China Society

Two Court Sentences Trending on Weibo: The Xuzhou Chained Mother Case and the Dalian BMW Driver Death Penalty

From Xuzhou to Dalian, the conclusion of these criminal cases was eagerly awaited, with varying opinions on the verdicts and sentences.

Published

2 years agoon

Chinese netizens have been closely following two criminal cases that saw major developments recently. A verdict came out in the Xuzhou chained woman case, and the BMW driver who killed five people was executed. Has justice been served?

The case of a mother of eight children who was found to be chained up in a shed next to the family home became one of the biggest social media topics in China in 2022.

The story first attracted nationwide attention in late January 2022 when a video of the mother, filmed by a local TikTok user, went viral and triggered massive outrage. People demanded answers about the woman’s circumstances and why her husband (Dong Zhimin 董志民) was seemingly exploiting their situation on social media.

The mother, who seemed confused, was kept in a dirty shed without a door in the freezing cold – she did not even wear a coat. Videos showed how her husband Dong Zhimin and their eight children were playing and talking in the family home right next to the hut.

Chinese internet users, from local reporters to internet sleuths and feminists, started investigating the case, wanting to find out who this woman was and if she might have been the victim of human trafficking (read ‘Twists and Turns in the Tragic Story of the Xuzhou Chained Mother‘).

Thanks to the ongoing social media attention surrounding the woman, and with the help of local authorities, it was eventually determined that the woman was indeed a victim of human trafficking and she was identified as Xiao Huamei (小花梅) from Yagu, Fugong County, who went missing – without anyone reporting her missing – in 1996.

On April 7th, 2023, the Xuzhou Intermediate People’s Court in Jiangsu Province delivered its verdict in the case. Dong Zhimin, Xiao Huamei’s husband, was found guilty of abuse and illegal detainment and was sentenced to nine years in prison.

Five other people were also sentenced for their involvement in the case. Shi Lizhong (时立忠), Sang Heniu (桑合妞), Tan Aiqing (谭爱庆), Huo Yongqu (霍永渠), and Huo Fude (霍福得) were found guilty of human trafficking.

Together with Shi Lizhong, Sang Heniu is the woman who lured Xiao Huamei away from her hometown under false pretenses in 1998 and sold her to a man in Donghai County for 5000 yuan ($725) before she ended up with Dong Zhimin. Shi and Sang were sentenced to 11 and 10 years in prison respectively.

It is not entirely clear what happened to Xiao Huamei later in 1998, but she was separated from the first man and was reportedly resold by Tan Aiqing to Huo Yongqu and Huo Fude for 3000 yuan ($435), who then took her to Huankou where she was again resold for 5000 yuan ($725) to Dong Zhimin. Tan Aiqing, Huo Yongqu, and Huo Fude received sentences of 11 years, 10 years, and 13 years respectively.

On Weibo, where the verdict went trending (#丰县八孩案一审宣判#), there were those who said justice has been served, but louder voices expressed that they thought the sentences imposed were still not harsh enough.

One concern people have is that Dong Zhimin has not been sentenced for human trafficking, while many people think that “selling” and “buying” should be equally punished: “Actually, the judgment was too light, the law should be amended and people who buy should also be punished for it.”

Then there are those who just want to know how Xiao Huamei – who is suffering from mental illness – is doing together with her eight children and what will happen to them now that Dong is in prison. Those questions are still left unanswered.

Execution of Culprit in Dalian Shocking Hit-and-Run Case

The execution of Liu Dong, a man who was sentenced to death for plowing into a group of pedestrians, was the other major criminal case that went trending recently.

On May 22 of 2021, a Saturday morning, a black BMW drove into a crowd of pedestrians in the northeastern Chinese city of Dalian, leaving five people dead and five injured.

The driver, who was soon arrested, was a man by the name of Liu Dong (刘东), who reportedly purposely drove into the crowd to take “revenge on society” after an investment failure.

In October 2021, Liu Dong was sentenced to death at the Dalian Intermediate People’s Court. Although Liu appealed, the initial ruling was upheld. With approval by the Supreme People’s Court of China (SPC), Liu Dong was executed on April 7th, 2023.

On social media, the execution attracted a lot of attention. One related hashtag, “Dalian BMW Driver Who Drove Into People Executed by Death Penalty” (#大连宝马撞人案司机被执行死刑#), received over 230 million clicks.

“He got what he deserved,” a recurring comment said.

Because the Dalian case is very similar to another incident that happened in January of this year in Guangzhou, many people on Chinese social media asked for an update on that case.

Five people were killed and 13 others were injured in that incident, which also involved a BMW driving into pedestrians at Tianhe Road in Guangzhou on 11 January, 2023. The shocking incident was all over Weibo, where one hashtag related to the topic received over 1.2 billion views at the time. Many hashtags were removed shortly after and are still offline now, three months later.

The horrific incident that happened in Guangzhou earlier in 2023 had many similarities to the Dalian hit-and-run case.

“The Guangzhou driver should be next,” many commenters wrote.

Support for Harsher Sentences

On Chinese social media, it is often those supporting the harshest penalties who seem to be in the majority. In the case of the BMW driver, the majority of comments commend the Chinese legal system for enforcing capital punishment. Regarding the Xuzhou chained mother case, a common sentiment is that the sentences should have been harsher.

Under China’s criminal law, penalties for trafficking women and children range from five years imprisonment to life or even the death penalty. But the maximum prison term for people who buy abducted or trafficked women is only three years.

There have been many discussions about this on social media, where many argue that the punishment should actually be the same regardless if someone sells or buys. Others say that those buying trafficked women or children should also be able to receive the death penalty.

In China, where capital punishment has a centuries-old history, executions are carried out by lethal injection or by shooting and always have to be approved and confirmed by the Supreme People’s Court.

“I’m in favor of the death penalty,” (“支持死刑”) is a recurring comment in discussions about the Dalian hit-and-run case. Looking at social media alone, it seems that an overwhelming majority of commenters support the death penalty in cases such as these.

In 2020, The China Quarterly published a study by Liu (2021) about public support for the death penalty in China. Based on national survey data, the author argues that although there is indeed strong support for the death penalty in China, it is perhaps not as strong as is commonly assumed.

According to the study by Liu, a majority of 68% of China’s citizens are for the death penalty, while 31% are opposed to it. At the same time, the study also showed that most Chinese people would agree to replace the death penalty with life imprisonment without parole (Liu 2021, 541).This sentiment is also reflected in some online discussions.

The level of support for the death penalty varies depending on which factor is given the most weight in the views of individuals. Some emphasize the ‘warning role’ of the death penalty, arguing that it has a deterrent effect. Others consider retribution an important reason to be in favor of the death penalty. Then there are those who think that the death penalty allows offenders to avoid facing the consequences of their crimes, and they suggest that spending life in prison would be a better way to make them pay for what they did.

The idea of capital punishment serving as a warning and deterrent is an important one in China. One study comparing death penalty views in China, Japan, and the US (Jiang et al 2010) found that while retribution is the most significant factor for Americans who support the death penalty, deterrence plays a more important role in Chinese and Japanese views in favor of capital punishment (868).

In the two trending cases, there is some disagreement online on whether or not justice was truly served. There is one thing that virtually everyone agrees on: they hope that the surviving victims and their families will find peace and happiness after everything they have been through.

By Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

References

Jiang, Shanhe, Eric G. Lambert, Jin Wang, Toyoji Saito, Rebecca Pilot. 2010. “Death Penalty Views in China, Japan and the U.S.: An Empirical Comparison.” Journal of Criminal Justice 38.5: 862–869.

Liu, John Zhuang. 2021. “Public Support for the Death Penalty in China: Less from the Populace but More from Elites.” The China Quarterly 246: 527-544.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Food & Drinks

The ‘China-chic Girl’ Image and the Realities of China’s Competitive Food Delivery Market

How did the trendy and cute “China Chic” cartoon image come to symbolize questionable takeout food in China?

Published

4 weeks agoon

January 25, 2025By

Ruixin Zhang

FROM THE WEIBO WATCH PREMIUM NEWSLETTER

“What should we order for dinner?” is a daily dilemma for millions of Chinese consumers in one of the world’s largest food delivery markets. With numerous platforms, cuisines, menus, and discount options, choosing the right takeout—one that is tasty, affordable, and safe—can feel like a daunting task.

But these days, many Chinese people follow a simple rule to identify bad takeout: if your delivery comes in packaging featuring a playful young woman wearing sunglasses, a traditional Peking opera headdress, and holding a fan—often with the bold trendy character “潮” (cháo, meaning “trend”)—it’s likely to be an unhealthy meal with potential food safety risks.

As one netizen joked, “I was so excited for my takeout, only to see this lady on the package and feel my heart sink.” Why does this seemingly cheerful cartoon figure evoke so much distrust and dislike from so many?

China-chic Girl

In 2020, digital illustrator @YUMI created the “China-chic Girl” image in response to a client’s request for a design that embodied the “China-chic” (国潮, guócháo) aesthetic.

China-chic, or guócháo—literally meaning “national tide”—refers to the rise of Chinese domestic (fashion) brands that often incorporate culturally Chinese elements into contemporary designs. This trend emerged as a reflection of growing nationalist sentiment in China, offering a Chinese counterpart to popular Japanese or Korean-inspired styles. From fashion and makeup to milk tea, ‘China-chic’ quickly became a defining element of China’s consumer culture (read more here).

Vlogger @花小雕 dressed up as the “China-chic” girl for Halloween.

However, when YUMI’s client failed to pay, she chose to release the design for free public use. YUMI’s creation—a blend of traditional Peking opera elements and modern sunglasses—struck a chord with its simple yet iconic charm. Its accessibility made it even more appealing, and the China-chic Girl soon became the go-to design for restaurants looking for affordable, visually striking takeout packaging.

On China’s wholesale website 1688, you can find a wide range of cheap takeout packaging with the “China-chic girl” on it.

The China-chic Girl was all the rage, until last fall.

Starting in September, some delivery drivers began exposing filthy kitchen conditions on social media, warning customers to avoid takeout from certain restaurants after witnessing food safety issues and kitchen hazards while waiting for orders.

Over time, people began noticing a pattern: the dirtiest kitchens were often small, non-chain establishments with no physical storefronts—just cramped spaces dedicated solely to takeout. Operating on tight budgets, these businesses often chose the inexpensive China-chic girl packaging to cut costs, unintentionally associating the China-chic girl with unsanitary and unsafe food practices.

As a result, netizens—especially young people who heavily rely on food delivery—started compiling guides to help each other avoid sketchy takeout options. The warning signs? Restaurants offering “cashback for good reviews” or those that lack a proper storefront, often listing only food items instead of a real restaurant name. These red flags point to private kitchens, poorly managed spaces, or even unregulated food safety practices. Additionally, many of these ‘China-chic takeouts’ thrive within the “group-buying” model on food delivery platforms.

No Such Thing As a Free Lunch

The “group-buying” model, popularized by platforms like Temu and its Chinese counterpart Pinduoduo (拼多多), allows users to invite friends, family, or colleagues to purchase a product together at a discounted price.

This strategy has since evolved into a pseudo-group-buying model, where even without inviting others, the group-buying discount is still applied. These discounts are carefully calculated by platforms to ensure that, even at reduced prices, profits can still be made due to the high sales volume.

Both Meituan (美团) and Eleme (饿了么)—the two largest food delivery platforms in China—have adopted this approach by introducing budget-friendly services such as Pinhaofan (拼好饭) and Pintuan (拼团) to target lower-tier markets.

For example, a typical 30 RMB ($4.15) takeout might cost only half that price through these services, with additional platform coupons and new user discounts making it almost irresistibly affordable.

A meal for 7.45 yuan ($1), but how fresh and safe is it?

But, of course, there’s no such thing as a free lunch. As many users have discovered, getting a full meal for under 10 RMB ($1.40) often comes at the expense of quality. These Pinhaofan takeouts commonly feature pre-made dishes with indistinguishable ingredients, flimsy utensils that can’t even scoop rice, a box of suspicious juice full of artificial coloring, low-grade packaging, and, of course, that cheap, once-iconic China-chic design.

A Meme Culture of “Bad Food”

Despite widespread awareness of these issues, the cheap Pinhaofan orders remain incredibly popular. According to Meituan’s second-quarter earnings report, the Pinhaofan service is booming, with order volumes reaching a record high of over 8 million orders per day. Why do people continue to order these potentially unsafe meals despite knowing the risks?

“Low price” has been the keyword for Meituan and the Chinese food delivery market for a long time. In the face of a sluggish economy and rising youth unemployment, online discussions are dominated by concerns over “consumption downgrades” (消费降级), “middle-class poverty” (中产返贫), “youth unemployment” (青年失业率), and “deflation” (通缩).

More and more people are turning to affordable takeout as a quick fix for their everyday struggles, even if the quality leaves much to be desired.

China Chic Girl Takeout

“I’m not stupid; I don’t expect a gourmet feast for 10 yuan ($1.4),” is a common attitude. As wallets run dry and work hours grow longer, health often becomes an afterthought.

This harsh reality, combined with the “lie-flat” mentality embraced by many young people, has turned ‘China-chic takeout’ and ‘Pinhaofan’ into online memes.

These meals have become symbols of resignation and self-deprecating humor among Chinese youth. When someone dares to express dissent or outrage about unchangeable realities—whether personal struggles or broader national policies—they’re often met with tongue-in-cheek pessimistic remarks like, “Have a couple of Pinhaofan meals and you’ll calm down” (“吃两顿拼好饭就老实了”).

Comparing take-out food: how bad is it actually? There’s a meme culture around Pinhaofan takeout food.

This phenomenon reflects a psychological defense mechanism. For young people who know they cannot change their circumstances, who find themselves at the bottom of society enduring immense hardship—even exploitation—they no longer confront failure directly or refer to themselves using the once-common “diaosi” (屌丝, loser).

Instead, they say things like, “Eating Pinhaofan every day makes me feel like I’ve won in life.” Perhaps it’s a bittersweet acceptance, but it’s not defeat.

No One Benefits—Except the Platforms

While memes can be entertaining, the real-world impact of Pinhaofan is far from positive for most involved—except for the platform giants. According to a report by Zhiwei Editorial Department (@知危编辑部), the Pinhaofan service significantly cuts into restaurant owners’ profit margins. Unlike regular takeout orders, where businesses pay a commission based on the final price, Pinhaofan offers a fixed, much lower payout per order, determined by the platform’s pricing categories. This often leaves restaurants with a meager profit margin of just 2-3 RMB ($0.3-$0.4) per order.

To stay afloat, restaurants are forced to cut corners—replacing fresh meats with frozen ones, opting for cheaper ingredients, and, of course, using the cheapest packaging, often taking the “China Chic” route.

So why do restaurants stick with this model?

The answer is simple: survival. On food delivery platforms, restaurant rankings are usually heavily influenced by factors like operational experience and longevity, giving older, established businesses a visibility advantage. This creates a cycle where newcomers struggle to compete.

The Pinhaofan model changes this dynamic by ranking individual dishes rather than entire restaurants. A single hit dish can boost a restaurant’s overall visibility and sales. In China’s highly competitive food delivery market, platform exposure is everything. Platforms often encourage struggling new restaurants to join Pinhaofan, positioning it as an opportunity to gain visibility. Faced with relentless competition and aggressive price wars, restaurants feel they have no choice but to participate, even if it means compromising on quality and profit.

Pinhaofan model: rankings ar based per dish, instead of per restaurant.

For delivery drivers, Pinhaofan presents its own set of challenges. To accommodate its group-order nature, Meituan introduced a “Changpao” (畅跑, or “smooth running”) mode for couriers. Under this system, couriers are assigned multiple Pinhaofan orders—often bundled with regular orders from the same restaurant along the same route—in a single trip, enabling them to deliver 2-3 times the usual number of orders in one go. The promise of “more work, more pay” draws couriers in, but the reality is far less rosy.

As explained by one Chinese blogger (@黑夜之晴天滚雪球), couriers’ per-order income under Changpao is nearly 50% lower than in regular modes. Even with a higher delivery volume, their overall earnings see little improvement. Worse still, regular (non-Pinhaofan) orders included in these bundled deliveries are also paid at the lower Changpao rate.

Couriers have vented their frustrations on social media, labeling Pinhaofan and Changpao as “exploitative.” One courier shared that a single Pinhaofan order earned them just 2.5 RMB ($0.35), and when group discounts were factored in, their earnings dropped to less than 1 RMB ($0.14) per order.

While couriers direct their grievances toward the system, customers are increasingly dissatisfied with the service. Complaints about couriers refusing to deliver Pinhaofan orders upstairs are growing. In some cases, couriers have reportedly even tampered with food to express their anger in a system where resistance feels futile.

For full-time couriers, the situation is even more grueling. Many work seven-day weeks, with at least two mandatory days spent on Changpao mode, leaving them with little choice but to comply with the system’s demands.

Shiba inu having China Chic takeout food. Meme video.

The “China chic girl” has gone from being a playful symbol of pride in domestic products to representing the problems of China’s fast and cheap takeout industry. What once celebrated affordability now highlights cost-cutting, poor quality, and exploitation.

It’s unclear if the memes and discussions around Pinhaofan will eventually bring real change to the situation at hand. But one thing is certain: the once-cute packaging now serves as a reminder of the sacrifices made by customers, restaurants, and delivery drivers in a system that eventually benefits only the platforms.

By Ruixin Zhang

Independently covering digital China for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Society

Explaining the Bu Xiaohua Case: How One Woman’s Disappearance Captured Nationwide Attention in China

This is why Bu Xiaohua’s 13-year disappearance became such a major topic of discussion on Chinese social media.

Published

2 months agoon

December 14, 2024

PREMIUM CONTENT

The story of Bu Xiaohua, a Chinese MA graduate who was reunited with her family after disappearing for 13 years, has recently dominated discussions on Weibo. Her case reveals much more than just the mystery of her disappearance—it highlights systemic failures and the vulnerability of women in rural China. Here, we unpack the key aspects of her story.

Her name is Bu Xiaohua (卜小花), but for the past 13.5 years, she lived a life without that name and without any connection to the person she once was.

The story of this Chinese female MA graduate from Shanxi’s Jinzhong, born on September 1, 1979, who disappeared for over a decade and was recently found living in a village just a 2.5-hour drive from her hometown, has sparked widespread discussion on Weibo and beyond. We previously explained the story in our article here.

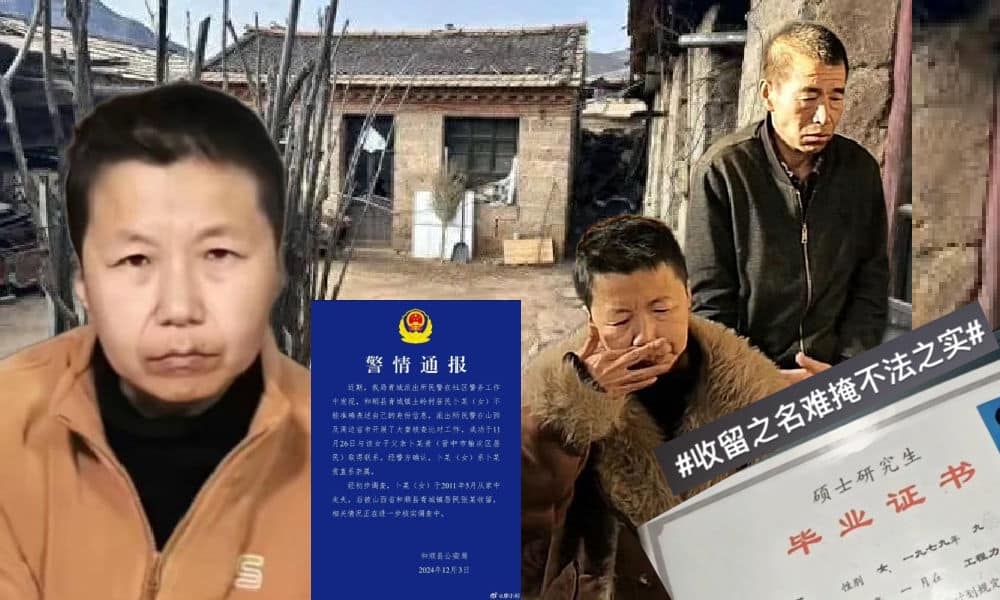

In brief: On November 25, 2024, a woman from Heshun County (和顺县) sought help from volunteer Zhu Yutang (朱玉堂), who focuses on reuniting families with missing loved ones, to trace the origins of her “aunt,” who had been living with her uncle Zhang Ruijun (张瑞军) for over a decade. During this time, they had multiple children together, despite the woman clearly suffering from mental illness.

As volunteer groups and authorities got involved, it was eventually revealed that the woman was Bu Xiaohua (卜小花), an MA graduate from Jinzhong who had disappeared after experiencing a schizophrenic episode in the spring of 2011. Bu was found looking emaciated, bewildered, and unkempt, and was soon reunited with her family, who immediately ensured she received the help she needed. During a medical check-up, she was found to be not only suffering from mental illness but also from malnourishment.

Bu Xiaohua in the Zhang family home.

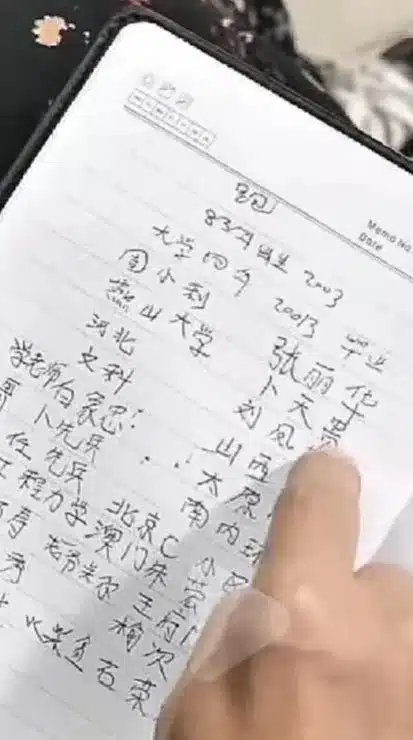

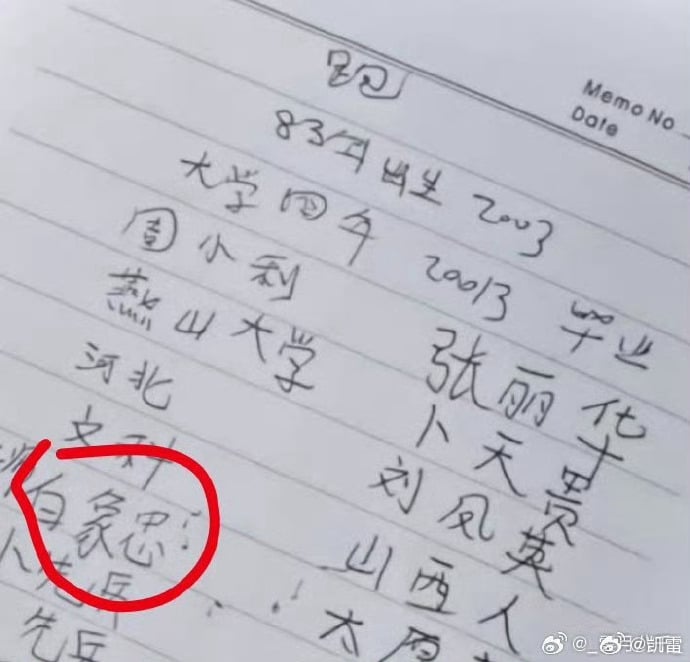

When volunteers first met with Bu, they tried to get her to speak and learn more about her background. Among other things, she also wrote down several clues that led to the discovery of her identity, such as the names of family members. The first thing she wrote down was “run” (跑).

The note by Bu Xiaohua provided many clues about her life prior to being “taken in.”

As discussions about Bu’s disappearance continue, several aspects of this case have become focal points, highlighting the vulnerable position of Bu and many other women like her.

1. “收留”: Was She “Taken In” or Abducted?

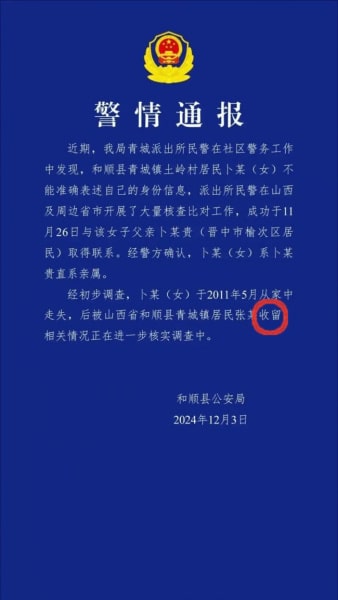

One term that frequently comes up in discussions around Bu Xiaohua’s case is “收留” (shōu liú), meaning “to take in” or “give shelter.”

This term was used in various reports about Bu’s story, including in the first police report of December 3.

Police report of December 3, 2024, using the word “taking in.”

Many netizens pointed out that the initial police statement seemed to frame the situation as an act of human compassion, reflecting the niece’s account of how Ms. Bu allegedly “wandered” into their family home one day. The family claims they reported her to the police but eventually decided to “take her in.”

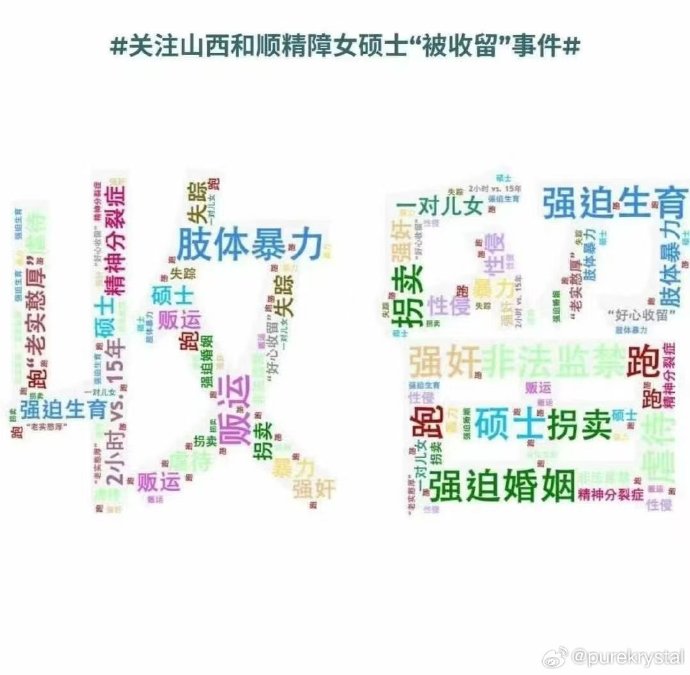

Netizens are outraged by the use of this term, as it glosses over the criminal responsibility of Zhang and his family, who essentially kept Bu Xiaohua away from her own family for over 13 years. They are accused of exploiting her mental illness and inability to consent to marriage or sexual relations, which resulted in multiple children. The exact number is unclear, though rumors suggest she had six children in total, with only two remaining in her care.

The oldest of the two children is already twelve, meaning she must have become pregnant not too long after going missing.

Some commenters have referred to this as “rape-style sheltering” (“强奸型收留”). Was it rape, human trafficking, or illegal detention?

While netizens speculated about the actual crime behind this “taking in” of a mentally ill woman, local police announced they had opened a criminal investigation into suspected illegal acts. Bu’s “husband” has since been detained, and officials are continuing to investigate the case.

No evidence or clues of Bu being trafficked have been found as of now. Investigations into the case reveal that Bu – displaying signs of mental illness according to witnesses – was alone when she walked around neighboring villages for at least ten days in July and August of 2011, some weeks after she disappeared from her home.

Bu and “husband” Zhang at her reunion with family.

The hashtags “Taking In” (#收留#) and “‘Taking In’ Shouldn’t Be Used as a Cover for Unlawful Realities” (#收留之名难掩不法之实#) have been used by netizens to protest the phrase’s use.

Online image showing all kinds of weords, from ‘human trafficking’ to ‘violence’ to shape the characters for the neutral word of ‘taking in.’

Meanwhile, some reports on the misuse of the term have been censored. The Weibo hashtag “Taking In the Female MA Graduate” (#收留女硕士#) has been taken offline and comes up with a “Sorry, the content of this topic is not displayed” message. A QQ News article titled “Female Master’s Graduate Missing for 13 Years Has Given Birth to a Son and a Daughter; The Person Who ‘Took Her In’ Responds: ‘I Didn’t Detain or Hit Her'” (“女硕士走失13年已生育一儿一女,“收留者”本人回应”) also now leads to a ‘404 page,’ indicating it has been removed.

Critics like Lawyer Zhao (@披荆斩棘赵律师), who has actively commented on this case, believe that Bu’s “husband” and his family never made any real effort to help her find her own family. They speculate that the family only agreed to let volunteers get involved because Bu’s childbearing value had long been exhausted, or because she was aging and they no longer wanted to care for her.

Zhang’s niece, whose request to volunteers initially brought this story to light, has also become an increasingly controversial figure. She recently hosted a livestream in which she claimed that the Zhang family had actually taken good care of Bu, describing her as a “good-for-nothing” who neither did housework nor fed her own children. She also defended her impoverished and disabled unlce Zhang, claiming the family is not as bad as the public says.

“Let her experience being ‘taken in’ by another family and see how she feels,” some top commenters suggested in response.

2. Lacking Law Enforcement: Systematic Failures Exposed

The outrage over the term “taking in” is directly tied to anger over inadequate law enforcement regarding the protection of women in rural China.

Years ago, local police in Heshun County, where Zhang’s family lives, were already aware of a mentally unstable woman being “taken into” a man’s home and giving birth to his children. After all, both children had a hukou (household registration). Chinese media report that police officers visited the home multiple times and allegedly continued efforts to search for her family, which indicates they understood her situation. People wonder how they could let this go on, given Zhang’s continued sexual relations with her—wouldn’t that constitute rape?

Female commenter and author Zheng Yuchuan (@郑渝川) suggested that Bu’s case is particularly troubling because of systematic failure at all levels. She wrote:

“Despite population censuses, pandemic prevention measures like mass nucleic acid testing and vaccinations, as well as the issuance of birth certificates, household registrations, and school admission procedures for the two children—every single step was carried out flawlessly. Isn’t this the biggest joke within the current institutional system?”

Although there are reports emphasizing the continued efforts of the police to find Bu’s family, many netizens aren’t convinced: “Why is it that the police took blood samples and conducted facial recognition comparisons, yet after 13 years, they achieved nothing? Meanwhile, a volunteer, using just a bit of intelligence, managed to make her write down some names, and this bizarre case was solved.”

Law blogger Zhang San (@张三同学) commented: “A single crime pollutes a river; a single act of unjust law enforcement pollutes the entire water source.”

3. A Brilliant Mind: Bu Xiaohua’s Academic Achievements

Another recurring topic is Bu’s academic achievements before her life with the Zhang family. Bu was a student in Yanshan University’s (燕山大学) Mechanics and Engineering program, a prestigious major.

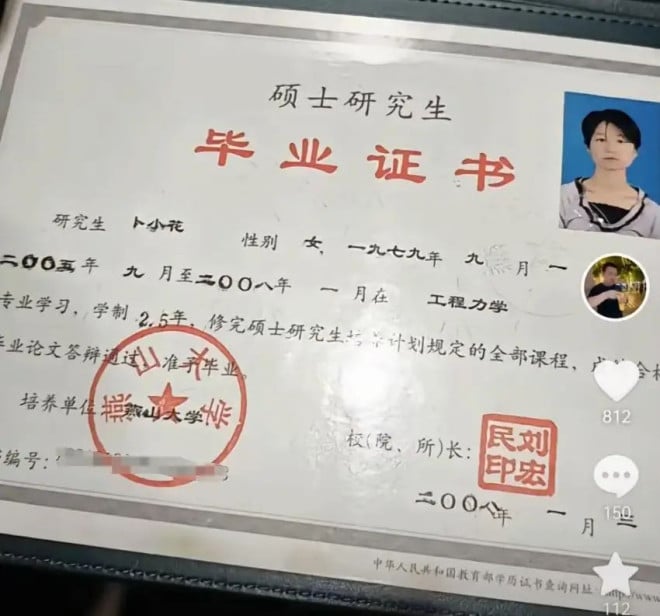

In 2004, she wrote a thesis titled “Temperature Field of a Thin Plate with Curved Cracks During Electrothermal Crack Arrest” (带有曲线裂纹薄板电热止裂时的温度场). Her 2006 thesis was “Small Bending Deformation of an Elastic Thin Plate Under Continuous Transverse Flow-Around Conditions” (不间断横向绕流条件下弹性薄板的小弯曲变形). She obtained her MA degree in 2008.

Bu had planned to continue in academia, but due to an expired ID card, she was unable to register for her Ph.D. exam—a setback that marked the beginning of her rapidly deteriorating mental health. This eventually led to her leaving her home one day in 2011, vanishing without a trace, and ending up in her dire situation with the Zhang family.

Bu Xiaohua’s diploma

Her education is significant to the story in many ways. First, it serves as an important bridge to her past. One of her former professors, the 82-year-old Bai Xiangzhong (白象忠), was one of the names Bu first wrote on a note when volunteers from the missing persons organization came to her house and asked her about her life.

The name of Professor Bai Xiangzhong is one of the names Bu wrote down on a memo in the presence of volunteers trying to learn more about her life.

In recent news, it became known that Bai Xiangzhong learned of Bu’s story and was moved to tears upon hearing about her circumstances.

Bu’s education is also an important part of her identity. Recent videos showed Bu reading a book and pushing back her glasses—which she hadn’t had for 13.5 years—as if it was the most normal thing in the world.

Recent videos showed Bu reading a book and pushing back her glasses—which she hadn’t had for 13.5 years—as if it was the most normal thing in the world.

One popular Weibo blogger (@我不是谦哥儿) wrote:

“More than the Master’s degree she obtained years ago, it’s this natural skill [the way she reads and pushes back her glasses] in which we can directly observe and vividly feel the life she had. We can feel that, if it were not for the dusky farmhouse in the mountainous area where she got trapped, there would have been an entirely different possibility [for her life].”

But her education is also significant in other ways. It shows that it is not just low-income, less-educated, rural women who can become victims of rape and human trafficking, but that even women with a university degree can end up in such situations.

4. Bu Xiaohua’s Case: A Reflection of Larger Social Issues

In the end, the story of Bu Xiaohua is attracting so much attention because she represents much more than just herself.

One of the most well-known stories similar to hers is that of Xiao Huamei (小花梅), the mother of eight children who was found tied to a shed in Xuzhou in 2022. After her story became a major trending topic on Chinese social media, local authorities launched a thorough investigation and uncovered the woman’s true identity. They found that she had been a victim of human trafficking back in 1998.

Like Bu, Xiao Huamei also suffered from mental illness. And similar to Bu’s case, local authorities failed to step in. The family received subsidies, and local officials approved the marriage between the mentally ill woman and her husband, Dong Zhimin, who was later sentenced to prison for his involvement in the human trafficking case.

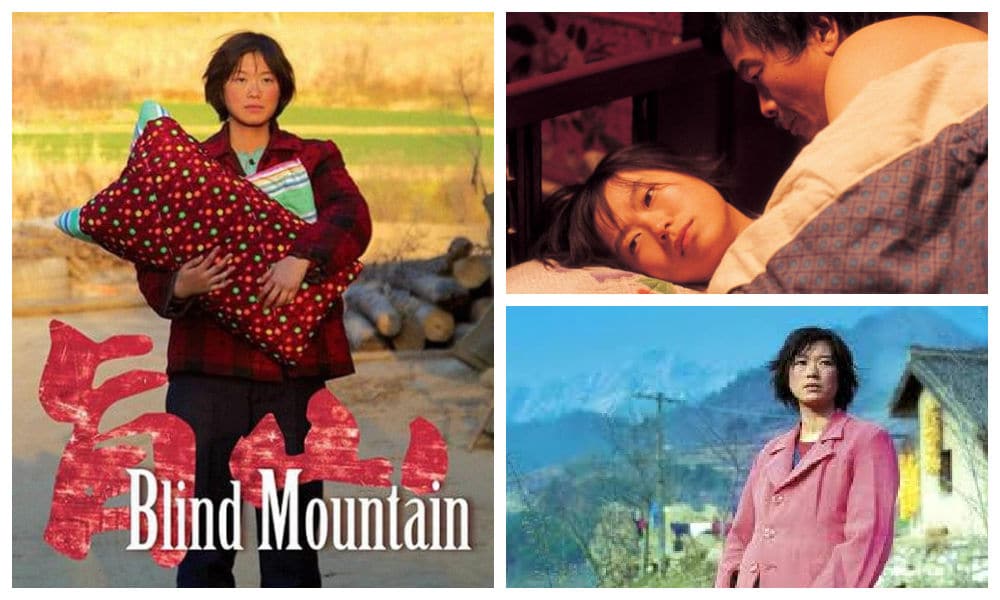

This all brings back associations with the Chinese film Blind Mountain (盲山, 2007). Directed by Li Yang (李杨), the movie revolves around Bai Xuemei (白雪梅), a recent college graduate who is tricked into traveling to a remote mountain village under the pretense of securing a job. Once there, she is drugged, kidnapped, and sold into a forced marriage with a rural farmer. Trapped in the isolated and impoverished village, she faces constant physical and psychological abuse from her “husband,” his family, and even the local community, who see her captivity as normal or necessary. Despite multiple attempts to escape, she is repeatedly caught and encounters indifference or complicity from those around her, including the police. She is only rescued years later.

From Blind Mountain (2007).

Films such as Blind Mountain and the 2022 case of Xiao Huamei have helped create more awareness of the vulnerable position of Chinese women in rural areas, particularly those dealing with mental or physical disabilities. Last year, a marriage in Henan was denied after a local official found the woman, who was deaf and mute, had not learned sign language and could not write (read more).

But the problem persists. China, particularly its rural villages, faces a shortage of women stemming from the decades-long one-child policy and a traditional preference for boys. This has been further exacerbated by women migrating out of villages in search of better prospects. As a result, many rural single men are unable to marry, especially when they face additional challenges such as poverty or disability. Since marriage and children are considered social norms, these men and their families are often willing to take drastic measures. This situation has fueled the human trafficking of women for forced marriage in China since the 1980s.

“Why not re-release Blind Mountain?” some wonder. “It feels so relevant today.”

As for Bu, she is currently doing well given the circumstances. Her brother, who searched for her for so many years, is determined to take care of his sister. “My little sister is the treasure of our entire family,” he recently said. “Every day that I am on this earth is a day that I will take care of her.”

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

What’s on Weibo Chapters

Subscribe

From Weibo to RedNote: The Ultimate Short Guide to China’s Top 10 Social Media Platforms

Collective Grief Over “Big S”

Tuning Into the Year of the Snake

The ‘China-chic Girl’ Image and the Realities of China’s Competitive Food Delivery Market

From “Public Megaphone” to “National Watercooler”: Casper Wichmann on Weibo’s Role in Digital China

Our Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Why Chinese Hit Movie “Her Story” is ‘Good Stuff’: Stirring Controversy and Celebrating Female Perspectives

Chiung Yao’s Suicide Farewell Letter: An English Translation

12-Year-Old Girl from Shandong Gets Infected with HPV: Viral Case Exposes Failures in Protecting Minors

Breaking the Taboo: China’s Sanitary Pad Controversy Sparks Demand for Change

Weibo Watch: Christmas in China Is Everywhere and Nowhere

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

Weibo Watch: China’s Online Feminism Is Everywhere

Story of Chinese Female MA Graduate Going Missing for 13 Years Sparks Online Storm

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight10 months ago

China Insight10 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music11 months ago

China Music11 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Insight12 months ago

China Insight12 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Digital9 months ago

China Digital9 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI