China Arts & Entertainment

The Success of China’s Hit Talk Show Qi Pa Shuo (U Can U Bibi)

The fourth season of China’s most popular online talk show Qi Pa Shuo is well underway. Using trendy design and funny sound effects, the show is a fresh debate competition where Chinese celebrities and showbiz newcomers discuss contemporary social and cultural issues. Qi Pa Shuo is a new type of entertainment show especially liked by China’s post-1980s and post-1990s generations for various reasons.

Published

8 years agoon

The fourth season of China’s most popular online talk show Qi Pa Shuo is well underway. Using trendy design and funny sound effects, the show is a fresh debate competition where Chinese celebrities and showbiz newcomers discuss contemporary social and cultural issues. Qi Pa Shuo is a new type of entertainment show especially liked by China’s post-1980s and post-1990s generations for various reasons.

Not a week goes by without Qi Pa Shuo (奇葩说), an online talk show competition created by iQiyi (爱奇艺), becoming the focus of discussion on Chinese social media sites. Although the show is already in its fourth season, it is now more popular than ever.

Qi Pa Shuo is a contemporary talk show concept that brings together a group of very diverse – often funny and extravagant – Chinese people to debate various topics and dilemma’s relating to, amongst others, love, marriage, family, career, and friendship.

Qi Pa Shuo was first aired in November of 2014 and still has staggering viewer ratings. The talk show is also big on Weibo, where its official page has over 1,1 million fans. Hashtags related to the show often become trending topics.

The panel of hosts/judges on Qi Pa Shuo, led by He Jiong, a key figure in China’s entertainment industry.

The huge success of the show lies in its marketing and concept as a purely online variety show that brings a somewhat sophisticated form of celebrity entertainment.

LET’S GET IT ONLINE: BOOMING ONLINE VIDEO MARKET

“Chinese tech giant Xiaomi paid a staggering 140 million rmb (±20 million US$) to be Qipashuo’s main sponsor.”

Qi Pa Shuo is an online talkshow, meaning that is created by Chinese online video portal iQiyi, where it is streamed twice a week. It is also online in the sense that the show interacts with topics that come from Chinese online social media.

Although China still has a flourishing television market, younger audiences now prefer online streaming to traditional TV channels. China has the largest online population in the world, and 88% of its internet users watch online videos, either on mobile or computer.

This percentage is higher when it comes to the younger online audiences, with 90.6% of the post-95s generation visiting video websites.

iQiyi (爱奇艺) is one of the biggest online video platforms of China. Sometimes referred to as “China’s Netflix”, iQiyi is an ad-supported video portal that offers high-definition licensed content to registered users. Apart from its online library with a myriad of movies from China and abroad, iQiyi also has its own production studio that produces films and other online content.

With the creation of Qi Pa Shuo, iQiyi has made a smart move. Since the majority of iQiyi users are born post-1980s, the program caters to the interests of that generation – not just in terms of content, but also in terms of style and fashion. The show already had 260 million views and then 300 million views in its first and second season.

The show is free to watch but is heavily sponsored; not a scene goes by without seeing product placement. Chinese tech giant Xiaomi reportedly paid a staggering 140 million rmb (±20 million US$) to be Qi Pa Shuo’s main sponsor for the fourth season. The Xiaomi brand name is visible in the show’s logo and practically everywhere else in the studio.

Qi Pa Shuo’s host He Jiong with branded content from sponsors on his desk.

Besides Xiaomi and Head & Shoulders shampoo, Chunzhen Yoghurt is also a prominent sponsor of the show, with packs of the products standing on all desks and tables.

As mentioned, the show is not just broadcasted online, it also interacts with online topics; the issues addressed in the show are selected from different online Chinese Quora-like Q&A forums such as Baidu Zhidao and Zhihu.

The most popular online topics related to love, lifestyle & career are selected to come on the show. In selecting the topics this way, the producers already know that they are of interest to a great number of netizens.

RIGHT TOPICS, RIGHT PEOPLE

“Is it a waste for women with a higher education to become a full-time housewife?”

Over the past few years, Qi Pa Shuo has seen a myriad of topics, including:

– “Is it okay to check your partner’s mobile phone?”

– “Should you have a stable career by 30 or should you chase your dreams?”

– “Can you get married without being in love?”

– “Is it a waste for women with a higher education to become a full-time housewife?”

– “Should you push your friends to return the money you borrowed them?”

– “Could you be a single mum?”

– “Should you help a school friend who is being bullied in fighting back or do you tell the teacher?”

– “Will you be happier with or without buying a house?”

Participants on the show, some being established names and others newcomers to Chinese showbiz, battle against each other in two teams in who is the best debater and who has the best Chinese speech skills. Celebrity judges or ‘mentors’ have to comment on the performance of the debaters, and debaters also have to try to convince the audience.

Qi Pa Shuo is called ‘Let’s Talk’ or ‘U Can You BiBi’ in English (the latter is a wordplay on Chinglish), but its Chinese title can be roughly translated as “Weirdo’s Say” or “Unusual Talk.” The term “Qi Pa” (奇葩) is often used to describe someone or something that is very odd or unusual. Participants on the show, both the newcomers and the well-known faces, are outspoken personalities with a special way of talking or unique fashion style.

By bringing together an eclectic group of big names and newbies, Qi Pa Shuo has the best of both worlds; it is a platform that attracts viewers because it features some of China’s most loved celebrities (host He Jiong, for example, has 83.8 million followers on Weibo), and it also keeps fans curious and attracted by introducing some new faces (Hu Tianya, Yan Rujing, Jiang Sida, etc.) – many of which have already become major celebrities themselves since the start of the show.

Presenter Shen Xia a.k.a. Dawang (1989) gained popularity after appearing on Qipashuo as a debater.

Although many of the topics discussed are frivolous and funny (“What would you do if you found an egg placed by an alien?”), the show has also seen some groundbreaking moments since it first aired.

Yan Rujing (1991) had her major breakthrough after becoming a Qi Pa Shuo debater.

In 2015, an episode on whether or not gays should come out to their parents moved many people to tears when celebrity mentor Kevin Tsai (Cai Kangyong/蔡康永) spoke openly about coming out as homosexual during his career as a Taiwanese TV host.

In an emotional speech, Tsai shared his difficult experiences of being openly gay in the showbusiness and said he hoped to convince people that “we’re not monsters.”

The show also made headlines in 2016 when internet celebrity Xi Ming a.k.a. Chao Xiaomi came on the show to talk about how it is to be gender fluid and not conform to a certain gender.

Chao Xiaomi came on the show in 2016 and discussed experiences as gender fluid individual (image via Time Out Beijing 2016).

Reactions on Chinese social media show just how alive the issues discussed in Qi Pa Shuo are, as topics adressed during the show often turn into heated discussions on Sina Weibo and other social media platforms, where netizens give their own viewpoint or discuss why they think their favorite debater is the best public speaker.

IMPROVING SPEECH SKILLS

“Communicating, convincing, negotiating, public speaking, debating – it is a basic skill we use in everyday life, but really mastering it is not easy.”

Recently, the success of Qi Pa Shuo is also often discussed in the Chinese media. According to an article by Rednet.com, one important reason why the talk show is such a hit is because young people in China are increasingly interested in debating and improving speech skills.

The Rednet article argues that Qi Pa Shuo is part of a broader talk show entertainment genre that is currently becoming more popular, showing that after online games and more superficial types of entertainment, there is now a new group of online audiences who want to see entertainment that is a bit more sophisticated and educational.

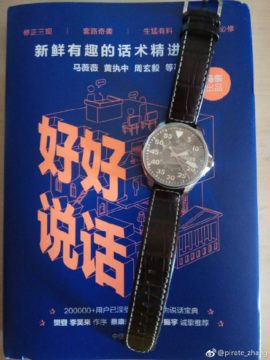

The growing interest in speech skills is also evident looking at the success of the podcasts and books on how to speak that sprang from the show, initiated by mentor Ma Dong and debater Ma Weiwei. Having good debating skills and general eloquence is seen as an asset for one’s career and social status.

Ma Weiwei (left) and Ma Dong.

“Because Qipashuo recommended this book, I simply just bought it to read it,” one netizen says on Weibo: “Who does not want to be able to speak like people such as Ma Dong or Ma Weiwei, so composed and self-assured. The book is pretty good, it teaches people how to speak well and how to say the right thing, it all makes sense. Communicating, convincing, negotiating, public speaking, debating – it is a basic skill we use in everyday life, but really mastering it is not easy.”

“How to Speak Well”, the book that have sprung from the Qi Pa Shuo programme.

On Weibo there are also vloggers like Baituola Junior (@拜托啦学妹) who take the topics as discussed in Qi Pa Shuo and make people on the streets discuss them.

These kinds of videos and trends show the rise of a generation that has a passion for speaking their mind and building strong arguments. Qi Pa Shuo further stimulates this drive by showing that anyone – girl or boy, young or old, gay or straight, goofy or trendy, celebrity or not – can be an effective and witty speaker if they put their mind to it.

Qi Pa Shuo is broadcasted every Friday and Saturday at 20.00 at iQiyi.com.

– By Manya Koetse

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

©2017 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Arts & Entertainment

How K-pop Fans and the 13-Year-Old Daughter of Baidu VP Sparked a Debate on Online Privacy

What began as K-pop fan outrage targeting a snarky commenter quickly escalated into a Baidu-linked scandal and a broader conversation about data privacy on Chinese social media.

Published

3 weeks agoon

March 26, 2025By

Ruixin Zhang

For an ordinary person with just a few followers, a Weibo account can sometimes be like a refuge from real life—almost like a private space on a public platform—where, along with millions of others, they can express dissatisfaction about daily annoyances or vent frustration about personal life situations.

But over recent years, even the most ordinary social media users could become victims of “opening the box” (开盒 kāihé)—the Chinese internet term for doxxing, meaning the deliberate leaking of personal information to expose or harass someone online.

A K-pop Fan-Led Online Witch Hunt

On March 12, a Chinese social media account focusing on K-pop content, Yuanqi Taopu Xuanshou (@元气桃浦选手), posted about Jang Wonyoung, a popular member of the Korean girl group IVE. As the South Korean singer and model attended Paris Fashion Week and then flew back the same day, the account suggested she was on a “crazy schedule.”

In the comment section, one female Weibo user nicknamed “Charihe” replied:

💬 “It’s a 12-hour flight and it’s not like she’s flying the plane herself. Isn’t sleeping in business class considered resting? Who says she can’t rest? What are you actually talking about by calling this a ‘crazy schedule’..”

Although the comment may have come across as a bit snarky, it was generally lighthearted and harmless. Yet unexpectedly, it brought disaster upon her.

That very evening, the woman nicknamed Charihe was bombarded with direct messages filled with insults from fans of Jang Wonyoung and IVE.

Ironically, Charihe’s profile showed she was anything but a hater of the pop star—her Weibo page included multiple posts praising Wonyoung’s beauty and charm. But that context was ignored by overzealous fans, who combed through her social media accounts looking for other posts to criticize, framing her as a terrible person.

After discovering through Charihe’s account that she was pregnant, Jang Wonyoung’s fans escalated their attacks by targeting her unborn child with insults.

The harassment did not stop there. Around midnight, fans doxxed Charihe, exposing her personal information, workplace, and the contact details of her family and friends. Her friends were flooded with messages, and some were even targeted at their workplaces.

Then, they tracked down Charihe’s husband’s WeChat account, sent him screenshots of her posts, and encouraged him to “physically punish” her.

The extremity of the online harassment finally drew backlash from netizens, who expressed concern for this ordinary pregnant woman’s situation:

💬 “Her entire life was exposed to people she never wanted to know about.”

💬 “Suffering this kind of attack during pregnancy is truly an undeserved disaster.”

Despite condemnation of the hate, some extreme self-proclaimed “fans” remained relentless in the online witch hunt against Charihe.

Baidu Takes a Hit After VP’s 13-Year-Old Daughter Is Exposed

One female fan, nicknamed “YourEyes” (@你的眼眸是世界上最小的湖泊), soon started doxxing commenters who had defended her. The speed and efficiency of these attacks left many stunned at just how easy it apparently is to trace social media users and doxx them.

Digging into old Weibo posts from the “YourEyes” account, people found she had repeatedly doxxed people on social media since last year, using various alt accounts.

She had previously also shared information claiming to study in Canada and boasted about her father’s monthly salary of 220,000 RMB (approx. $30.3K), along with a photo of a confirmation document.

Piecing together the clues, online sleuths finally identified her as the daughter of Xie Guangjun (谢广军), Vice President of Baidu.

From an online hate campaign against an innocent, snarky commenter, the case then became a headline in Chinese state media, and even made international headlines, after it was confirmed that the user “YourEyes”—who had been so quick to dig up others’ personal details—was in fact the 13-year-old daughter of Xie Guangjun, vice president at one of China’s biggest tech giants.

On March 17, Xie Guangjun posted the following apology to his WeChat Moments:

💬 “Recently, my 13-year-old daughter got into an online dispute. Losing control of her emotions, she published other people’s private information from overseas social platforms onto her own account. This led to her own personal information also getting exposed, triggering widespread negative discussion.

As her father, I failed to detect the problem in time and failed to guide her in how to properly handle the situation. I did not teach her the importance of respecting and protecting the privacy of others and of herself, for which I feel deep regret.

In response to this incident, I have communicated with my daughter and sternly criticized her actions. I hereby sincerely apologize to all friends affected.

As a minor, my daughter’s emotional and cognitive maturity is still developing. In a moment of impulsiveness, she made a wrong decision that hurt others and, at the same time, found herself caught in a storm of controversy that has subjected her to pressure and distress far beyond her age.

Here, I respectfully ask everyone to stop spreading related content and to give her the opportunity to correct her mistakes and grow.

Once again, I extend my apologies, and I sincerely thank everyone for your understanding and kindness.”

The public response to Xie’s apology has been largely negative. Many criticized the fact that it was posted privately on WeChat Moments rather than shared on a public platform like Weibo. Some dismissed the statement as an attempt to pacify Baidu shareholders and colleagues rather than take real accountability.

Netizens also pointed out that the apology avoided addressing the core issue of doxxing. Concerns were raised about whether Xie’s position at Baidu—and potential access to sensitive information—may have helped his daughter acquire the data she used to doxx others.

Adding fuel to the speculation were past conversations allegedly involving one of @YourEyes’ alt accounts. In one exchange, when asked “Who are you doxxing next?” she replied, “My parents provided the info,” with a friend adding, “The Baidu database can doxx your entire family.”

Following an internal investigation, Baidu’s head of security, Chen Yang (陈洋), stated on the company’s internal forum that Xie Guangjun’s daughter did not obtain data from Baidu but from “overseas sources.”

However, this clarification did little to reassure the public—and Baidu’s reputation has taken a hit. The company has faced prior scandals, most notably a the 2016 controversy over profiting from misleading medical advertisements.

Online Vulnerability

Beyond Baidu’s involvement, the incident reignited wider concerns about online privacy in China. “Even if it didn’t come from Baidu,” one user wrote, “the fact that a 13-year-old can access such personal information about strangers is terrifying.”

Using the hashtag “Reporter buys own confidential data” (#记者买到了自己的秘密#), Chinese media outlet Southern Metropolis Daily (@南方都市报) recently reported that China’s gray market for personal data has grown significantly. For just 300 RMB ($41), their journalist was able to purchase their own household registration data.

Further investigation uncovered underground networks that claim to cooperate with police, offering a “70-30 profit split” on data transactions.

These illegal data practices are not just connected to doxxing but also to widespread online fraud.

In response, some netizens have begun sharing guides on how to protect oneself from doxxing. For example, they recommend people disable phone number search on apps like WeChat and Alipay, hide their real name in settings, and avoid adding strangers, especially if they are active in fan communities.

Amid the chaos, K-pop fan wars continue to rage online. But some voices—such as influencer Jingzai (@一个特别虚荣的人)—have pointed out that the real issue isn’t fandom, but the deeper problem of data security.

💬 “You should question Baidu, question the telecom giants, question the government, and only then, fight over which fan group started this.”

As for ‘Charihe,’ whose comment sparked it all—her account is now gone. Her username has become a hashtag. For some, it’s still a target for online abuse. For others, it is a reminder of just how vulnerable every user is in a world where digital privacy is far from guaranteed.

By Ruixin Zhang

Independently covering digital China for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Memes & Viral

How Ne Zha 2’s Shen Gongbao Became Known as the Ultimate “Small-Town Swot”

Published

2 months agoon

March 1, 2025

PART OF THIS TEXT COMES FROM THE WEIBO WATCH PREMIUM NEWSLETTER

Over the past few weeks, the Chinese blockbuster Ne Zha 2 has been trending on Weibo every single day. The movie, loosely based on Chinese mythology and the Chinese canonical novel Investiture of the Gods (封神演义), has triggered all kinds of memes and discussions on Chinese social media (read more here and here).

One of the most beloved characters is the leopard demon Shen Gongbao (申公豹). While Shen Gongbao was a more typical villain in the first film, the narrative of Ne Zha 2 adds more nuance and complexity to his character. By exploring his struggles, the film makes him more relatable and sympathetic.

In the movie, Shen is portrayed as a sometimes sinister and tragic villain with humorous and likeable traits. He has a stutter, and a deep desire to earn recognition. Unlike many celestial figures in the film, Shen Gongbao was not born into privilege and never became immortal. As a demon who ascended to the divine court, he remains at the lower rungs of the hierarchy in Chinese mythology. He is a hardworking overachiever who perhaps turned into a villain due to being treated unfairly.

Many viewers resonate with him because, despite his diligence, he will never be like the gods and immortals around him. Many Chinese netizens suggest that Shen Gongbao represents the experience of many “small-town swots” (xiǎozhèn zuòtíjiā 小镇做题家) in China.

“Small-town swot” is a buzzword that has appeared on Chinese social media over the past few years. According to Baike, it first popped up on a Douban forum dedicated to discussing the struggles of students from China’s top universities. Although the term has been part of social media language since 2020, it has recently come back into the spotlight due to Shen Gongbao.

“Small-town swot” refers to students from rural areas and small towns in China who put in immense effort to secure a place at a top university and move to bigger cities. While they may excel academically, even ranking as top scorers, they often find they lack the same social advantages, connections, and networking opportunities as their urban peers.

The idea that they remain at a disadvantage despite working so hard leads to frustration and anxiety—it seems they will never truly escape their background. In a way, it reflects a deeper aspect of China’s rural-urban divide.

Some people on Weibo, like Chinese documentary director and blogger Bianren Guowei (@汴人郭威), try to translate Shen Gongbao’s legendary narrative to a modern Chinese immigrant situation, and imagine that in today’s China, he’d be the guy who trusts in his hard work and intelligence to get into a prestigious school, pass the TOEFL, obtain a green card, and then work in Silicon Valley or on Wall Street. Meanwhile, as a filial son and good brother, he’d save up his “celestial pills” (US dollars) to send home to his family.

Another popular blogger (@痴史) wrote:

“I just finished watching Ne Zha and my wife asked me, why do so many people sympathize with Shen Gongbao? I said, I’ll give you an example to make you understand. Shen Gongbao spent years painstakingly accumulating just six immortal pills (xiāndān 仙丹), while the celestial beings could have 9,000 in their hand just like that.

It’s like saving up money from scatch for years just to buy a gold bracelet, only to realize that the trash bins of the rich people are made of gold, and even the wires in their homes are made of gold. It’s like working tirelessly for years to save up 60,000 yuan ($8230), while someone else can effortlessly pull out 90 million ($12.3 million).In the Heavenly Palace, a single meal costs more than an ordinary person’s lifetime earnings.

Shen Gongbao seems to be his father’s pride, he’s a role model to his little brother, and he’s the hope of his entire village. Yet, despite all his diligence and effort, in the celestial realm, he’s nothing more than a marginal figure. Shen Gongbao is not a villain, he is just the epitome of all of us ordinary people. It is because he represents the state of most of us normal people, that he receives so much empathy.”

In the end, in the eyes of many, Shen Gongbao is the ultimate small-town swot. As a result, he has temporarily become China’s most beloved villain.

By Manya Koetse, with contributions by Wendy Huang

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Subscribe

Chinese New Nickname for Trump Mixes Fairy Tales with Tariff War

China Trending Week 15/16: Maozi & Meigui Fallout

China Reacts: 3 Trending Hashtags Shaping the Tariff War Narrative

No Quiet Qingming: From High-Tech Tomb-Sweeping to IShowSpeed & the Seven China Streams

From Trade Crisis to Patriotic Push: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Tariffs

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Beyond the Box Office: What’s Behind Ne Zha 2’s Success?

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

15 Years of Weibo: The Evolution of China’s Social Media Giant

Tuning Into the Year of the Snake

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

TikTok Refugees, Xiaohongshu, and the Letters from Li Hua

The ‘China-chic Girl’ Image and the Realities of China’s Competitive Food Delivery Market

US-Russia Rapprochement and “Saint Zelensky”: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Shake-Up

“Black Myth: Wukong”: From Gaming Screens to the CMG Spring Festival Gala?

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight11 months ago

China Insight11 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

-

China Arts & Entertainment11 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment11 months agoSinging Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Alex

May 25, 2017 at 4:36 am

Very interesting article! Is there somewhere I can watch this with English subtitles? My Chinese is not good enough to follow yet… I’m particularly interested in Chao Xiaomi’s episode about gender fluidity