China Media

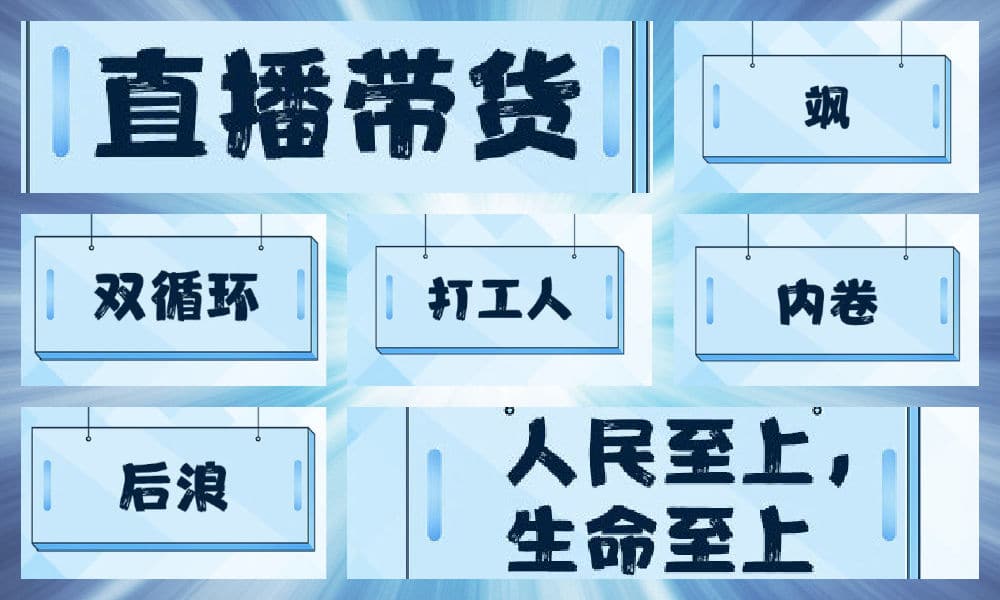

The Top 10 Buzzwords in Chinese Online Media in 2020 (咬文嚼字)

Some of the buzzwords that were most noteworthy in Chinese media this year.

Published

4 years agoon

By

Jialing Xie

These are some of the expressions and idioms that have been buzzing in Chinese media in 2020. What’s on Weibo’s Jialing Xie explains.

China’s online media environment is a breeding ground for new terms and niche expressions that suddenly make it to mainstream discussions.

Every year, the most popular new words and expressions are listed by the Chinese magazine 咬文嚼字 (yǎo wén jiáo zì). The magazine selects buzzwords that reflect present-day society and the changing times.

Yǎo Wén Jiáozì, which means “to pay excessive attention to wording,”* is a monthly publication featuring commentary, criticism, and essays on the Chinese language.

Founded in 1995, the magazine has gained social influence for correcting typos in the language used by media and celebrities. Some of these corrections have been impactful, such as their correction of the 2006 CCTV Chinese New Year Gala on writing ‘Shenzhou 6’ (the second human spaceflight of the Chinese space program) as “神州六号” rather than “神舟六号” (different character for ‘zhōu’). It was included in their “Ten Biggest Language Mistakes” list (十大语文差错) of that year.

On social media, Chinese online (state) media always promote the magazine’s selection of the top words and terms of the past year. The ten terms have also become a relatively big topic on Weibo over the past month, with the list of Top 10 Buzzwords in 2020 #2020年度十大流行语# already garnering 460 million views.

*yǎo wén jiáo zì, literal meaning: to talk pedantically and pay excessive attention to wording, often referring to a stickler for detail with an intent to display their fine knowledge; often used negatively or neutrally.

We’ve listed the top 10 buzzwords for you here:

1. 人民至上,生命至上 (Rénmín zhìshàng, shēngmìng zhìshàng): “People First”

- Literal Meaning: “People are above everything else, life is above everything else.”

- The context of this phrase in 2020: On May 22 of 2020, Chinese President Xi Jinping took part in the deliberation of the Inner Mongolia delegation at the annual legislative session, where he stated that “our people come first, people’s lives come first, and the safety and health of our people should be secured at all costs.” “People first, life first” has since become a widely circulated slogan and guiding principle for government and society to combat Covid-19 across the country.

2. 逆行者 (Nìxíng zhě): “People Going against the Tide”

- Literal Meaning: “People who swim upstream / people who go against the current.”

- The context of this phrase in 2020: In a broad sense, this phrase shares a similar meaning as its English counterpart, describing people who dare to differ from the mainstream and to go above and beyond their call of duty. In 2020, it has become a term often used by state media to refer to frontline workers and individuals who made a significant contribution or sacrifice during the battle against the novel coronavirus.

3. 飒 (Sà): “Spirited”

- Literal Meaning: “1) Chill and refreshing 2) Onomatopoeia: the sound of the wind

- The context of this word in 2020: In modern Chinese literature, this word is commonly used in the idiom “英姿飒爽” (yīng zī sà shuǎng), illustrating how a person, either a man or woman, is high of energy and full of morale and is showing an attitude of heroism and prestige. According to People’s Daily, half of the doctors and more than 90% of the nurses working in healthcare during the fight against COVID19 are female. State media started to use 飒 (sà) as an adjective to eulogize these female medical workers. The word was later used to praise both men and women working in other industries as well.

4. 后浪 (Hòu làng): “The Rear Waves”

- Literal Meaning: “The rear waves.”

- The context of this phrase in 2020: 后浪 hòulàng is often used within the idiom “长江后浪推前浪” (cháng jiāng hòu làng tuī qián làng) which literally means “the rear waves in the Yangtze River drive on those before,” and figuratively referring to how the new generation excels beyond the one before, or how the new is constantly replacing the old. This phrase became an internet meme regarding the young generation in China – specifically, those born in the 90s and 00s – as a result of heated online discussions about a video launched on Bilibili and other social media for Youth Day (May 4th), in which the older actor He Bing talks about the rights and opportunities enjoyed by young people in China today. On various occasions, this word is used to address the more privileged young people. Some associated stereotypes about this group include studying or living abroad, high-quality lifestyle, and luxury material possessions. Those who don’t identify with this privileged group tend to refer to themselves as “韭菜” (Jiǔcài, chives), which shares a similar sentiment as “屌丝” (Diǎosī, loser), as opposed to “the rear waves.”

5. 神兽 (Shén shòu): “Divine Beasts”

- Literal Meaning: “Divine beasts.”

- The context of this word in 2020: Totem worshiping is deeply rooted in the religion and tradition of many ancient cultures. Divine beasts in China are in fact deities, also known as the Four Symbols (四象), as a mixed product of Chinese ancient cosmology and mythology. Since the beginning of remote learning and delay in schools reopening across the country, many parents and caregivers have posted their experience balancing work and remote learning with their children from home. In these posts, parents often call their children ‘divine beasts’ then share their children’s naughty behavior and how they struggled to deal with them.

6. 直播带货 (Zhíbò dài huò): “Live commerce”

- Literal Meaning: “Live commerce”, “Influencer marketing via live streaming.“

- The context of this phrase in 2020: China’s live-streaming economy played an important role in the country’s economic market recovery amidst COVID19. Influencer marketing via live streaming combines talk show-like entertainment and the convenience of online shopping, at times even leveraging social proof and the reputation of influencers themselves to crack astonishing sales records. Apart from internet celebrities, many business executives (i.e. Jack Ma) and even government officials (i.e. 13 local mayors in Hubei Province) also took advantage of the booming live-streaming and appeared in front of webcams to promote certain products which resulted in millions of views on TikTok. On the flip-side of the business, there have been concerns about the quality of the products as well as lawsuits against fraudulent sales practices. Popular topics on Weibo as such include #如何看待直播带货卖假货#(“What do you think of counterfeit goods in live-streaming sales”).

7. 双循环 (Shuāng xún huán): “Dual Cycle”

- Literal Meaning: “Dual cycle.”

- The context of this word in 2020: This term comes from President Xi’s speech at the meeting of the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party on May 4, 2020, during which he stated that the dual-cycle system will be the party’s strategy for China’s economic and political development for the near future following COVID19 recovery. The system focuses on recovering and growing the economy by primarily expanding domestic demand mixed with healthy participation in international trade. While it certainly was not the first time the Communist Party introduced this concept of prioritizing the domestic market, according to Xinhua News Agency, the dual-cycle system has been regarded as a suitable strategy given current restrictions facing international trade due to the pandemic and the ongoing trade tensions between China and a few western powers.

8. 打工人 (Dǎ gōng rén): “Working People”

- Literal Meaning: “Working people”

- The context of this phrase in 2020: As agriculture, foreign trade, and investment sectors developed following the economic reform in 1978, a social-economic trend emerged in the 80s during which labor forces across China’s villages and countrysides migrated to cities and worked in blue-collar jobs. These migrant workers are called 打工人 (Dǎ gōng rén) / 打工仔 (Dǎ gōng zǎi). The word later evolved and was used to address the entire working class and salaried employees. For example, the memoir written by Shujuan Liu of the former president of Microsoft China, Jun Tang, was titled “I’m the 高级打工仔 (Gāojí dǎgōng zǎi, high-class worker) at Microsoft”. The term was frequently used as an internet buzzword in 2020 after appearing in a viral video in which a man acted as a migrant worker and showed watchers warm and positive encouragement. The video ended with a “good morning” greeting and addressed watchers as 打工人.

9. 内卷 (Nèi juǎn): “Involution”

- Literal Meaning: “Involution“

- The context of this phrase in 2020: According to People’s Daily, this word is a direct translation of the concept of ‘involution’ brought up by the American anthropologist Clifford Geertz. Involution describes the economic situation in which as the population grows, per capita wealth decreases. This year, this word is used to represent the competitive circumstances in academic or professional settings where individuals are compelled to overwork because of the standard raised by their peers who appear to be even more hard working. In the latter half of 2020, a few pictures capturing college students’ multitasking went viral on Weibo. One of the images shows a person working on his computer while riding his bike. These people were then called “卷王” (Juǎn wáng, meaning they are the example of overworking) on social media and became the origin of this buzzword. You can find this word sometimes associated with the 996 working hour system on Weibo.

10. 凡尔赛文学 (Fán’ěrsài wénxué): “Versailles Literature”

- Literal Meaning: “Versailles literature.”

- The context of this phrase in 2020: Social media has made displaying wealth and superiority easier than ever before. Instead of showing off explicitly, some find a way to both satisfy their desire for publicity and avoid doing so ostentatiously, by flaunting wealth and material possessions in an indirect and often negative-toned message. This writing style for social media posts is then referred to as “Versailles literature.” Admittedly not all posts labeled as “Versailles literature” were written with the intent to show off, but those with clear intention are often easily spotted and circulated online and became funny memes. This then led to a wave of discussions and a contest of “Versailles literature” on social media, which became a form of entertainment itself.

By Jialing Xie

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2020 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Jialing is a Baruch College Business School graduate and a former student at the Beijing University of Technology. She currently works in the US-China business development industry in the San Francisco Bay Area. With a passion for literature and humanity studies, Jialing aims to deepen the general understanding of developments in contemporary China.

China Media

12-Year-Old Girl from Shandong Gets Infected with HPV: Viral Case Exposes Failures in Protecting Minors

A doctor in Tai’an faced resistance when she tried to report a 12-year-old girl’s HPV case. She then turned to social media instead.

Published

3 months agoon

December 18, 2024

A 12-year-old girl from Shandong was diagnosed with HPV at a local hospital. When a doctor attempted to report the case, she faced resistance. Weibo users are now criticizing how the incident was handled.

Over the past week, there has been significant uproar on Chinese social media regarding how authorities, official channels, and state media in China have handled cases of sexual abuse and rape involving female victims and male perpetrators, often portraying the perpetrators in a way that appears to diminish their culpability.

One earlier case, which we covered here, involved a mentally ill female MA graduate from Shanxi who had been missing for over 13 years. She was eventually found living in the home of a man who had been sexually exploiting her, resulting in at least two children. The initial police report described the situation as the woman being “taken in” or “sheltered” by the man, a phrasing that outraged many netizens for seemingly portraying the man as benevolent, despite his actions potentially constituting rape.

Adding to the outrage, it was later revealed that local authorities and villagers had been aware of the situation for years but failed to intervene or help the woman escape her circumstances.

Currently, another case trending online involves a 12-year-old girl from Tai’an, Shandong, who was admitted to the hospital in Xintai on December 12 after testing positive for HPV.

HPV stands for Human Papillomavirus, a common sexually transmitted infection that can infect both men and women. Over 80% of women experience HPV infection at least once in their lifetime. While most HPV infections clear naturally within two years, some high-risk HPV types can cause serious illness including cancer.

“How can you be sure she was sexually assaulted?”

The 12-year-old girl in question had initially sought treatment for pelvic inflammatory disease, but upon review, her doctor discovered that she had been previously treated for vaginitis six months earlier. During further discussions with the girl, the doctor learned she had been sexually active with a boy five years her senior and was no longer attending school.

Given that the age of consent in China is 14 years old, the doctor sought to report the case to authorities. However, this effort was reportedly met with resistance from the hospital’s medical department, where she was allegedly questioned: “How can you be sure she was sexually assaulted?”

When attempts to escalate the case to the women’s federation and health commission went unanswered, the doctor turned to a blogger she knew (@反射弧超长星人影九) for help in raising awareness.

The blogger shared the story on Weibo but failed to receive a response through private messages from the Tai’an Police. They then contacted a police-affiliated Weibo channel they were familiar with, which eventually succeeded in alerting the Shandong police, prompting the formation of an investigation team.

As a result, on December 16, the 17-year-old boy was arrested and is now facing legal criminal measures.

According to Morning News (@新闻晨报), the boy in question is the 17-year-old Li (李某某), who had been in contact with the girl through the internet since May of 2024 after which they reportedly “developed a romantic relationship” and had “sexual relations.”

Meanwhile, fearing for her job, the doctor reportedly convinced the blogger to delete or privatize the posts. The blogger was also contacted by the hospital, which had somehow obtained the blogger’s phone number, asking for the post to be taken down. Despite this, the case had already gone viral.

The blogger, meanwhile, expressed frustration after the case gained widespread media traction, accusing others of sharing it simply to generate traffic. They argued that once the police had intervened, their goal had been achieved.

But the case goes beyond this specific story alone, and sparked broader criticisms on Chinese social media. Netizens have pointed out systemic failures that did not protect the girl, including the child’s parents, her school, and the hospital’s medical department, all of whom appeared to have ignored or silenced the issue. As WeChat blogging account Xinwenge wrote: “They all tacitly colluded.”

Xinwenge also referenced another case from 2020 involving a minor in Dongguang, Liaoning, who was raped and subsequently underwent an abortion. After the girl’s mother reported the incident to the police, the procuratorate discovered that a hospital outpatient department had performed the abortion but failed to report it as required by law. The procuratorate notified the health bureau, which fined the hospital 20,000 yuan ($2745) and revoked the department’s license.

Didn’t the hospital in Tai’an also violate mandatory reporting requirements? Additionally, why did the school allow a 12-year-old girl to drop out of the compulsory education programme?

“This is not a “boyfriend” or a “romantic relationship.””

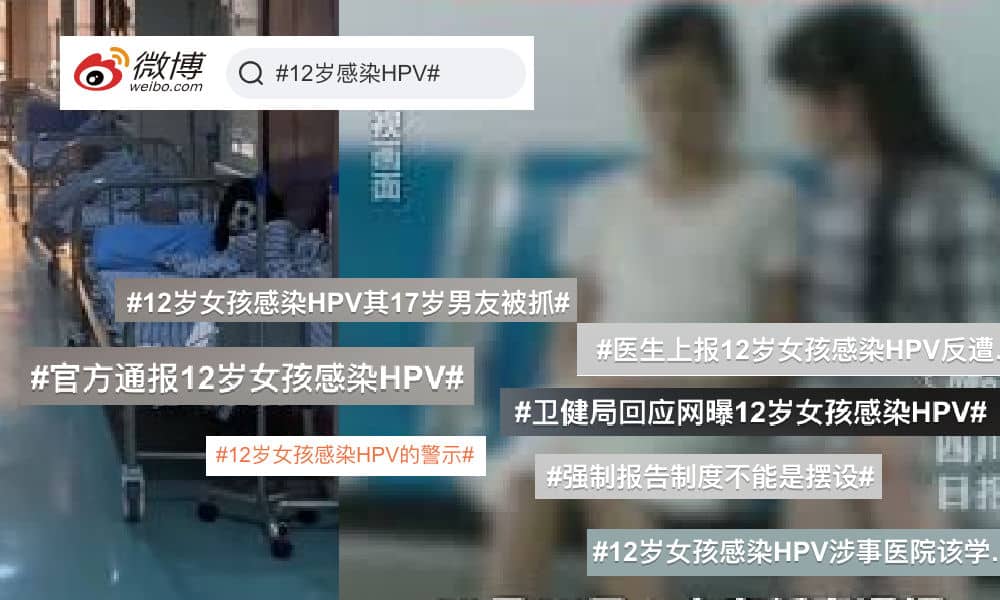

The media reporting surrounding this case also triggered anger, as it failed to accurately phrase the incident as involving a raped minor, instead describing it as a girl having ‘sexual relations’ with a much older ‘boyfriend.’

Under Chinese law, engaging in sexual activity with someone under 14, regardless of their perceived willingness, is considered statutory rape. A 12-year-old is legally unable to give consent to sexual activity.

“The [Weibo] hashtag should not be “12-Year-Old Infected with HPV, 17-Year-Old Boyfriend Arrested” (#12岁女孩感染HPV其17岁男友被抓#); it should instead be “17-Year-Old Boy Sexually Assaulted 12-Year-Old, Causing Her to Become Infected” (#17岁男孩性侵12岁女孩致其感染#).”

Another blogger wrote: “First, we had the MA graduate from Shanxi who was forced into marriage and having kids, and it was called “being sheltered.” Now, we have a little girl from Shandong being raped and contracting HPV, and it was called “having a boyfriend.” A twelve-year-old is just a child, a sixth-grader in elementary school, who had been sexually active for over six months. This is not a “boyfriend” or a “romantic relationship.” The proper way to say it is that a 17-year-old male lured and raped a 12-year-old girl, infecting her with HPV.”

By now, the case has garnered widespread attention. The hashtag “12-Year-Old Infected with HPV, 17-Year-Old Boyfriend Arrested” (#12岁女孩感染HPV其17岁男友被抓#) has been viewed over 160 million times on Weibo, while the hashtag “Official Notification on 12-Year-Old Infected with HPV” (#官方通报12岁女孩感染hpv#) has received over 90 million clicks.

Besides the outrage over the individuals and institutions that tried to suppress the story, this incident has also sparked a broader discussion about the lack of adequate and timely sexual education for minors in Chinese schools. Liu Wenli (刘文利), an expert in children’s sexual education, argued on Weibo that both parents and schools play critical roles in teaching children about sex, their bodies, personal boundaries, and the risks of engaging with strangers online.

“Protecting children goes beyond shielding them from HPV infection,” Liu writes. “It means safeguarding them from all forms of harm. Sexual education is an essential part of this process, ensuring every child’s healthy and safe development.”

Many netizens discussing this case have expressed hope that the female doctor who brought the issue to light will not face repercussions or lose her job. They have praised her for exposing the incident and pursuing justice for the girl, alongside the efforts of those on Weibo who helped amplify the story.

The blogger who played a key role in exposing the story recently wrote: “I sure hope the authorities will give an award to the female doctor for reported this case in accordance with the law.” For some, the doctor is nothing short of a hero: “This doctor truly is my role model.”

By Manya Koetse, with contributions by Miranda Barnes

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Media

Hu Xijin’s Comeback to Weibo

After 90 days of silence, Hu Xijin is back on Weibo—but not everyone’s thrilled.

Published

4 months agoon

November 7, 2024

A SHORTER VERSION OF THIS ARTICLE WAS PART OF THE MOST RECENT WEIBO WATCH NEWSLETTER.

For nearly 100 days, since July 27, the well-known social and political commentator Hu Xijin (胡锡进) remained silent on Chinese social media. This was highly unusual for the columnist and former Global Times editor-in-chief, who typically posts multiple Weibo updates daily, along with regular updates on his X account and video commentaries. His Weibo account boasts over 24.8 million followers.

Various foreign media outlets speculated that his silence might be related to comments he previously made about the Third Plenum and Chinese economics, especially regarding China’s shift to treating public and private enterprises equally. But without any official statement, Chinese netizens were left to speculate about his whereabouts.

Most assumed he had, in some way, taken a “wrong” stance in his commentary on the economy and stock market, or perhaps on politically sensitive topics like the Suzhou stabbing of a Japanese student, which might have led to his being sidelined for a while. He certainly wouldn’t be the first prominent influencer or celebrity to disappear from social media and public view—when Alibaba’s Jack Ma seemed to have fallen out of favor with authorities, he went missing, sparking public concern.

After 90 days of absence, the most-searched phrases on Weibo tied to Hu Xijin’s name included:

胡锡进解封 “Hu Xijin ban lifted”

胡锡进微博解禁 “Hu Xijin’s Weibo account unblocked”

胡锡进禁言 “Hu Xijin silenced”

胡锡进跳楼 “Hu Xijin jumped off a building”

On October 31, Hu suddenly reappeared on Weibo with a post praising the newly opened Chaobai River Bridge, which connects Beijing to Dachang in Hebei—where Hu owns a home—significantly reducing travel time and making the more affordable Dachang area attractive to people from Beijing. The post received over 9,000 comments and 25,000 likes, with many welcoming back the old journalist. “You’re back!” and “Old Hu, I didn’t see you on Weibo for so long. Although I regularly curse your posts, I missed you,” were among the replies.

When Hu wrote about Trump’s win, the top comment read: “Old Trump is back, just like you!”

Not everyone, however, is thrilled to see Hu’s return. Blogger Bad Potato (@一个坏土豆) criticized Hu, claiming that with his frequent posts and shifting views, he likes to jump on trends and gauge public opinion—but is actually not very skilled at it, allegedly contributing to a toxic online environment.

Other bloggers have also taken issue with Hu’s tendency to contradict himself or backtrack on stances he takes in his posts.

Some have noted that while Hu has returned, his posts seem to lack “soul.” For instance, his recent two posts about Trump’s win were just one sentence each. Perhaps, now that his return is fresh, Hu is carefully treading the line on what to comment on—or not.

Nevertheless, a post he made on November 3rd sparked plenty of discussion. In it, Hu addressed the story of math ‘genius’ Jiang Ping (姜萍), the 17-year-old vocational school student who made it to the top 12 of the Alibaba Global Mathematics Competition earlier this year. As covered in our recent newsletter, the final results revealed that both Jiang and her teacher were disqualified for violating rules about collaborating with others.

In his post, Hu criticized the “Jiang Ping fever” (姜萍热) that had flooded social media following her initial qualification, as well as Jiang’s teacher Wang Runqiu (王润秋), who allegedly misled the underage Jiang into breaking the rules.

The post was somewhat controversial because Hu himself had previously stated that those who doubted Jiang’s sudden rise as a math talent and presumed her guilty of cheating were coming from a place of “darkness.” That post, from June 23 of this year, has since been deleted.

Despite the criticism, some appreciate Hu’s consistency in being inconsistent: “Hu Xijin remains the same Hu Xijin, always shifting with the tide.”

Hu has not directly addressed his absence from Weibo. Instead, he shared a photo of himself from 1978, when he joined the military. In that post, he reflected on his journey of growth, learning, and commitment to the country. Judging by his renewed frequency of posting, it seems he’s also recommitted to Weibo.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

What’s on Weibo Chapters

Subscribe

“Li Jingjing Was Here”: Chinese Netizens React to Rumors of “Chinese Soldiers” in Russia

How Ne Zha 2’s Shen Gongbao Became Known as the Ultimate “Small-Town Swot”

Beyond the Box Office: What’s Behind Ne Zha 2’s Success?

Ne Zha 2: Making Donghua Great Again

The Unstoppable Success of Ne Zha 2: Breaking Global Records and Sparking Debate on Chinese Social Media

Our Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Why Chinese Hit Movie “Her Story” is ‘Good Stuff’: Stirring Controversy and Celebrating Female Perspectives

Chiung Yao’s Suicide Farewell Letter: An English Translation

Breaking the Taboo: China’s Sanitary Pad Controversy Sparks Demand for Change

12-Year-Old Girl from Shandong Gets Infected with HPV: Viral Case Exposes Failures in Protecting Minors

Weibo Watch: Christmas in China Is Everywhere and Nowhere

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

Weibo Watch: China’s Online Feminism Is Everywhere

Story of Chinese Female MA Graduate Going Missing for 13 Years Sparks Online Storm

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight10 months ago

China Insight10 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music11 months ago

China Music11 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Insight12 months ago

China Insight12 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Digital9 months ago

China Digital9 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI