China Arts & Entertainment

Top 30 Classic TV Dramas in China: The Best Chinese Series of All Time

This year marks 60 years of Chinese TV drama. These are the best Chinese TV dramas of all time.

Published

6 years agoon

PREMIUM CONTENT ARTICLE

First published

They might have aired 30 years ago, but some TV dramas just never get old. We have listed the greatest classic Chinese TV dramas of all time, that, either because of their high-production value or historic ratings, are still talked about today. A special overview by What’s on Weibo, as China celebrates 60 years of TV drama this year.

This year marks the 60th anniversary of Chinese TV drama since the airing of the very first (one-episode) drama A Mouthful of Vegetable Pancakes (一口菜饼子) in 1958 – the same year in which the very first Chinese television station started broadcasting (Bai 2007, 77).

The drama, live broadcasted by Beijing Television, sent out a message of frugality, as one young girl warns her sister not to waste food by remembering her of their difficult past and brave mother, who died of hunger while even refusing to eat the last bit of food, a vegetable pancake.

A Mouthful of Pancakes aired in 1958.

Much has changed within those sixty years. After a time when the production of TV dramas practically came to a standstill during the Cultural Revolution, the late 1970s and early 1980s saw a boom in the popularity of television dramas, along with a spike in households that owned their own TV. From 1980 to 1990, the number of household television sets in China increased from 5 to 160 million (Wang & Singhal 1992, 177).

Since the 1980s, mainland China has gone from a country where most television dramas were imported from outside the country, to one that has the most thriving domestic TV drama industry in the world.

Some TV dramas in this list have become classics through time, some are fairly new but have already become classics within their genre.

This list has been fully compiled by What’s on Weibo, based on popularity charts on Chinese search engine Sogou’s top tv drama listings of all time, together with ranking on Douban, a big Chinese social networking service and influential media review website, and also based on academic sources that note the importance of some of these TV classics.*1 We will list a recommendation list of relevant books at the end of this article.

Most of these series will have links redirecting to available versions on Youtube or elsewhere – unless written otherwise, they do not have English subtitles. Please share English subtitled versions in the comment section if you found them, we’ll add them to the list.

This article is focused on those classics that have been important for the TV drama industry and audiences of mainland China. Although several of them were produced in Hong Kong or Taiwan, the majority is from the PRC. These dramas are listed in chronological order of appearance, not listed based on rankings.

Here we go!

#1 The Bund / The Shanghai Bund (上海滩)

Year: 1980

Episodes: 25

Genre: Action

Produced in Hong Kong

Noteworthy: “The Godfather of the East”

This TV drama became such a sensation across China in 1980, that it also became known as the Chinese equivalent to the classic Godfather series.

Actors Angie Chiu and Chow Yun-Fat star in this Hong Kong drama, that is set in the underworld society of 1920s Shanghai, and revolves around the tumultuous love story between Feng Chengcheng and Xu Wenqiang.

The series has become such a classic that it still plays an important role in popular culture of China today, with newer films and TV dramas also being based on the original series (the 2007 mainland China TV series Shanghai Bund, for example, is a remake of the 1980 original). If you ever go to karaoke, you’re probably already familiar with the shows’ famous theme song ‘Seung Hoi Tan’ (上海滩) by Frances Yip (see here).

#2 Eighteen Years in the Enemy’s Camp (敌营十八年)

Year: 1981

Episodes: 9

Genre: War Drama

Watch the first episode here on Youtube.

Noteworthy: “The first TV drama produced by CCTV”

Eighteen Years in the Enemy’s Camp is somewhat of a cult classic in China. Despite the fact that the TV drama itself was somewhat poorly produced, it still gets high ratings on sites such as QQ Video or Douban today.

At a time when the Chinese TV drama market was still dominated by imported television series (from Hong Kong, US, and other places), Eighteen Years in the Enemy’s Camp was the first drama series made by CCTV (Bai 2007, 80), directed by Wang Fulin (王扶林) and Du Yu (都郁).

The story revolves around the Communist Party member Jiang Bo (江波), who spends 18 years undercover in the “tiger’s den” (虎穴), the enemy’s camp, as a National Army officer, thwarting the Nationalists’ plans until the 1949 victory of the Communists.

Fun fact by Ruoyun Bai (see references): despite the fact that the entire show is about the Nationalists Army, not a single Nationalist Army uniform could be found for the cast. The uniforms that were used, were not up to par: the main character had to leave his coat’s collar unbuttoned because it was too tight, and always has his hat in his hands because it was actually too small to fit his head (2007, 80-81).

#3 Ji Gong (济公)

Year: 1985

Episodes: 12

Genre: Fantasy

Directed by Zhang Ge (张戈)

All episodes can be watched here on YouTube.

Noteworthy: “Influenced by Charlie Chaplin”

This popular TV series is centered around Ji Gong, the folk hero and Chan Buddhist monk who lived in the Southern Song and, according to legend, had supernatural powers and spent his whole life helping the poor.

The main role is played by renowned Chinese artist and mime master You Benchang (游本昌). In an interview with CRI, the actor once said that he was heavily influenced by his idol Charlie Chaplin for this role, sometimes even imitating some of Chaplin’s gestures.

#4 Chronicles of The Shadow Swordsman (萍踪侠影)

Year: 1985

Episodes: 25

Genre: Wuxia/Martial

Directed by: Wang Xinwei (王心慰)

Produced in Hong Kong

Episodes available on Youtube here.

Noteworthy: “Perfect Chemistry between Leading Actors”

This classic TV drama features actors Damian Lau as Zhang Danfeng and Michelle Yim as Yun Lei, whom are often praised by drama lovers for their perfect chemistry in these series. Of the many adaptations there are of Liang Yusheng’s wuxia novel Chronicles of The Shadow Swordsman, many say this is their favorite.

#5 New Star (新星)

Year: 1986

Episodes: 12

Directed by: Li Xin (李新)

Noteworthy: “A drama anyone over 50 will remember”

This CCTV mini-drama, based on the novel by Ke Yunlu (柯云路), tells the story of a young Party secretary fighting against corruption. Before Heaven Above (later in this list), it is thus one of the very first dramas to focus on corruption as a theme, and it also caused a buzz at the time for doing so – most people over 50 in China today will probably remember this TV series today.

#6 Journey to the West (西游记)

Year: 1986

Episodes: 25 for season one, 16 episodes for season 2

Directed by Yang Jie (杨洁)

Watch on Youtube (with English subtitles!) here.

Noteworthy: “Shot with one camera”

This is an all-time favorite TV series in China that is still rated with a 9.5 on the TV drama database of search engine Sogou. It has been an instant classic from the moment it was first broadcasted by CCTV in October of 1986.

Journey to the West (Xīyóu jì 西游记), published in the 16th century (Ming dynasty), is one of the most important classical works in the history of Chinese literature, and tells the story of the long journey to India of the Tang Monk Xuánzàng, who is on a mission to obtain Buddhist sutras. He is joined by three disciples, the pig demon Zhū Bājiè, the river demon Shā Wùjìng, and Sūn Wùkōng, who is better known as the Monkey King in the West.

The Monkey in the series is played by Zhang Jinlai (章金莱), also known as Liu Xiao Ling Tong, who recently recalled in an CGTN article that: “it was 30 years ago and we’d got only one camera. We walked around China’s picturesque areas and took 17 years to make 41 episodes. 17 years equals Monk Xuanzang’s pilgrimage for the Buddhist scriptures.”

#7 “The Dream of Red Chambers” (红楼梦)

Year: 1987

Episodes: 36

Directed by: Wang Fulin (王扶林)

Watch with English subtitles on YouTube here.

Noteworthy: “The first entry of Chinese tv drama into the global market”

Even today, this CCTV TV series from 1987 is still rated as one of the best Chinese television series of all time on Sogou, where viewers rate it with a 9.6.

Like other series in this list, this is an adaptation from a classic literary work; Dream of the Red Chamber (Hónglóumèng), one of China’s Four Great Classical Novels, which was written by Cao Xueqin in the mid-18th century during the Qing.

In June of 1987, this TV drama became the first Chinese television series to be exported to Malaysia and West-Germany, making it “the first entry of Chinese tv drama into the global market” (Hong, 32).

#8 The Investiture of the Gods (封神榜)

Year: 1990

Episodes: 36

Genre: Fantasy/Costume Drama

Directed by: Guo Xinling (郭信玲)

The first episode is available on YouTube here.

Noteworthy: “Based on the classical novel Fengshen Yanyi“

This TV series is based on the classical novel Fēngshén Yǎnyì (封神演義), also known as Investiture of the Gods or Creation of the Gods), written by Xu Zhonglin and Lu Xixing. Famous Chinese actor and painter Lan Tianye (蓝天野) was praised for his role as Jiang Ziya in this drama.

The (female) director Guo Xinling (1936-2012) was a Party member who worked on many televised works during her career.

Just as many others of the series in this list based on classic novels, there are remakes of these series in recent times.

#9 Yearnings / Kewang (渴望)

Year: 1990

Episodes: 50

Genre: Family drama

Directed by Lu Xiaowei (鲁晓威) and Zhao Baoguang (赵宝刚).

Noteworthy: “China’s first soap opera – a national craze”

Yearnings is also known as China’s real first soap opera, which caused a sensation across the nation – sales of TV sets surged, and streets were empty when it aired.

The story’s time spans from the Cultural Revolution until the 1980s reform period. The series, set in Beijing, tells the story of working-class woman Liu Huifang and her unlikely marriage to the middle-class Wang Husheng, a university graduate who comes from a family of intellectuals. When Huifang finds an abandoned baby, she adopts it against the will of her husband.

As the first TV series that focused on the hopes and dreams of ordinary Chinese people, the success of Yearnings was unprecedented, and it formed the beginning of Chinese television drama as we know it today.

#10 River of Gratitude (江湖恩仇录)

Year: 1989

Episodes: 20

Genre: Wuxia/Martial

Directed by: Mao Yuqin (毛玉勤)

Watch first episode on Youtube here

Noteworthy: “A true classic – it’s nostalgia!”

One of the main stars in this series is actress and producer Wenying Dongfang (东方闻樱), who also starred in A Dream in Red Mansion (1987).

By commenters on Douban, this series is described as a “cult classic.” Although some say the quality of the series, now, looking back, is somewhat substandard or silly, according to many, the nostalgia of seeing it in the early 1990s and being excited about it seems to play a major factor in why people still grade this one as a true classic – it’s nostalgia!

#11 Wan Chun (婉君)

Year: 1990

Episodes: 18

Produced in Taiwan

Noteworthy: “The first Taiwanese TV series filmed in mainland China”

Wan Chun is a 1990 Taiwanese television series about a girl named Wan Chun and her three adoptive brothers, that is based on the 1964 novel “Wan-chun’s Three Loves” (追尋) by Taiwanese writer and producer Chiung Yao, and which is set in Republican era Beijing.

This is the first cross-strait co-production, as a Taiwanese TV series filmed in mainland China. Wan Chun was followed up by the 1990 Taiwanese television drama series Mute Wife based on Chiung Yao’s 1965 novelette of the same name.

#12 The Legend of Qianlong (戏说乾隆)

Year: 1991

Episodes: 41

Genre: Imperial drama

Produced in Taiwan (Taiwan-mainland co-production)

Watch on Youtube here

Noteworthy: “The beginning of a genre”

In today’s TV drama environment of China, dramas that focus on life during the imperial era are ubiquitous, with titles from the Imperial Doctress to Story of Yanxi Palace being everywhere.

But when this drama aired in the early 1990s, it was something quite new. The Legend of Qianlong, also known with the English translation A Fanciful Account of Qianlong, tells the (fictional) stories of the Emperor Qianlong’s Tours of Southern China.

It was the beginning of a drama genre that turned out to be hugely popular, with many new television series focusing on emperors and empresses in their youth or their tumultuous lives during the height of their power (Barme 2012, 33). Perhaps, this 1991 series will always be a classic just because it was one of the first within its genre.

#13 The Legend of the White Snake (新白娘子传奇)

Year: 1992

Episodes: 50

Genre: Fantasy

Produced in Taiwan

Noteworthy: “One of the most replayed TV series”

As many of the classics in this list, this hit TV series is also based on a folk legend, namely that of Madame White Snakee, a mythical snake-like spirit who strives to be human, which is a source for many major Chinese operas, films.

The 1992 TV series stars Angie Chiu and Cecilia Yip. In 2016, it was still one of the most replayed TV series. Even on IMDB, it is rated with an 8.2.

#14 Beijinger in New York (北京人在纽约)

Year: 1993

Episodes: 21

Watch: YouTube

Buy novel (in English): Beijinger in New York

Noteworthy: “The first Chinese-language TV show to be shot in the United States”

The TV series Beijinger in New York, also known as A Native of Beijing in New York, based on the novel by Glen Cao (Cao Guilin), was a hit when it was first broadcasted broadcast nightly on CCTV and watched by millions of Chinese.

The story follows the immigrant life of cello player and Beijinger Wang Qiming (王起明), who arrives in New York in 1980 together with his wife, and begins working as a dishwasher the next day.

The TV series marks a first in several aspects. It was the first Chinese-language TV show to be shot in the United States, but it was also the first time ever for the production of a Chinese TV drama that a bank loan was used in order to make it possible (Bai 2007, 83); in other words, it also marks the start of a more commercialized TV drama environment. FYI: the bank loan that was used was a total of US$1.3 million.

#15 I Love My Family (我爱我家)

Year: 1993

Genre: Comedy

Episodes: 120

Directed by Ying Da (英达) et al

First episodes on Youtube here.

Noteworthy: “First Mandarin-language sitcom”

I Love My Family (Wǒ ài wǒjiā) is one of China’s first popular sitcoms, and the first Mandarin-language and multi-camera sitcom, that aired from 1993 to 1994. It has since been rerun on local channels countless of times.

One of the show’s central stars is Wen Xingyu (文兴宇), who was a popular comedian and director in mainland China.

At the time of I Love My Family, sitcoms were mostly characterized by their low production cost; three episodes were made within five working days (Di 2008, 122).

#16 Justice Pao (包青天)

Year: 1993

Episodes: 236

Genre: Historical drama

Produced in Taiwan

Some episodes on Youtube here.

Noteworthy: “From 15 to 236 episodes”

This series is themed around Bao Zheng (包拯), a government official who lived during China’s Song Dynasty, from 999 to 1062, and who was known for his extreme honesty and uprightness. Award-winning Taiwanese actor Jin Chao-chun (金超群) plays this role.

The series was originally scheduled for just 15 episodes, but was received so well when it aired on Chinese Television System, that it was eventually expanded to 236 episodes.

The story of Justice Bao is still a recurring topic in the popular culture of mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. There was the 2008 Chinese series Justice Bao, and the 2010 New Justice Bao, that also starred Jin Chao-chun.

#17 Romance of the Three Kingdoms (三国演义)

Year: 1994

Episodes: 84

Genre: Historical drama

Directed by: Wang Fulin (王扶林)

Buy original novel here: The Romance of the Three Kingdoms

Some episodes available with English subtitles here.

Noteworthy: “400,000 people involved in the production”

This is another classic TV series produced by the CCTV, and that is also adapted from a classical novel (same title, written by Luo Guanzhong). Its director, Wang Fulin (王扶林), also directed the CCTV’s first TV drama Eighteen Years in the Enemy’s Camp, and A Dream of Red Mansions.

The production of Romance of the Three Kingdoms is especially noteworthy because the productions costs broke all kinds of records at the time; the production of the 84 one-hour episodes took four years, total costs were over 170 million RMB (±US$25 million), and around 400,000 people were involved – the larghest number of people involved in a production in the history of Chinese television. THe show has been watched by some 1,2 billion people around the world (Hongb 2007, 127).

#18 Heaven’s Above (苍天在上)

Year: 1995

Episodes: 17

Genre: Corruption drama (or ‘anti-corruption drama’ 反腐剧)

Directed by: Zhou Huan (周寰)

Noteworthy: “First drama about high-level official corruption”

In late 1995, the CCTV drama Heaven Above (Cāngtiān zài shàng) debuted on Chinese TV as the first TV series about high-level official corruption in the PRC.

It would certainly not be the last, as ‘corruption dramas’ became wildly popular – it is the entire focus of the 2014 book Staging Corruption by scholar Ruoyun Bai.

#19 Foreign Babes in Beijing (洋妞在北京)

Year: 1995

Genre: Urban drama

Episodes: 20

Noteworthy: “Foreign women in Chinese dramas”

Foreign Babes in Beijing (Yáng niū zài Běijīng) was one of the new kinds of dramas that featured foreigners in China. This series focues on two Chinese men and two American women, of which one seduces one of the Chinese (married) men. The show was a big hit in the mid-1990s.

One of the show’s actresses, Rachel Dewoskin, later wrote the recommended book Foreign Babes in Beijing: Behind the Scenes of a New China about her experiences of playing in the show and her life in China at the time.

#20 My Dear Motherland (我亲爱的祖国)

Year: 1999

Episodes: 21

Genre: History/War

Directed by: Liu Yiran (刘毅然)

Watch on Billibilli here, QQ, or on Youtube.

Noteworthy: “Rated with a 9.1”

This 1999 series is still rated with a 9.1 on Douban today. The series tells the experiences and hardships of three generations of Chinese intellectuals during the tumultuous (war)history of China’s 20th century, starting during the May Fourth Movement in 1919.

Chen Jianbin (陈建斌) is one of the famous actors starring in this TV drama as Fang Xuetong.

#21 Yongzheng’s Dynasty (雍正王朝)

Year: 1999

Episodes: 44

Genre: History/Costume

Noteworthy: “Qing drama as export product”

Yongzheng Dynasty is one of many so-called “Qing dramas” – TV dramas that focus on palace life during the 1644-1911 Qing Dynasty. According to scholar Zhu (2008), one of the reasons that dynasty dramas such as these became so enormously popular in mainland China is that (1) certain social and political issues can be discussed in the shape of stories and settings that are very much removed from modern-day China, allowing for more relaxed censorship policies on storylines and dialogues, and (2) that the reconstruction of “history” allows room for artistic interventions (22).

This epic TV drama was loosely based on historical events in the reigns of the Kangxi and Yongzheng Emperors, and became one of the most watched television series in mainland China of the 1990s. Also outside of China the show became very popular, making the so-called ‘Qing dramas’ an export product.

#22 Towards the Republic (走向共和)

Year: 2003

Episodes: 59 (one hour per episode)

Genre: Historical drama

Directed by: Zhang Li (张黎)

Watch on Youtube , buy on Amazon with English subtitles.

Noteworthy: “59 hours of historical drama”

This is one of the most important TV series in this list. On Sogou ratings, Towards the Republic, which is also known as For the Sake of the Republic (Zǒuxiàng gònghé), is one of netizens’ top all-time favorite series, rated with a 9.7.

The CCTV TV drama tells the story of the historical events in China from 1890 to 1917 – the time during which the Qing Dynasty collapsed, and the Republic of China (1912-1949) was founded. Important historical events such as the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), the Hundred Days’ Reform (1898), the Boxer Rebellion (1900) and the Xinhai Revolution (1911) are all featured in this epic drama, that mainly focuses on the lives of Li Hongzhang (Chinese general in late Qing), Empress Dowager Cixi, Sun Yat-Sen, and Yuan Shikai.

The historical drama was not without controversy, and some parts of it have been censored in mainland China. The original series had 60 episodes, which was later brought down to 59. The TV drama has also been a fruitful topic for scholars for its representation of history. In the 2007 book Representing History in Chinese Media: The TV Drama Zou Xiang Gonghe (Towards the Republic) by Gotelind Mueller, the entire series is analyzed in how history is portrayed and narrated.

#23 Crimson Romance (血色浪漫)

Year: 2004

Episodes: 32

Genre Youth drama

Directed by: Teng Wenji (滕文骥)

Watch on Youtube here.

Noteworthy: “Romantizing the Cultural Revolution”

There are almost 40,000 netizens ranking this 2004 TV drama on Douban, where it scores a 8.7.

The TV drama, which is also known as Romantic Life in English, dramatizes memories of the Cultural Revolution, focusing on a group of friends, their hopes and dreams, and their romantic life. It is set in Beijing in the late period of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976).

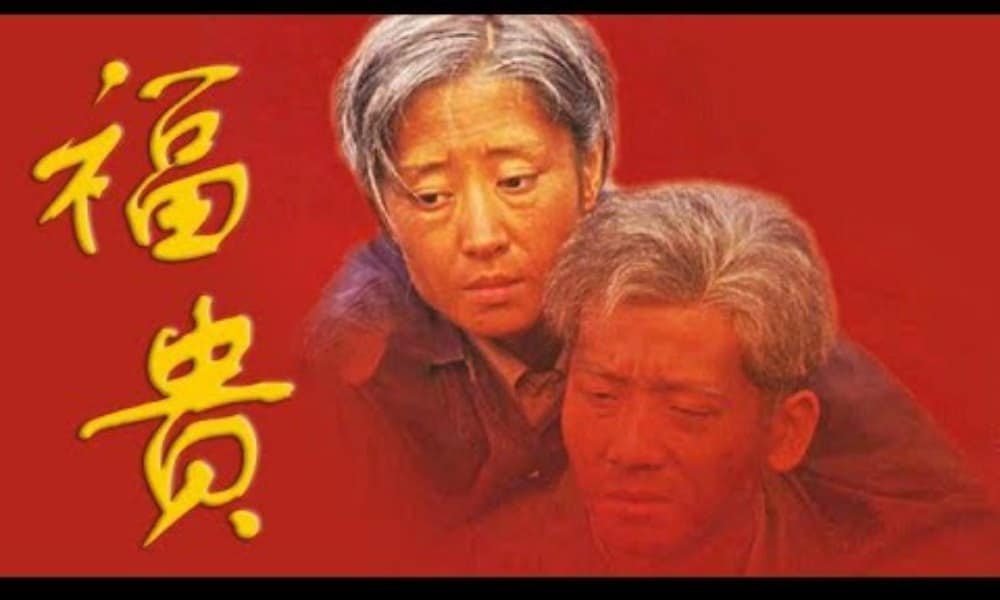

#24 Fu Gui (福贵)

Year: 2005

Episodes: 33

Genre: Family drama

Directed by Zhu Zheng (朱正)

Original novel: To Live: A Novel

Watch on Youtube.

Noteworthy: “Based on the novel To Live“

Chuang Chen (陈创), Liu Mintao (刘敏涛), and Li Ding (李丁) star in this family drama, which is ranked with a 9.4 on Sogou, and 4,5 stars or a 9,4 on Douban (more than 5500 voters).

The drama is based on the 1993 novel by Yu Hua (余华) To Live (活着), which focuses on the struggles of the son of a wealthy land-owner, Xu Fugui, amidst the tumultuous times of the Chinese Revolution. The story became well-known by the movie of the same title by Zhang Yimou, which became an international success.

#25 Ming Dynasty in 1566 (大明王朝1566)

Year: 2007

Episodes: 46

Genre: Historical drama

Directed by: Zhang Li (张黎)

Available with English subtitles on Youtube

Noteworthy: “Scoring a 9.7 on Douban, rated by 55,000 users”

Ming Dynasty in 1566 (Dàmíng wángcháo), starring Chinese actor Chen Baoguo (陈宝国), is a Chinese television series based on historical events during the reign of the Jiajing Emperor (1507-1567) of the Ming dynasty. It was first broadcast on Hunan TV in China in 2007.

On Douban, more than 55000 people have reviewed this movie at time of writing, coming up with a score of 9.7, one of the highest in this list. The drama was also broadcasted in other countries, such as South Korea.

#26 Dwelling Narrowness (蜗居)

Year: 2009

Episodes: 35

Genre: Urban Drama

Directed by: Teng Huatao (滕华涛)

Watch on Youtube here.

Noteworthy: “Focusing on China’s urban real estate bubble”

Also known as Snail House, this TV drama was all the rage back in 2009 for its focus on the crazy housing market in urban China and the lives of ordinary Chinese who are struggling to survive in the city while living in small spaces. Dwelling Narrowness, based on a novel by the same name, tells the story of two sisters with very different lifestyles who are looking to find a home in Shanghai (or actually, the fictional city of Jiangzhou, that basically represents Shanghai), and improve their quality of life, each in their own way.

The real estate bubble is a major theme throughout these series, and the TV drama was much-discussed within the frame of Chinese urban dwellers becoming “house slaves” (房奴). In the year of its broadcast, Wall Street Journal featured an article dedicated to the series and the discussions it triggered online.

#27 The Red (红色)

Year: 2014

Episodes: 48

Genre: War drama

Directed by Yang Lei (杨磊)

Noteworthy: “Patriotism as its key theme”

War drama The Red (Hóngsè) receives a 9.2 on Sogou, showing its success over the last four years.

Edward Zhang (Zhang Luyi 张鲁一) stars in this drama as an ordinary worker in Shanghai who gets caught up in underground circles at the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War, and unexpectedly becomes part of a decisive moment in Chinese modern history. Perhaps unsurprinsginly, ‘Patriotism’ is a key theme throughout The Red.

#28 Moral Peanuts – Final Season (毛骗 终结篇)

Year: 2015

Episodes: 10 (in this season)

Genre: Crime/Suspense

Directed by: Li Hongchou (李洪绸)

Watch on Youtube here.

Noteworthy: “A gang of friends who con people out of their money”

Rated with a 9.6 on Sogou and a 9.6 by more than 26,000 people on Douban, this TV drama has already become somewhat of a classic in the few years since its airing.

Moral Peanuts is a multiple season series (started in 2010), that follows a gang of five young friends who live together and earn their living in a fraudulent way. The series is characterized by its cliffhanger endings and its ‘grey’ portrayals of its characters.

#29 In the Name of the People (人民的名义)

Year: 2017

Episodes: 55

Genre: Corruption drama

Directed by: Li Lu

Available with English subtitles here.

Noteworthy: “The Chinese ‘House of Cards'”

In the Name of the People is a 2017 highly popular Chinese TV drama series based on the web novel of the same name by Zhou Meisen (周梅森). Its plot revolves around a prosecutor’s efforts to unearth corruption in a present-day fictional Chinese city by the name of Jingzhou.

In 2017, this TV drama became a true craze on Chinese social media and received a lot of coverage in (international) media for being comparable to the American political drama House of Cards. The BBC described it as “the latest piece of propaganda aimed at portraying the government’s victory in its anti-corruption campaign.”

#30 White Deer Plain (白鹿原)

Year: 2017

Genre: Contemporary historical drama

Episodes: 85

Directed by: Liu Jin (刘进)

WAtch with English subs at New Asian TV here.

Noteworthy: “The epic TV drama took nearly 17 years to prepare and produce “

This TV drama has consistently been ranking number one in Baidu’s and Weibo’s popular drama charts last year, and is now ranked with an 8.8 score on sites such as Douban. Although it is somewhat tricky to call such a present-day drama a ‘classic’, we’ll take the chance.

White Deer Plain is based on the award-winning Chinese literary classic by Chen Zhongshi (陈忠实) from 1993. The preparation and production of this series reportedly took a staggering 17 years and a budget of 230 million yuan (US$33.39 million).

The success of the novel this TV drama is based on, has previously been compared to that of One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez. White Deer Plain follows the stories of people from several generations living on the ‘White Deer Plain,’ or North China Plain in Shaanxi province, during the first half of the 20th century. This tumultuous period sees the Republican Period, the Japanese invasion, and the early days of the People’s Republic of China. The series is great in providing insights into how people used to live, from dress to daily life matter. The scenery and sets are beautiful.

Some Book Recommendations Based on This List:

* Chinese Television in the Twenty-First Century: Entertaining the Nation (Routledge Contemporary China Series Book 121)

* Staging Corruption: Chinese Television and Politics (Contemporary Chinese Studies)

* Television in Post-Reform China: Serial Dramas, Confucian Leadership and the Global Television Market (Routledge Media, Culture and Social Change in Asia)

* TV Drama in China (TransAsia: Screen Cultures)

* Media in China: Consumption, Content and Crisis

Want to know more? Check out our various Top 10s of popular Chinese TV Dramas from 2013 to present here.

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

*1(We kindly ask not to reproduce this list without permission – please link back if referring to it).

References

Bai, Ruoyun. 2007. “TV Dramas in China – Implications of the Globalization.” In Manfred Kops and Stefan Ollig (eds), Internationalization of the Chinese TV sector, 75-99. Berlin: LIT Verlag.

Bai, Ruoyun. 2014. Staging Corruption: Chinese Television and Politics. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Barmé, Geremie. 2012. “Red Allure and the Crimson Blindfold.” China Perspectives, 2012/2, 29-40.

Di, Miao. 2008. “A Brief History of Chinese Situation Comedies.” In Ruoyun Bai, Ying Zhu, Michael Keane (eds), TV Drama in China, 117-129. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Hong, Junhao. 2007. “The Historical Development of Program Exchange in the TV Sector.” In Manfred Kops and Stefan Ollig (eds), Internationalization of the Chinese TV sector, 25-40. Berlin: LIT Verlag.

–. 2007b. “From Three Kingdoms the Novel to Three Kingdoms the Television Series: Gains, Losses, and Implications.” In Kimberly Besio and Constantine Tung (eds), Three Kingdoms and Chinese Culture, 125-143. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Zhu, Ying. 2008. “Yongzheng Dynasty and Totalitarian Nostalgia.” In Bai R, Keane M, Zhu Y. (eds), TV Drama in China, 21-33. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press; 2008

Wang, Min and Arvind Singhal. 1992. “Kewang, A Chinese Television Soap Opera With A Message.” Gazette 49: 177-192.

Directly support Manya Koetse. By supporting this author you make future articles possible and help the maintenance and independence of this site. Donate directly through Paypal here. Also check out the What’s on Weibo donations page for donations through creditcard & WeChat and for more information.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2018 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Arts & Entertainment

How K-pop Fans and the 13-Year-Old Daughter of Baidu VP Sparked a Debate on Online Privacy

What began as K-pop fan outrage targeting a snarky commenter quickly escalated into a Baidu-linked scandal and a broader conversation about data privacy on Chinese social media.

Published

2 weeks agoon

March 26, 2025By

Ruixin Zhang

For an ordinary person with just a few followers, a Weibo account can sometimes be like a refuge from real life—almost like a private space on a public platform—where, along with millions of others, they can express dissatisfaction about daily annoyances or vent frustration about personal life situations.

But over recent years, even the most ordinary social media users could become victims of “opening the box” (开盒 kāihé)—the Chinese internet term for doxxing, meaning the deliberate leaking of personal information to expose or harass someone online.

A K-pop Fan-Led Online Witch Hunt

On March 12, a Chinese social media account focusing on K-pop content, Yuanqi Taopu Xuanshou (@元气桃浦选手), posted about Jang Wonyoung, a popular member of the Korean girl group IVE. As the South Korean singer and model attended Paris Fashion Week and then flew back the same day, the account suggested she was on a “crazy schedule.”

In the comment section, one female Weibo user nicknamed “Charihe” replied:

💬 “It’s a 12-hour flight and it’s not like she’s flying the plane herself. Isn’t sleeping in business class considered resting? Who says she can’t rest? What are you actually talking about by calling this a ‘crazy schedule’..”

Although the comment may have come across as a bit snarky, it was generally lighthearted and harmless. Yet unexpectedly, it brought disaster upon her.

That very evening, the woman nicknamed Charihe was bombarded with direct messages filled with insults from fans of Jang Wonyoung and IVE.

Ironically, Charihe’s profile showed she was anything but a hater of the pop star—her Weibo page included multiple posts praising Wonyoung’s beauty and charm. But that context was ignored by overzealous fans, who combed through her social media accounts looking for other posts to criticize, framing her as a terrible person.

After discovering through Charihe’s account that she was pregnant, Jang Wonyoung’s fans escalated their attacks by targeting her unborn child with insults.

The harassment did not stop there. Around midnight, fans doxxed Charihe, exposing her personal information, workplace, and the contact details of her family and friends. Her friends were flooded with messages, and some were even targeted at their workplaces.

Then, they tracked down Charihe’s husband’s WeChat account, sent him screenshots of her posts, and encouraged him to “physically punish” her.

The extremity of the online harassment finally drew backlash from netizens, who expressed concern for this ordinary pregnant woman’s situation:

💬 “Her entire life was exposed to people she never wanted to know about.”

💬 “Suffering this kind of attack during pregnancy is truly an undeserved disaster.”

Despite condemnation of the hate, some extreme self-proclaimed “fans” remained relentless in the online witch hunt against Charihe.

Baidu Takes a Hit After VP’s 13-Year-Old Daughter Is Exposed

One female fan, nicknamed “YourEyes” (@你的眼眸是世界上最小的湖泊), soon started doxxing commenters who had defended her. The speed and efficiency of these attacks left many stunned at just how easy it apparently is to trace social media users and doxx them.

Digging into old Weibo posts from the “YourEyes” account, people found she had repeatedly doxxed people on social media since last year, using various alt accounts.

She had previously also shared information claiming to study in Canada and boasted about her father’s monthly salary of 220,000 RMB (approx. $30.3K), along with a photo of a confirmation document.

Piecing together the clues, online sleuths finally identified her as the daughter of Xie Guangjun (谢广军), Vice President of Baidu.

From an online hate campaign against an innocent, snarky commenter, the case then became a headline in Chinese state media, and even made international headlines, after it was confirmed that the user “YourEyes”—who had been so quick to dig up others’ personal details—was in fact the 13-year-old daughter of Xie Guangjun, vice president at one of China’s biggest tech giants.

On March 17, Xie Guangjun posted the following apology to his WeChat Moments:

💬 “Recently, my 13-year-old daughter got into an online dispute. Losing control of her emotions, she published other people’s private information from overseas social platforms onto her own account. This led to her own personal information also getting exposed, triggering widespread negative discussion.

As her father, I failed to detect the problem in time and failed to guide her in how to properly handle the situation. I did not teach her the importance of respecting and protecting the privacy of others and of herself, for which I feel deep regret.

In response to this incident, I have communicated with my daughter and sternly criticized her actions. I hereby sincerely apologize to all friends affected.

As a minor, my daughter’s emotional and cognitive maturity is still developing. In a moment of impulsiveness, she made a wrong decision that hurt others and, at the same time, found herself caught in a storm of controversy that has subjected her to pressure and distress far beyond her age.

Here, I respectfully ask everyone to stop spreading related content and to give her the opportunity to correct her mistakes and grow.

Once again, I extend my apologies, and I sincerely thank everyone for your understanding and kindness.”

The public response to Xie’s apology has been largely negative. Many criticized the fact that it was posted privately on WeChat Moments rather than shared on a public platform like Weibo. Some dismissed the statement as an attempt to pacify Baidu shareholders and colleagues rather than take real accountability.

Netizens also pointed out that the apology avoided addressing the core issue of doxxing. Concerns were raised about whether Xie’s position at Baidu—and potential access to sensitive information—may have helped his daughter acquire the data she used to doxx others.

Adding fuel to the speculation were past conversations allegedly involving one of @YourEyes’ alt accounts. In one exchange, when asked “Who are you doxxing next?” she replied, “My parents provided the info,” with a friend adding, “The Baidu database can doxx your entire family.”

Following an internal investigation, Baidu’s head of security, Chen Yang (陈洋), stated on the company’s internal forum that Xie Guangjun’s daughter did not obtain data from Baidu but from “overseas sources.”

However, this clarification did little to reassure the public—and Baidu’s reputation has taken a hit. The company has faced prior scandals, most notably a the 2016 controversy over profiting from misleading medical advertisements.

Online Vulnerability

Beyond Baidu’s involvement, the incident reignited wider concerns about online privacy in China. “Even if it didn’t come from Baidu,” one user wrote, “the fact that a 13-year-old can access such personal information about strangers is terrifying.”

Using the hashtag “Reporter buys own confidential data” (#记者买到了自己的秘密#), Chinese media outlet Southern Metropolis Daily (@南方都市报) recently reported that China’s gray market for personal data has grown significantly. For just 300 RMB ($41), their journalist was able to purchase their own household registration data.

Further investigation uncovered underground networks that claim to cooperate with police, offering a “70-30 profit split” on data transactions.

These illegal data practices are not just connected to doxxing but also to widespread online fraud.

In response, some netizens have begun sharing guides on how to protect oneself from doxxing. For example, they recommend people disable phone number search on apps like WeChat and Alipay, hide their real name in settings, and avoid adding strangers, especially if they are active in fan communities.

Amid the chaos, K-pop fan wars continue to rage online. But some voices—such as influencer Jingzai (@一个特别虚荣的人)—have pointed out that the real issue isn’t fandom, but the deeper problem of data security.

💬 “You should question Baidu, question the telecom giants, question the government, and only then, fight over which fan group started this.”

As for ‘Charihe,’ whose comment sparked it all—her account is now gone. Her username has become a hashtag. For some, it’s still a target for online abuse. For others, it is a reminder of just how vulnerable every user is in a world where digital privacy is far from guaranteed.

By Ruixin Zhang

Independently covering digital China for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Memes & Viral

How Ne Zha 2’s Shen Gongbao Became Known as the Ultimate “Small-Town Swot”

Published

1 month agoon

March 1, 2025

PART OF THIS TEXT COMES FROM THE WEIBO WATCH PREMIUM NEWSLETTER

Over the past few weeks, the Chinese blockbuster Ne Zha 2 has been trending on Weibo every single day. The movie, loosely based on Chinese mythology and the Chinese canonical novel Investiture of the Gods (封神演义), has triggered all kinds of memes and discussions on Chinese social media (read more here and here).

One of the most beloved characters is the leopard demon Shen Gongbao (申公豹). While Shen Gongbao was a more typical villain in the first film, the narrative of Ne Zha 2 adds more nuance and complexity to his character. By exploring his struggles, the film makes him more relatable and sympathetic.

In the movie, Shen is portrayed as a sometimes sinister and tragic villain with humorous and likeable traits. He has a stutter, and a deep desire to earn recognition. Unlike many celestial figures in the film, Shen Gongbao was not born into privilege and never became immortal. As a demon who ascended to the divine court, he remains at the lower rungs of the hierarchy in Chinese mythology. He is a hardworking overachiever who perhaps turned into a villain due to being treated unfairly.

Many viewers resonate with him because, despite his diligence, he will never be like the gods and immortals around him. Many Chinese netizens suggest that Shen Gongbao represents the experience of many “small-town swots” (xiǎozhèn zuòtíjiā 小镇做题家) in China.

“Small-town swot” is a buzzword that has appeared on Chinese social media over the past few years. According to Baike, it first popped up on a Douban forum dedicated to discussing the struggles of students from China’s top universities. Although the term has been part of social media language since 2020, it has recently come back into the spotlight due to Shen Gongbao.

“Small-town swot” refers to students from rural areas and small towns in China who put in immense effort to secure a place at a top university and move to bigger cities. While they may excel academically, even ranking as top scorers, they often find they lack the same social advantages, connections, and networking opportunities as their urban peers.

The idea that they remain at a disadvantage despite working so hard leads to frustration and anxiety—it seems they will never truly escape their background. In a way, it reflects a deeper aspect of China’s rural-urban divide.

Some people on Weibo, like Chinese documentary director and blogger Bianren Guowei (@汴人郭威), try to translate Shen Gongbao’s legendary narrative to a modern Chinese immigrant situation, and imagine that in today’s China, he’d be the guy who trusts in his hard work and intelligence to get into a prestigious school, pass the TOEFL, obtain a green card, and then work in Silicon Valley or on Wall Street. Meanwhile, as a filial son and good brother, he’d save up his “celestial pills” (US dollars) to send home to his family.

Another popular blogger (@痴史) wrote:

“I just finished watching Ne Zha and my wife asked me, why do so many people sympathize with Shen Gongbao? I said, I’ll give you an example to make you understand. Shen Gongbao spent years painstakingly accumulating just six immortal pills (xiāndān 仙丹), while the celestial beings could have 9,000 in their hand just like that.

It’s like saving up money from scatch for years just to buy a gold bracelet, only to realize that the trash bins of the rich people are made of gold, and even the wires in their homes are made of gold. It’s like working tirelessly for years to save up 60,000 yuan ($8230), while someone else can effortlessly pull out 90 million ($12.3 million).In the Heavenly Palace, a single meal costs more than an ordinary person’s lifetime earnings.

Shen Gongbao seems to be his father’s pride, he’s a role model to his little brother, and he’s the hope of his entire village. Yet, despite all his diligence and effort, in the celestial realm, he’s nothing more than a marginal figure. Shen Gongbao is not a villain, he is just the epitome of all of us ordinary people. It is because he represents the state of most of us normal people, that he receives so much empathy.”

In the end, in the eyes of many, Shen Gongbao is the ultimate small-town swot. As a result, he has temporarily become China’s most beloved villain.

By Manya Koetse, with contributions by Wendy Huang

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Subscribe

No Quiet Qingming: From High-Tech Tomb-Sweeping to IShowSpeed & the Seven China Streams

From Trade Crisis to Patriotic Push: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Tariffs

China Trending Week 14: Gucci Fake Lipstick, Xiaomi SU7 Crash, Yoon’s Impeachment

Strange Encounter During IShowSpeed’s Chengdu Livestream

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Beyond the Box Office: What’s Behind Ne Zha 2’s Success?

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

15 Years of Weibo: The Evolution of China’s Social Media Giant

Tuning Into the Year of the Snake

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

TikTok Refugees, Xiaohongshu, and the Letters from Li Hua

The ‘China-chic Girl’ Image and the Realities of China’s Competitive Food Delivery Market

“Black Myth: Wukong”: From Gaming Screens to the CMG Spring Festival Gala?

US-Russia Rapprochement and “Saint Zelensky”: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Shake-Up

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight11 months ago

China Insight11 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

-

China Arts & Entertainment11 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment11 months agoSinging Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Ben

November 16, 2018 at 10:33 am

In the picture for “#18 Heaven’s Above (苍天在上)”, the character seems to be holding a smartphone – possibly an iPhone given what looks to be an apple on the back side. That would be anachronistic for a 1995 series I think?

Admin

November 16, 2018 at 10:41 am

Well spotted, Ben! You’re right! That was an image from a modern remake mini-series of Heaven’s Above (苍天在上), not the 1995 version. We’ve now replaced with an image from the original show. Thanks for the heads up 🙂

autraka

November 22, 2018 at 6:59 am

Wish you included 武林外传、还珠格格 and more TV dramas based on 金庸‘s novels.

Brown

January 2, 2019 at 10:58 am

Chinese TVs set in Qing Dynasty are an amazing series for me. I love the Story of Yanxi Palace especially. I have found the top 10 related Qing Dynasty TVs from here

https://chinausual.com/top-10-chinese-tv-series-set-in-qing-dynasty/

Jason

February 23, 2019 at 9:57 am

Actually “White Deer Plain” 白鹿原 is in Shaanxi(陕西). Not Shanxi(山西)。