China Media

Top 6 of China’s Popular News Apps

In an online environment with hundreds of news apps, these are some must-know apps Chinese netizens use to stay updated on the news.

Published

6 years agoon

By

Gabi Verberg

In China’s dynamic online media environment, where hundreds of news apps are competing over clicks, these are five different news apps that are currently popular among Chinese netizens.

China is the world’s largest smartphone market, and the mobile app business is booming. Chinese netizens, of which some 98% access the internet via mobile phone, have thousands of app to choose from across dozens of app stores.

To provide some insights into this huge market, What’s on Weibo has listed some of the most popular and noteworthy apps in China today in various categories, namely news, education, health, games, and short video & live streaming. Check our top 5 of most popular short video apps here. This article will focus on some of China’s most popular news apps. Stay tuned for the other categories, that will follow shortly and will be listed below this article.

We made our selection based on the data from the Android app stores Tencent, Baidu, Huawei, and Zhushou360. We tried our best to give you a representative overview of a variety of apps that are currently most used in China, but want to remind you that these lists are by no official “top 5” charts.

When it comes to news apps, we see there’s a clear preference for the more commercial media outlets rather than traditional Chinese state media newspaper titles, and that besides gaming, live streaming, shopping, and music, news gathering is still very much a popular online activity among Chinese netizens.

#1 Jinri Toutiao 今日头条

Jinri Toutiao, which translates as ‘Today’s Headlines’, currently ranks as the most popular app in the Chinese Apple store, together with its ‘speed version’ (今日头条极速版) version, which offers a different interface.

The Jinri Toutiao app is a core product of China’s tech giant Bytedance Inc., which has also developed popular apps such as TikTok, Douyin (抖音), Xigua (西瓜) and Huoshan (火山).

The main difference between the normal and speed version app is that the Jinri Toutiao has some extended features; its layout can be adjusted according to user’s preferences and its installment takes up more space on the device.

Toutiao’s success is mainly due to its artificial intelligence functions that sources news and other articles for its users. Through the app’s machine-learning algorithm, Jinri Toutiao can understand its user’s preferences and personalizes the selected content its shows on the main page. In doing so, Toutiao is a so-called news aggregator that has some 4000 news providing partners and is comparable to American apps such as Flipboard.

In 2018, Jinri Toutiao had 700 million registered users, with 120 million daily readers, spending approximately 76 minutes on the app, viewing a total of 4.2 billion(!) articles.

#2 Ifeng News 凤凰新闻

Ifeng News or Phoenix News is part of Phoenix TV, a broadcasting company established in 1996. The media company, that is headquartered in Hong Kong, is active in traditional media as well as in new media.

According to Phoenix TV, users of the Ifeng News app approximately spend more than 37 minutes on the app daily.

Like Toutiao, the Ifeng News app also offers personalized content for users based on AI algorithms. Different from Toutiao, Ifeng is not just a news aggregator but also produces its own content.

Ifeng News is the app to consult when you want to get somewhat more in-depth insights into the main headlines from around globe. In addition, Ifeng also offers 24/7 live news broadcasts from mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

#3 Caijing Toutiao 财经头条

Caijing Toutiao is an app developed by Caijing Magazine, an independent financial magazine based in Beijing that, in addition to economic issues, also focuses on social and public affairs and civil rights. It has long been known for its progressive and critical content, which is why we list it here, although some other commercial news apps, such as Tencent News, Sohu News, Netease, and The Paper, might be more popular in terms of the total number of downloads.

Caijing Magazine was established in 1998 by Hu Shuli (胡舒立) as part of the Media Group Limited. Especially in the first ten years of the magazine’s existence, it enjoyed relative freedom regarding press restrictions. But the ‘golden era’ of Caijing came to an end in 2009, when Hu Shili resigned after facing more control over news by the authorities.

Nevertheless, Caijing is still known as an authoritative news platform for business and financial issues in China.

The Caijing app, in addition to its live stream and headlines, offers rich financial content organized in various categories. The app is not only among the most popular news apps, but it was also ranked the most downloaded financial app in the first half of 2018.

#4 People’s Daily 人民日报

People’s Daily, one of the leading news outlets of China, is the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. The news office was established in 1948 and is headquartered in Beijing.

Despite being seventy years old, People’s Daily has adopted various strategies over the past years to reach Chinese younger audiences in the digital era. The news app, launched in 2014, is part of its digital strategy, and now ranks amongst the most popular news apps of China across different app app stores.

A large number of People’s Daily‘s news articles focus on political matters. Users of the app can choose whether they want to see the standardized content showed to all users, or opt-in to recommended articles based on monitored personal preferences.

#5 Tencent News 腾讯新闻

Tencent News, which is part of the Shenzhen-based Tencent Group, is one of the leading news-apps of China. In addition to the app, the company also has its online portal QQ.com, where they release the same content as the app, complemented with other services.

In 2017, Tencent brought the two apps together when it added a news feed and search function to its super app WeChat. This means that, regardless if you have the Tencent News app installed on your device, you will be directed to Tencent News when you enter certain search words in WeChat. With WeChat’s 1.08 billion monthly active users globally, this sets off a tremendous user flow from WeChat to Tencent News.

The majority of the news articles on the app come from third-party platforms. In addition to the news, the app features other Tencent products such as Tencent Video and their live streaming service.

In the final quarter of 2018, Tencent News users grew from 94 million to 97.6 million daily active users, making it the second most popular news app of China.

#6 Zhihu 知乎

Zhihu is no typical news app: it actually is China’s biggest Q&A platform, comparable to Quora.

In 2018, Zhihu had 160 million registered users, of which 26 million visited the app daily. Despite the fact that Zhihu is not a traditional news content app, it plays an important role in China’s online news media landscape, as it provides an open space where users get (news) information and can get answers to their questions relating to the news and other things.

What sets it apart from other social media platforms is that users do not need to be ‘connected’ or ‘follow’ each other in order to see each other’s questions and comments. Zhihu‘s algorithm pushes up the most popular content, driving engagement.

How does Zhihu exactly work? All Zhihu users can create topics or questions, and reply to those of others. By voting on the best response of other users, the app automatically features the most appreciated comments on the top of the page.

To guarantee the reliability of the information provided by users, Zhihu has rolled out a ‘point system’ that credits users for their content, profile, and behavior on the platform. By giving every user a personal score, Zhihu allegedly hopes to promote more “trustworthy” content.

Apart from the Q&A feature, Zhihu also offers electronic books and paid live streaming. Zhihu also launched the so-called ‘Zhihu University’ that offers paid online courses in business, science, and humanities.

Also see:

By Gabi Verberg, edited by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2019 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Gabi Verberg is a Business graduate from the University of Amsterdam who has worked and studied in Shanghai and Beijing. She now lives in Amsterdam and works as a part-time translator, with a particular interest in Chinese modern culture and politics.

You may like

China Insight

China Reacts: 3 Trending Hashtags Shaping the Tariff War Narrative

From historic speeches to trending slogans, this is China’s official media response to the US tariff escalation.

Published

1 week agoon

April 13, 2025

What do Mao’s 1953 Korean War speech and Yang Jiechi’s 2021 Alaska Summit remarks have to do with the escalating US–China trade war? In Chinese official media responses, history and emotionally charged rhetoric are used to clearly signal China’s stance and boost national confidence. Here, we explore three dominant narratives.

As you probably know by now, April 9 marked “D-Day” for Trump’s rollout of steep tariffs. On Chinese social media, the escalating trade war between China and the US dominated conversation, especially on that “D-Day Wednesday,” when nearly all of Weibo’s top 10 most-viewed hashtags were related to Trump’s tariffs and China’s retaliation.

Since developments are unfolding rapidly, here’s a quick recap:

- 🇺🇸💥 On Wednesday, April 2, President Trump announced steep new tariffs, including a universal 10% “minimum base tariff” on all imported goods, and an additional 34% reciprocal tariff specifically targeting China as part of the so-called “Liberation Day,” set to begin on April 9. Combined with pre-existing tariffs, this would bring the total tariff rate on Chinese goods entering the United States to over 54%.

- 🇨🇳⚔️On Friday, April 4, China’s State Council Customs Tariff Commission Office issued an announcement stating that, starting April 10, an additional 34% tariff would be levied on all imported goods originating from the United States, on top of existing tariff rates.

- 🇺🇸⚔️On Tuesday, April 8, Trump vowed to increase tariffs on Chinese exports by an additional 50% if Beijing would not withdraw its 34% counter-tariffs.

- 🇨🇳💥On Wednesday, April 9, China’s finance ministry announced it would further raise tariffs on US goods to 84% starting the following day, in retaliation for the newly imposed 104% tariff on Chinese goods.

- 🇺🇸💣On Wednesday, April 9, Trump then did a U-turn and halted the new steep tariffs for dozens of countries for 90 days, except for China, followed by yet another threat of an additional 21%, bringing those import taxes to 125%.

- 🇺🇸🚨On Thursday, April 10, it was clarified by the White House that tariffs on China would actually total 145%, combining the previously announced 125% with a 20% import tax levied for fentanyl smuggling.

- 🇨🇳💣On Friday, April 11, Chinese official channels reported that China would adjust its tariff measures on important goods from the US starting April 12, raising the rate from 84% to 125%. A related hashtag became no 1 trending topic on Weibo, where it received over 500 million views by Friday night (#对美所有进口商品加征125%关税#).

- 🇺🇸⬅️ On Friday, April 11, Trump’s administration announced that it will exempt smartphones, computers and some other electronic devices from the new tariffs, including the 125% levies imposed on Chinese imports (#特朗普政府再度退缩#; #美国免除智能手机电脑对等关税#).

There are hundreds of hashtags and trending topics circulating across Chinese platforms — from Weibo to Toutiao, from Kuaishou to Douyin — related to the latest developments in the US–China trade war. The topic is super popular, but censored comment sections and removed images also reveal just how sensitive it can be at times.

The biggest hashtags and slogans are those initiated and amplified by official channels. From press conferences to hashtags and visual propaganda, you can see a clear strategic media narrative that draws on history, national pride, and patriotism to frame recent developments, mobilize public sentiment domestically, and show China’s resilience to the rest of the world.

Here, I’ll highlight three hashtags that have recently become top trending, each representing a different kind of official narrative or rhetoric in response to the ongoing developments.

1. China Won’t Back Down

(China will see it through to the end #美方一意孤行中方必将奉陪到底#)

The message that China will not be intimidated by the US is one that echoes across Chinese social media these days, reinforced by official channels.

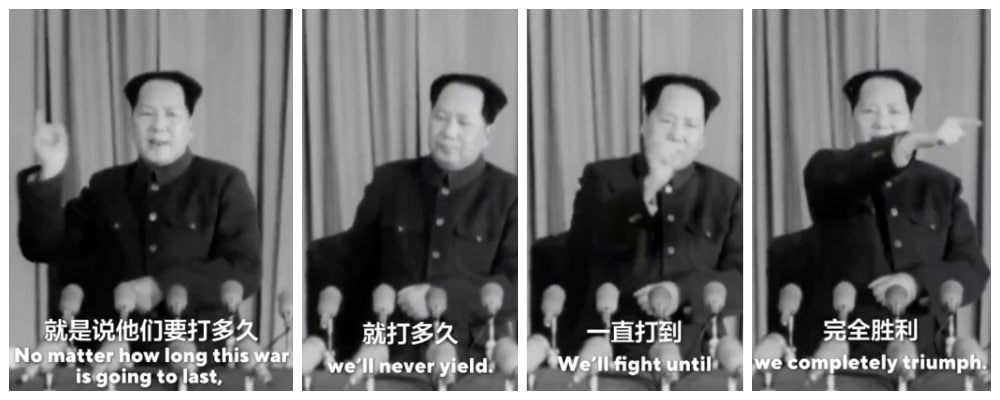

On April 9, the Weibo account of Chinese media outlet Guancha (@观察者网) and the state-run New Era China Foreign Affairs Think Tank (@新时代中国外交思想库) posted a video showing part of a speech given by Mao Zedong on February 7, 1953, during the final stages of the Korean War at the 4th Session of the 1st National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC).

In the short fragment, Mao Zedong says:

🇨🇳📢 “As to how long this war will last, we are not the ones who can decide. It used to depend on President Truman, and it will depend on President Eisenhower, or whoever becomes the next US President. It’s up to them. No matter how long this war is going to last, we’ll never yield. We’ll fight until we completely triumph.”

The 1953 speech by Mao was also posted on the US social media platform X by Mao Ning (@毛宁), spokesperson for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The video was then also spread by blogging accounts and regular netizens. History blogger Zijin Gongzi (@紫禁公子), who has over 435k fans on Weibo, reposted the video, writing:

💬 “Our forefathers never bowed their heads to strong enemies. How could we easily accept defeat? (..) We must not lose this spirit, we must let everyone know that we have a strong backbone and will never bow down.”

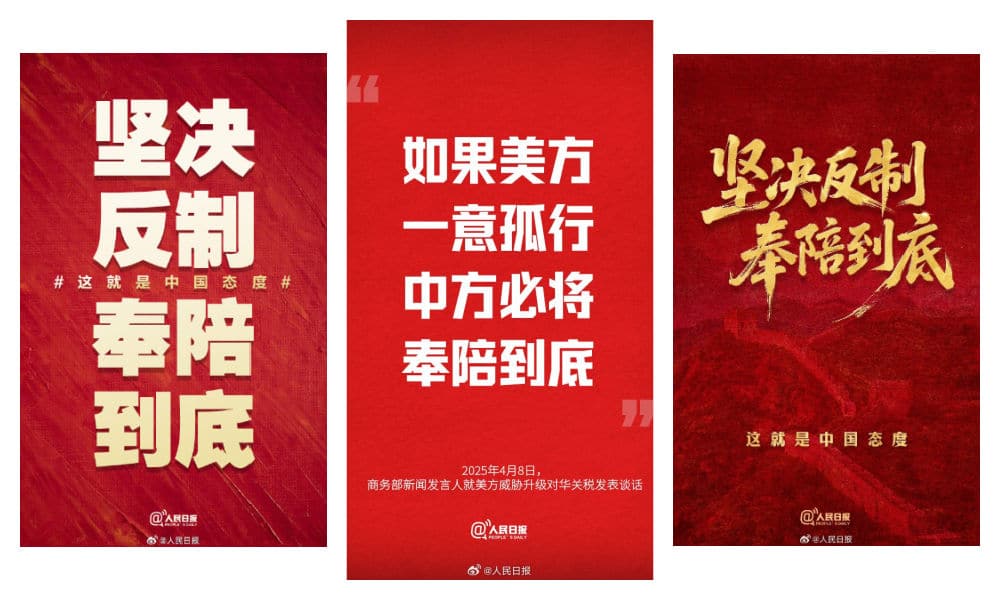

Together with the Mao video, the hashtag used by the Think Tank and many other Chinese media accounts, such as People’s Daily (@人民日报), is “If the US obstinately clings to its course, China will fight to the end [lit. accompany them to the end]” (#美方一意孤行中方必将奉陪到底#) and “fight to the end” (#我们奉陪到底#).

These phrases in part come from a press conference given by Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Lin Jian (林剑) on April 8. Here, he said:

🇨🇳📢 “I want to emphasize once again that there are no winners in trade wars and tariff wars, and protectionism is no way forward. The Chinese people do not provoke trouble, but they are also not afraid. Pressure, threats, and blackmail are not the proper ways to deal with China. China will inevitably take necessary measures and resolutely safeguard its legitimate rights and interests. If the American side disregards the interests of both countries and the international community and insists on waging a tariff war and trade war, China will fight to the end [lit. inevitably accompany them to the end 中方必将奉陪到底].”

The next day, these words had been turned into digital propaganda posters, with some slight variations in the phrases used. One People’s Daily graphic underlined: “We resolutely take countermeasures, and follow through until the end (坚决反制 奉陪到底),” accompanied by the line: “This is China’s attitude,” which was also turned into a hashtag (#这就是中国态度#).

2. This Is No Way to Deal with China

(Chinese people aren’t buying it #中国人从来不吃这一套#)

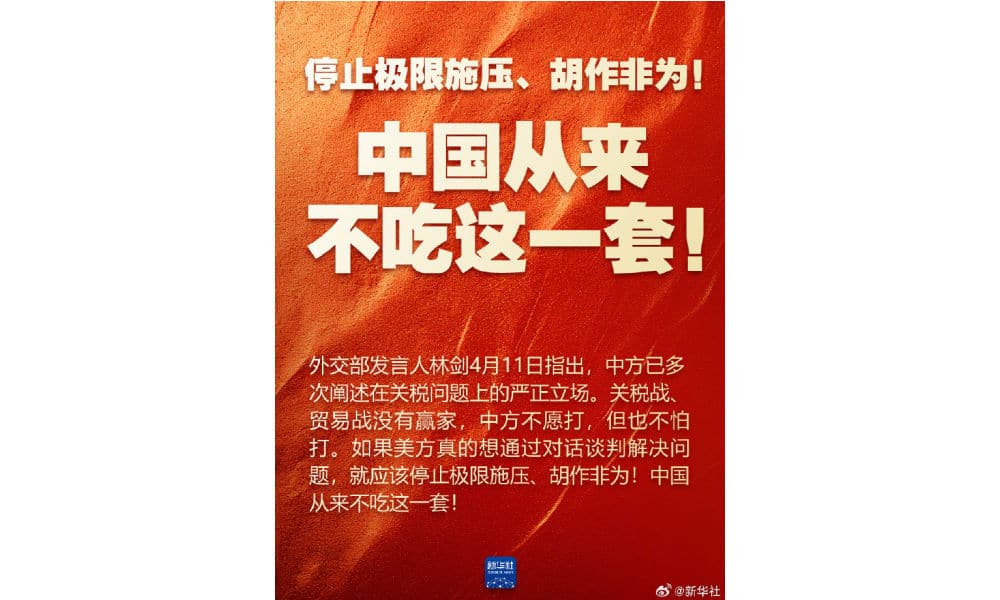

Another related yet somewhat different sentiment that dominates Chinese social media—led by official channels—is that China is not only rejecting the trade games played by the US, but is also distancing itself from the American playbook. The message is: this is no way to deal with China. This narrative, and the hashtag surrounding it, emerged slightly later than the first. While the earlier phrase about China not backing down trended as China matched the US in its tariff measures, this one took off with China’s final blow—raising the rate on US imports from 84% to 125% in response to the latest US tariff hikes.

The April 11 statement on the Ministry of Finance website (财政部网站), also posted on Weibo by Xinhua News (@新华社), announced that China would adjust its additional tariff measures on imports originating from the United States effective April 12. It also stated that China strongly condemns the US imposition of excessively high tariffs and will no longer engage in further tariff escalations:

🇨🇳📢 “Given that, at the current tariff level, US goods entering China effectively have no market viability, if the US continues to raise tariffs on Chinese exports to the US, China will no longer respond.”

The main hashtag used by Xinhua and many other media channels is “中国从来不吃这一套” (Zhōngguó cónglái bù chī zhè yī tào), which can be translated as: “The Chinese people have never accepted this,” or more colloquially, “We’re not buying it.”

The phrase initially became popular in 2021, after it was used by China’s top diplomat Yang Jiechi (杨洁篪) during the first major strategic talks of the Biden administration, held in Anchorage on March 19. Due to the occasionally heated exchanges between the two delegations, some called the Alaska talks a “diplomatic clash.”

Yang Jiechi during the Alaska Summit

At the time, Yang delivered a lengthy statement to US Secretary of State Antony Blinken and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, stressing that Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Xinjiang are “inseparable parts of China,” and that China strongly opposes US interference in its internal affairs. Suggesting the US should focus more on its own human rights issues and racial problems instead of lecturing China, he added the now-famous line: “The US is not qualified to speak to China from a position of strength. The Chinese people don’t buy that” (美国没有资格居高临下同中国说话,中国人不吃这一套).

The phrase quickly went viral—boosted by state media, celebrated by netizens, and turned into a marketing slogan. It now appears on t-shirts, teacups, phone cases, and other patriotic merchandise.

The translation of the phrase still triggers discussions. While merchandise typically translates it as “Stop interfering in China’s internal affairs,” that’s not an accurate translation. During the Alaska Summit, interpreter Zhang Jing (张京) (who gained viral fame at the time) translated it in real-time as “This is not the way to deal with the Chinese people.” However, some commentators and professional translators argued this was a missed opportunity to take a tougher stance, as the Chinese phrase is much sharper and could be loosely translated as: “We Chinese people don’t swallow this crap.”

In Alaska, Yang emphasized that dealing with China requires mutual respect, and that history will prove that trying to strangle China’s rise would ultimately hurt the US itself (“与中国打交道,就要在相互尊重的基础上进行。历史会证明,对中国采取卡脖子的办法,最后受损的是自己。”)

Similar sentiments now dominate online media discourse in China. The slogan has evolved from “The Chinese people don’t buy this” (中国人不吃这一套) to the more authoritative “China has never bought this” (#中国从来不吃这一套#)

Adding fuel to this message are hashtags like “America’s repeated imposition of excessively high tariffs on China has become a joke” (#美方对华轮番加征畸高关税已沦为笑话#).

Ridiculing America (especially Trump) has become a popular pastime on Chinese social media this past week, with a flood of Chinese and international memes circulating widely.

Especially popular are memes mocking the idea of America as a future “Made-in-America” manufacturing hub, the irony of iconic American products (like MAGA hats) being made in China, and how everyday essentials such as eggs have reached historic price highs in the US (a crisis partly caused by bird flu but now worsened by the tariffs).

On April 13, the hashtag “The 145% tariff makes one panda plush toy cost 80 dollars” (#145%关税让1只熊猫玩偶卖80美元#) also went trending, sparking jokes about how even the most trivial things could suddenly become luxuries in the US.

3. China is the Most Stabile Superpower

(Countering America’s madness with China’s stability #以中国稳应对美国疯#)

A third stance that has been dominant in Chinese official online discourse is that China’s development does not rely on anyone’s favors (#中国发展从不靠谁的恩赐#, derived from a quote by Xi Jinping), and that despite the US’s measures, China’s rise on the world stage cannot be stopped. In fact, the narrative suggests that these actions by the US are only accelerating China’s ascent.

A commentary piece published by state broadcaster CCTV (@央视新闻) on April 11 quoted Professor Li Haidong (李海东) of China Foreign Affairs University, who stated that the US’s increasingly aggressive behavior reinforces the notion that it is using tariffs as a tool of extreme pressure; as a weapon to serve its own interests. According to Li, this reflects America’s hegemonic mindset, aiming to assert superiority by intentionally creating crises.

But rather than strengthening the US, the commentary argues, these recent measures are backfiring and are damaging the US’s domestic economy and undermining its global credibility.

In contrast to the US’s presumed recklessness and “hysterical approach,” China is depicted as a “responsible world leader,” bringing certainty to an uncertain world by “responding with its own stability” and proving to be, supposedly, a more reliable engine of global growth. The commentary states:

🇨🇳📢 “As the tariff storm strikes, China is using its own ‘stability’ to resist the trials and tribulations, by upholding rules, defending justice, and steering the big ship of globalization through treacherous countercurrents, toward the right path of openness and cooperation.”

To promote the piece on social media, CCTV used the hashtag “Responding to America’s madness with China’s stability” (#以中国稳应对美国疯#).

This sentiment was echoed by nationalist bloggers, such as Tangzhe Tongxue (@唐哲同学), who posted on April 13:

💬 “In this world, besides China, the rest are all just a poorly equipped small-town theater troupe (草台班子).”

The phrase “草台班子” (cǎotái bānzi) literally refers to a makeshift opera troupe performing on a shabby rural stage, and is used to describe an incompetent group of amateurs.

The blogger’s comment indirectly responds to comments made by US Vice President JD Vance, who defended Trump’s tariffs in a Fox News interview by saying: “To make it a little more crystal clear, we borrow money from Chinese peasants to buy the things those Chinese peasants manufacture.”

That remark sparked controversy online, with many netizens calling it ignorant. Some pointed out that Chinese people were already wearing fine silks when Westerners were still wrapped in animal skins fishing in the sea, and flipping the narrative to portray Americans as the real “country bumpkins.”

Meme shared online.

This sentiment was reinforced by another hashtag trending on Weibo on April 13: “You think we’re scared, but we actually don’t care” (#你以为我们scared其实我们不care#).

That line comes from a Channel 4 interview with Gao Zhikai (Victor Gao/高志凯), Vice President of the Center for China & Globalization (CCG), who stated:

🇨🇳📢 “China is fully prepared to fight to the very end. Because the world is big enough that the United States is not the totality of the market in the world. So if the United States wants to go in that direction of completely shutting itself out of the Chinese market, be my guest. [Interviewer: Yes and China will lose the US market..] We don’t care. We don’t care. China has been here for 5000 years, and for most of the time there was no United States and we survived. If the United States wants to bully China, we will deal with the situation without the United States. And we except to survive for another 5000 years.”

While this reflects the official position and is widely echoed across social media, others stress the importance of remembering history; particularly China’s “Century of Humiliation” (百年国耻), which was marked by war, aggression, and unequal treaties imposed by foreign powers. Just like other historical anniversaries, some bloggers argue that Trump’s tariff “D-Day,” April 9, should not be forgotten (“今天是每个中国人难以释怀的日子”) and that it marks another reason for China’s renewed rise.

In a video posted by CCTV’s short video platform Xiaoyang Shipin (小央视频) on April 13 (link), the narrator states:

🇨🇳📢 “The so-called global “beacon” now puts “America first.” It slaps allies in the face, treats the world with predatory practices, and makes other countries pay for MAGA, pushing the fragile word economy over the edge, and pitching itself against the whole world. With China here, the sky won’t fall. With around 5% economic growth, China adds the output of a mid-sized European economy every year. China has hundreds of millions of skilled workers. The Chinese people are well known for their strong work ethic. China’s development over the past seven decades is a result of self-reliance and hard work, not favors from others, (..) Global businesses believe the next China is still China and the best is yet to come (..) Markets need to restore faith. Between the pond of closed markets, and the ocean of economic interconnectivity, which one would you choose?”

Overall, packaged across different media — from hashtags to short videos, from press conferences to news reports, and from digital slogan posters to Ministry of Foreign Affairs tweets — China’s strategic political media messaging is clear and quite powerful, despite the fragile and censored environment it operates in: China is not afraid to strike back, China will lead with calm, and eventually, China will emerge as the winner. Whatever happens next remains to be seen, but when it comes to turning crisis into opportunity, China’s official media channels have already done just that.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

THIS ARTICLE IS PART OF WHAT’S ON WEIBO CHAPTER: “THE US-CHINA TARIFF WAR ON CHINESE SOCIAL MEDIA“

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Insight

From Trade Crisis to Patriotic Push: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Tariffs

“This moment is the time to reflect on our unity. If we can choose domestic alternatives, we should.”

Published

2 weeks agoon

April 5, 2025

“China’s countermeasures are here” (#中方反制措施来了#). This hashtag, launched by Party newspaper People’s Daily, went top trending on Chinese social media on Friday, April 4, after President Trump announced steep new tariffs on Wednesday, including a universal 10 percent “minimum base tariff” on all imported goods and especially targeting China with an additional 34% reciprocal tariff as part of so-called “liberation day.”

Countermeasures were announced on Friday. China’s State Council Customs Tariff Commission Office (国务院关税税则委员会办公室) issued an announcement stating that, starting from April 10, an additional 34% tariff will be levied on all imported goods originating from the United States, on top of existing tariff rates.

Other countermeasures include immediate export restrictions on seven key medium to heavy rare earth elements, which are important for manufacturing critical products used in semiconductors, defense, aerospace, and green energy.

“This won’t make America great again”

The official response to the tariffs, both from state media and the government, has been twofold: on the one hand, it criticizes the U.S. for placing American interests above the good of the global community, arguing that the move only hurts the U.S., its people, and the world. On the other hand, the Chinese side stresses that although they do not believe tariff wars are the answer, China is not afraid of a trade war and will not sit idly by, but will respond with equal measures.

Chinese official media have condemned the new tariffs, which led to the largest single-day market drop in years. Describing the reactions of various experts, Xinhua News highlighted a comment by a Croatian professor, stating that the policy will only increase export prices and worsen inflation, ultimately hurting middle- and working-class Americans — and noting that the policy “won’t make America great again” (不会“让美国再次伟大”).

The official announcement by Chinese state media regarding China’s countermeasures received widespread support in its (highly controlled) comment sections, with both media outlets and netizens echoing the message that China will not be bullied by the U.S.

On Xiaohongshu, similar sentiments shnone through in popular posts, such as one person writing:

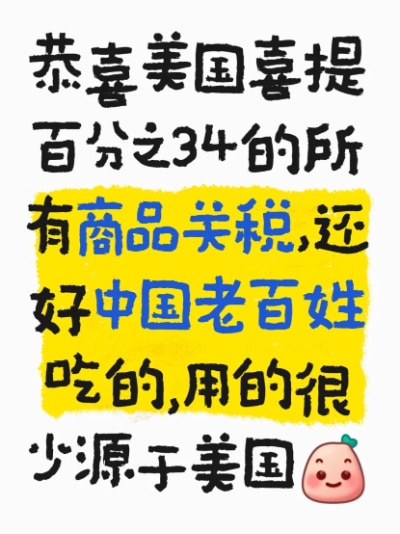

💬 “Congratulations to the U.S. on receiving a 34% tariff on all its goods! Luckily, very few of the things ordinary Chinese people eat or use come from the U.S. anyway.

#RMB purchasing power #China will inevitably be unified #Consumer confidence #Contemporary Chinese economy #Carrying forward the construction of a Beautiful China”

“Monday’s stock market will be a bloodbath,” another commenter wrote.

One Weibo blogger (@兰启昌) saw the recent developments as another sign of an ongoing trend of “de-globalization” (逆全球化).

But beyond global economics and geopolitics, many Chinese netizens — from Weibo to Xiaohongshu — seem more focused on how the new policies will affect everyday consumers.

Netizens have been actively discussing which goods will be hit hardest by the new tariffs. Based on 2023 trade data, here’s a breakdown of the top exports between China and the United States — and the sectors most likely to feel the impact.

🔷🇺🇸🇨🇳Top 10 Chinese Exports to the U.S.

1. Electronics and Machinery

Includes smartphones, laptops, tablets, integrated circuits, and image processing equipment.

2. Furniture, Home Goods & Toys

Such as video game consoles, lamps, and much more.

3. Textiles and Apparel

Garments, footwear, and accessories like sunglasses.

4. Metals and Related Products

Especially steel and steel-based items.

5. Plastic and Rubber Products

Widely used in packaging, manufacturing, and consumer goods.

6. Transportation Equipment

Electric vehicles, passenger cars, motorcycles, scooters, and drones.

7. Low-Value Commodities

Bulk items used in general trade and low-cost manufacturing.

8. Chemicals

Industrial chemicals and related materials.

9. Medical and Optical Instruments

Includes medical devices and precision instruments.

10. Paper Products

Ranging from office supplies to industrial paper goods.

🔹🇨🇳🇺🇸Top 10 U.S. Exports to China

1. High-Tech Machinery and Electronics

Especially integrated circuits, turbine engine components, and semiconductor manufacturing equipment.

2. Energy Products

Crude oil, liquefied propane and butane, natural gas, and coking coal.

3. Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals

Includes cosmetics, cleaning agents, and various medical drugs.

4. Soybeans

A key agricultural export widely used in food and animal feed in China.

5. Transportation Equipment

Such as automobiles and aircraft parts.

6. Medical and Optical Devices

Medical precision equipment, diagnostic tools, and lab instruments.

7. Plastic and Rubber Goods

Used in both consumer and industrial sectors.

8. Metal Products

Primarily iron and steel exports.

9. Wood and Pulp Products

Lumber, wood pulp, charcoal, and paper goods.

10. Meat

Including beef, pork, and poultry.

Those doing trade with the US, or otherwise involved in made-in-China products, like those working clothing and furniture factories, will inevitably be affected by the tariffs.

“Patriotism isn’t just a sentiment – it’s an action”

Much of the popular online conversation has focused on concrete examples of what kinds of things might get more expensive for Chinese consumers in their everyday lives.

Some bloggers noted that people might start to see price hikes in everyday groceries like dairy, meat, corn, and soybeans. With fewer soybeans coming in from the US, cooking oil prices may also rise.

China is the world’s largest consumer of soybeans, but because domestic production is relatively low, soybeans remain a key import.

Then there are popular American brands in the Chinese market that are expected to get pricier too — like beauty and health products, Starbucks coffee, or Häagen-Dazs ice cream.

Some also predicted a 30% to 40% increase in prices for iPhones and other Apple products.

Contrary to the earlier comment by the Xiaohongshu blogger, some netizens explain just how many American products are actually used by Chinese consumers, with many American companies operating in China — from McDonald’s and Coca-Cola, Walmart to Disney or Warner Brothers, Procter & Gamble to Colgate and Estée Lauder.

What’s noteworthy in these discussions, however, is a strong tendency to point to Chinese alternatives and encourage smart buying instead of following hypes (“理性替代,拒绝跟风”): No need to panic about soybeans — there are domestic alternatives, and China’s own soybean program is getting a boost. Who needs Starbucks when there’s Luckin Coffee? Why buy an iPhone when you can get a Huawei? Skip the Tesla, go for a BYD.

In these discussions, the ‘crisis’ is turned into an ‘opportunity’ for Chinese companies to focus even more on the Chinese market, and for Chinese consumers to, more than ever, actively embrace and celebrate local brands and made-in-China products.

One Chinese blogger (@O浅夏拾光O) wrote:

💬 “This moment is the time to reflect on our unity. If we can choose domestic alternatives, we should. For example, we can use rapeseed oil or peanut oil instead of imported soybean oil; we can buy cost-effective Chinese electronics instead of foreign brands. Support domestic products and respond to the nation’s call to expand domestic consumption.

We must have faith in our country. Only by uniting as one, young and old all together, the entire country working together, can we withstand all hazards. As Professor Ai Yuejin (艾跃进) once said, patriotism isn’t just a sentiment – it’s an action. As long as our core is stable and we are united in spirit, no hardship can defeat us.”

Despite the major happenings and the big words, some people just care about the small things: “As long as KFC and McDonald’s don’t raise their prices, it’s all fine by me.”

See the follow-up to this article here.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Chinese New Nickname for Trump Mixes Fairy Tales with Tariff War

China Trending Week 15/16: Gu Ming Viral Collab, Maozi & Meigui Fallout, Datong Post-Engagement Rape Case

China Reacts: 3 Trending Hashtags Shaping the Tariff War Narrative

No Quiet Qingming: From High-Tech Tomb-Sweeping to IShowSpeed & the Seven China Streams

From Trade Crisis to Patriotic Push: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Tariffs

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Beyond the Box Office: What’s Behind Ne Zha 2’s Success?

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

15 Years of Weibo: The Evolution of China’s Social Media Giant

Tuning Into the Year of the Snake

TikTok Refugees, Xiaohongshu, and the Letters from Li Hua

“Black Myth: Wukong”: From Gaming Screens to the CMG Spring Festival Gala?

US-Russia Rapprochement and “Saint Zelensky”: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Shake-Up

The ‘China-chic Girl’ Image and the Realities of China’s Competitive Food Delivery Market

Collective Grief Over “Big S”

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight12 months ago

China Insight12 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Digital11 months ago

China Digital11 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

-

China Arts & Entertainment11 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment11 months agoSinging Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

-

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers12 months ago

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers12 months agoA Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea