China Memes & Viral

The ‘Cycling to Kaifeng’ Trend: How It Started, How It’s Going

The Kaifeng cycling craze revealed more than just the adventurous spirit of Chinese students.

Published

4 months agoon

PREMIUM CONTENT

From city marketing to the spirit of China’s new generation, there are many themes behind the recent Zhengzhou trend of thousands of students cycling to Kaifeng overnight.

The term ‘yè qí‘ (夜骑), meaning “night ride,” has recently become a buzzword on Chinese social media. Large groups of students from various schools and universities in Zhengzhou, the capital of Henan province with a population of over 12 million, have been cycling en masse on shared bikes to Kaifeng, a neighboring historic city of around 5 million residents. These journeys often begin in the evenings or around midnight.

Across multiple platforms, videos of swarms of cyclists heading to Kaifeng have gone viral. The footage is striking, capturing streams of students embarking on the 40-mile nighttime journey, some waving Chinese flags, filming on their phones, singing together, and clearly having a great time.

According to some reports, approximately 100,000 or even 200,000 students have participated in these rides, drawing significant media attention both in China and internationally—especially after authorities began imposing restrictions on the so-called ‘Night Riding Army.’

HOW IT STARTED

The true origins of this story seem a bit murky.

The first Chinese news reports and blogs about students cycling to Kaifeng began surfacing around November 2-3 this year, coinciding with the first large-scale group rides from Zhengzhou to Kaifeng. The trend seemed to emerge out of nowhere.

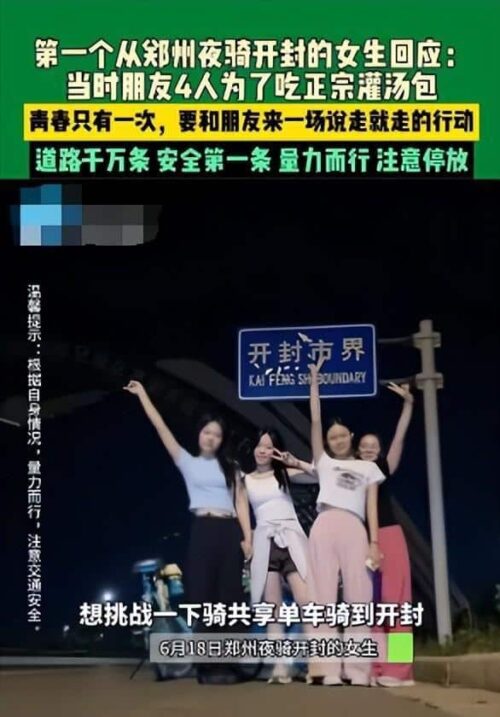

On November 3, numerous Chinese media outlets provided an explanation for the phenomenon. According to these reports, on June 18, 2024, four female friends allegedly decided, at 7 PM, to embark on a 40-mile journey from Zhengzhou to Kaifeng to try out the city’s renowned soup dumplings. It took them around five hours to ride there, and, when they shared their adventure online, they used the slogan: “Youth only comes once” (青春只有一次).

These four girls allegedly started the Kaifeng night ride trend in June of 2024 (The Paper).

Their posts were said to have inspired hundreds of other students to follow suit, organizing night rides in groups with the trend peaking during the first two weekends of November. This narrative of an organic trend of night riding to Kaifeng for dumplings was picked up by Western media outlets, including reports from the BBC and The Guardian.

Earlier in summer, some Henan media indeed reported about four girls doing a night ride to Kaifeng. This was followed by another video by a Douyin user (@去你的岛), dated June 23, documenting a ride from Zhengzhou to Kaifeng for breakfast. That video was later turned into a small news item (dated June 29, but showing footage of the June 23 ride). Aside from an October 6 video by another Douyin user (@小木同学) imitating the June 23 group by cycling to Kaifeng with friends, however, there is a notable lack of videos indicating a widespread cycling-to-Kaifeng trend before the large-scale group rides of November 2-3. Moreover, the original posts by the four girls are nowhere to be found.

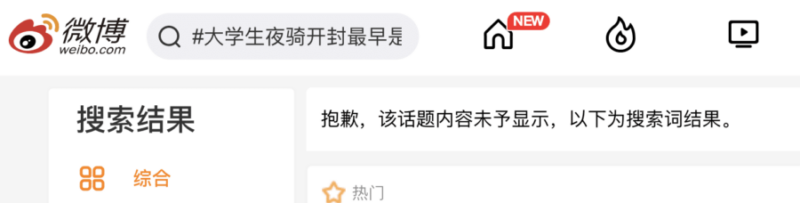

This raises questions: How did the story of the four girls gain traction without leaving a significant digital footprint? Was the Zhengzhou-to-Kaifeng cycling trend a truly organic movement, or could it have been more orchestrated? Curiously, the Weibo hashtag “How did the college students’ night ride to Kaifeng initially start?” (#大学生夜骑开封最早是怎么开始的#), which had been used by multiple bloggers, was also taken offline at the time of writing.

Screenshot of Weibo hashtag not being displayed.

The origins of the trend are particularly relevant as Chinese cities fiercely compete to become the next social media sensation. Since Zibo’s viral success, third- and second-tier cities across China have been striving to replicate its fame. While it’s ideal to become the next travel hit organically, cities often benefit from promoting local specialities and hyping up meme-worthy moments. Cities like Tianshui in Gansu and Harbin have enjoyed their moments in 2024, propelled by memes and viral content.

Kaifeng had already launched initiatives to boost tourism before the cycling trend. In March, a special shuttle service from Zhengzhou to Kaifeng was introduced to encourage day trips. In April, the city debuted its “Wang Po Matchmaking” show at Wansui Mountain Martial Arts City to attract tourists.

Tourist offices nationwide have become increasingly savvy in using social media for city marketing. Given the absence of a substantial social media trend from June to November, it seems plausible that the cycling phenomenon was a coordinated marketing effort. It likely began with a large group ride in early November, which sparked student interest, and snowballed. Kaifeng capitalized on the social media buzz starting November 2, but the scale of the phenomenon probably far exceeded what anyone had expected.

A CRAZY RIDE

As the ‘Zhengzhou to Kaifeng Night Ride’ was reported by local media and hit social media charts during the first weekend of November, it didn’t take long for students to catch on and join the ride. By the second weekend of November, Zhengkai Avenue, the main road from Zhengzhou to Kaifeng, was buzzing with activity, packed with thousands of university students participating in the night ride. Waving national flags, singing songs – including the national anthem -, taking group pictures, the moment was all that mattered.

Night riding while waving the national flag.

While some foreign media speculated that the movement carried political undertones, citing at least one flag on the road advocating for the reunification of Taiwan with the motherland, it was likely more about patriotic youth waving non-controversial flags while channeling some nationalistic energy.

It was about “passion”—an English word that became synonymous with the nightly bike ride. It wasn’t about the soup dumplings or the exercise; it was about joy, freedom, and the pure, youthful energy of passion—an important theme for China’s Generation Z, the post-95 and post-00 generations, who often feel pushed and sometimes even paralyzed by the intense social pressures they face.

Night riders posing with a poster saying : You need passion in your life (source).

The trend was supported (or facilitated?) by Kaifeng authorities. On November 3, they set up shared bike stations along Zhengkai Avenue to manage the influx of cyclists. Police provided guidance at the scene and ensured safety throughout the night. Kaifeng’s Tourism Bureau issued a “cycling safety advisory” via its official WeChat account, encouraging visitors to adhere to traffic rules, travel sustainably, avoid peak times, and “enjoy the seasonal beauty of Kaifeng with a positive attitude.”

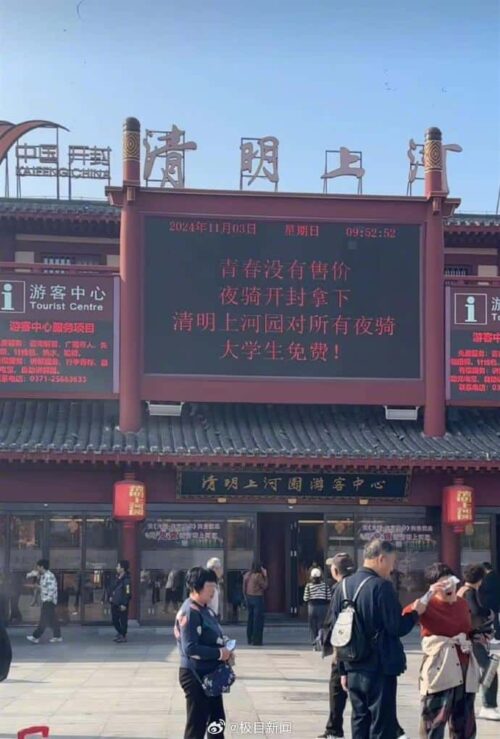

Starting on November 3, Kaifeng’s main tourist attractions, such as Millennium City Park, Wansui Mountain, and Daxiangguo Temple were specially opened to the ‘night riders’ in the middle of the night, even offering them free annual tourism passes (#开封多个景点为夜骑大学生免费#). At this time, the slogan “Youth is priceless, seize the night ride to Kaifeng” (“青春没有售价,夜骑开封拿下”) was actively promoted at Kaifeng tourist spots and in the media.

Historical cultural theme park Millennium City Park in Kaifeng on November 3, promoting free access to night riders and the slogan “Youth is priceless, seize the night ride to Kaifeng.”

The shuttle bus taking students back to Zhengzhou was provided for free.

On social apps like Xiaohongshu, students shared various ‘strategy guides’ for the best way to navigate the nightly ride to Kaifeng, including tips such as:

- Choose a comfortable shared bike and avoid unlocking it along the way. With a bike like HelloBike, the journey will only cost 19.5 RMB ($2.70). Starting from Zhengzhou Sports Center Station, head north on Jinshui Road and cycle east in a straight line to Kaifeng. The trip should take about 4 hours.

- From Zhengzhou University to Kaifeng Gulou, the total distance is 79.4 km, with an estimated travel time of 6 hours and 38 minutes. Including breaks and meal stops, the journey could take at least 8 hours.

- Bring a small flag for photo opportunities.

- Upon arrival, visit the Haidilao hotpot restaurant, where they provide blankets and snacks.

- Must-try local dishes: soup dumplings, egg casserole, and deep-fried dough with soy milk.

GOING DOWNHILL

During the weekend of November 8-9, numerous videos emerged showing thousands of students cycling from Zhengzhou to Kaifeng, revealing chaotic scenes (link, link). Some estimates suggested that over 30,000 students had arrived in Kaifeng in a single night.

The trend had a significant impact, raising several concerns. Safety issues loomed large as the sheer number of bicycles on the road created risks, especially given that many participants lacked experience with long-distance cycling. Traffic congestion reached such levels that some cars became trapped amid the cycling groups.

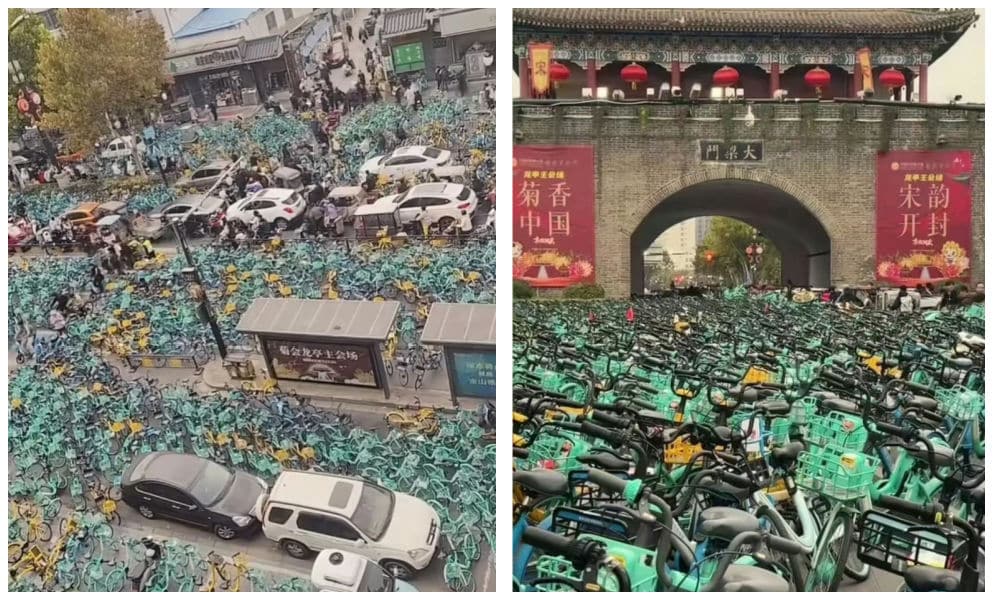

The shared bike system also faced severe challenges. While students eagerly undertook the 4-5 hour downhill journey to Kaifeng, they were unwilling to make the uphill return to Zhengzhou. This resulted in thousands of bikes being abandoned in Kaifeng or along the route, requiring retrieval by the bike companies.

Beyond logistical strain on the bike-sharing system, the abandoned bikes caused significant disruptions in Kaifeng, with entire roads blocked. In Zhengzhou, locals complained about a lack of available bikes for their commutes.

Shared bike chaos in Kaifeng.

While some praised the students’ adventurous spirit, others grew increasingly frustrated with the mounting problems.

By the afternoon of November 9, the official narrative shifted.

Initially, Chinese media celebrated the trend, but reports soon focused on its downsides. One widely shared story featured a 34-year-old man who had joined the ride with his daughter. Unaccustomed to cycling, he became exhausted after only 12-13 kilometers (about 8 miles) (#郑州34岁男子跟风夜骑开封后住院#). He was later hospitalized and diagnosed with hypokalemia (low potassium levels). The message? “Don’t blindly follow the trend.”

Authorities quickly stepped in to stop the night rides. Traffic police in Zhengzhou and Kaifeng issued a joint announcement banning the use of bike lanes on Zhengkai Avenue from 16:00 on November 9 to 12:00 on November 10.

Three major shared bike companies—Meituan, HelloBike, and Qingju—released statements reminding users that their bikes were not intended for cross-city travel. Bikes taken beyond designated zones would automatically lock and incur ‘relocation fees.’

Several universities implemented strict measures, ordering students back to campus and enforcing lockdowns. By Sunday night, some students took to Weibo to report that they were still not allowed to leave their campuses.

THE ROAD AHEAD

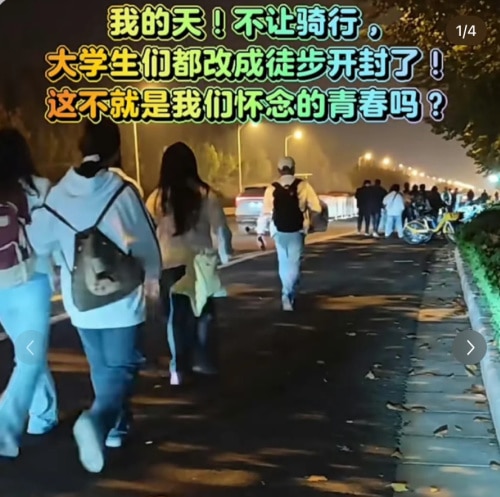

Despite the official crackdown on night rides to Kaifeng, some Zhengzhou students have now shifted to walking the entire route, a journey that can take up to 11 hours—equating to 70,000-100,000 steps on a smartwatch pedometer.

Unable to cycle, groups of students decided to walk to Kaifeng.

The crackdown on the nightly cycling craze has also prompted some reflection.

While many netizens praise the students for “truly embodying youth and vitality,” others see a deeper significance in the trend.

On Weibo, author Xu Kaizhen (许开祯) offers his perspective on what the Kaifeng phenomenon reveals about Chinese youth today. He writes:

“On the surface, the Kaifeng craze appears to be the latest trend in cultural tourism. But at its core, it has nothing to do with tourism. What is it really about? It’s about young people, about youth. And it’s not about youthful rebellion or hormones—modern youth have moved beyond that. It’s about escape. A collective, grand escape. An escape from a mediocre era, a mediocre life, and even a mediocre background. Every young person who joined the night ride was driven by a need to escape. Dissatisfied with reality yet powerless to change it, they turned to this collective unconscious act of performance art.”

Despite the criticism, it seems many hold a soft spot for China’s youth, understanding the challenges they face. As one popular comment puts it: “I dearly love this generation of Chinese youth. Their daytime has been drained by the previous generation, leaving only the night for them to carve out some space to unwind. ‘Escape’ describes it perfectly.”

For now, it seems the Kaifeng trend isn’t over. What began as an innocent, fun-loving initiative has turned into a mass mobilization that raises questions about hyped-up tourism, city marketing, and, most importantly, the boundless energy of China’s new generation. While the phenomenon has left many puzzled, some argue it’s crucial to grasp the youth’s yearning for these kinds of adventures.

As Xu Kaizhen concluded: “Perhaps by understanding this night ride, we can truly understand this generation. No—perhaps we can begin to understand the coming era.”

See our X thread with videos on this trend.

By Manya Koetse, with contributions by Miranda Barnes

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

You may like

China Digital

Chinese Netizens Turn to Tim Cook Over Battery Factory’s Illegal Overtime

Is turning to Western suppliers an effective way for workers to pressure domestic companies into complying with labor laws?

Published

5 days agoon

March 20, 2025

We include this content in the Weibo Watch newsletter. Subscribe to get it in your inbox 📩

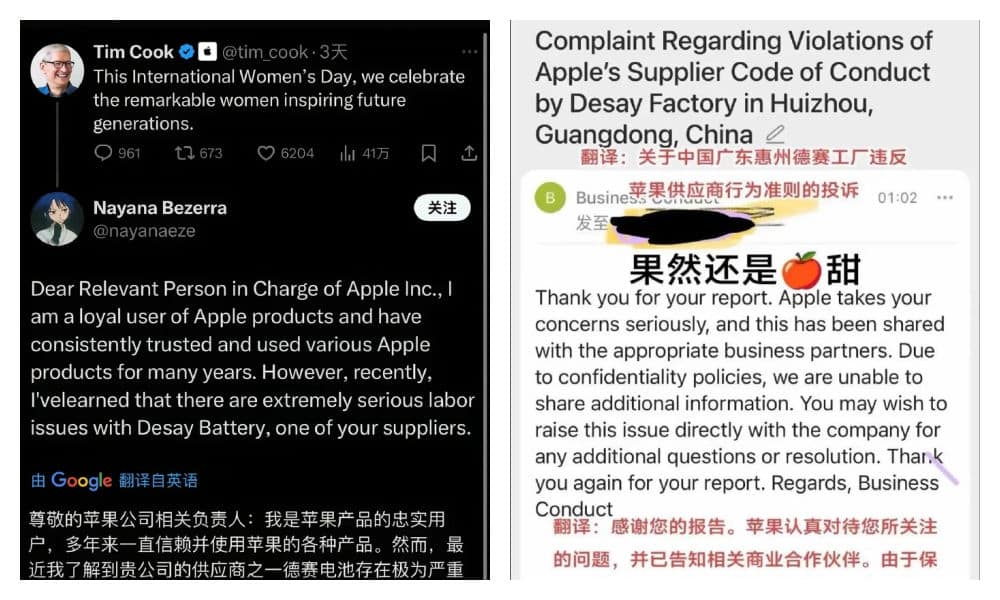

Recently, Chinese netizens have started reaching out to Apple and its CEO Tim Cook in order to put pressure on a state-owned battery factory accused of violating labor laws.

The controversy involves the Huizhou factory of Desay Battery (德赛电池), known for producing lithium batteries for the high-end smartphone market, including Apple and Samsung. The factory caught netizens’ attention after a worker exposed in a video that his superiors were deducting three days of wages because he worked an 8-hour shift instead of the company’s “mandatory 10-hour on-duty.” Compulsory overtime violates China’s labor laws.

In response, the worker and other netizens started to let Apple know about the situation through email and social media, trying to put pressure on the factory by highlighting its position in the Apple supply chain. In at least one instance, Apple confirmed receipt of the complaint. (Meanwhile, on Tim Cook’s official Weibo account, the comment section underneath his most recent post is clearly being censored.)

Screenshot of replies on X underneath a post by Tim Cook on International Women’s Day.

The factory, however, has denied the allegations, , claiming that the video creator was spreading untruths and that they had reported him to authorities. His content has since also been removed. A staff member at Desay Battery maintained that they adhere to the 8-hour workday and appropriately compensate workers for overtime.

At the same time, Desay Battery issued an official statement, admitting to “management oversights regarding employee rights protection” (“保障员工权益的管理上存在疏漏”) and promising to do better in safeguarding employee rights.

One NetEase account (大风文字) suggested that for Chinese workers to effectively expose labor violations, reporting them to Western suppliers or EU regulators is an effective way to force domestic companies to respect labor laws.

Another commentary channel (上峰视点) was less optimistic about the effectiveness, arguing that companies like Apple would be quick to drop suppliers over product quality issues but more willing to turn a blind eye to labor violations—since cheap labor remains a key competitive advantage in Chinese manufacturing.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Media

Revisiting China’s Most Viral Resignation Letter: “The World Is So Big, I Want to Go and See It”

The woman behind the famous resignation note, ‘I want to see the world,’ ended up traveling in China before going back home.

Published

6 days agoon

March 19, 2025

We include this content in the Weibo Watch newsletter. Subscribe to get it in your inbox 📩

“The world is so big, I want to go out and see it” (Shìjiè nàme dà, wǒ xiǎng qù kànkan “世界那么大,我想去看看”).

This ten-character sentence became part of China’s collective social media memory after a teacher’s resignation note went viral in 2015. Now, a decade later, the phrase has gone viral once again.

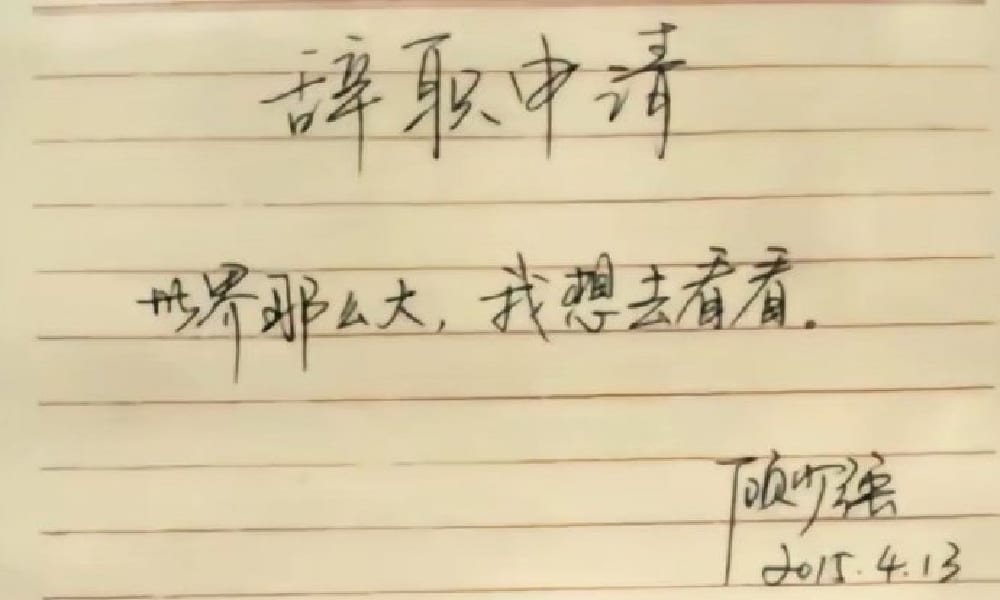

In April 2015, the phrase caused a huge buzz on China’s social media when the female teacher Gu Shaoqiang (顾少强) at Zhengzhou’s Henan Experimental High School resigned from her job.

Working as a psychology teacher for 11 years, she gave a class in which she made students write a letter to their future self. The exercise made her realize that she, too, wanted more from life. Despite having little savings, she submitted a simple resignation note that read: “The world is so big, I want to go out and see it.”

The resignation letter was approved, and she posted it to social media.

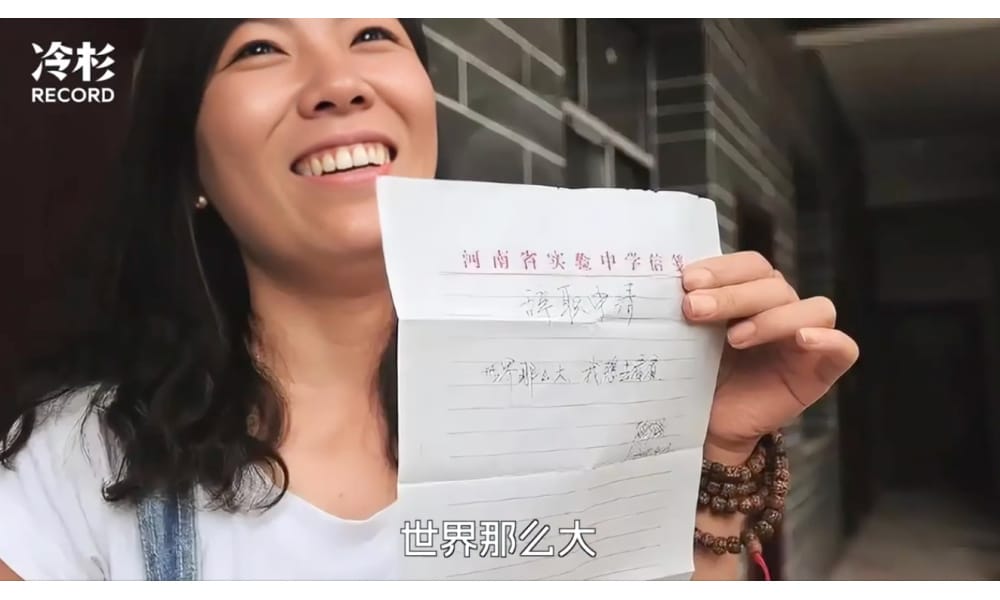

The resignation note that went viral, saying: “The world is so big, I want to go out and see it.”

The letter resonated with millions of Chinese who felt they also wanted to do something different with their life, like go and travel, see the world, and escape the pressures and routines of their daily life.

The phrase became so popular that it was adapted in all kinds of ways and manners, by meme creators, in books, by brands, and even by Xi Jinping, who said: “China’s market is so big, we welcome everyone to come and see it” (“中国市场这么大,欢迎大家都来看看”).

This week, Lěngshān Record (冷杉Record), the Wechat account under Chinese media outlet Phoenix Weekly (凤凰周刊), revisited the phrase and published a short documentary about Gu’s life after the resignation and the hype surrounding it.

An earlier news article about Gu’s life post-resignation already disclosed that Gu, despite receiving many sponsorship deals, never actually extensively traveled the world.

Gu and the viral resignation letter.

In the short documentary, Gu explains that she chose to “return home after seeing the world.” By this, she doesn’t mean traveling extensively abroad, but rather gaining life experience in a broader sense. While she did travel, it was within China, including in Tibet and Qinghai.

What truly changed was her life path. She left Zhengzhou and relocated to Chengdu to be near Yu Fu (于夫), a man she had met just weeks earlier by chance during a trip to Yunnan.

Six months after the resignation letter, she married him. Together, they ended up opening a hostel near Chengdu, married, and had a daughter.

Gu, now 45 years old, has been back in her hometown of Zhengzhou for the past years, caring for her aging mother and 9-year-old daughter. She is living separately from her husband, who manages their business in Chengdu. She also runs her own livestreaming and online parenting consultancy business.

Although the woman who wanted to “see the world” ended up back home, she has zero regrets about what she did, suggesting her courage to step out of the life she found limiting ultimately transformed her in a meaningful way.

On Chinese social media, the topic went trending on March 19. Most people cannot believe it’s already been ten years since the sentence went trending (“What? How could time fly like that?”).

Others, however, wonder about the hopes and dreams behind the original message—and how it all turned out.

“Seeing the world? She just escaped her old life, got married, and had a baby. How is that ‘seeing the world’?” one commenter wondered (@-NANA酱- ).

“The world is so big—what did she end up seeing?” others questioned. “She went from Zhengzhou to Chengdu.”

“Seeing the world takes money,” some pointed out.

But others came to her defense, saying that “seeing the world” also means stepping out of your comfort zone and exploring a different life. In the end, Gu certainly did just that.

“She was quite courageous,” another commenter wrote: “She gave up a stable job to go and see the world. Perhaps her life didn’t end up so rich, but the experiences she gained are priceless.”

The world is still big, though, and there’s plenty left for Gu Shaoqiang to see.

Read what we wrote about this in 2015: In The Digital Age, ‘Handwritten Weibo’ Have Become All The Rage

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

What’s on Weibo Chapters

Subscribe

Squat or Sit? China’s Great Toilet Debate and the Problem of Footprints on the Seat

Weibo Watch: The Great Squat vs Sitting Toilet Debate in China🧻

Chinese Netizens Turn to Tim Cook Over Battery Factory’s Illegal Overtime

Revisiting China’s Most Viral Resignation Letter: “The World Is So Big, I Want to Go and See It”

The 315 Gala: A Night of Scandals, A Year of Distrust

Our Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Beyond the Box Office: What’s Behind Ne Zha 2’s Success?

Weibo Watch: Christmas in China Is Everywhere and Nowhere

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

12-Year-Old Girl from Shandong Gets Infected with HPV: Viral Case Exposes Failures in Protecting Minors

15 Years of Weibo: The Evolution of China’s Social Media Giant

Tuning Into the Year of the Snake

The ‘China-chic Girl’ Image and the Realities of China’s Competitive Food Delivery Market

TikTok Refugees, Xiaohongshu, and the Letters from Li Hua

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight11 months ago

China Insight11 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music12 months ago

China Music12 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

-

China Arts & Entertainment10 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment10 months agoSinging Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments