China Health & Science

The Essential Balm: How to Use Tiger Balm & Qing Liang You

The best ways to use Tiger Balm according to Chinese social media users.

Published

6 years agoon

Some Chinese social media users claim Tiger Balm (or ‘Essential Balm’) is a “cure-all” product (包治百病) – why this century-old product is still popular today: the how-to-use tips from Weibo users.

What is simply known as ‘Tiger Balm’ in most Western countries, is also known as Fēng yóu jīng (风油精, lit. ‘wind oil’) or Qīng liáng yóu (清凉油, lit. ‘cool oil’) in China, usually translated as ‘Essential Balm.’

The translation ‘essential’ is quite literal in the sense that the balm is in fact essential to many Chinese households; virtually all pharmacies, supermarkets, airports shops and convenience stores in the PRC will sell it.

The over-the-counter balm (or oil) is a product that often pops up on Chinese social media. A recent video on streaming platform Billibilli calls it a “cure-all” product (包治百病), while netizens on Weibo share tips on how they use the balm on a daily basis.

Qingliangyou and fengyoujing; the essential oils/balms, via Billibilli.

The Tiger Balm brand name in Chinese is Hǔbiao Wànjīnyóu (虎標萬金油), which literally means ‘tiger-marked jack of all trades.’

All of these balms or oils are practically the same kind of ‘heat rubs,’ topical preparations for application to the skin, mainly made from menthol, camphor, clove oil, mint oil, and cajuput/eucalyptus oil.

The Chinese fengyoujing is an oily liquid that comes in a small bottle (10ml), while both the Tiger Balm brand and so-called ‘Essential Balm’ (various brands) come as balsam in a small tin. Because the first-mentioned is more easily applied as liquid, its effects are somewhat stronger than the balm.

A Tiger Balm History

The original Tiger Balm was developed in Birma in the 1870s, by the Fujian-born herbalist Aw Chu Kin (Hu Ziqin 胡子钦). Different to what the name suggests, Tiger Balm does not contain any ingredients related to the tiger, but was named after Aw’s son, whose name literally meant ‘Gentle Tiger’ (Aw Boonhaw or Hu Wenhu 胡文虎).

He was the son who later inherited the recipe of the balm, and turned Tiger Balm into a household name together with his brother (Hu Wenbao 胡文豹).

Aw Chu Kin was born in a small village. His father was also a herbalist, but the family was very poor. In search for a better live, the young Aw later moved to Birma (Myanmar), where he set up his own apothecary in Yangon in 1870 under the name of ‘Eng Aun Tong’ (永安堂药行).

Aw had three sons and a daughter. When he passed away in 1908, he left his company to the two sons who had helped him with his business. They later moved to Singapore, where they continued their father’s business and officially launched Tiger Balm as a brand in 1925, based on their father’s recipes.

The brothers used a remarkable promotion method for their balm; from 1926 on, they drove a vehicle that had a big tiger head on its front (see image). The horn of the car sounded like a tiger roar – a good way to attract the attention of people and to give them some free samples of their balm.

How to Use Tiger Balm: General Uses

The century-old product is still wildly popular today, with various companies now producing (nearly) identical products.

Note: not recommended to use for pregnant women, children under the age of 3, avoid contact with eyes, keep out of reach of children, and do not apply to injured skin or burns. If you’re in doubt about tiger balm usages and/or allergies, consult a doctor before using.

Among the main purposes of Tiger Balm and Qing Liang You is that it can be used as an anti-itching remedy for mosquito bites and insect stings.

For those with rheumatic pains, tiger balm can be also used as a painkiller by applying it in the lower back area, legs, and directly on sore muscles and bones.

Tiger Balm is also said to be helpful against a cold and have a stuffed nose, by putting some balm right underneath and around the nostrils to let the nose clear up.

To prevent dizziness and carsickness, the balm can be used to slightly moisten the lips or temples to prevent nausea.

Social Media Tips

On Weibo, dozens of people share their use of Tiger Balm and the likes on their accounts every day – especially during the hot summer.

* Some Chinese students simply recommend keeping a small tin of balm nearby for those late study hours; they claim sniffing the balm awakens the mind.

* “I apply some balm before I take a shower,” one commenter says: “Now my whole body feels cool as a breeze.” By applying some balm to parts of the body, the skin gets cooled – a comfortable feeling in times of hot weather or fever.

* Social media user Xixi (@西西咕噜咕噜) uses Tiger Balm in hot summer days. Opening up the lid of the balm a few times a day in front of the van spreads its cooling breeze throughout the room: “I’m crazy about this fragrance.” (Tip! Mosquitos and other insects dislike this smell; this method is also effective as a repellent.)

* “I’ve been suffering from a head-ache for days,” a Weibo user named ‘I’ve been studying for hours today’ (@今儿学了几个小时) says: “Rubbing some qingliangyou on my temples really helps.” Tiger balm is often promoted as a remedy against headache, by rubbing some tiger balm on the forehead or temples (mind your eyes).

* “After cutting red peppers, you can smear some Tiger Balm on your fingers,” another Weibo user (@萍了早煤) writes: “also use some plain vinegar to wash it off. It helps.”

* “You can use Tiger Balm / Qing Liang You to improve blood circulation and decrease swellings,” one Guangdong micro-blogger writes. It is indeed said that one of the active ingredients, camphor, dilates the blood vessels and brings blood closer to the skin’s surface; increasing circulation and warmth.

* Another popular Weibo account (@好运逗比) recommends rubbing some drops of the fengyoujing (the liquid rub) to the soles of the feet before wearing shoes to prevent smelly feet at the end of the day.

* There are also Weibo accounts recommending Tiger Balm / Qing Liang You as the must-bring item on travels to prevent mosquito bites, car or sea sickness, and for treatment of headaches.

* There are also some people who say they use Tiger Balm on their face as a way to treat acne/pimples, but we’d highly recommend consulting with a doctor before doing so, as the balm is not recommended to be used on irritable skin.

Still not had enough tips? You can check out one of What’s on Weibo’s earliest articles, titled ‘20 Ways to Use Tiger Balm,’ for more tips on how to use this ‘jack for all trades’ balm.

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

Where to Buy

Tiger Balm is practically available everywhere. Check your local pharmacy or convenience store. The brand also has an online shop where their products can be purchased. For small cases of essential balm to carry with you at all times check here.

The Temple of Heaven balm can be purchased at Beijing airport and many other places, but online it is purchasable here.

The classic oil, which is somewhat stronger, is available here.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2018 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Health & Science

Breaking the Taboo: China’s Sanitary Pad Controversy Sparks Demand for Change

After realizing domestic sanitary pads were literally falling short, Chinese netizens are demanding greater awareness and improvements in long-overlooked issues of quality, affordability, and societal attitudes toward menstruation.

Published

2 weeks agoon

December 6, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

Sanitary pads have never been a bigger topic of debate on Chinese social media as it’s been over the past few weeks. What began with one blogger’s discovery of menstrual pads falling short of their advertised size has grown into a broader movement, demanding better-quality products and greater awareness of menstrual health.

Despite being a natural part of life for women around the world, menstruation remains a sensitive and taboo subject in many parts of China, particularly in more conservative, rural areas and smaller cities.

Essential feminine hygiene products like sanitary pads or tampons are often discreetly wrapped in dark plastic bags to avoid drawing attention.

However, this month, the silence was broken. “Sanitary pads” and related topics dominated online discussions, igniting a heated conversation that started with pad length but quickly expanded to include concerns about health, safety, and women’s rights.

EXPOSING THE “SHORTCOMINGS” IN SANITARY PADS

“Buy it if you want, or just don’t.”

In early November, a viral post on Xiaohongshu (later deleted) brought attention to a troubling issue. A woman who purchased sanitary pads online found them significantly shorter than advertised—a supposed 290mm pad measured only 250mm.

When she confronted the seller, they dismissed her concerns, citing a “normal 4% margin of error” and claiming, “If you order 290mm, we can only send 250mm—that’s the rule.”

The post struck a nerve. Netizens began measuring their own pads and discovered that many brands similarly fell short of their advertised lengths. This perceived deception ignited widespread outrage:

“They market themselves as designed for women, but even the lengths are misleading?”

“We pay the highest taxes for subpar products!”

The controversy soon spread to platforms like Douban and Weibo, where more and more people started comparing advertised versus actual pad lengths. The results revealed that many well-known brands consistently fell short, raising accusations of industry-wide cost-cutting.

Facing mounting pressure, several Chinese brands issued responses claiming their products adhered to the national standard that allows a ±4% length deviation. According to this standard, a 290mm pad can legally measure between 278mm and 302mm.

However, consumer measurements consistently showed pads at the lower limit—or even shorter. This raised suspicions that manufacturers were exploiting the -4% allowance as an industry norm to cut costs.

Some netizens compiled a crowdsourced chart comparing the advertised length, actual length, and cotton coverage of various brands. The findings revealed similar discrepancies across major brands.

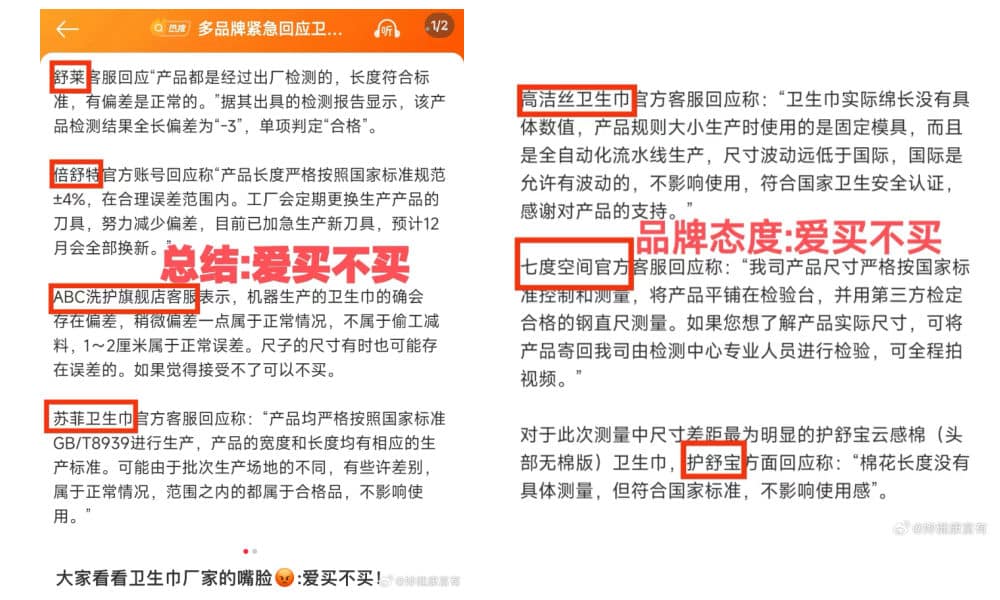

Various brands’ responses to the controversy listed by blogger @妳健康富有.

Some brands, with size deviations as large as -15%, responded evasively to consumer concerns, claiming that such deviations are normal and do not affect usage. These responses only fueled further frustration among netizens, who accused the brands of dismissing their concerns. As one blogger (@你健康富有) remarked, the brands’ attitude couldn’t be clearer: “‘Buy it if you want, or just don’t.'”

BEYOND LENGTH: A DEEPER ISSUE

“Society tolerates or even reinforces menstrual stigma.”

While the pad length scandal initially focused on cost-cutting, the ensuing discussions uncovered far more serious concerns. A resurfaced video by documentary filmmaker and blogger Fourfire (四火, @为了玲飞护肤纪录片) revealed the industry’s dark side. The video exposed illegal factories recycling used materials, including shredded pads and diapers, into new sanitary products. These contaminated pads, sold cheaply on e-commerce platforms, have been linked to pelvic inflammation and other gynecological problems.

In the video, Fourfire urged women to stick to well-known brands and purchase from reputable retailers.

Still from the video by documentary filmmaker and blogger Fourfire (四火, @为了玲飞护肤纪录片)

But are pricier pads from major retailers truly safe? Quality issues with domestic brands have surfaced repeatedly, and this latest length discussion reignited those concerns. Consumer-created “red-flagged brands” for domestic pads feature numerous well-known brands with prior reports of containing maggots, mold, and other contaminants.

This renewed scrutiny prompted questions and discussions among female netizens. One user asked, “Is there any brand of sanitary pads that’s actually safe to use?” Among the hundreds of replies and shares, one prevailing sentiment emerged: “None of them.” Many users began to view previous quality issues not as isolated incidents but as indicative of broader problems within the industry.

Adding fuel to the fire, one blogger (@迷宝吃不饱) claimed that the national standards for sanitary pads in China allow a pH range of 4–9. This range aligns with standards for non-intimate textiles, such as jackets or curtains. Given that human skin is slightly acidic, with a pH between 4.1 and 5.8 (3.8–4.5 for intimate zones), products in close contact with the skin, such as sanitary pads, should ideally be designed to maintain the skin’s natural pH balance and prevent irritation.

This seemingly loose standard sparked further concerns among female consumers. Many began reflecting on their past experiences, sharing issues they’d faced while using sanitary pads—frequent inflammation, allergic reactions, itching, and other symptoms. Few had considered the possibility that these problems might be linked to the pads themselves.

In response, experts argued that the materials, hygiene, and sterilization of pads were far more critical than pH levels. However, in today’s China, where public trust in such authorities is relatively low (read: “Experts Are Advised Not to Advise“), this explanation not exactly reassured the public. Gynecologists and popular science influencers, such as Sixthfloor (@六层楼先生), pointed out that similar products like baby diapers and men’s sanitary pads are held to stricter production standards. This disparity naturally fueled suspicion and concern about women being disadvantaged and the role of societal taboos surrounding menstruation.

One Douban user commented: “Society tolerates or even reinforces menstrual stigma. The less we talk about sanitary pads, the easier it is for companies to profit from women.”

BREAKING THE SILENCE

“Decisions about menstrual products are being made by people who don’t menstruate.”

Sanitary pads in China are relatively expensive and not covered by health insurance. A single daytime pad from a common brand costs around 1 RMB ($0.15), while nighttime pads can be twice as expensive. Over a typical six-day period, a woman might spend 30-40 RMB ($4.15-$5.50) each month. Tampons, though less popular in China, are even more costly.

For women in impoverished or rural areas, this expense can be a significant burden. Many are forced to purchase low-cost, unregulated “three-no” products (no license, no standards, no brand), often manufactured by the shady companies exposed in Fourfire’s video. On Taobao, product reviews for these pads reveal heartbreaking stories. Some users recommend switching to safer, higher-quality options, but responses often reflect the harsh reality: “I don’t have a choice.”

Now, as major brands face public backlash, many women are turning to “medical-grade sanitary pads,” originally made for surgical recovery or heavy bleeding. According to the Sichuan Observation media channel (@四川观察), online searches for these products have jumped by over 3,000%. While safer, these pads are even more expensive.

The frustration is clear: “Do we really have to keep paying more for basic necessities just to protect our health? Why not just make regular sanitary pads safe and reliable? Is that too much to ask?”

So why is it so hard to produce affordable, safe sanitary pads without cost-cutting tricks? The answer may lie in a regulatory change made over a decade ago. In 2008, new national standards for sanitary pads eliminated quality grading classifications and reduced minimum requirements for the length of filling cotton. This gave manufacturers more freedom to cut costs, often at the expense of quality.

One glaring detail hasn’t gone unnoticed: the revised standards were drafted entirely by men. As one netizen commented, “Decisions about menstrual products are being made by people who don’t menstruate.” For women, the lack of female representation in an industry directly affecting them is both absurd and infuriating, highlighting a deeper issue of gender imbalance in industries and regulatory frameworks that shape women’s lives.

At the time of writing, distrust in domestic sanitary pad brands in China has reached a peak. Whether driven by exaggerated fears or valid concerns, one thing is clear: after years of menstrual stigma and neglect of women’s health issues, many women feel unheard and are now speaking out. This growing frustration has given rise to an online feminist movement, calling for accountability and demanding change from an industry—and a culture—that has long overlooked some of women’s basic rights.

GRASSROOTS EFFORTS FOR CHANGE

“Girls should never feel ashamed of their periods”

With policymakers mostly male, Chinese women have had to take matters into their own hands. Over the years, various incidents related to menstrual products have gone viral and triggered grassroots efforts to improve the status quo.

The last major public outcry about sanitary pads occurred in 2022 when a woman on a high-speed train discovered they weren’t available for purchase. She vented her frustration online, and the issue quickly gained traction. Many commenters, mostly men, argued that pads weren’t “essential items” and didn’t warrant taking up retail space onboard. The railway authority’s official response—categorizing sanitary pads as “personal items” that didn’t need to be sold—only intensified the outrage.

In the same year, a young woman in Covid quarantine in Xi’an went viral after she tearfully begged anti-epidemic staff for sanitary pads. When workers at her quarantine hotel told her there was nothing they could do, she asked, “So what? Does that mean I have to bleed a river of blood?”

For many women, these incidents highlighted how little society understands or respects their basic needs. In response, people organized online campaigns, flooded hotlines with complaints, and raised awareness about why menstrual products are essential. “Girls should never feel ashamed of their periods,” one netizen wrote.

Sometimes, progress is made. The woman in Xi’an’s quarantine later posted an update, saying she eventually received the menstrual pads she needed. And although pads are still not available on all high-speed trains, they are now provided on many routes—a small but meaningful step.

This time, the debate over pad quality has drawn even greater attention, involving public figures, celebrities, and even tech mogul and Xiaomi founder Lei Jun (雷军), with some hoping that a trusted brand like Xiaomi could play a role in making Chinese sanitary pads safer and more innovative. Women have launched cross-platform campaigns like #ShowYourSanitaryPads (#晒出你的卫生巾#), encouraging people to share posts on Weibo, Douban, and Xiaohongshu to call out brands for inaccurate sizing or poor quality.

Activists are also sharing step-by-step guides on filing formal complaints and advocating for stricter national production standards. The movement is gaining momentum, driven by a collective determination to demand safer, more reliable products.

On November 21, China News Weekly reported that a new national standard for sanitary pads is being drafted. CNR News also called for tighter industry oversight, signaling an urgent response to recent public criticism.

Yet, this response only scratches the surface of the deeper issues surrounding menstrual products in China. Challenges such as the high cost of pads, their limited availability in public spaces, and inadequate menstrual education persist. Will meaningful change continue to rely solely on grassroots efforts? Hopefully, this marks the beginning of a broader, systemic shift that not only addresses these immediate concerns but also redefines how society values and prioritizes women’s basic needs.

By Ruixin Zhang

Independently covering digital China for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Health & Science

Stolen Bodies, Censored Headlines: Shanxi Aorui’s Human Bone Scandal

A Chinese company illegally acquired thousands of corpses to produce bone graft materials sold to hospitals—a major scandal now being tightly controlled on social media.

Published

4 months agoon

August 9, 2024

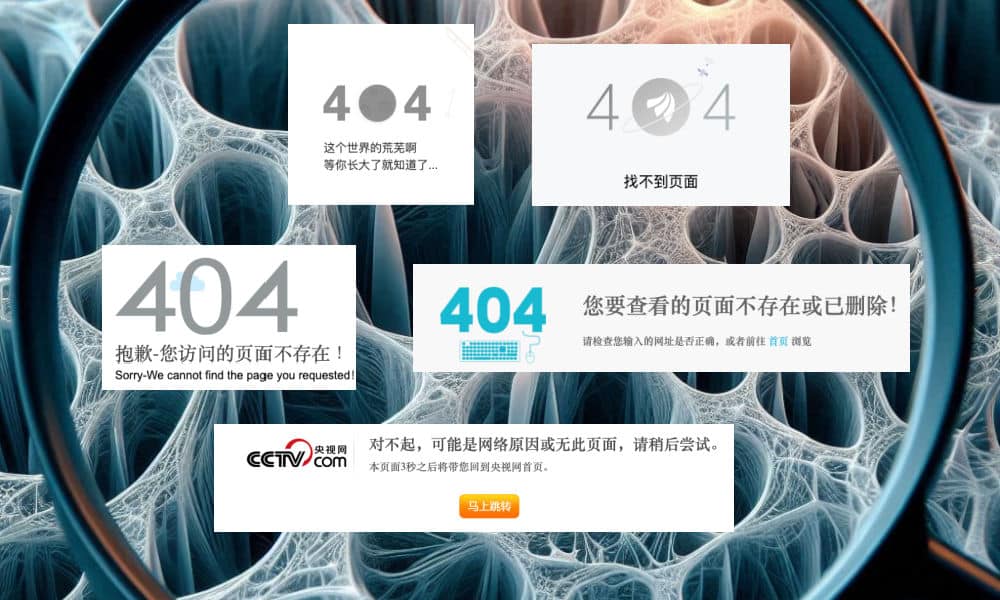

On Thursday night, August 8, while most trending topic lists on Weibo were all about the Olympics, a new and remarkable topic suddenly rose to the number one, namely that about the “Illegal Human Bone Case.” Just moments later, however, the topic had already disappeared from the Weibo hot search list.

An article about the topic by Chinese media outlet The Paper (澎湃)1 that had just been published hours earlier on August 8 had already been taken offline. Later, an article published on The Observer (观察)2 was also redirected. Another article published on the website of Caixin and state broadcaster CCTV similarly disappeared, 3 along with many other headlines.4

However, at the time of writing, there are some articles on the issue, such as by Sina News or Phoenix News, that remained accessible.

The story centers on Shanxi Aorui Bio-Materials Co., Ltd. (山西奥瑞生物材料有限公司), also known as Shanxi Osteorad in English, a company founded in 1999 that specializes in the production and supply of bone graft products.

On August 7, a prominent Chinese lawyer named Yi Shenghua (易胜华), who has a large following on Weibo, exposed details of Shanxi Aorui’s involvement in illegal and unethical practices surrounding the purchase of human bones. The company engaged in these practices for over eight years, from January 2015 to June 2023, generating an income of 380 million yuan ($53 million) from these activities.

These details had previously been disclosed by the Taiyuan Public Security Bureau in May of this year. The case has allegedly been transferred to the Taiyuan Procuratorate for review and potential prosecution, but it has yet to be concluded due to its complexity, involving some 75 suspects.

Over the years, Shanxi Aorui illegally acquired thousands of human remains, reportedly forging body donation registration forms and other documents to illegally purchase bodies from hospitals, funeral homes, and crematoriums from various places, from Sichuan Guangxi, Shandong, and other places. These human remains were then used to produce allogeneic bone implant materials, primarily sold to hospitals.

Due to the high demand for bone implant materials and limited supply, it is an incredibly lucrative industry. Some reports claim that those selling the human remains to Shanxi Aorui could charge between 10,000 and 22,000 yuan per corpse ($1400-$3000).

“I’ve been a criminal lawyer for many years, and have handled all kinds of cases, but this is the first time for me to be so shocked and angry,” Yi Shenghua wrote in his post (screenshot available via RFA.org).”What makes me particularly lose hope is that the maximum punishment for these kinds of people under the current law is only three years.”

However, Yi Shenghua’s Weibo post about the issue was later blocked from public view. “I can still see my own post, but apparently, others cannot,” Yi wrote at 17:35 on Thursday.

On August 9, China’s major pharmaceutical company Sinopharm issued a statement in light of the controversy surrounding the human bone case, stating it has never had any kind of relationship with the Shanxi Aorui company.

On Friday, the news topic on Chinese social media was tightly controlled. Various media outlets, from Weibo to Douyin, reported on the issue, but despite the public’s interest in the scandal, not a single comment could be seen under multiple threads.

‘Even Douyin blocked the Shanxi Aorui incident. Is this the government stepping in?’ one commenter wondered.

‘Why are they suppressing this hot search topic? Do they think the public is stupid?’ another person wrote.

One individual implicated in this case is Li Baoxing (李宝兴, born 1955), who was General Manager at Shanxi Aorui. Li is a renowned research professor who was reportedly awarded the title of National Model Worker in 2005. He was formerly affiliated with the Institute of Biomaterials Science and Technology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, where he developed bone implant materials that benefited thousands of patients across the country. He allegedly joined the Communist Party in 1985.

Some commenters called the entire scandal a “horror film,” with Li Baoxing being the director.

“We know about 4000 [human remains], what about those we don’t know about?”

“These so-called ‘human remains’ were once people like you and me,” another Weibo user wrote: “They were alive, their voices and smile are still in the hearts of family and friends. They liked to be clean, they had their privacy, they are still being missed. We can’t replace ourselves or our loved ones, [yet] they were used and peeled layer by layer.”

By Manya Koetse

1 Title: “探访涉盗卖数千具人体骨骼的山西奥瑞公司,此前已被公安查封” (“Investigation into Shanxi Aorui Bio, involved in the illegal sale of thousands of human bones, which had previously been seized by police”). Original link: https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_28348324

2 Title: “涉嫌非法盗卖数千具遗体用于制作植入材料,山西奥瑞生物八年营收3.8亿” (“Suspected of illegally stealing and selling thousands of human remains for use in making implant materials, Shanxi Aorui Bio made an eight-year revenue of 380 million yuan”). Original link: https://www.guancha.cn/GongSi/2024_08_08_744234.shtml

3 CCTV’s publication is the same as the article published by The Paper, namely: “探访涉盗卖数千具人体骨骼的山西奥瑞公司,此前已被公安查封” (“Investigation into Shanxi Aorui Bio, involved in the illegal sale of thousands of human bones, which had previously been seized by police”). Original link: https://news.cctv.com/2024/08/08/ARTIkxoJEQuHmvTxmxGVmDug240808.shtml. Caixin’s publication was titled “75人卷入山西盗窃倒卖遗体案 多地民政局称已跟进调查” (75 people involved in the theft and sale of human remains in Shanxi, investigations underway by various civil affairs bureaus).

4 For example, by Sina News: “起底倒卖4000具尸体操控者李宝兴- 曾获“全国劳模”称号” (“Li Baoxing, the manipulator who speculated in 4,000 corpses, was awarded the title of “national labor model”). Original link: https://finance.sina.com.cn/chanjing/gsnews/2024-08-08/doc-inchxqva1690315.shtml?cre=sinapc&mod=g.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

12-Year-Old Girl from Shandong Gets Infected with HPV: Viral Case Exposes Failures in Protecting Minors

Explaining the Bu Xiaohua Case: How One Woman’s Disappearance Captured Nationwide Attention in China

Story of Chinese Female MA Graduate Going Missing for 13 Years Sparks Online Storm

Weibo Watch: China’s Online Feminism Is Everywhere

Why Chinese Hit Movie “Her Story” is ‘Good Stuff’: Stirring Controversy and Celebrating Female Perspectives

Death of Chinese Female Motorcycle Influencer ‘Shigao ProMax’ Sparks Debate on Risky Rides for Online Attention

Hidden Hotel Cameras in Shijiazhuang: Controversy and Growing Distrust

Weibo Watch: Small Earthquakes in Wuhan

The Price of Writing Smut: Inside China’s Crackdown on Erotic Fiction

Why the “人人人人景点人人人人” Hashtag is Trending Again on Chinese Social Media

The Hashtagification of Chinese Propaganda

Controversial Wanghong Livestreamers Are Becoming a Weibo Staple in China

Weibo Watch: “Comrade Trump Returns to the Palace”

The ‘Cycling to Kaifeng’ Trend: How It Started, How It’s Going

Hu Xijin’s Comeback to Weibo

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight7 months ago

China Insight7 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music9 months ago

China Music9 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Insight10 months ago

China Insight10 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Digital7 months ago

China Digital7 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI