Backgrounder

Suicide In China: The Story Behind the Declining Numbers

The story behind China’s suicide statistics.

Published

11 years agoon

The suicides of Chinese government officials, celebrities or office workers have consistently been making the headlines over the recent years. The latest statistics, however, shows that China has seen a dramatic drop in its suicide numbers, going from one of the world’s countries with highest suicide rates in the 1990s to a supposedly staggering 58% drop in the 2000s. What is the story behind these statistics?

Recently several international media, including The Economist, have reported a strong decline in China’s suicide rates over the past decade. These numbers are based on a 2014 study by Hong Kong University, estimating the average annual suicide rate for 2009-2011 at 9.8 per 100.000, a staggering drop since the 1990s, when China had estimated suicide rates of up to 32.9 per 100.000. The numbers are indeed astonishing; not only are they unique regarding their significant drop in suicide rate, they are also uncommon in the light of China’s economic growth. According to sociological views on suicide (based on the ideas of Durkheim), urbanization and modernization usually lead to a lack of interaction and cohesion within society, causing an increase in suicide rates. It has been the opposite for China, where a significant increase of economic development has gone hand in hand with a drop of suicide rates.

“Since 2000, the suicide rate in rural areas has grown steadily. It’s not too much to describe it as ‘extremely serious.'”

While media report about China’s lowering suicide number, there are also alarming reports about an increase of suicide amongst elders in China’s rural areas. Sociologist Liu Yanwu has stated that “the suicide rate in rural areas has grown steadily”, and that “it’s not too much to describe it as ‘extremely serious'” (Women of China 2014).

Are there less or more suicides in China? The reports are confusing. Former China Daily columnist Patrick Mattimore has called out to (western) media to question the conclusions of studies with vague research methods, warning that covering trending ‘China stories’ can actually give bad science the center stage (Mattimore 2014).

“Occasionally, the Western media fasten onto a “Chinese” story giving credence to bad science.”

A great part of the dispute on China’s suicide rates can be accounted to unrepresentative government data. The Chinese government has not officially published the PRC’s suicide numbers since 1999. The latest World Health Organization (WHO) data on suicides in China also dates back to 1999, when they reported an average rate of 13.9 per 100.000. This number is still not agreed on. In 2000, the former chief of China’s Ministry of Health already admitted that the average suicide rate from 1995-1999 was actually 22 per 100.000; a much greater number than originally reported to the WHO (Zhang 2014). In a 2002 report in Lancet, the number of suicides in the late 1990s was estimated at an annual 23 per 100.000 (Philips et al 2002, 835).

Blogger Zhang Debi stresses that in order to have clear statistics of a country’s suicide statistics, there must be an accurate system of mortality data – something that has been lacking in China. The 1999 ‘13.9’ rate was based on 21 provinces, 36 cities and 85 counties, composed of 57% of urban population. This has distorted the numbers, Zhang says, because it it has become widely acknowledged that China’s countryside suicide rate is higher than that of the urban areas. The number was later adjusted by the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) to 30.3, then the WHO readjusted it to 32.9 – more than twice the rate originally reported by China’s Ministry of Health.

No matter what report one believes, the suicide numbers in China have indeed dropped, although it might not be the staggering 58% drop. The benefits of China’s economic growth are believed to have caused the drop in suicides, especially amongst women in rural areas.

“The statistics make China unique when it comes down to suicide rates”

The statistics make China unique when it comes down to suicide in two ways: (1) it has a higher rate of suicide amongst women, whereas the rest of the world sees more men than women committing suicide, and (2) it has seen a drop in suicides during economic development, whereas it commonly is the other way around.

Suicide is the leading cause of death for women in rural areas in China. The most important factors are considered to be stress, possibly related to the strong patriarchal family structures, and the readily available pesticides: a widespread way of committing suicide in the countryside (WHO 2009). China’s economic development has created more opportunities for this group of women, who now find more freedom in moving to urbanized areas, getting educated and finding employment.

So can we expect the declining trend in suicide to continue in the years to come, and find a ‘happy ever after’? The Hong Kong University report suggests a more gloomy conclusion. Although the growing modernization and urbanization has done much good for countryside women, economic developments have a downside for rural older adults, who are suffering from more stress levels due to China’s rapid socioeconomic changes- causing a heightening suicide group for that group (Wang et al 2014, 929). Sociologist Liu has called the phenomenon a “sick suicide trend,” giving finances, bad health, and loneliness as the three major reasons for the suicide cases of old people in the countryside (Lu 2014). The recent developments suggest that suicide will remain a hot topic in ‘China stories’ in the years to come.

– by Manya Koetse

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

References

Lu Chen. 2014. “Elderly Suicide Rapidly Increasing in China’s Countryside.” Epoch Times (August 10) http://www.theepochtimes.com/n3/863657-elderly-suicide-rapidly-increasing-in-chinas-countryside/ (Accessed online August 14, 2014).

Mattirmore, Patrick. 2014. “Must question the conclusions of studies that offer vague research methods.” ContraCosta Time (August 9) http://www.contracostatimes.com/opinion/ci_26296468/guest-commentary-must-question-conclusions-studies-that-offer (Accessed online August 14, 2014).

Phillips, Michael R, Xianyun Li, Yanping Zhang. 2002. “Suicide rates in China, 1995–99.” Lancet 359: 835–40.

The Economist. 2014. “A dramatic decline in suicides – Back from the edge.” The Economist (June 28) http://www.economist.com/news/china/21605942-first-two-articles-chinas-suicide-rate-looks-effect-urbanisation-back (Accessed online August 14, 2014).

Wang, Chong-Wen, Cecilia L.W. Chan and Paul S.F. Yip. 2014. “Suicide Rates in China from 2002 to 2011: an update.” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 49(6): 929-941.

Women of China. 2014. “Wave of Suicides among China’s Rural Elderly Residents.” Women of China (August 12) http://www.womenofchina.cn/html/womenofchina/report/175054-1.htm (Accessed online August 14, 2014).

World Health Organization. 2009. Women and health: today’s evidence, tomorrow’s agenda . WHO Report (November) http://www.who.int/gender/documents/9789241563857/en/ (Accessed PDF online August 14, 2014).

Zhang Debi. 2014.“中国自杀率陡降”让人惊异 [The amazing drop in China’s suicide rate]” (In Chinese). 今日话题 [In Touch Today] (July 6) http://view.news.qq.com/original/intouchtoday/n2846.html (Accessed August 14, 2014).

Zhang Lie, Jing Jun et al 张 杰 景 军. 2011. “中国自杀率下降趋势的社会学分析 [Social Analysis of China’s Drop in Suicide Rate]”.中国社会科学 [China Social Sciences] (5).

Zhang, J.J. Ma, C. Jia, J. Sun, X. Guo, A. Xu, W. Li. 2010. “Economic growth and suicide rate changes: A case in China from 1982 to 2005.” European Psychiatry(25): 159–163.

Image: http://www.khmerload.com/news/919

(FYI: the woman in the picture was saved.)

Appreciate this article and want to help us pay for the upkeep costs of What’s on Weibo or donate a cup of (green) tea? You can do so here!

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

Backgrounder

“Oppenheimer” in China: Highlighting the Story of Qian Xuesen

Qian Xuesen is a renowned Chinese scientist whose life shares remarkable parallels with Oppenheimer’s.

Published

2 years agoon

September 16, 2023By

Zilan Qian

They shared the same campus, lived in the same era, and both played pivotal roles in shaping modern history while navigating the intricate interplay between science and politics. With the release of the “Oppenheimer” movie in China, the renowned Chinese scientist Qian Xuesen is being compared to the American J. Robert Oppenheimer.

In late August, the highly anticipated U.S. movie Oppenheimer finally premiered in China, shedding light on the life of the famous American theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer (1904-1967).

Besides igniting discussions about the life of this prominent scientist, the film has also reignited domestic media and public interest in Chinese scientists connected to Oppenheimer and nuclear physics.

There is one Chinese scientist whose life shares remarkable parallels with Oppenheimer’s. This is aerospace engineer and cyberneticist Qian Xuesen (钱学森, 1911-2009). Like Oppenheimer, he pursued his postgraduate studies overseas, taught at Caltech, and played a pivotal role during World War II for the US.

Qian Xuesen is so widely recognized in China that whenever I introduce myself there, I often clarify my last name by saying, “it’s the same Qian as Qian Xuesen’s,” to ensure that people get my name.

Some Chinese blogs recently compared the academic paths and scholarly contributions of the two scientists, while others highlighted the similarities in their political challenges, including the revocation of their security clearances.

The era of McCarthyism in the United States cast a shadow over Qian’s career, and, similar to Oppenheimer, he was branded as a “communist suspect.” Eventually, these political pressures forced him to return to China.

Although Qian’s return to China made his later life different from Oppenheimer’s, both scientists lived their lives navigating the complex dynamics between science and politics. Here, we provide a brief overview of the life and accomplishments of Qian Xuesen.

Departing: Going to America

Qian Xuesen (钱学森, also written as Hsue-Shen Tsien), often referred to as the “father of China’s missile and space program,” was born in Shanghai in 1911,1 a pivotal year marked by a historic revolution that brought an end to the imperial dynasty and gave rise to the Republic of China.

Much like Oppenheimer, who pursued further studies at Cambridge after completing his undergraduate education, Qian embarked on a journey to the United States following his bachelor’s studies at National Chiao Tung University (now Shanghai Jiao Tong University). He spent a year at Tsinghua University in preparation for his departure.

The year was 1935, during the eighth year of the Chinese Civil War and the fourth year of Japan’s invasion of China, setting the backdrop for his academic pursuits in a turbulent era.

Qian in his office at Caltech (image source).

One year after arriving in the U.S., Qian earned his master’s degree in aeronautical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Three years later, in 1939, the 27-year-old Qian Xuesen completed his PhD at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), the very institution where Oppenheimer had been welcomed in 1927. In 1943, Qian solidified his position in academia as an associate professor at Caltech. While at Caltech, Qian helped found NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

When World War II began, while Oppenheimer was overseeing the Manhattan Project’s efforts to assist the U.S. in developing the atomic bomb, Qian actively supported the U.S. government. He served on the U.S. government’s Scientific Advisory Board and attained the rank of lieutenant colonel.

The first meeting of the US Department of the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board in 1946. The predecessor, the Scientific Advisory Group, was founded in 1944 to evaluate the aeronautical programs and facilities of the Axis powers of World War II. Qian can be seen standing in the back, the second on the left (image source).

After the war, Qian went to teach at MIT and returned to Caltech as a full-time professor in 1949. During that same year, Mao Zedong proclaimed the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Just one year later, the newly-formed nation became involved in the Korean War, and China fought a bloody battle against the United States.

Red Scare: Being Labeled as a Communist

Robert Oppenheimer and Qian Xuesen both had an interest in Communism even prior to World War II, attending communist gatherings and showing sympathy towards the Communist cause.

Qian and Oppenheimer may have briefly met each other through their shared involvement in communist activities. During his time at Caltech, Qian secretly attended meetings with Frank Oppenheimer, the brother of J. Robert Oppenheimer (Monk 2013).

However, it was only after the war that their political leanings became a focal point for the FBI.

Just as the FBI accused Oppenheimer of being an agent of the Soviet Union, they quickly labeled Qian as a subversive communist, largely due to his Chinese heritage. While the government did not succeed in proving that Qian had communist ties with China during that period, they did ultimately succeed in portraying Qian as a communist affiliated with China a decade later.

During the transition from the 1940s to the 1950s, the Cold War was underway, and the anti-communist witch-hunts associated with the McCarthy era started to intensify (BBC 2020).

In 1950, the Korean War erupted, with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) joining North Korea in the conflict against South Korea, which received support from the United States. It was during this tumultuous period that the FBI officially accused Qian of communist sympathies in 1950, leading to the revocation of his security clearance despite objections from Qian’s colleagues. Four years later, in 1954, Robert Oppenheimer went through a similar process.

The 1950’s security hearing of Qian (second left). (Image source).

After losing his security clearance, Qian began to pack up, saying he wanted to visit his aging parents back home. Federal agents seized his luggage, which they claimed contained classified materials, and arrested him on suspicion of subversive activity. Although Qian denied any Communist leanings and rejected the accusation, he was detained by the government in California and spent the next five years under house arrest.

Five years later, in 1955, two years after the end of the Korean War, Qian was sent home to China as part of an apparent exchange for 11 American airmen who had been captured during the war. He told waiting reporters he “would never step foot in America again,” and he kept his promise (BBC 2020).

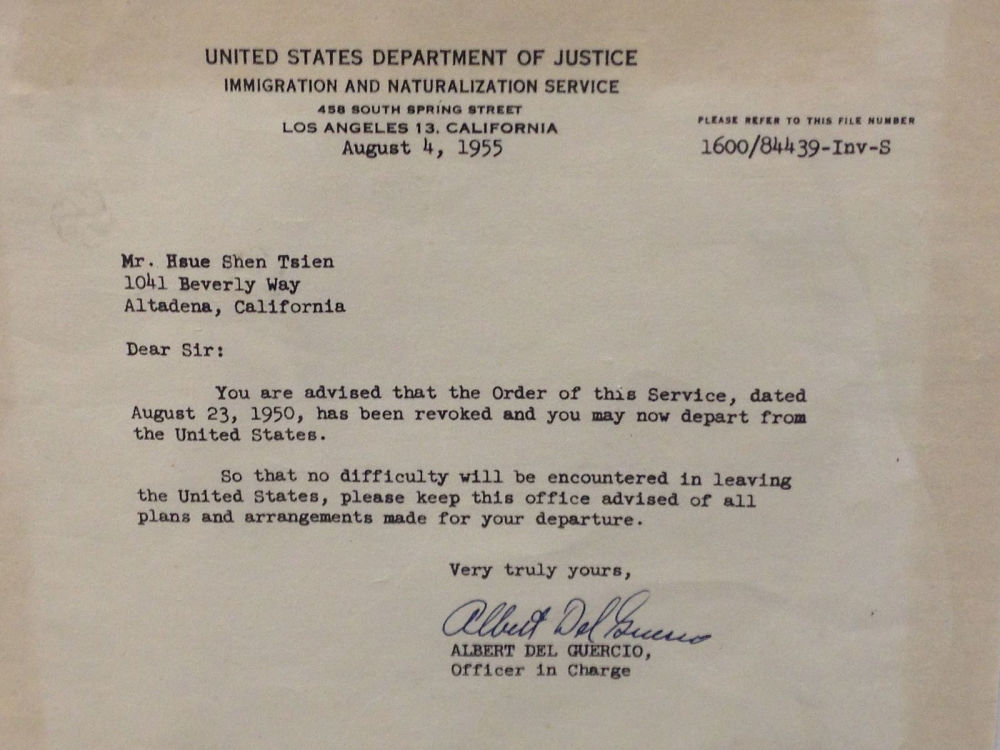

A letter from the US Immigration and Naturalization Service to Qian Xuesen, dated August 4, 1955, in which he was notified he was allowed to leave the US. The original copy is owned by Qian Xuesen Library of Shanghai Jiao Tong University, where the photo was taken. (Caption and image via wiki).

Dan Kimball, who was the Secretary of the US Navy at the time, expressed his regret about Qian’s departure, reportedly stating, “I’d rather shoot him dead than let him leave America. Wherever he goes, he equals five divisions.” He also stated: “It was the stupidest thing this country ever did. He was no more a communist than I was, and we forced him to go” (Perrett & Bradley, 2008).

Kimball may have foreseen the unfolding events accurately. After his return to China, Qian did indeed assume a pivotal role in enhancing China’s military capabilities, possibly surpassing the potency of five divisions. The missile programme that Qian helped develop in China resulted in weapons which were then fired back on America, including during the 1991 Gulf War (BBC 2020).

Returning: Becoming a National Hero

The China that Qian Xuesen had left behind was an entirely different China than the one he returned to. China, although having relatively few experts in the field, was embracing new possibilities and technologies related to rocketry and space exploration.

Within less than a month of his arrival, Qian was welcomed by the then Vice Prime Minister Chen Yi, and just four months later, he had the honor of meeting Chairman Mao himself.

Qian and Mao (image source).

In China, Qian began a remarkably successful career in rocket science, with great support from the state. He not only assumed leadership but also earned the distinguished title of the “father” of the Chinese missile program, instrumental in equipping China with Dongfeng ballistic missiles, Silkworm anti-ship missiles, and Long March space rockets.

Additionally, his efforts laid the foundation for China’s contemporary surveillance system.

By now, Qian has become somewhat of a folk hero. His tale of returning to China despite being thwarted by the U.S. government has become like a legendary narrative in China: driven by unwavering patriotism, he willingly abandoned his overseas success, surmounted formidable challenges, and dedicated himself to his motherland.

Throughout his lifetime, Qian received numerous state medals in recognition of his work, establishing him as a nationally celebrated intellectual. From 1989 to 2001, the state-launched public movement “Learn from Qian Xuesen” was promoted throughout the country, and by 2001, when Qian turned 90, the national praise for him was on a similar level as that for Deng Xiaoping in the decade prior (Wang 2011).

Qian Xuesen remains a celebrated figure. On September 3rd of this year, a new “Qian Xuesen School” was established in Wenzhou, Zhejiang Province, becoming the sixth high school bearing the scientist’s name since the founding of the first one only a year ago.

In 2017, the play “Qian Xuesen” was performed at Qian’s alma mater, Shanghai Jiaotong University. (Image source.)

Qian Xuesen’s legacy extends well beyond educational institutions. His name frequently appears in the media, including online articles, books, and other publications. There is the Qian Xuesen Library and a museum in Shanghai, containing over 70,000 artefacts related to him. Qian’s life story has also been the inspiration for a theater production and a 2012 movie titled Hsue-Shen Tsien (钱学森).2

Unanswered Questions

As is often the case when people are turned into heroes, some part of the stories are left behind while others are highlighted. This holds true for both Robert Oppenheimer and Qian Xuesen.

The Communist Party of China hailed Qian as a folk hero, aligning with their vision of a strong, patriotic nation. Many Chinese narratives avoid the debate over whether Qian’s return was linked to problems and accusations in the U.S., rather than genuine loyalty to his homeland.

In contrast, some international media have depicted Qian as a “political opportunist” who returned to China due to disillusionment with the U.S., also highlighting his criticism of “revisionist” colleagues during the Cultural Revolution and his denunciation of the 1989 student demonstrations.

Unlike the image of a resolute loyalist favored by the Chinese public, Qian’s political ideology was, in fact, not consistently aligned, and there were instances where he may have prioritized opportunity over loyalty at different stages of his life.

Qian also did not necessarily aspire to be a “flawless hero.” Upon returning to China, he declined all offers to have his biography written for him and refrained from sharing personal information with the media. Consequently, very little is known about his personal life, leaving many questions about the motivations driving him, and his true political inclinations.

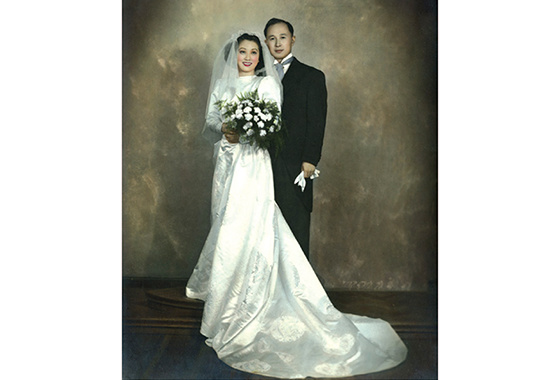

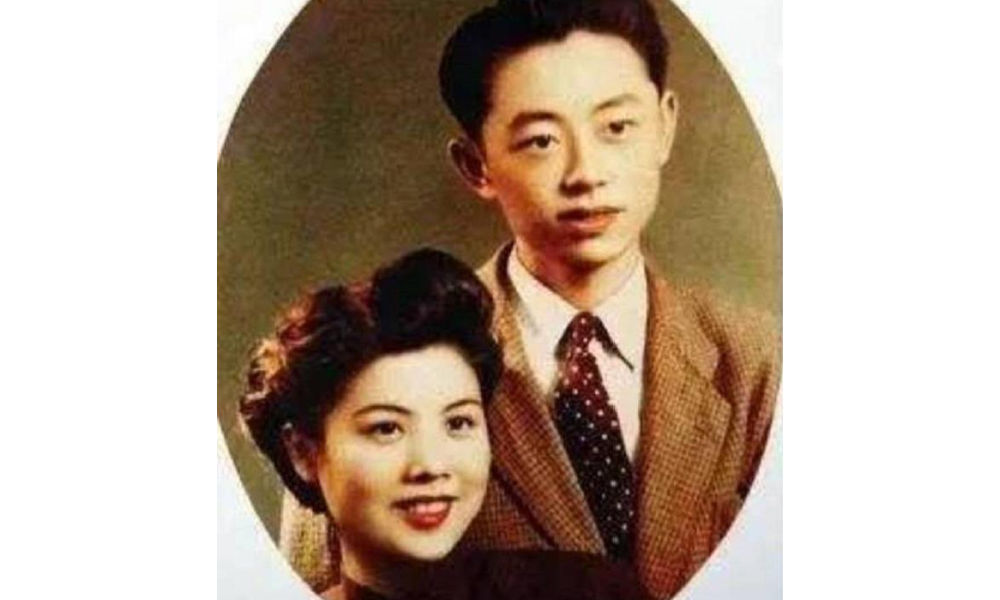

The marriage photo of Qian and Jiang. (Image source).

We do know that Qian’s wife, Jiang Ying (蒋英), had a remarkable background. She was of Chinese-Japanese mixed race and was the daughter of a prominent military strategist associated with Chiang Kai-shek. Jiang Ying was also an accomplished opera singer and later became a professor of music and opera at the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing.

Just as with Qian, there remain numerous unanswered questions surrounding Oppenheimer, including the extent of his communist sympathies and whether these sympathies indirectly assisted the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

Perhaps both scientists never imagined they would face these questions when they first decided to study physics. After all, they were scientists, not the heroes that some narratives portray them to be.

Also read:

■ Farewell to a Self-Taught Master: Remembering China’s Colorful, Bold, and Iconic Artist Huang Yongyu

■ “His Name Was Mao Anying”: Renewed Remembrance of Mao Zedong’s Son on Chinese Social Media

By Zilan Qian

Follow @whatsonweibo

1 Some sources claim that Qian was born in Hangzhou, while others say he was born in Shanghai with ancestral roots in Hangzhou.

2The Chinese character 钱 is typically romanized as “Qian” in Pinyin. However, “Tsien” is a romanization in Wu Chinese, which corresponds to the dialect spoken in the region where Qian Xuesen and his family have ancestral roots.

This article has been edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

References (other sources hyperlinked in text)

BBC. 2020. “Qian Xuesen: The man the US deported – who then helped China into space.” BBC.com, 27 October https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-54695598 [9.16.23].

Monk, Ray. 2013. Robert Oppenheimer: A Life inside the Center, First American Edition. New York: Doubleday.

Perrett, Bradley, and James R. Asker. 2008. “Person of the Year: Qian Xuesen.” Aviation Week and Space Technology 168 (1): 57-61.

Wang, Ning. 2011. “The Making of an Intellectual Hero: Chinese Narratives of Qian Xuesen.” The China Quarterly, 206, 352-371. doi:10.1017/S0305741011000300

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Backgrounder

Farewell to a Self-Taught Master: Remembering China’s Colorful, Bold, and Iconic Artist Huang Yongyu

Renowned Chinese artist and the creator of the ‘Blue Rabbit’ zodiac stamp Huang Yongyu has passed away at the age of 98. “I’m not afraid to die. If I’m dead, you may tickle me and see if I smile.”

Published

2 years agoon

June 15, 2023

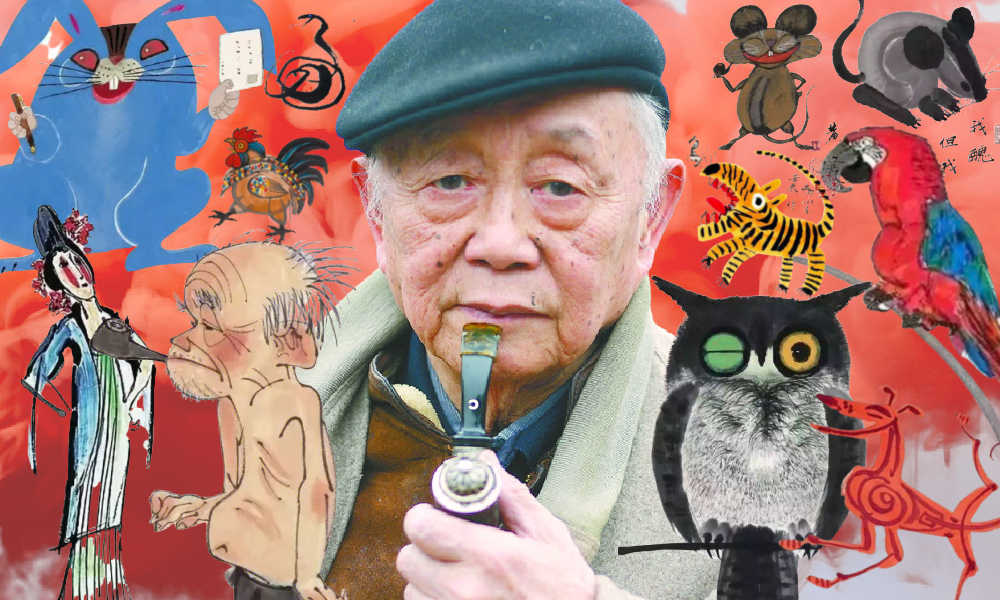

The famous Chinese painter, satirical poet, and cartoonist Huang Yongyu has passed away. Born in 1924, Huang endured war and hardship, yet never lost his zest for life. When his creativity was hindered and his work was suppressed during politically tumultuous times, he remained resilient and increased “the fun of living” by making his world more colorful.

He was a youthful optimist at old age, and will now be remembered as an immortal legend. The renowned Chinese painter and stamp designer Huang Yongyu (黄永玉) passed away on June 13 at the age of 98. His departure garnered significant attention on Chinese social media platforms this week.

On Weibo, the hashtag “Huang Yongyu Passed Away” (#黄永玉逝世#) received over 160 million views by Wednesday evening.

Huang was a member of the China National Academy of Painting (中国国家画院) as well as a Professor at the Central Academy of Fine Arts (中央美术学院).

Huang Yongyu is widely recognized in China for his notable contribution to stamp design, particularly for his iconic creation of the monkey stamp in 1980. Although he designed a second monkey stamp in 2016, the 1980 stamp holds significant historical importance as it marked the commencement of China Post’s annual tradition of releasing zodiac stamps, which have since become highly regarded and collectible items.

Huang’s famous money stamp that was issued by China Post in 1980.

The monkey stamp designed by Huang Yongyu has become a cherished collector’s item, even outside of China. On online marketplaces like eBay, individual stamps from this series are being sold for approximately $2000 these days.

Huang Yongyu’s latest most famous stamp was this year’s China Post zodiac stamp. The stamp, a blue rabbit with red eyes, caused some online commotion as many people thought it looked “horrific.”

Some thought the red-eyed blue rabbit looked like a rat. Others thought it looked “evil” or “monster-like.” There were also those who wondered if the blue rabbit looked so wild because it just caught Covid.

Huang’s (in)famous blue rabbit stamp.

Nevertheless, many people lined up at post offices for the stamps and they immediately sold out.

In light of the controversy, Huang Yongyu spoke about the stamps in a livestream in January of 2023. The 98-year-old artist claimed he had simply drawn the rabbit to spread joy and celebrate the new year, stating, “Painting a rabbit stamp is a happy thing. Everyone could draw my rabbit. It’s not like I’m the only one who can draw this.”

Huang’s response also went viral, with one Weibo hashtag dedicated to the topic receiving over 12 million views (#蓝兔邮票设计者直播回应争议#) at the time. Those defending Huang emphasized how it was precisely his playful, light, and unique approach to art that has made Huang’s work so famous.

A Self-Made Artist

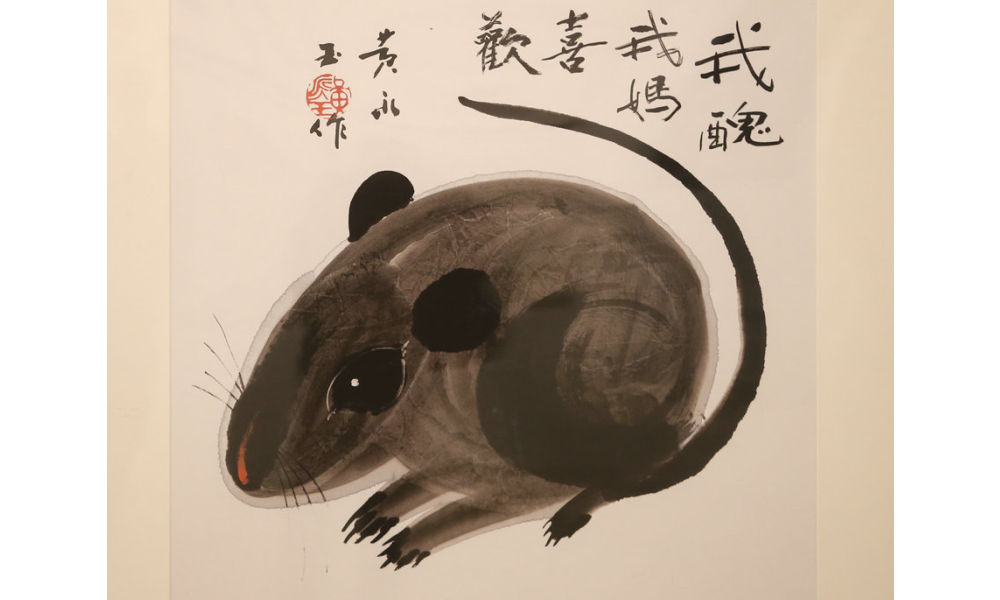

“I’m ugly, but my mum likes me”

‘Ugly Mouse’ by Huang Yongyu [Image via China Daily].

Huang Yongyu was born on August 9, 1924, in Hunan’s Chengde as a native of the Tujia ethnic group.

He was born into an extraordinary family. His grandfather, Huang Jingming (黄镜铭), worked for Xiong Xiling (熊希齡), who would become the Premier of the Republic of China. His first cousin and lifelong friend was the famous Chinese novelist Shen Congwen (沈从文). Huang’s father studied music and art and was good at drawing and playing the accordion. His mother graduated from the Second Provincial Normal School and was the first woman in her county to cut her hair short and wear a short skirt (CCTV).

Born in times of unrest and poverty, Huang never went to college and was sent away to live with relatives at the age of 13. His father would die shortly after, depriving him of a final goodbye. Huang started working in various places and regions, from porcelain workshops in Dehua to artisans’ spaces in Quanzhou. At the age of 16, Huang was already earning a living as a painter and woodcutter, showcasing his talents and setting the foundation for his future artistic pursuits.

When he was 22, Huang married his first girlfriend Zhang Meixi (张梅溪), a general’s daughter, with whom he shared a love for animals. He confessed his love for her when they both found themselves in a bomb shelter after an air-raid alarm.

Huang and Zhang Meixi [163.com]

In his twenties, Huang Yongyu emerged as a sought-after artist in Hong Kong, where he had relocated in 1948 to evade persecution for his left-wing activities. Despite achieving success there, he heeded Shen Congwen’s advice in 1953 and moved to Beijing. Accompanied by his wife and their 7-month-old child, Huang took on a teaching position at the esteemed Central Academy of Fine Arts (中央美术学院).

The couple raised all kinds of animals at their Beijing home, from dogs and owls to turkeys and sika deers, and even monkeys and bears (Baike).

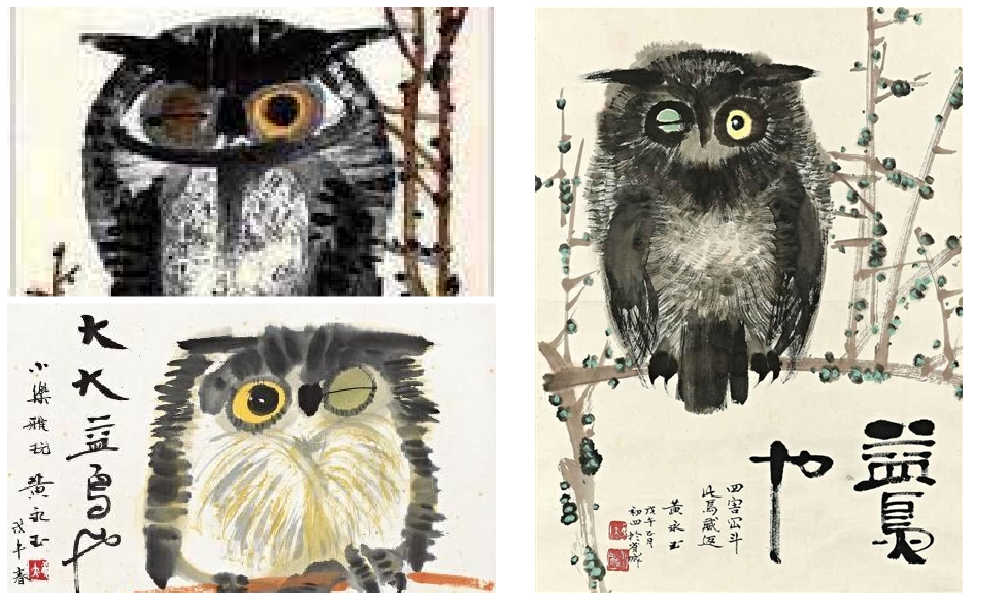

Throughout Huang’s career, animals played a significant role, not only reflecting his youthful spirit but also serving as vehicles for conveying satirical messages.

One recurring motif in his artwork was the incorporation of mice. In one of his famous works, a grey mouse is accompanied by the phrase ‘I’m ugly, but my mum likes me’ (‘我丑,但我妈喜欢’), reinforcing the notion that regardless of our outward appearance or circumstances, we remain beloved children in the eyes of our mothers.

As a teacher, Huang liked to keep his lessons open-minded and he, who refused to join the Party himself, stressed the importance of art over politics. He would hold “no shirt parties” in which his all-male studio students would paint in an atmosphere of openness and camaraderie during hot summer nights (Andrews 1994, 221; Hawks 2017, 99).

By 1962, creativity in the classroom was limited and there were far more restrictions to what could and could not be created, said, and taught.

Bright Colors in Dark Times

“Strengthen my resolve and increase the fun of living”

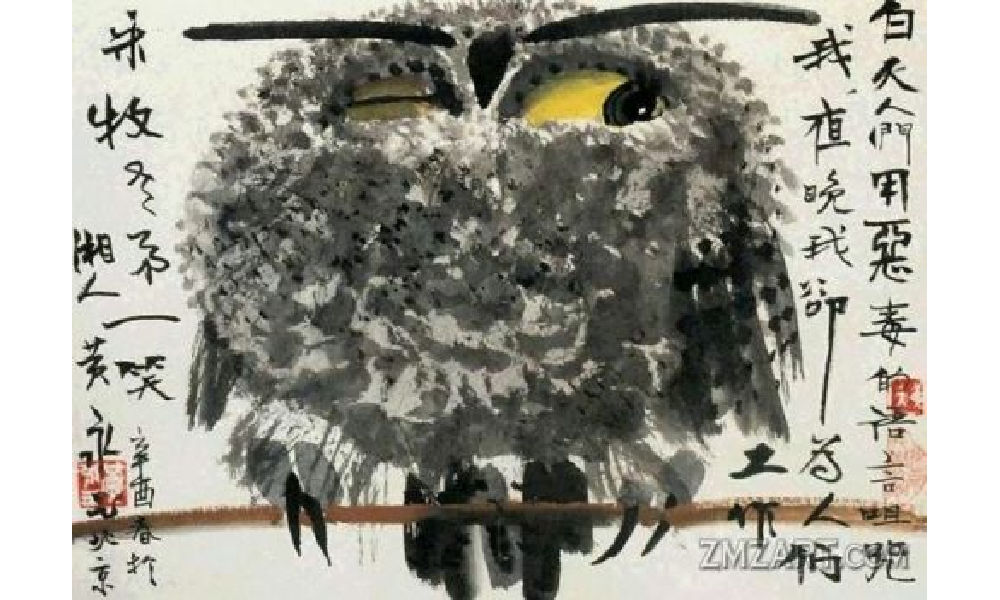

Huang Yongyu’s winking owl, 1973, via Wikiart.

In 1963, Huang was sent to the countryside as part of the “Four Cleanups” movement (四清运动, 1963-1966). Although Huang cooperated with the requirement to attend political meetings and do farm work, he distanced himself from attempts to reform his thinking. In his own time, and even during political meetings, he would continue to compose satirical and humorous pictures and captions centered around animals, which would later turn into his ‘A Can of Worms’ series (Hawks 2017, 99; see Morningsun.org).

Three years later, at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, many Chinese major artists, including Huang, were detained in makeshift jails called ‘niupeng‘ (牛棚), cowsheds. Huang’s work was declared to be counter-revolutionary, and he was denounced and severely beaten. Despite the difficult circumstances, Huang’s humor and kindness would remind his fellow artist prisoners of the joy of daily living (2017, 95-96).

After his release, Huang and his family were relocated to a cramped room on the outskirts of Beijing. The authorities, thinking they could thwart his artistic pursuits, provided him with a shed that had only one window, which faced a neighbor’s wall. However, this limitation didn’t deter Huang. Instead, he ingeniously utilized vibrant pigments that shone brightly even in the dimly lit space.

During this time, he also decided to make himself an “extra window” by creating an oil painting titled “Eternal Window” (永远的窗户). Huang later explained that the flower blossoms in the paining were also intended to “strengthen my resolve and increase the fun of living” (Hawks 2017, 4; 100-101).

Huang Yongyu’s Eternal Window [Baidu].

In 1973, during the peak of the Cultural Revolution, Huang painted his famous winking owl. The calligraphy next to the owl reads: “During the day people curse me with vile words, but at night I work for them” (“白天人们用恶毒的语言诅咒我,夜晚我为他们工作”) (Matthysen 2021, 165).

The painting was seen as a display of animosity towards the regime, and Huang got in trouble for it. Later on in his career, however, Huang would continue to paint owls. In 1977, when the Cultural Revolution had ended, Huang Yongyu painted other owls to ridicules his former critics (2021, 174).

According to art scholar Shelly Drake Hawks, Huang Yongyu employed animals in his artwork to satirize the realities of life under socialism. This approach can be loosely compared to George Orwell’s famous novel Animal Farm.

However, Huang’s artistic style, vibrant personal life, and boundary-pushing work ethic also draw parallels to Picasso. Like Picasso, Huang embraced a colorful life, adopted an innovative approach to art, and challenged artistic norms.

An Optimist Despite All Hardships

“Quickly come praise me, while I’m still alive”

Huang Yongyu will be remembered in China with love and affection for numerous reasons. Whether it is his distinctive artwork, his mischievous smile and trademark pipe, his unwavering determination to follow his own path despite the authorities’ expectations, or his enduring love for his wife of over 75 years, there are countless aspects to appreciate and admire about Huang.

One things that is certainly admirable is how he was able to maintain a youthful and joyful attitude after suffering many hardships and losing so many friends.

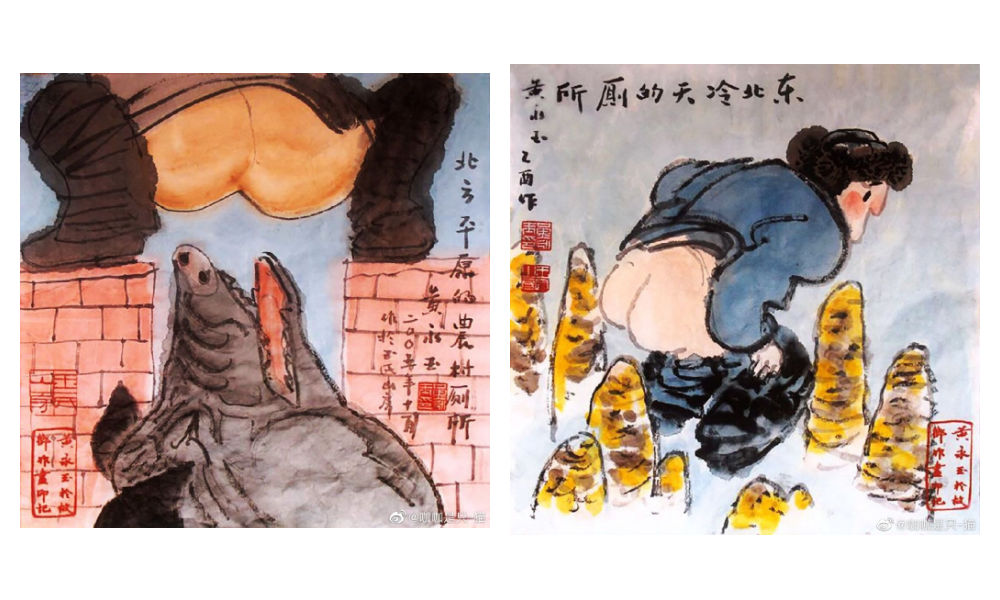

“An intriguing soul. Too wonderful to describe,” one Weibo commenter wrote about Huang, sharing pictures of Huang Yongyu’s “Scenes of Pooping” (出恭图) work.

Old age did not hold him back. At the age of 70, his paintings sold for millions. When he was in his eighties, he was featured on the cover of Esquire (时尚先生) magazine.

At the age of 82, he stirred controversy in Hong Kong with his “Adam and Eve” sculpture featuring male and female genitalia, leading to complaints from some viewers. When confronted with the backlash, Huang answered, “I just wanted to have a taste of being sued, and see how the government would react” (Ora Ora).

I'm guessing the 98-year-old Huang loved the controversy. When confronted with backlash for his sculpture featuring male and female genitalia in 2007 Hong Kong, Huang answered, "I just wanted to have a taste of being sued, and see how the government would react." pic.twitter.com/kG0MVVM4SN

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) June 15, 2023

In his nineties, he started driving a Ferrari. He owned mansions in his hometown in Hunan, in Beijing, in Hong Kong, and in Italy – all designed by himself (Chen 2019).

Huang kept working and creating until the end of his life. “It’s good to work diligently. Your work may be meaningful. Maybe it won’t be. Don’t insist on life being particularly meaningful. If it’s happy and interesting, then that’s great enough.”

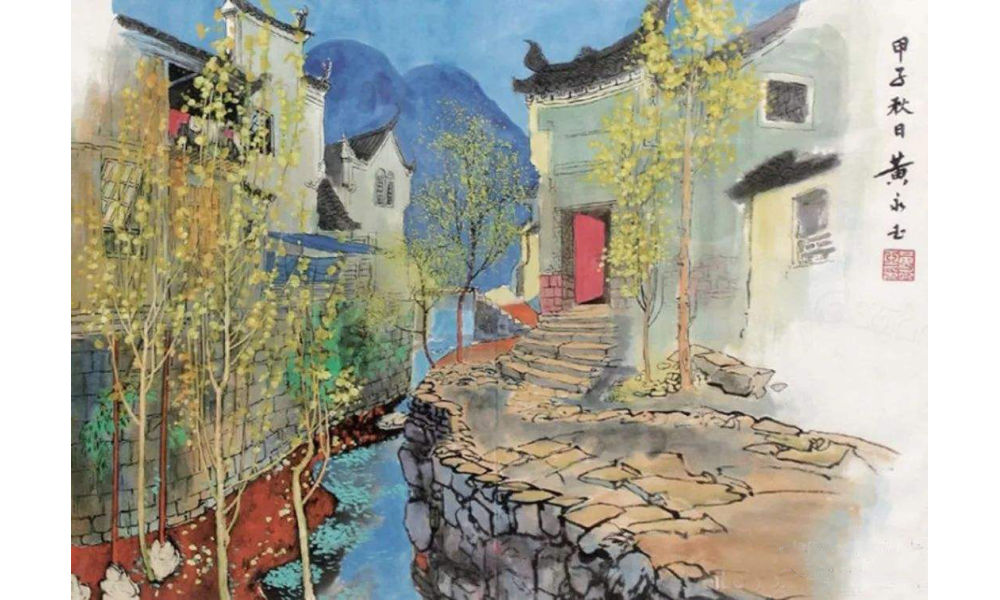

“Hometown Scenery” or rather “Hunan Scenery” (湘西风景) by Huang.

Huang did not dread the end of his life.

“My old friends have all died, I’m the only one left,” he said at the age of 95. He wrote his will early and decided he wanted a memorial service for himself before his final departure. “Quickly come praise me, while I’m still alive,” he said, envisioning himself reclining on a chair in the center of the room, “listening to how everyone applauds me” (CCTV, Sohu).

He stated: “I don’t fear death at all. I always joke that when I die, you should tickle me first and see if I’ll smile” (“对死我是一点也不畏惧,我开玩笑,我等死了之后先胳肢我一下,看我笑不笑”).

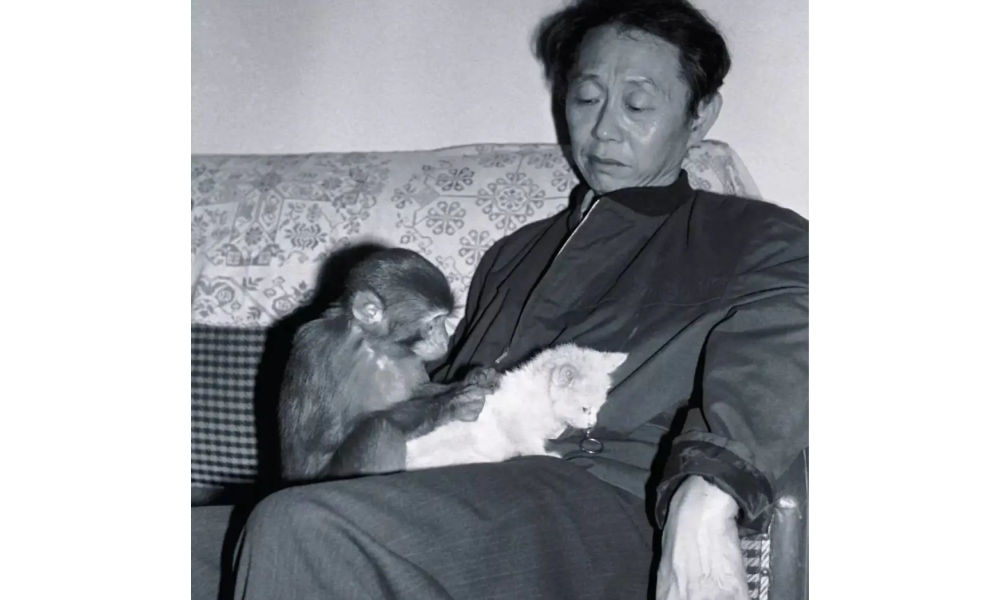

Huang with Yiwo (伊喔), the original model for the monkey stamp [Shanghai Observer].

Huang also was not sentimental about what should happen to his ashes. In a 2019 article in Guangming Daily, it was revealed that he suggested to his wife the idea of pouring his ashes into the toilet and flushing them away with the water.

However, his wife playfully retorted, saying, “No, that won’t do. Your life has been too challenging; you would clog the toilet.”

To this, Huang responded, “Then wrap my ashes into dumplings and let everyone [at the funeral] eat them, so you can tell them, ‘You’ve consumed Huang Yongyu’s ashes!'”

But she also opposed of that idea, saying that they would vomit and curse him forever.

Nevertheless, his wife expressed opposition to this idea, citing concerns that it would cause people to vomit and curse him indefinitely.

In response, Huang declared, “Then let’s forget about my ashes. If you miss me after I’m gone, just look up at the sky and the clouds.” Eventually, his wife would pass away before him, in 2020, at the age of 98, having spent 77 years together with Huang.

Huang will surely be missed. Not just by the loved ones he leaves behind, but also by millions of his fans and admirers in China and beyond.

“We will cherish your memory, Mr. Huang,” one Weibo blogger wrote. Others honor Huang by sharing some of his famous quotes, such as, “Sincerity is more important than skill, which is why birds will always sing better than humans” (“真挚比技巧重要,所以鸟总比人唱得好”).

Among thousands of other comments, another social media user bid farewell to Huang Yongyu: “Our fascinating Master has transcended. He is now a fascinating soul. We will fondly remember you.”

By Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

References

Andrews, Julia Frances. 1994. Painters and Politics in the People’s Republic of China, 1949-1979. Berkley: University of California Press.

Baike. “Huang Yongyu 黄永玉.” Baidu Baike https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E9%BB%84%E6%B0%B8%E7%8E%89/1501951 [June 14, 2023].

CCTV. 2023. “Why Everyone Loves Huang Yongyu [为什么人人都爱黄永玉].” WeChat 央视网 June 14.

Chen Hongbiao 陈洪标. 2019. “Most Spicy Artist: Featured in a Magazine at 80, Flirting with Lin Qingxia at 91, Playing with Cars at 95, Wants Memorial Service While Still Alive [最骚画家:80岁上杂志,91岁撩林青霞,95岁玩车,活着想开追悼会].” Sohu/Guangming Daily March 16: https://www.sohu.com/a/301686701_819105 [June 15, 2023].

Hawks, Shelley Drake. 2017. The Art of Resistance Painting by Candlelight in Mao’s China. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Matthysen, Mieke. 2021. Ignorance is Bliss: The Chinese Art of Not Knowing. Palgrave Macmillan.

Ora Ora. “HUANG YONGYU 黃永玉.” Ora Ora https://www.ora-ora.com/artists/103-huang-yongyu/ [June 15, 2023].

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

How K-pop Fans and the 13-Year-Old Daughter of Baidu VP Sparked a Debate on Online Privacy

Squat or Sit? China’s Great Toilet Debate and the Problem of Footprints on the Seat

Weibo Watch: The Great Squat vs Sitting Toilet Debate in China🧻

Chinese Netizens Turn to Tim Cook Over Battery Factory’s Illegal Overtime

Our Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Beyond the Box Office: What’s Behind Ne Zha 2’s Success?

Weibo Watch: Christmas in China Is Everywhere and Nowhere

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

15 Years of Weibo: The Evolution of China’s Social Media Giant

Tuning Into the Year of the Snake

The ‘China-chic Girl’ Image and the Realities of China’s Competitive Food Delivery Market

TikTok Refugees, Xiaohongshu, and the Letters from Li Hua

“Black Myth: Wukong”: From Gaming Screens to the CMG Spring Festival Gala?

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight11 months ago

China Insight11 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music12 months ago

China Music12 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

-

China Arts & Entertainment11 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment11 months agoSinging Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments