali 2022).

There are additional reasons why sitting toilets are favored in new toilet designs. According to Liang Ji (梁骥), vice-secretary of the Toilet Committee of the China Urban Environmental Sanitation Association (中国城市环境卫生协会厕所专业委员会), sitting toilets are also increasingly being introduced in public spaces due to practical concerns.

🚽📌 Squatting is not always easy, and can pose a safety risk, particularly for the elderly, pregnant women, and people with disabilities.

🚽📌 Then there are economic reasons: building squat toilets in malls (or elsewhere) requires a deeper floor design due to the sunken space needed below the fixture, which increases both construction time and cost.

🚽📌 Liang also points to an aesthetic factor: sitting toilets simply look more “high-end” and are easier to clean, which is why many consumer-oriented spaces prefer to install Western-style toilets.

So although there are plenty of reasons why sitting toilets are becoming a norm in newly built public spaces and trendy malls, they also lead to footprints on toilet seats — and all the problems that come with it.

The Catch 22 of Sitting vs Squad Toilets

This week, the issue became a trending topic on Weibo after Beijing News published an investigative report on it. The report suggested that most shopping malls in Beijing now have restrooms with sitting toilets, which should, in theory, be cleaner than the squat toilets of the past — but in reality, they’re often dirtier because people stand on them. This issue is more common in women’s restrooms, as men’s restrooms typically include urinals.

In researching the issue, a reporter visited several Beijing malls. In one women’s restroom, the reporter observed 23 people entering within five minutes. Although the restroom had only three squat toilets versus seven sitting ones, around 70% of the users opted for the squat toilets.

Upon inspection, most of the seven sitting toilets were dirty — despite being equipped with disposable seat covers — showing clear signs of urine stains and footprints. They found that sitting toilets being used as squat toilets is extremely common.

It’s a bit of a Catch-22. People generally prefer clean toilets, and there’s also a widespread preference for squat toilets. This leads to sitting toilets being used as squat toilets, which makes them dirty — reinforcing the preference for squat toilets, since the sitting toilets, though meant to be cleaner, end up dirtier.

In interviews with 20 women, nearly 80% said they either hover in a squat or directly squat on the toilet seat. One woman said, “I won’t sit unless I absolutely have to.” While some of those quoted in the article said that sitting toilets are more comfortable, especially for elderly people, they are still not preferred when the seats are not clean.

In the Beijing News article, the Toilet Committee’s Liang Ji suggested that while a balanced ratio of squat and sitting toilets is necessary, a gradual shift toward sitting toilets is likely the future for public restrooms in China.

How NOT to use the sitting toilet. Sign photographed by Xiaohongshu user @FREAK.00.com.

Liang also highlighted the importance of correct toilet use and the need to consider public habits in toilet design.

In Squatting We Trust

On Chinese social media, however, the majority of commenters support squatting toilets. One popular comment said:

💬 “Please make all public toilets squat toilets, with just one sitting toilet reserved for people with disabilities.”

Squatting toilets in a public toilet in a Beijing hutong area, image by Xiaohongshu user @00后饭桶.

The preference for squatting, however, doesn’t always come down to bowel movements or tradition. Many cite a lack of trust in how others use public toilets:

💬 “When it comes to things for public use, it’s best to reduce touching them directly. Honestly, I don’t trust other people…”

💬 “Squatting is the most hygienic. At least I don’t have to worry about touching something others touched with their skin.”

💬 “I hate it when all the toilets in the women’s restroom at the mall are sitting toilets. I’m almost mastering the art of doing the martial-arts squat (蹲马步).”

Others view the gradual shift toward sitting toilets as a result of Westernization:

💬 “Sitting toilets are a product of widespread ‘Westernization’ back in the day — the further south you go, the worse it gets.”

But some come to the defense of sitting toilets:

💬 “Are there really still people who think squat toilets are cleaner? The chances of stepping in poop with squat toilets are way higher than with sitting ones. Sitting toilet seats can be wiped with disinfectant or covered with paper. Some people only care about keeping themselves ‘clean’ without thinking about whether the next person might end up stepping in their mess.”

💬 One reply bluntly said: “I don’t use sitting toilets. If that’s all there is, I’ll just squat on top of it. Not even gonna bother wiping it.”

It’s clear this debate is far from over, and the issue of people standing on toilet seats isn’t going away anytime soon. As China’s toilet revolution continues, various Toilet Committees across the country may need to rethink their strategies — especially if they continue leaning toward installing more sitting toilets in public spaces.

As always, Taobao has a solution. For just 50 RMB (~$6.70), you can order an anti-slip sitting-to-squatting toilet aid through the popular e-commerce platform.

The Taobao solution.

For Chinese malls, offering these might be cheaper than dealing with broken toilets and the never-ending battle against footprints on toilet seats…

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

References:

Ali, Wajid, Dong-zi An, Ya-fei Yang, Bei-bei Cui, Jia-xin Ma, Hao Zhu, Ming Li, Xiao-Jun Ai, and Cheng Yan. 2022. “Comparing Bioaerosol Emission after Flushing in Squat and Bidet Toilets: Quantitative Microbial Risk Assessment for Defecation and Hand Washing Postures.” Building and Environment 221: 109284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109284.

Bhattacharya, Sudip, Vijay Kumar Chattu, and Amarjeet Singh. 2019. “Health Promotion and Prevention of Bowel Disorders Through Toilet Designs: A Myth or Reality?” Journal of Education and Health Promotion 8 (40). https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_198_18.

Cao, Jingrui 曹晶瑞, and Tian Jiexiong 田杰雄. 2025. “城市微调查|商场女卫生间,坐厕为何频频变“蹲坑”? [In Shopping Mall Women’s Restrooms, Why Do Sitting Toilets Frequently Turn into ‘Squat Toilets’?]” Beijing News, March 20. https://weibo.com/ttarticle/p/show?id=2309405146044773302810. Accessed March 19, 2025.

Cheng, Shikun, Zifu Li, Sayed Mohammad Nazim Uddin, Heinz-Peter Mang, Xiaoqin Zhou, Jian Zhang, Lei Zheng, and Lingling Zhang. 2018. “Toilet Revolution in China.” Journal of Environmental Management 216: 347–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.09.043.

Dai, Wangyun. 2018. “Seats, Squats, and Leaves: A Brief History of Chinese Toilets.” Sixth Tone, January 13. https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1001550. Accessed March 22, 2025.

Li, Jinzao. 2015. “Toilet Revolution for Tourism Evolution.” China Daily, April 7. https://europe.chinadaily.com.cn/opinion/2015-04/07/content_20012249_2.htm. Accessed March 22, 2025.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Popular Reads

-

China Insight11 months ago

China Insight11 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music12 months ago

China Music12 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

-

China Arts & Entertainment11 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment11 months agoSinging Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

benny ferdy malonda

June 30, 2016 at 10:27 am

Hi, Dr Pei,

Firstly greet from me. I wonna know whether you are a mediacal anthropologist and medical doctor.

Actually i am interested in your paper above, thtat related to health and mediacal science, however because

you write about habit and culture related to health, that is an mediacal anthropology theory. But, of course

you write an interesting paper as research result

Best regards, benny