China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Top 10 China’s Most Popular Smartphone Brands & Models (May/June 2019)

These are the ten most popular smartphone brands and models in China right now.

Published

5 years agoon

There is one topic that is always buzzing on Chinese social media: the latest smartphone trends. This is a top 10 of the most popular Chinese smartphone brands and their hottest models of the moment.

In 2018, What’s on Weibo listed the top 10 most popular smartphone brands in China. With a smartphone market that is dynamic and rapidly changing, it’s time for an update to see which smartphones brands are currently most popular in the PRC.

Since 2017, we’ve seen various smartphone trends coming and going. Bezel-less devices, increasing the size of the screen, have gone from trend to norm. In the selfie era, the same holds true for high-performing front-facing cameras. More temporary trends have given way to more sophisticated gadget design. It’s all about superzoom cameras, full-view displays, pop-up selfie cameras, and let’s not forget about 5G.

One other major trend that is ongoing for the past years is that despite the popularity of Apple and Samsung, ‘made in China’ brands are dominating the smartphone and tablet market.

But the biggest trend now, more so than trendy and colorful design or smooth edges, is photography: the latest devices from different brands are now, more than ever, competing over who has the best (main) camera.

Looking at popularity charts on Baidu and Zol.com, leading IT portal website in China, the brands Oppo, Vivo, and Huawei are still the top popular smartphone brands in China. Huawei, Oppo, and Vivo were also the best-selling smartphones on the market in Q1 (Sohu), followed by Xiaomi, Apple, and Samsung.

Making an absolute top 10 of most popular smartphone brands in China at this moment is not so straightforward, however, since the rankings are different depending on the source and on which phone models are sold the most at a particular time.

The charts of leading e-commerce platforms JD.com and Suning, for example, are not exactly the same as Zol’s smartphone popularity rankings. We will stick to the Zol rankings for this article, looking at brands first and matching them with their most popular device models.

#10 Realme and the Realme X

Realme is a Shenzhen-based company that was established in 2018: it is the youngest smartphone brand in this list. Previously, it was a subbrand of OPPO but became independent in May of last year.

Realme has 1,2 million followers on Weibo. Realme is recently promoting its Realme X device, of which the hashtag page has a staggering 120 million views.

The Realme phone price starts at ¥1499 ($216) for the 4GB + 64GB storage variant. It has a a 6.53-inch full-HD+ (1080×2340 pixels) AMOLED screen, and features a 48-megapixel primary camera.

On social media, the Realme is mostly praised for its strong camera and friendly price.

#9 OnePlus (一加) and OnePlus7 Pro

OnePlus is a Shenzhen based Chinese smartphone manufacturer founded by Pete Lau and Carl Pei in December 2013. The company officially serves 32 countries and regions around the world as of January 2018.

The OnePlus 7 Pro of ¥4999 ($722) is currently listed as the number one popular smartphone by Zol.com; the brand itself is on the lower end of the top 10 most popular smartphone brands in China.

The 7 Pro device was called “one of the best Android phones you can buy” by AndroidCentral, on top of being “the best phone OnePlus has released to-date.”

The phone is big: it features a 6.67-inch display with a screen resolution of 1440 x 3120 pixels. It has fingerprint sensor, a 4000 mAh battery, and a rear 48MP + 16MP + 8MP camera.

#8 Meizu (魅族) and the Meizu 16s

Meizu is another Chinese homegrown brand, established by high school dropout Jack Wong (Huáng Zhāng 黄章) in 2003.

The Meizu device that is currently ranked in the top 10 hot-selling lists is the 16S that was released in April and is priced at ¥3198 ($462). The device has a 6.2 inch AMOLED screen (1080 x 2232 px). The main camera is a 48 MP, and the device is equipped with a 3600mAh battery.

The cheaper 16Xs (#魅族16Xs#) was a popular topic on social media on May 30, which is when it was launched.

#7 Xiaomi (小米) and the Redmi Note

Since the launch of its first smartphone in 2011, Beijing-brand Xiaomi has become one of the world’s largest smartphone makers. In the Zol rankings the brand is currently listed at number 7, in JD.com’s hot-selling lists, it’s ranked 3. The Redmi is actually a sub-brand of Xiaomi, but it’s still listed as Xiaomi in ranking lists such as that of JD.com.

The Xiaomi Redmi Note 7, Redmi K20, and Xiaomi 9 are all doing well, with the Redmi being the more popular device within the PRC. Techradar describes the Redmi Note 7 as a “great budget smartphone” with “stellar battery life.”

The Xiaomi Redmi Note 7 has a 6.3 inch (1080 x 2340) full-HD display (Full HD+) and a 12 MP main camera(the Redmi Note 7S has a 48 MP main camera). The cheapest models of ¥998 ($144) are among the lowest priced devices in this list.

#6 Apple (苹果) and the iPhone XR/XS Max

The position of Apple in China’s smartphone market has become a hot topic of discussion on social media recently in light of the rising China-US trade tensions. Although iPhone sales in China have indeed been dropping according to news reports, the iPhone XR and iPhone XS Max currently rank number 8 and number 10 most popular devices according to Zol at time of writing, with Apple ranking 6 in the top 10 smartphone brand charts. In the current list of best-selling smartphones on e-commerce site JD.com, the iPhone XR even ranks number one.

The iPhone XS Max is bigger than ever: it has a 6.5-inch OLED (2,688 x 1,242 pixels) screen whereas the XR has a 6.1-inch LCD (1,792 x 828 pixels). The camera of the XS Max has a dual 12-megapixel camera with wide-angle and telephoto. The XR has a single 12-megapixel wide-angle.

Some Chinese bloggers don’t understand why the iPhone is still so popular in China. Influential Weibo tech blogger Keji Xinyi (@科技新一) recently wrote: “The exterior of all Android flagship devices looks better than iPhone, they take better pictures too, why do girls still like the iPhone so much?”

Some of the popular answers include that people like iOS, that they prefer the “uncomplicated” use of the iPhone, and praise it for being “stable.”

With its ¥8399 ($1214) price tag, the iPhone XS Max is the most expensive phone around. The XR is currently priced at ¥5399 ($780).

#5 Honor (荣耀) and the Honor V20

Honor, established in 2013, is the budget-friendly sister of the Huawei brand. The company’s sub-brand has been doing very well over the past years. Honor focuses on great value for money.

The brand has over 21 million fans on Weibo. Honor targets younger consumers, not just with its relatively low prices, but also with its trendy designs, often offering phones in vibrant blue, pink and purple colors.

While the Honor brand currently ranks 5 on China’s nationwide smartphone brands popularity charts, its most popular device, the Honor V20, now ranks number 9 within smartphone device rankings. Another bestseller is the Honor Magic 2.

Priced at ¥2799 ($404), the V20 device is one of the cheaper ones in the popularity charts. It has a 6.40-inch display with a resolution of 1080×2310 pixels. Its rear camera is a 48-megapixel camera, with its selfie camera being a 25-megapixel one. It is available in colors Charm Sea Blue, Magic Night Black, Charm Red, Phantom Red, and Phantom Blue.

#4 Samsung (三星) and the Galaxy S10

Samsung currently is the most popular smartphone brand in the PRC that is not made-in-China. The brand seems to have been able to win back consumer’s trust after its previous problems with overheating and exploding batteries. In the first half of 2018, China actually replaced the US as the biggest market for Samsung.

The Galaxy S10 is the most popular Samsung device of this moment, and recent reports on bugs that allegedly come with a recent update have not seemed to impact its ranking.

The S10 has a 6.1-inch Super AMOLED QHD+ screen with 1440 x 3040-pixel display resolution. Like most devices on this list, its camera is good: a triple rear camera (12 MP x 12 MP x 16 MP) that can shoot panorama shots on ultra wide. The device has a dual-SIM tray/microSD card slot, and is water-resistant.

Price: ¥5999 ($867).

#3 Huawei (华为) and its P30 Series

In light of the China-US trade war, Huawei has been making international headlines recently. Judging from e-commerce ranking lists and ZOL.com popularity lists, Huawei’s popularity within the PRC seems to be unaffected by the recent consternation; if anything, it has only made the brand more popular within mainland China. Huawei remains to be one of China’s top smartphone brands.

The most popular device of the Huawei brand currently is the Huawei P30 Pro mobile, ranking fifth in Chinas most popular smartphone charts of this moment. The Huawei P30 is slightly less popular, ranked at number 8.

The P30 Pro features a Full HD+ OLED 6.47 inches display, an integrated fingerprint sensor in the display, with a screen resolution of 1080 x 2340 pixels. It has a 40MP + 16MP + 8MP camera that is the best part of the device, with an impressive zoom function:

The device has been called “one of the best and most unique phones” to be released this year, and is an absolute winner for its camera compared to the Samsung S10 or the iPhone XS Max. The Pro price is set at ¥5488 ($793), also making it one of the most expensive phones in the top lists of this moment.

#2 Vivo and its Vivo X27

Vivo is another Chinese brand that has gained worldwide success since it first entered the market in 2009. Its headquarters are based in Dongguan, Guangdong.

Vivo often cooperates with Chinese celebrities in its marketing campaigns, such as Chinese singer and actor Lu Han (born 1990) or Chinese actress Zhou Dongyu (born 1992), clearly targeting the post-90s consumer group.

The brand has over 37 million followers on its Weibo account, making it the most popular brand in terms of online fans.

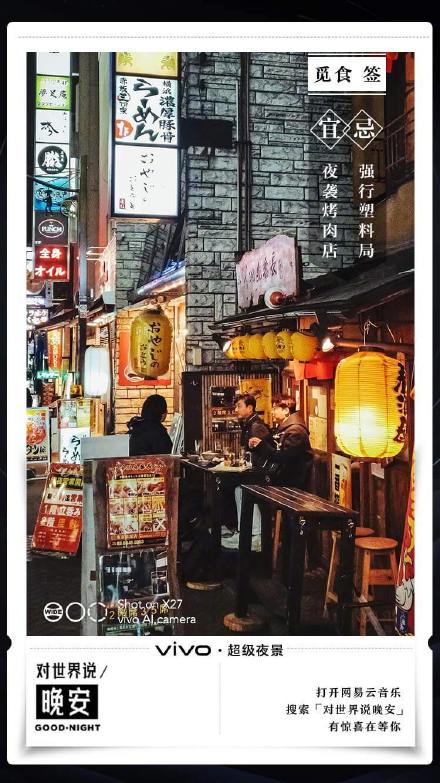

The Vivo X27 device was launched in China in March of 2019 and is specifically marketed as a “night photo” wonder tool.

The VivoX27 is a 6.39-inch dual-sim device with a super AMOLED screen. It has a 48 MP main camera and 12 MP selfie camera, and in-display fingerprint sensor.

The Vivo X27 Pro hashtag (#vivo X27 Pro#) has over 96 million views on Weibo at time of writing, with most netizens mostly praising the device for its ability to make good photos at night. The device is currently also ranked number one on Zol.com in the best mobile gaming device category.

Priced around ¥3598 ($520).

#1 Oppo and its OPPO Reno Series

2019 is the year of 5G, and OPPO Reno is ready for it. Oppo launched its latest 5G supported OPPO Reno smartphone in April of 2019 and has since been a hit on Chinese social media. The OPPO Reno hashtag (#OPPO全新Reno#) has a staggering 560 million views on the Sina Weibo platform at the time of writing, with the launch of the orange Reno becoming a trending topic in late May.

OPPO is a Guangdong-based brand that officially launched in 2004. The brand is known for targeting China’s young consumers with its trendy designs and smart celebrity marketing. In 2016, the brand hit international top smartphone lists and ranked as the number 4 smartphone brand globally.

OPPO currently has over 25 million fans on Weibo.

The OPPO Reno has a 6.4-inch AMOLED display, a 48-megapixel main camera, a wedge-shaped pop-up camera (16-megapixel front-facing), and in-display fingerprint scanner. Besides the standard Oppo Reno, there is also the OPPO Reno’s 10x Hybrid Zoom, and that model is mostly praised on Chinese social media for its photo quality under the OPPO Reno 10 X Zoom hashtag (#OPPOReno10倍变焦版#). Check the photos below of one Weibo user (@塔湾小魔王) trying out the zoom.

Price starting from: ¥3599 ($520).

Worth mentioning:

Some brands that did not make this top 10 list are still worth mentioning. One of them is Nubia (努比亚): Nubia may not be a very well-known brand outside of China, but in the PRC it’s been consistently hitting top brand lists. Nubia, owned by parent company ZTE, has been doing very well in China’s top-scoring smartphone lists since it was officially launched in 2015.

Other popular brands include Lenovo, ZTE, and Smartisan, Meitu: all Chinese companies.

“China has so many domestically produced smartphone,” Chinese tech blogger Keji Xinyi (@科技新一) recently wrote on Weibo: “Xiaomi, OPPO, vivo, OnePlus, Meizu, Lenovo, etc. etc. Why is it that if we’re talking about Chinese phones we’re always talking about Huawei?”

Among the hundreds of responses, many think Huawei is simply the best, with others saying it just has a very strong marketing campaign. Most people, however, agree that Chinese smartphone market has much more to offer than Huawei alone.

By Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2019 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Arts & Entertainment

Controversial Wanghong Livestreamers Are Becoming a Weibo Staple in China

‘Wanghong’ was a mark of online fame; now, it’s increasingly tied to controversy and scandal.

Published

3 weeks agoon

October 27, 2024

As livestreaming continues to gain popularity in China, so do the controversies surrounding the industry. Negative headlines involving high-profile livestreamers, as well as aspiring influencers hoping to make it big, frequently dominate Weibo’s trending topics.

These headlines usually revolve around China’s so-called wǎnghóng (网红) influencers. Wanghong is a shortened form of the phrase “internet celebrity” (wǎngluò hóngrén 网络红人). The term doesn’t just refer to internet personalities but also captures the viral nature of their influence—describing content or trends that gain rapid online attention and spread widely across social media.

Recently, an incident sparked debate over China’s wanghong livestreamers, focusing on Xiaohuxing (@小虎行), a streamer with around 60,000 followers on Douyin, who primarily posts evaluations of civil aviation services in China.

Xiaohuxing (@小虎行)

On October 15, 2024, at Shenzhen Bao’an International Airport, Xiaohuxing confronted a volunteer at the automated check-in counter, insisting she remove her mask while livestreaming the entire encounter. He was heard demanding, “What gives you the right to wear a mask? What gives you the right not to take it off?” and even attempted to forcibly remove her mask, challenging her to call the police.

During the livestream, the livestreamer confronted the woman on the right for wearing a facemask.

He also argued with a male traveler who tried to intervene. In the end, the airport’s security officers detained him. Shortly after the incident, a video of the livestream went viral on Weibo under various hashtags (e.g. #网红小虎行机场强迫志愿者摘口罩#) and attracted millions of views. The following day, Xiaohuxing’s Douyin account was banned, and all his videos were removed. The Shenzhen Public Security Bureau later announced that the account’s owner, identified as Wang, had been placed in administrative detention.

On October 13, just days before, another livestreaming controversy erupted at Guangzhou Baiyun International Airport. Malatang (@麻辣烫), a popular Douyin streamer with over a million followers, secretly filmed a young couple kissing and mocked them, continuing to film while passing through security—an area where filming is prohibited.

Her livestream quickly went viral, sparking discussions about unauthorized filming and misconduct among Chinese wanghong. In response, Malatang’s agent posted an apology video. However, the affected couple hired a lawyer and reported the incident to the police (#被百万粉丝网红偷拍当事人发声#). On October 17, Malatang’s Douyin account was banned, and her videos were removed.

Livestreamer Malatang making fun of the couple in the back at the airport.

In both cases, netizens uncovered additional examples of inappropriate behavior by Xiaohuxing and Malatang in past broadcasts. For example, Xiaohuxing was reportedly aggressive towards a flight attendant, demanding she kneel to serve him, while Malatang was criticized for scolding a delivery person who declined to interact with her on camera.

Comments on Weibo included, “They’ll do anything for traffic. Wanghong are getting a bad reputation because of people like this.” Another added, “It seems as if ‘wanghong’ has become a negative term now.”

Rising Scrutiny in China’s Wanghong Economy

Xiaohuxing and Malatang are far from isolated cases. Recently, many other wanghong livestreamers have also been caught up in negative news.

One such figure is Dong Yuhui (董宇辉), a former English teacher at New Oriental (新东方) who transitioned to livestreaming for East Buy (东方甄选), where he mixed education with e-commerce (read here). Dong gained significant popularity and boosted East Buy’s brand before leaving to start his own company. Recently, however, Dong faced backlash for inaccurate statements about Marie Curie during an October 9 livestream. He incorrectly claimed that Curie discovered uranium, invented the X-ray machine, and won the Nobel Prize in Literature, among other things.

Considering his public image as a knowledgeable “teacher” livestreamer, this incident sparked skepticism among viewers about his actual expertise. A related hashtag (#董宇辉称居里夫人获得诺贝尔文学奖#) garnered over 81 million views on Weibo. In addition to this criticism, Dong is also being questioned about potential false advertising, which is a major challenge for all livestreamers selling products during their streams.

Dong Yuhui (董宇辉) during one of his livestreams.

Another popular livestreamer, Dongbei Yujie (@东北雨姐), is currently also facing criticism over product quality and false advertising claims. Originally from Northeast China, Dongbei Yujie shares content focused on rural life in the region. Recently, her Douyin account, which boasts an impressive 22 million followers, was muted due to concerns over the quality of products she promoted, such as sweet potato noodles (which reportedly contained no sweet potato). Despite issuing public apologies—which have garnered over 160 million views under the hashtag “Dongbei Yujie Apologizes” (#东北雨姐道歉#)—the controversy has impacted her account and led to a penalty of 1.65 million yuan (approximately 231,900 USD).

From Dongbei Yujie’s apology video

Former top Douyin livestreamer Fengkuang Xiaoyangge (@疯狂小杨哥) is also facing a career downturn. Leading up to the 2024 Mid-Autumn Festival, he promoted Hong Kong Meicheng mooncakes in his livestreams, branding them as a high-end Hong Kong product. However, it was soon revealed that these mooncakes had no retail presence in Hong Kong and were primarily produced in Guangzhou and Foshan, sparking accusations of deceptive marketing. Due to this incident and previous cases of misleading advertising, his company came under investigation and was penalized. In just a few weeks, Fengkuang Xiaoyangge lost over 8.5 million followers (#小杨哥掉粉超850万#).

Fengkuang Xiaoyangge (@疯狂小杨哥) and the mooncake controversy.

It’s not only ecommerce livestreamers who are getting caught up in scandal. Recently, the influencer “Xiaoxiao Nuli Shenghuo” (@小小努力生活) and her mother were arrested for fabricating a tragic story – including abandonment, adoption, and hardships – to gain sympathy from over one million followers and earn money through donations and sales. They, and two others who helped them manage their account, were sentenced to ten days in prison for ‘false advertising.’

Wanghong Fame: Opportunity and Risk

China’s so-called ‘wanghong economy’ has surged in recent years, with countless content creators emerging across platforms like Douyin, Kuaishou, and Taobao Live. These platforms have transformed interactions between content creators and viewers and changed how products are marketed and sold.

For many aspiring influencers, becoming a livestreamer is the first step to building a presence in the streaming world. It serves as a gateway to attracting traffic and potentially monetizing their online influence.

However, before achieving widespread fame, some livestreamers resort to using outrageous or even offensive content to capture attention, even if it leads to criticism. For example, before his account was banned, Xiaohuxing set his comment section to allow only followers to comment, gaining 3,000 new followers after his controversial livestream at Shenzhen Airport went viral. Many speculated that some followers joined just to leave critical comments, but it nonetheless grew his following.

As livestreamers gain significant fame, they must exercise greater caution, as they often hold substantial influence over their audiences, making accuracy essential. Mistakes, whether intentional or not, can quickly erode trust, as seen in the example of the super popular Dong Yuhui, who faced backlash after his inaccurate comment about Marie Curie sparked public criticism.

China’s top makeup livestreamer, Li Jiaqi (李佳琦), experienced a similar reputational crisis in September last year. Responding dismissively to a viewer who commented on the high price of an eyebrow pencil, Li replied, “Have you received a raise after all these years? Have you worked hard enough?” Commentators pointed out that the pencil’s cost per gram was double that of gold at the time. Accused of “forgetting his roots” as a former humble salesman, Li lost one million Weibo followers in a day (read more here).

This meme shows that many viewers did not feel moved by Li’s apologetic tears after the eyepencil incident.

Despite the challenges and risks, becoming a wanghong remains an attractive career path for many. A mid-2023 Weibo survey on “Contemporary Employment Trends” showed that 61.6% of nearly 10,000 recent graduates were open to emerging professions like livestreaming, while 38.4% preferred more traditional career paths.

Taming the Wanghong Economy

In response to the increasing number of controversies and scandals brought by some wanghong livestreamers, Chinese authorities are implementing stricter regulations to monitor the livestreaming industry.

In 2021, China’s Propaganda Department and other authorities began emphasizing the societal influence of online influencers as role models. That year, the China Association of Performing Arts introduced the “Management Measures for the Warning and Return of Online Hosts” (网络主播警示与复出管理办法), which makes it challenging, if not impossible, for “canceled” celebrities to stage a comeback as livestreamers (read more).

The Regulation on the Implementation of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Consumer Rights and Interests (中华人民共和国消费者权益保护法实施条例), effective July 1, 2024, imposes stricter rules on livestream sales. It requires livestreams to disclose both the promoter and the product owner and mandates platforms to protect consumer rights. In cases of illegal activity, the platform, livestreaming room, and host are all held accountable. Violations may result in warnings, confiscation of illegal earnings, fines, business suspensions, or even the revocation of business licenses.

These regulations have created a more controlled “wanghong” economy, a marked shift from the earlier, more unregulated era of livestreaming. While some view these measures as restrictive, many commenters support the tighter oversight.

A well-known Kuaishou influencer, who collaborates with a person with dwarfism, recently faced backlash for sharing “vulgar content,” including videos where he kicks his collaborator (see video) or stages sensational scenes just for attention.

Most commenters welcome the recent wave of criticism and actions taken against such influencers, including Xiaohuxing and Dongbei Yujie, for their behavior. “It’s easy to become famous and make money like this,” commenters noted, adding, “It’s good to see the industry getting cleaned up.”

State media outlet People’s Daily echoed this sentiment in an October 21 commentary, stating, “No matter how many fans you have or how high your traffic is, legal lines must not be crossed. Those who cross the red line will ultimately pay the price.”

This article and recent incidents have sparked more online discussions about the kind of influencers needed in the livestreaming era. Many suggest that, beyond adhering to legal boundaries, celebrity livestreamers should demonstrate a higher moral standard and responsibility within this digital landscape. “We need positive energy, we need people who are authentic,” one Weibo user wrote.

Others, however, believe misbehaving “wanghong” livestreamers naturally face consequences: “They rise fast, but their popularity fades just as quickly.”

When asked, “What kind of influencers do we need?” one commenter responded, “We don’t need influencers at all.”

By Wendy Huang

Follow @whatsonweibo

Edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

China Books & Literature

Why Chinese Publishers Are Boycotting the 618 Shopping Festival

Bookworms love to get a good deal on books, but when the deals are too good, it can actually harm the publishing industry.

Published

6 months agoon

June 8, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

JD.com’s 618 shopping festival is driving down book prices to such an extent that it has prompted a boycott by Chinese publishers, who are concerned about the financial sustainability of their industry.

When June begins, promotional campaigns for China’s 618 Online Shopping Festival suddenly appear everywhere—it’s hard to ignore.

The 618 Festival is a product of China’s booming e-commerce culture. Taking place annually on June 18th, it is China’s largest mid-year shopping carnival. While Alibaba’s “Singles’ Day” shopping festival has been taking place on November 11th since 2009, the 618 Festival was launched by another Chinese e-commerce giant, JD.com (京东), to celebrate the company’s anniversary, boost its sales, and increase its brand value.

By now, other e-commerce platforms such as Taobao and Pinduoduo have joined the 618 Festival, and it has turned into another major nationwide shopping spree event.

For many book lovers in China, 618 has become the perfect opportunity to stock up on books. In previous years, e-commerce platforms like JD.com and Dangdang (当当) would roll out tempting offers during the festival, such as “300 RMB ($41) off for every 500 RMB ($69) spent” or “50 RMB ($7) off for every 100 RMB ($13.8) spent.”

Starting in May, about a month before 618, the largest bookworm community group on the Douban platform, nicknamed “Buying Like Landsliding, Reading Like Silk Spinning” (买书如山倒,看书如抽丝), would start buzzing with activity, discussing book sales, comparing shopping lists, or sharing views about different issues.

Social media users share lists of which books to buy during the 618 shopping festivities.

This year, however, the mood within the group was different. Many members posted that before the 618 season began, books from various publishers were suddenly taken down from e-commerce platforms, disappearing from their online shopping carts. This unusual occurrence sparked discussions among book lovers, with speculations arising about a potential conflict between Chinese publishers and e-commerce platforms.

A joint statement posted in May provided clarity. According to Chinese media outlet The Paper (@澎湃新闻), eight publishers in Beijing and the Shanghai Publishing and Distribution Association, which represent 46 publishing units in Shanghai, issued a statement indicating they refuse to participate in this year’s 618 promotional campaign as proposed by JD.com.

The collective industry boycott has a clear motivation: during JD’s 618 promotional campaign, which offers all books at steep discounts (e.g., 60-70% off) for eight days, publishers lose money on each book sold. Meanwhile, JD.com continues to profit by forcing publishers to sell books at significantly reduced prices (e.g., 80% off). For many publishers, it is simply not sustainable to sell books at 20% of the original price.

One person who has openly spoken out against JD.com’s practices is Shen Haobo (沈浩波), founder and CEO of Chinese book publisher Motie Group (磨铁集团). Shen shared a post on WeChat Moments on May 31st, stating that Motie has completely stopped shipping to JD.com as it opposes the company’s low-price promotions. Shen said it felt like JD.com is “repeatedly rubbing our faces into the ground.”

Nevertheless, many netizens expressed confusion over the situation. Under the hashtag topic “Multiple Publishers Are Boycotting the 618 Book Promotions” (#多家出版社抵制618图书大促#), people complained about the relatively high cost of physical books.

With a single legitimate copy often costing 50-60 RMB ($7-$8.3), and children’s books often costing much more, many Chinese readers can only afford to buy books during big sales. They question the justification for these rising prices, as books used to be much more affordable.

Book blogger TaoLangGe (@陶朗歌) argues that for ordinary readers in China, the removal of discounted books is not good news. As consumers, most people are not concerned with the “life and death of the publishing industry” and naturally prefer cheaper books.

However, industry insiders argue that a “price war” on books may not truly benefit buyers in the end, as it is actually driving up the prices as a forced response to the frequent discount promotions by e-commerce platforms.

China News (@中国新闻网) interviewed publisher San Shi (三石), who noted that people’s expectations of book prices can be easily influenced by promotional activities, leading to a subconscious belief that purchasing books at such low prices is normal. Publishers, therefore, feel compelled to reduce costs and adopt price competition to attract buyers. However, the space for cost reduction in paper and printing is limited.

Eventually, this pressure could affect the quality and layout of books, including their binding, design, and editing. In the long run, if a vicious cycle develops, it would be detrimental to the production and publication of high-quality books, ultimately disappointing book lovers who will struggle to find the books they want, in the format they prefer.

This debate temporarily resolved with JD.com’s compromise. According to The Paper, JD.com has started to abandon its previous strategy of offering extreme discounts across all book categories. Publishers now have a certain degree of autonomy, able to decide the types of books and discount rates for platform promotions.

While most previously delisted books have returned for sale, JD.com’s silence on their official social media channels leaves people worried about the future of China’s publishing industry in an era dominated by e-commerce platforms, especially at a time when online shops and livestreamers keep competing over who has the best book deals, hyping up promotional campaigns like ‘9.9 RMB ($1.4) per book with free shipping’ to ‘1 RMB ($0.15) books.’

This year’s developments surrounding the publishing industry and 618 has led to some discussions that have created more awareness among Chinese consumers about the true price of books. “I was planning to bulk buy books this year,” one commenter wrote: “But then I looked at my bookshelf and saw that some of last year’s books haven’t even been unwrapped yet.”

Another commenter wrote: “Although I’m just an ordinary reader, I still feel very sad about this situation. It’s reasonable to say that lower prices are good for readers, but what I see is an unfavorable outlook for publishers and the book market. If this continues, no one will want to work in this industry, and for readers who do not like e-books and only prefer physical books, this is definitely not a good thing at all!”

By Ruixin Zhang, edited with further input by Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

The ‘Cycling to Kaifeng’ Trend: How It Started, How It’s Going

Hu Xijin’s Comeback to Weibo

Weibo Watch: “Comrade Trump Returns to the Palace”

The Price of Writing Smut: Inside China’s Crackdown on Erotic Fiction

Controversial Wanghong Livestreamers Are Becoming a Weibo Staple in China

“Land Rover Woman” Sparks Outrage: Qingdao Road Rage Incident Goes Viral in China

Weibo Watch: The Land Rover Woman Controversy Explained

Fired After Pregnancy Announcement: Court Case Involving Pregnant Employee Sparks Online Debate

Weibo Watch: Going the Wrong Way

The Rising Influence of Fandom Culture in Chinese Table Tennis

China at the 2024 Paralympics: Golds, Champions, and Trending Moments

Hidden Hotel Cameras in Shijiazhuang: Controversy and Growing Distrust

Weibo Watch: Small Earthquakes in Wuhan

Death of Chinese Female Motorcycle Influencer ‘Shigao ProMax’ Sparks Debate on Risky Rides for Online Attention

Why the “人人人人景点人人人人” Hashtag is Trending Again on Chinese Social Media

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight7 months ago

China Insight7 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music8 months ago

China Music8 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Insight12 months ago

China Insight12 months agoThe Story of Li Jun & Liang Liang: How the Challenges of an Ordinary Chinese Couple Captivated China’s Internet