China Arts & Entertainment

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

“I’m in Zibo eating barbecue, I really don’t feel like listening to Alicia Keys.” Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ has set off a new wave of national pride in China’s music and performers.

Published

10 months agoon

By

Ruixin Zhang

Besides memes and jokes, Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ has set off a new wave of national pride in China’s music and performers on Chinese social media.

In May, while the whole of Europe was gripped by the Eurovision Song Contest frenzy, Chinese audiences were eagerly anticipating the return of their own beloved singing competition, Singer 2024 (@湖南卫视歌手), formerly known as I Am a Singer (我是歌手).

The show, introduced from South Korea’s MBC Television and popular in China since 2013, only features professional singers who have already made a name for themselves.

Rather than watching unknown aspiring singers who are hoping to be discovered in many singing competitions, such as Sing! China, Singer 2024 gives audiences a show filled with professional and often stunning show performances by established names in the entertainment industry.

Since 2013, renowned singers from China and abroad have appeared on the show, including Chinese vocalist Tan Jing (谭晶), British pop singer Jessie J, and the late Hong Kong pop diva Coco Lee. However, no season managed to create as many waves as the 2024 season did, dominating all social media trending topics overnight.

So, what exactly happened?

COMPETING WITH FOREIGNERS

“The difference between the Grammys and the Strawberry Musical Festival”

In early May, the pre-show promotion of Singer 2024 was already buzzing on Chinese social media after a list of featured singers appeared on Weibo, including big names such as American singer-songwriter Bruno Mars, Korean-New Zealand singer Rosé from Blackpink, and Japanese diva LiSA.

Although Singer previously had many foreign singers on the show, this international celebrity lineup still caused a stir.

On the day of the first episode, only two foreign singers were announced to appear on the show: young Moroccan-Canadian singer Faouzia and the Grammy-nominated American singer-songwriter Chanté Moore. The other contestants were all Chinese singers who are already well-known among Chinese audiences. Because many people were unfamiliar with the two foreign singers, they joked that the winner of this season was already set in stone; surely it would be the famous Chinese singer Na Ying (那英), known for her beautiful voice.

However, that first episode surprised everyone as the two foreign singers, Faouzia and Chanté Moore, showed outstanding vocal skills. This not only startled many viewers but also made the Chinese contestants uneasy. Several experienced Chinese singers apparently were so unnerved after watching Faouzia and Chanté Moore’s performance that their voices trembled when singing.

Since the show was broadcast live – without post-production editing or autotune – audiences got to hear the actual vocal capabilities and see performers’ genuine reactions. It seemed undeniable that the foreign contestants did much better in terms of vocals and stage presence than the Chinese ones. Some online commenters even said that the gap between Chinese and foreign singers’ levels was like “the difference between the Grammys and the Strawberry Musical Festival” [a local Chinese music festival].

Chinese online influencer Yongkai (@陈咏开165) shared screenshots of Chanté Moore’s backstage reactions during the show. The American celebrity seemed puzzled when hearing the somewhat underwhelming performance by Chinese singer Yang Chenglin (楊丞琳), and she appeared much more positive when Na Ying sang.

This noteworthy scene, coupled with Chanté’s comments during an interview saying that she thought the Chinese production team had invited her on the show to be a judge, turned the entire show into a display of foreign singers outshining the Chinese contestants.

By the end of the first episode, Chanté Moore and Faouzia unsurprisingly ranked first and second, with Na Ying in third place.

After the show, some online commenters jokingly pointed out that Na Ying, being of Manchu descent like the rulers of China during the Qing Dynasty, showed some similarities to Empress Dowager Cixi’s defiance against Western colonizers in the way she “single-handedly took up against on foreigners” on the show.

They humorously turned Na Ying’s expressions into memes resembling Empress Dowager Cixi from an old Chinese TV show, with captions like “I want the foreigners dead” (“我要洋人死”).

Others suggested finding better Chinese singers for the show who could compete with Faouzia and Moore.

“SINGING WELL” CULTURALLY COLONIZED?

“I’m in Zibo eating BBQ, I really don’t want to listen to Alicia Keys.”

Initially, discussions about the show were light-hearted and humorous, until some netizens who couldn’t appreciate the jokes began to dampen the mood and made online discussions more serious.

Zou Xiaoying (@邹小樱), a music critic with nearly two million followers, posted on social media after the show, stating that he would have never voted for Chanté Moore or Faouzia. Not only did Zou question their vocal talent, he also wondered if the aesthetic of Chinese listeners had been influenced by Western music taste to such an extent that it has been “culturally colonized” (“文化殖民”). Meanwhile, he praised the members of Beijing rock band Second Hand Rose as “national heroes” (“民族英雄”).

He wrote:

If I had three votes for the first episode of “Singer 2024,” I’d vote for Second Hand Rose, Na Ying, and Silence Wang [note: Chinese singer-songwriter and record producer Wang Sushuang 汪苏泷]. The reason I wouldn’t vote for Chanté Moore or Faouzia is because — do they actually sing so well?

Has our definition of “singing well” perhaps been colonized? Just as our modern-day use of Chinese has little to do with our classical Chinese poems, with the foundation of modern Chinese actually being translations from the 20th century, is this also a form of ‘cultural colonization’?

You must think I’m talking nonsense again. But when I listen to Chanté Moore singing “If I Ain’t Got You,” I find it too boring. I know her singing is “good,” but this “good” has nothing to do with me. If, for Chinese listeners, Chanté Moore’s “good” is the standard, then is that what we in the music industry should be working towards? Isn’t that funny? When you open QQ Music or NetEase Cloud Music, and it recommends these songs to you every day, won’t you be convinced to practice again?

Of course, I know Chanté Moore is in good shape, very relaxed. Actually all of the Chinese singers tonight were very nervous. Yang Chenglin (杨丞琳) was nervous, Na Ying was also nervous. Even a seemingly carefree band like Second Hand Rose, if you listened to the introduction of their song, [you’ll find] they were so nervous that Yao Lan, supposedly “China’s No.1 Guitarist”, was so nervous that he hit the wrong note. It was not even a fast-paced solo (…), how nervous could he be? When everyone’s so tense, the confidence of Chanté Moore and Faouzia is indeed something that East Asia can’t match. In East-Asian [entertainment] circles, represented by China/Japan/Korea, our different cultural habits, upbringing, and ethnic characteristics have made it so that we don’t possess these kinds of singing abilities, even including our ways of emotional expression. I don’t know from which season it started with ‘Singer’ – and if it’s some kind of Catfish Effect (鲶鱼效应 ) – that they brought international singers with different cultural backgrounds into the competition. But this isn’t the Olympics, it’s not like Liu Xiang [刘翔, Chinese gold medal hurdler] is going to defeat opponents from the United States or Cuba. “I’m in Zibo eating barbecue, I really don’t feel like Alicia Keys.” (This line is not mine, I stole it from my WeChat friend).

Because of this, I find Second Hand Rose even more rare and precious. It’s just like I used to love asking: If you could only recommend one Chinese band to your foreign friends, which one would you recommend? Some say it’s New Pants (新裤子), some say it’s Omnipotent Youth Society, but my answer will always be Second Hand Rose. ‘The drama of Monkey King is a national treasure,’ its light will always shine. Facing the gunfire of Western powers, Second Hand Rose is standing on the frontline, they are our national heroes. Indeed, the band itself was nervous, (..), but when Chanté Moore goes off like a singing dolphin, we are fortunate to have Second Hand Rose at the frontline; the Chinese sons and daughters are building the Great Wall of Music of flesh and blood.

Because of this, I find Second Hand Rose even more rare and precious. It’s just like I used to love asking: If you could only recommend one Chinese band to your foreign friends, which one would you recommend? Some say it’s New Pants (新裤子), some say it’s Omnipotent Youth Society, but my answer will always be Second Hand Rose. ‘The drama of Monkey King is a national treasure,’ its light will always shine. Facing the gunfire of Western powers, Second Hand Rose is standing on the frontline, they are our national heroes. Indeed, the band itself was nervous, (..), but when Chanté Moore goes off like a singing dolphin, we are fortunate to have Second Hand Rose at the frontline; the Chinese sons and daughters are building the Great Wall of Music of flesh and blood.

Anyway, no matter if they’re strong or not, I would never vote for the foreigner.

The comment about ‘I’m in Zibo eating barbecue, I really don’t feel like [listening to] Alicia Keys’ refers to the craze surrounding China’s ‘BBQ town’ Zibo. In Zibo, Chinese visitors like to sing, drink beer, and enjoy food together; it’s a simple and modest way of appreciating life and music, which contrasts with slick and smooth American or foreign styles of performing and singing.

Whether Zou’s criticism was for attention or genuine sentiment, it shifted the focus of the discussion from music to patriotism.

CHINESE SINGERS WITH MILITARISTIC UNDERTONES

“I volunteer to join the battle”

Amidst all this, some netizens, easily swayed by nationalist sentiments, began to seek help from the “national team” (国家队) of singers — musicians employed by national-level arts troupes — to “bring glory to the nation” and teach the foreigners a lesson. Some even questioned the intentions of the Singer 2024 TV show in inviting foreign singers to participate.

On May 12th, renowned Chinese singer and philanthropist Han Hong (韩红) posted on Weibo, fueling a wave of sentiment and support. In her post, Han Hong declared, “I am Chinese singer Han Hong, and I volunteer to join the battle,” tagging the production team of the TV show. Her invitation to join the battle quickly went viral.

Han Hong meme: “Who called for me?”

Han Hong has significant influence in the Chinese music industry and society as a whole. Her usual serious demeanor and avoidance of internet pop culture made netizens unsure whether she was joking or serious. Nevertheless, regardless of her intentions, a group of well-known singers began to volunteer via Weibo, emphasizing their identity as “Chinese singers” and using phrases with strong militaristic undertones like “fighting for the country” and “answering the call.”

Although many enjoyed this new wave of national pride in Chinese music and performers, some netizens criticized the trend of transforming an entertainment show into a nationalistic competition.

Film critic He Xiaoqin (何小沁) stated, “It’s okay to take the Qing-Dynasty-fighting-foreigners comparison as a joke, but taking it too seriously in today’s context is absurd.”

Others expressed fatigue with how quickly topics on Chinese internet platforms escalate to patriotic sentiments. To bring the focus back to entertainment, they turned “I volunteer to join the battle” (#我请战#) into a new internet catchphrase.

In response, the production team of Singer 2024 released a statement on Weibo, thanking all the singers for their self-recommendations. They emphasized the show’s competitive structure but clarified that “winning” is just one part of a singer’s journey..but that the love of music goes beyond all in connecting people, no matter where they’re from.

By Ruixin Zhang, edited with further input by Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Ruixin is a Leiden University graduate, specializing in China and Tibetan Studies. As a cultural researcher familiar with both sides of the 'firewall', she enjoys explaining the complexities of the Chinese internet to others.

You may like

-

The Unstoppable Success of Ne Zha 2: Breaking Global Records and Sparking Debate on Chinese Social Media

-

The ‘China-chic Girl’ Image and the Realities of China’s Competitive Food Delivery Market

-

Why Chinese Hit Movie “Her Story” is ‘Good Stuff’: Stirring Controversy and Celebrating Female Perspectives

Chinese Movies

The Unstoppable Success of Ne Zha 2: Breaking Global Records and Sparking Debate on Chinese Social Media

Everyone’s talking about Ne Zha 2—from in-depth online analyses to the booming market surrounding the film.

Published

1 day agoon

February 25, 2025

China’s animated blockbuster Ne Zha 2 (哪吒之魔童闹海) is smashing box office records and igniting debates on Chinese social media—from its most popular supporting characters to the question of which town can truly claim Nezha as its own.

The Chinese animation blockbuster Ne Zha 2 (哪吒之魔童闹海) has been a major point of discussion in China recently—not just for the movie itself, but also for its box office performance, which has become a hot topic on Weibo and beyond.

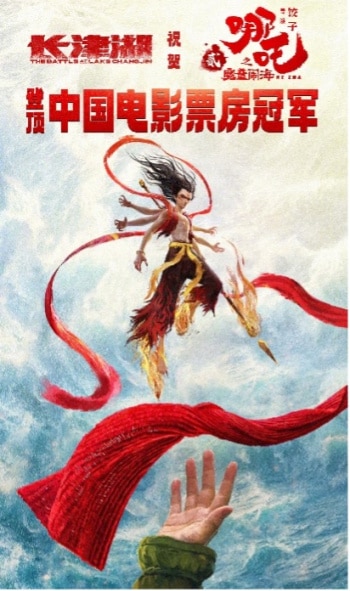

Just nine days after its release on January 29, Ne Zha 2 had already surpassed the 2021 film The Battle at Lake Changjin (长津湖), which had previously held the title of the highest-grossing Chinese film of all time—surpassing Wolf Warrior 2 (战狼2).

China’s top 3 highest-grossing movies: Ne Zha 2, Battle at Lake Changjin, and Wolf Warrior 2

In mid-February, Chinese netizens were eagerly anticipating Ne Zha 2 reaching the 10 billion yuan milestone (about $1.37 billion). At the time, the film had already grossed over 9.8 billion yuan ($1.35 billion), securing its place as the 17th highest-grossing film worldwide and the only non-Hollywood film in the top 20.

Now, the film’s global box office performance has surpassed all expectations: it has exceeded 13.8 billion yuan ($1.90 billion) as of February 25, placing Ne Zha 2 among the top eight highest-grossing films of all time worldwide. On Tuesday, it already became the highest-grossing animated film in global history.

In response to the film’s overwhelming success, there have been all kinds of memes, trends, and hashtags on Chinese on social media.

The official Weibo account of The Battle at Lake Changjin published a post to congratulate Ne Zha 2 making new record for Chinese cinema history. This tradition is known as the “Box Office Champion Poster Relay,” originally initiated by Chinese director Xu Zheng (徐峥) in 2015 with the hope of fostering camaraderie and encouragement among filmmakers in China.

On February 6, the official Weibo account of The Battle at Lake Changjin published a post to congratulate Ne Zha 2 making new record for Chinese cinema history.

Earlier in February, Weibo users created the hashtag “The Least Educated Film Star of All Time” (#史上学历最低的影帝#) to celebrate Nezha—a 3-year-old mythological hero.

With the combined success of Nezha 1 and Nezha 2, they jokingly call Nezha the ‘youngest character’ to ever surpass the 10-billion-yuan box office milestone.

One popular comment said:

“Congratulations! The least educated film star in history (didn’t even finish kindergarten), and the youngest one to hold a 10-billion-yuan box office record, is our darling little Nezha.”

Nezha 2 is directed by Yang Yu (杨宇), also known as Jiaozi (饺子), and co-produced by Coco Cartoon (可可豆动画), Coloroom Pictures (彩条屋影业), and others. Released during the Spring Festival holiday, the film continues the storyline from its 2019 predecessor Nezha 1.

Based on Chinese mythology, the film follows the legendary figures Nezha (哪吒) and Ao Bing (敖丙), both characters from 16th-century classic Chinese novel Investiture of the Gods (封神演义). This narrative delves into the history of the Shang (c. 1600-c. 1046 BC) and Zhou (c. 1046-771 BC) dynasties, weaving together folklore, legends, and a variety of mythical beings and creatures.

Nezha and Ao Bing face a dire crisis—their souls remain intact, but their bodies are on the brink of disintegration. To save them, Nezha’s master, Taiyi Zhenren (太乙真人), plans to restore their forms using the mystical Seven-Colored Lotus.

The protagonist, Nezha, is a prominent figure from Chinese mythology and folklore. Besides in Investiture of the Gods, he also appears in Journey to the West (西游记). In Taiwan, Nezha is often revered as the “Third Prince” (三太子, Sān Tàizǐ), as he is the third son of Li Jing (李靖), also known as the Pagoda-Bearing Heavenly King Li (托塔李天王), in these mythological tales.

Ne Zha 2 promo image, China Daily.

Ne Zha 1 and Ne Zha 2 are not the first animated works centered around the character of Nezha.

The 1979 classic film Nezha Conquers the Dragon King (哪吒闹海), produced by Shanghai Animation Film Studio (上海美术电影制片厂), was China’s first large-scale color widescreen animated feature. It depicted Nezha’s conflict with the ‘Dragon King of the East Sea’ (东海龙王) and included the iconic scene where Nezha returns his bones to his father and flesh to his mother. His self-sacrifice in white robes is regarded as one of the most powerful moments in Chinese animation history. With its traditional Chinese aesthetics, this version of Nezha remains a beloved classic, particularly among those born in the 1970s and 1980s.

An important scene of “Nezha Conquers the Dragon King,” where Nezha is about to sacrifice himself to protect the people of Chentang Pass.

For those born in the 1990s and 2000s, childhood memories of Nezha are often linked to the 2003 animated TV series The Legend of Nezha (哪吒传奇), produced by China International Television Corporation. The theme song of this 52-episode series, “Young Hero Nezha” (少年英雄小哪吒), remains a nostalgic tune familiar to many from that era.

The Legend of Nezha

The shared cultural memory of Nezha, along with the overwhelmingly positive reception of Ne Zha 1 in 2019, has undoubtedly laid a strong foundation for the success of Ne Zha 2. Combined with five years of dedicated production—with some one-minute scenes taking up to six months (!) to conceptualize—it seems Ne Zha 2 was destined for cinematic success.

The Evolution of Nezha

Chinese audiences have had a variety of reactions to Ne Zha 2. Many viewers have expressed their love for the film, with some claiming to have watched it multiple times—some as many as six times—in different cinema formats to find the best viewing experience.

Some have found unique interpretations of some of the film’s details. Under various hashtags (e.g. #哪吒2隐喻引热议#), netizens actively discuss and analyze references in the film. These include a dollar sign-like symbol on the celestial artifact Tianyuan Ding (天元鼎) and scenes that seem to allude to the Bretton Woods system, sparking speculation that the film hints at global economic dynamics.

Hidden messages in Ne Zha 2? Some netizens think there are.

Not all feedback has been positive. Some viewers have criticized the film for how it prioritizes traditional values like filial piety in Nezha’s character rather than rebellion, feeling it does not really suit the spirit of his character.

One Weibo commenter (@我不是小日王) wrote:

“I’m not sure if I can say this, but honestly, I don’t really like the changes made to the story line in Nezha 2. In my memory, Nezha was not just the super strong and determined god of the Three Altar Sea Gathering, but also a lonely wanderer. Despite being deeply influenced by Confucian culture, where “filial piety is the greatest virtue” (百善孝为先), he still displayed rebellious behavior going against all morality by returning his flesh to his father and bones to his mother. He’s a genuine pioneer in rejecting patriarchal society (as referenced in Jiang Xun’s Six Lectures on Loneliness). But [in Nezha 2], to make him more relatable to the masses, he is forcibly portrayed as a filial, harmonious, superhero-like little boy.”

The movie’s fighting scenes and the depiction of Nezha as an overly reckless character have also drawn some disapproval. One Weibo user wrote:

“After watching the first film, I thought it was good—a troublemaking demon child defying fate to save the world. After going through so much, you’d at least expect some character growth. But in the second film, he’s still looking for trouble, throwing tantrums whenever he faces difficulties, and howling all the time. I honestly don’t see any charm in his character at all.”

Despite the success of Ne Zha 2, for those who already had a favorite version of Nezha, the changes to the character might be a bit harder to accept.

Beijing Business Newspaper (北京商报) recently posted an overview on Weibo of Nezha’s evolution, suggesting that “every generation has its own Nezha.” From the arrogant deity in the 1961 Havoc in Heaven (大闹天宫) to the defiant rebel in the 1979 Nezha Conquers the Dragon King (哪吒闹海) or the clever and courageous young hero in the 2003 The Legend of Nezha (哪吒传奇), the character has continuously evolved with the times.

From “Small-town Swot” to Stone Diva

It is not only the figure of Nezha that has dominated discussions surrounding Ne Zha 2. Some of the other characters in the film are also resonating with audiences and have become a popular topic of discussion on Chinese social media.

One of the most beloved characters is Shen Gongbao (申公豹). A villain in the first film, Ne Zha 2 adds more depth to his character, leading many viewers to empathize with his struggles.

As a hardworking overachiever with a stutter, not particularly born into privilege like many of the celestial figures in the film, some Chinese netizens suggest that he represents the experience of many “small-town swots” (xiǎozhèn zuòtíjiā 小镇做题家) in China.

Shen Gongbao (申公豹) has become China’s most beloved villain.

“Small-town swot” is a buzzword that has appeared on Chinese social media over the past few years, first popping up on a Douban forum. It refers to students from rural areas and small towns in China who put in immense effort to secure a place at a top university and move to bigger cities. While they may excel academically, even ranking as top scorers, they often struggle to gain social advantages, highlighting a deeper rural-urban divide in China.

Initially used in a self-deprecating manner, the term became a way for people from modest backgrounds to vent their frustrations and self-doubt, eventually striking a chord with many others.

There is now a series of hashtags about Shen Gongbao being a small-town swot (#申公豹 小镇做题家#, #申公豹丑强惨#, #申公豹 真男人#), all adding to the popularity of this character.

Another standout character is Lady Stone (石矶娘娘), a larger-than-life demon whom Nezha must overcome in his celestial trials. She has gained attention for her grand, imposing presence – a bold and diva-like figure who once was a stone.

Lady Stone from Ne Zha 2, and the fan art dedicated to her.

Lady Stone first appears questioning a magic mirror about her beauty, and after being defeated by Nezha, she ultimately accepts her unique form. Some Chinese netizens see her as a challenge to traditional beauty standards, leading to the hashtag “Lady Stone Breaks Beauty Stereotypes” (#石矶娘娘打破白幼瘦审美枷锁#) and countless fan art contributions, celebrating her as a symbol of self-acceptance and female resilience.

The Rise of “Ne Zha Economy”

As the box office success of Ne Zha 2 continues to skyrocket, its economic impact is becoming increasingly evident.

By early February, the film had already generated most of the annual revenue for its production company, Enlight Media (光线传媒). The company’s shares hit an all-time high, soaring over 150% in just six trading days. With box office numbers still rising, Enlight Media’s profits are expected to grow even further, signaling a strong financial outlook.

The film’s success has also had a positive impact on cinema chains. Hengdian Entertainment (横店影视) hit the daily trading limit, while Wanda Film (万达电影) and Bona Film Group (博纳影业) saw their shares rise by over 6%. Other companies in the sector also experienced stock price gains.

Beyond the box office, Ne Zha 2 has driven a surge in related merchandise sales. The film’s characters appear in numerous commercial ads, and Pop Mart’s (泡泡玛特) Ne Zha 2 blind box figurines have been so popular that many stores are down to display items only. Pop Mart’s stock price also hit a new high, significantly boosting its market value.

The Ne Zha 2 blind box figurines from Pop Mart.

In terms of tourism, several regions across China are also looking to capitalize on the film’s popularity. Since Chentang Pass (陈塘关), Nezha’s birthplace in Investiture of the Gods, lacks a clearly defined real-world location, multiple cities are hoping to claim the title of “Nezha’s hometown” (#多地争给哪吒上户口#).

Because Tianjin is a sea city that has a place called “Chentangzhuang”, it already started to promote itself on social media as being Nezha’s birthplace with the hashtag: “Nezha’s Hometown, Tianjin, Invites You to Visit” (#哪吒故里天津喊你来打卡#).

Meanwhile, residents of Chengdu argue that their city is Nezha’s true “home”, since Ne Zha 2 was registered in Chengdu, the director is a native of Sichuan, and the production team, Coco Cartoon, is based in Gazelle Digital Cultural and Creative Valley located in Chengdu’s Tianfu Software Park.

The film is undeniably a “Chengdu-made” production, with elements of Sichuan culture woven throughout, from Taiyi Zhenren’s Sichuan-accented Mandarin to the two Boundary Beasts that look like the bronze masks of Sanxingdui, and the bamboo chairs, covered tea bowls, and flying eaves of Sichuanese architecture in Chentang Pass.

The appearance of two Boundary Beasts (结界兽, Jie2 Jie4 Shou4) is inspired by the bronze masks of Sanxingdui.

For cities with no claim to Nezha’s birthplace, local tourism campaigns have instead spotlighted Nezha temples as must-visit attractions.

How ‘International’ is Ne Zha’s Global Success?

What’s still in store for Ne Zha 2? The Chinese film industry analytics platform Maoyan predicts that the final box office earnings for Ne Zha 2 in mainland China could reach 16 billion yuan ($2.2 billion).

If this figure becomes a reality, the film wouldn’t just be the highest-grossing animated movie—it would also rank among the top five highest-grossing films in global box office history.

But how much of its box office success is truly global? Outside of China, Ne Zha 2 began its international release in mid-February 2025, with a limited release in markets like the United States, Australia, and New Zealand.

By February 20, Deadline reported that $1.72 billion of its earnings came from China alone, indicating that the vast majority of its box office revenue is domestically driven.

However, if anyone questions the significance of the international market’s contribution to Ne Zha 2’s success, they might receive a response similar to that of Wu Jing (吴京), director of the Wolf Warrior (战狼) series. When faced with skepticism about Wolf Warrior 2 making it into the top 100 global box office hits despite 99% of its earnings coming from mainland China, he simply replied:

“So what? That’s still money” (#所以呢 不是钱吗#).

By Wendy Huang

Follow @whatsonweibo

With contributions from Manya Koetse and edited for clarity

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

China ACG Culture

“Black Myth: Wukong”: From Gaming Screens to the CMG Spring Festival Gala?

Published

1 month agoon

January 21, 2025

FROM THE WEIBO WATCH PREMIUM NEWSLETTER

Is Chinese game sensation ‘Black Myth Wukong’ making a jump from gaming screens to the CMG Spring Festival Gala? There’s already some online excitement over a potential performance at the biggest liveshow of the year.

The countdown to the most-watched show of the year has begun. On January 29, the Year of the Snake will be celebrated across China, and as always, the CMG Spring Festival Gala, broadcast on CCTV1, will air on the night leading up to midnight on January 28.

Rehearsals for the show began last week, sparking rumors and discussions about the must-watch performances this year. Soon, the hashtag “Black Myth: Wukong – From New Year’s Gala to Spring Festival Gala” (#黑神话悟空从跨晚到春晚#) became a topic of discussion on Weibo, following rumors that the Gala will feature a performance based on the hugely popular game Black Myth: Wukong.

Three weeks ago, a 16-minute-long Black Myth: Wukong performance already was a major highlight of Bilibili’s 2024 New Year’s Gala (B站跨年晚会). The show featured stunning visuals from the game, anime-inspired elements, special effects, spectacular stage design, and live song-and-dance performances. It was such a hit that many viewers said it brought them to tears. You can watch that show on YouTube here.

While it’s unlikely that the entire 16-minute performance will be included in the Spring Festival Gala (it’s a long 4-hour show but maintains a very fast pace), it seems highly possible that a highlight segment of the performance could make its way to the show.

Recently, Black Myth: Wukong was crowned 2024’s Game of the Year at the Steam Awards. The game is nothing short of a sensation. Officially released on August 20, 2024, it topped the international gaming platform Steam’s “Most Played” list within hours of its launch. Developed by Game Science, a studio founded by former Tencent employees, Black Myth: Wukong draws inspiration from the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West. This legendary tale of heroes and demons follows the supernatural monkey Sun Wukong as he accompanies the Tang Dynasty monk Xuanzang on a pilgrimage to India to retrieve Buddhist scriptures. The game, however, focuses on Sun Wukong’s story after this iconic journey.

The success of Black Myth: Wukong cannot be overstated—I’ve also not seen a Chinese video game be this hugely popular on social media over the past decade. Beyond being a blockbuster game it is now widely regarded as an impactful Chinese pop cultural export that showcases Chinese culture, history, and traditions. Its massive success has made anything associated with it go viral—for example, a merchandise collaboration with Luckin Coffee sold out instantly.

If Black Myth: Wukong does indeed become part of the Spring Festival Gala, it will likely be one of the most talked-about and celebrated segments of the show. If it does not come on, which we would be a shame, we can still see a Black Myth performance at the pre-recorded Fujian Spring Festival Gala, which will air on January 29.

Lastly, if you’re not into video games and not that interested in watching the show, I still highly recommend that you check out the game’s music. You can find it on Spotify (link to album). It will also give you a sense of the unique beauty of Black Myth: Wukong that you might appreciate—I certainly do.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

What’s on Weibo Chapters

Subscribe

The Unstoppable Success of Ne Zha 2: Breaking Global Records and Sparking Debate on Chinese Social Media

From Weibo to RedNote: The Ultimate Short Guide to China’s Top 10 Social Media Platforms

Collective Grief Over “Big S”

Tuning Into the Year of the Snake

The ‘China-chic Girl’ Image and the Realities of China’s Competitive Food Delivery Market

Our Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Why Chinese Hit Movie “Her Story” is ‘Good Stuff’: Stirring Controversy and Celebrating Female Perspectives

Chiung Yao’s Suicide Farewell Letter: An English Translation

12-Year-Old Girl from Shandong Gets Infected with HPV: Viral Case Exposes Failures in Protecting Minors

Breaking the Taboo: China’s Sanitary Pad Controversy Sparks Demand for Change

Weibo Watch: Christmas in China Is Everywhere and Nowhere

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

Weibo Watch: China’s Online Feminism Is Everywhere

Story of Chinese Female MA Graduate Going Missing for 13 Years Sparks Online Storm

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight10 months ago

China Insight10 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music11 months ago

China Music11 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Insight12 months ago

China Insight12 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Digital9 months ago

China Digital9 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI