China Arts & Entertainment

Weibo Super Stars: Chinese Celebrities With Most Weibo Followers

They are China’s super stars and have the largest online fanbase in the world. What’s on Weibo has compiled a top 10 of people with the most followers on Sina Weibo.

Published

9 years agoon

They are China’s super stars and have the largest online fan base in the world. What’s on Weibo has compiled a top 10 of people with the most followers on Sina Weibo.

The Sina Weibo social media platform is often called the “Chinese Twitter”. Although Weibo is not really similar to Twitter, it does have the same ‘follower-followee’ system. Weibo users can become a ‘fan’ (粉丝) of another Weibo user, without having to be followed back. Being someone’s ‘fan’ means their posts will show up on your timeline, which you can like, share and comment on.

This is a list of celebrities from mainland China with the biggest fan base. In comparison: the celebrities with the most followers on Twitter are Katy Perry (75 million), Justin Bieber (67 million), and Barack Obama (63 million). The top two of China’s Weibo celebrities have over 78 and 77 million ‘followers’: the largest online fanbase in the world.

1. Yao Chen 姚晨

78.168.835 followers.

Yao Chen (1976) is a Chinese actress and Weibo celebrity, who was mentioned as the 83rd most powerful woman in the world by Forbes magazine. She is also called ‘China’s answer to Angelina Jolie’ (Telegraph).

Yao Chen is not necessarily China’s number one actress, but she was one of the first celebrities to share her personal life on Weibo since 2009, and interact with her fans. On Weibo, she talks about her everyday life, family, news-related issues, work, and fashion. She posts personal pictures every day. The combination of her popularity due to acting work, combined with her frequent Weibo updates and closeness to her fans, have made Yao Chen the number one Weibo celebrity.

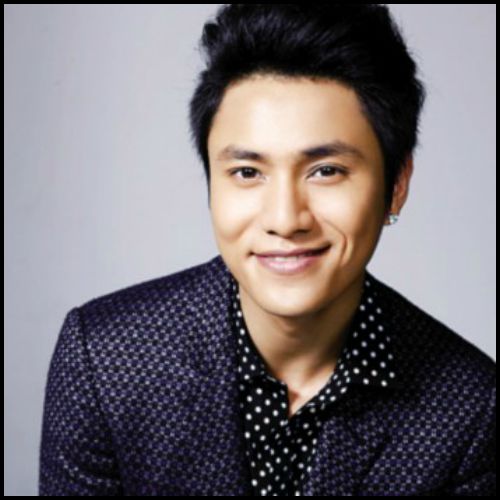

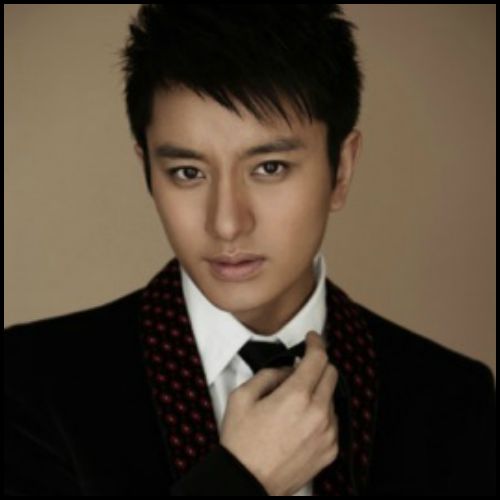

2. Chen Kun 陈坤

77.979.847 followers.

Chinese actor and singer Chen Kun (1979, Chongqing) is known for his roles in, amongst others, Painted Skin and Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress. Chen Kun is not only popular because of his acting work, but also for his looks – he is known to have a large gay fanbase.

3. Zhao Wei 赵薇

73.311.919 followers.

Vicky Zhao (1976) is a Chinese film star, singer, entrepreneur and director. She is also known for her work as ambassador for various brands, which has added to her wealth.

Zhao Wei is the world’s wealthiest working actress. Together with actresses Zhang Ziyi, Zhou Xun and Xu Jinglei, she belongs to China’s ‘Four Dan Actresses’ (四大花旦): the four greatest actresses of mainland China.

Zhao Wei regularly updates her Weibo, where she posts about her work as an actress, her photoshoots, and her ambassador work for good causes. In the recent pictures below, she visits a hospital for children with leukaemia.

4. Xie Na 谢娜

72.962.003 followers.

Xie Na (1981), also nicknamed ‘Nana’, is a popular singer, actress and designer. She is also the co-host of ‘Happy Camp‘ (快乐大本管), one of China’s most popular variety TV shows. She is the colleague of He Jiong, the number 5 in this list.

Xie Na stars in many popular Chinese films and television series. She has also released several albums, founded a personal clothing line, and published two books.

Before getting married to Chinese singer Zhang Jie, Xie Na was in a 6-year relationship with her colleague Liu Ye, who is on number 7 of this list.

5. He Jiong 何炅

69.567.457 followers.

He Jiong has been the host of China’s popular Happy Camp TV show for over ten years. He is also a singer, actor and an Arabic teacher in Beijing Foreign Studies University.

‘Happy Camp’ (快乐大本馆) is a prime time variety show aired by Hunan TV. It is one of China’s most popular TV shows. With a viewership of tens of millions, it often holds the first place in China’s total viewing rating.

[showad block=2]

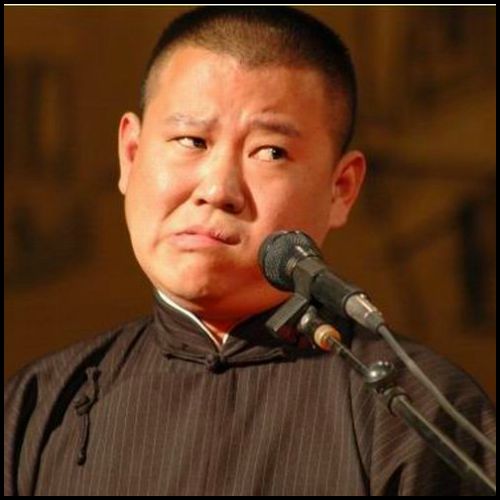

6. Guo Degang 郭德纲

62.386.148 followers.

Guo Degang is a Chinese comedian (1973) and known for his ‘xiangsheng‘ (相声), a traditional Chinese comedic performance in the form of a dialogue between two performers.

One of Guo Degang’s Weibo posts caused controversy in 2013, when the comedian posted a poem about karma the day after Beijing TV director Wang Xiaodong passed away.

Guo Degang recently posted on Weibo about stepping into the wine business.

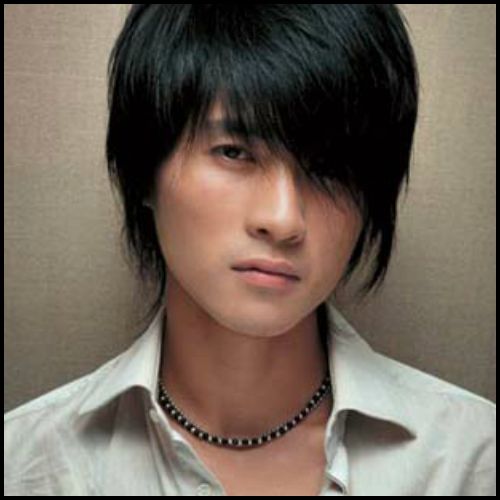

7. Liu Ye 刘烨

48.189.408 followers.

Liu Ye (1978) is a famous Chinese actor, who is known for taking on difficult roles. He played a young homosexual man in Lan Yu and starred opposite Meryl Streep in the Hollywood film Dark Matter.

The actor is currently a contestant in China’s popular reality show ‘Where Are We Going, Dad?‘, which is now a recurring topic in his Weibo posts.

8. Han Han 韩寒

41.933.102 followers.

Famous Chinese blogger, best-selling writer and race-car driver Han Han (1982) is one of the most influential people on Weibo, and was even named one of the most influential people in the world by Time magazine in 2010.

Han Han does not post daily updates on his Weibo, but he is known for addressing sensitive topics. Not long ago, he shared his thoughts on China not allowing single women to freeze their eggs.

9. Jia Nailiang 贾乃亮

41.310.313 followers.

Jia Nailiang (1984, Harbin) is an actor who has starred in TV series since he was a child. He has starred in over 30 TV series in the past 10 years. He is married to award-winning actress Li Xiaolu.

10. Fan Bingbing 范冰冰

38.591.597 followers.

Fan Bingbing (1981) is one of China’s most famous fashion icons and actresses, known for, amongst others, Lost in Beijing, Chongqing Blues and X-Men: Days of Future Past.

Fan Bingbing is the 4th highest-paid actress in the world.

By Manya Koetse

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

©2015 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Memes & Viral

How Ne Zha 2’s Shen Gongbao Became Known as the Ultimate “Small-Town Swot”

Published

5 days agoon

March 1, 2025

PART OF THIS TEXT COMES FROM THE WEIBO WATCH PREMIUM NEWSLETTER

Over the past few weeks, the Chinese blockbuster Ne Zha 2 has been trending on Weibo every single day. The movie, loosely based on Chinese mythology and the Chinese canonical novel Investiture of the Gods (封神演义), has triggered all kinds of memes and discussions on Chinese social media (read more here and here).

One of the most beloved characters is the leopard demon Shen Gongbao (申公豹). While Shen Gongbao was a more typical villain in the first film, the narrative of Ne Zha 2 adds more nuance and complexity to his character. By exploring his struggles, the film makes him more relatable and sympathetic.

In the movie, Shen is portrayed as a sometimes sinister and tragic villain with humorous and likeable traits. He has a stutter, and a deep desire to earn recognition. Unlike many celestial figures in the film, Shen Gongbao was not born into privilege and never became immortal. As a demon who ascended to the divine court, he remains at the lower rungs of the hierarchy in Chinese mythology. He is a hardworking overachiever who perhaps turned into a villain due to being treated unfairly.

Many viewers resonate with him because, despite his diligence, he will never be like the gods and immortals around him. Many Chinese netizens suggest that Shen Gongbao represents the experience of many “small-town swots” (xiǎozhèn zuòtíjiā 小镇做题家) in China.

“Small-town swot” is a buzzword that has appeared on Chinese social media over the past few years. According to Baike, it first popped up on a Douban forum dedicated to discussing the struggles of students from China’s top universities. Although the term has been part of social media language since 2020, it has recently come back into the spotlight due to Shen Gongbao.

“Small-town swot” refers to students from rural areas and small towns in China who put in immense effort to secure a place at a top university and move to bigger cities. While they may excel academically, even ranking as top scorers, they often find they lack the same social advantages, connections, and networking opportunities as their urban peers.

The idea that they remain at a disadvantage despite working so hard leads to frustration and anxiety—it seems they will never truly escape their background. In a way, it reflects a deeper aspect of China’s rural-urban divide.

Some people on Weibo, like Chinese documentary director and blogger Bianren Guowei (@汴人郭威), try to translate Shen Gongbao’s legendary narrative to a modern Chinese immigrant situation, and imagine that in today’s China, he’d be the guy who trusts in his hard work and intelligence to get into a prestigious school, pass the TOEFL, obtain a green card, and then work in Silicon Valley or on Wall Street. Meanwhile, as a filial son and good brother, he’d save up his “celestial pills” (US dollars) to send home to his family.

Another popular blogger (@痴史) wrote:

“I just finished watching Ne Zha and my wife asked me, why do so many people sympathize with Shen Gongbao? I said, I’ll give you an example to make you understand. Shen Gongbao spent years painstakingly accumulating just six immortal pills (xiāndān 仙丹), while the celestial beings could have 9,000 in their hand just like that.

It’s like saving up money from scatch for years just to buy a gold bracelet, only to realize that the trash bins of the rich people are made of gold, and even the wires in their homes are made of gold. It’s like working tirelessly for years to save up 60,000 yuan ($8230), while someone else can effortlessly pull out 90 million ($12.3 million).In the Heavenly Palace, a single meal costs more than an ordinary person’s lifetime earnings.

Shen Gongbao seems to be his father’s pride, he’s a role model to his little brother, and he’s the hope of his entire village. Yet, despite all his diligence and effort, in the celestial realm, he’s nothing more than a marginal figure. Shen Gongbao is not a villain, he is just the epitome of all of us ordinary people. It is because he represents the state of most of us normal people, that he receives so much empathy.”

In the end, in the eyes of many, Shen Gongbao is the ultimate small-town swot. As a result, he has temporarily become China’s most beloved villain.

By Manya Koetse, with contributions by Wendy Huang

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

China ACG Culture

Beyond the Box Office: What’s Behind Ne Zha 2’s Success?

The impact of Ne Zha 2 goes beyond box office figures—yet, in the end, it’s the numbers that matter most.

Published

7 days agoon

February 27, 2025

FROM THE WEIBO WATCH PREMIUM NEWSLETTER

These days, everybody is talking about Ne Zha 2 (哪吒2:魔童闹海), the recent hit film about one of China’s most legendary mythological heroes. With its spectacular visuals, epic battles, funny characters, dragons and deities, and moving scenes, the Chinese blockbuster animation is breaking all kinds of records and has gone from the major hit of this year’s Spring Festival film season to the 7th highest-grossing movie of all time and, with its 13.8 billion yuan ($1.90 billion USD) box office success, now also holds the title of the most successful animated film ever worldwide.

But there is so much more behind this movie than box office numbers alone. There is a collective online celebration surrounding the film, involving state media, brands, and netizens. On Weibo, a hashtag about the movie crossing the 10 billion yuan ($1.38 billion) milestone (#哪吒2破100亿#) has been viewed over a billion times. Social media timelines are filled with fan art, memes, industry discussions, and box office predictions.

The success of Ne Zha 2 is not just a win for China’s animation industry but for “Made in China” productions as a whole. Some argue that Ne Zha‘s triumph is not just cultural but also political, reinforcing China’s influence on the global stage and tying it to the ongoing US-China rivalry: after growing its power in military strength, technology, and AI, China is now making strides in cultural influence as well.

In a recent Weibo post, state broadcaster CCTV also suggested that Hollywood has lost its monopoly over the film industry and should no longer count on the Chinese market—the world’s second-largest movie market—for its box office dominance.

Various images from “Ne Zha 2” 哪吒2:魔童闹海

The success of Ne Zha 2 mainly resonates so deeply because of the past failures and struggles of Chinese animation (donghua 动画). For years, China’s animation industry struggled to compete with American animation studios and Japanese anime, while calls grew louder to find a uniquely Chinese recipe for success—to make donghua great again.

🔹 The Chinese Animation Dream

A year ago, another animated film was released in China—and you probably never heard of it. That film was Ba Jie (八戒之天蓬下界), a production that embraced Chinese mythology through the story of Zhu Bajie, the half-human, half-pig figure from the 16th-century classic Journey to the West (西游记). Ba Jie was a blend of traditional Chinese cultural elements with modern animation techniques, and was seen as a potential success for the 2024 Spring Festival box office race. It took eight years to go from script to screen.

But it flopped.

The film faced numerous setbacks, including significant production delays in the Covid years, limited showtime slots in cinemas, and, most importantly, a very cold reception from the public. On Douban, China’s biggest film review platform, many top comments criticized the movie’s unpolished animation and special effects, and complained that this film—like many before it—was yet another Chinese animation retelling a repetitive story from Journey to the West, one of the most popular works of fiction in China.

“Another mythological character, the same old story,” some wrote. “We’re not falling for low-quality films like this anymore.”

The frustration wasn’t just about Ba Jie—it was about China’s animation industry as a whole. Over the past decade, the quality of Chinese animation films has become a much-discussed topic on social media in China—sometimes sparked by flops, and other times by hits.

Besides Ba Jie, one of those flops was the 2018 The King of Football (足球王者), which took approximately 60 million yuan ($8.8 million) to make, but only made 1.8 million yuan ($267,000) at the box office.

Both Ba Jie, which took years to reach the screen, and King of Football, a high-budget animation, ended up as flops.

One of those successes was the 2019 first Ne Zha film (哪吒之魔童降世), which became China’s highest grossing animated film, or, of the same year, the fantasy animation White Snake (白蛇:缘起), a co-production between Warner Bros and Beijing-based Light Chaser Animation (also the company behind the Ne Zha films). These hits

showed the capabilities and appeal of made-in-China donghua, and sparked conversations about how big changes might be on the horizon for China’s animation industry.

“The only reason Chinese people don’t know we can do this kind of quality film is because we haven’t made any good stories or good films yet,” White Snake filmmaker Zhao Ji (赵霁) said at the time: “We have the power to make this kind of quality film, but we need more opportunities.”

More than just entertainment, China’s animated films—whether successes or failures—have come to symbolize the country’s creative capability. Over the years, and especially since the widespread propagation of the Chinese Dream (中国梦)—which emphasizes national rejuvenation and collective success—China’s ability to produce high-quality donghua with a strong cultural and artistic identity has become increasingly tied to narratives of national pride and soft power. A Chinese animation dream took shape.

🔹 The “Revival” of China’s Animation Industry

A key part of China’s animation dream is to create a 2.0 version of the “golden age” of Chinese animation.

This high-performing era, which took place between 1956 and 1965, was led by the Shanghai Animation Film Studio. While China’s leading animators were originally inspired by American animation (including Disney’s 1937 Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs), as well as German and Russian styles, they were committed to developing a distinctly Chinese animation style—one that incorporated classical Chinese literature, ink painting, symbolism, folk art, and even Peking opera.

Some of the most iconic films from this era include The Conceited General (骄傲的将军, 1956), Why Crows Are Black (乌鸦为什么是黑的, 1956), and most notably, Havoc in Heaven (大闹天宫, 1961 & 1964). Focusing on the legendary Monkey King, Sun Wukong (孙悟空), Havoc in Heaven remains one of China’s most celebrated animated films. On Douban, users have hailed it as “the pride of our domestic animation.”

One of China’s most renowned animation masters, Te Wei (特伟), once explained that the flourishing of China’s animation industry during this golden era was made possible by state support, a free creative atmosphere, a thriving production system, and multiple generations of animators working together at the studio.

Still from Havoc in Heaven 大闹天宫 via The Paper.

➡️ So what happened to the golden days of Chinese animation?

The decline of this golden era was partly due to the political turmoil of the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). While there was a second wave of successful productions in the late 1970s and 1980s, the industry lost much of its ‘magic touch’ in the 1990s and 2000s. During this period, Chinese animation studios were pressured to prioritize commercial value, adhere to strict content guidelines, and speed up production to serve the rising domestic TV market—while also taking on outsourcing work for overseas productions.

As the quality and originality of domestic productions lagged behind, the market came to be dominated by imported (often pirated) foreign animations. Japanese series like Astro Boy, Doraemon, and Chibi Maruko-chan became hugely influential among Chinese youth in the 1990s. The strong reaction in China to the 2024 death of Japanese manga artist Akira Toriyama, creator of Dragon Ball, also highlighted the profound impact of Japanese animation on the Chinese market.

This foreign influence also changed viewers’ preferences and aesthetic standards, and many Chinese animations adopted more Japanese or American styles in their creations.

However, this foreign ‘cultural invasion’ was not welcomed by Chinese authorities. As early as 1995, President Jiang Zemin reminded the Shanghai Animation Film Studio of the ideological importance of animation, emphasizing that China needed its “own animated heroes” to serve as “friends and examples” for Chinese youth.

By the early 2010s, the revitalization and protection of China’s animation industry became a national priority. This was implemented through various policies and incentives, including government funding, tax reductions and exemptions for Chinese animation companies, national animation awards, stipulations for the number of broadcasted animations that must be China-made. Additionally, there was an increased emphasis on animation as a tool for cultural diplomacy, focusing on how Chinese animation should reflect national values and history while maintaining global appeal.

It’s important to note that the so-called ‘rejuvenation’ of Chinese animation is not just a cultural and ideological project, there are economic motives at stake too: China’s animation industry is a multi-billion dollar industry.

🔹 “Are We Ne Zha or the Groundhogs?”

The huge success of Ne Zha 2 is seen as a new milestone for Chinese animation and as inspiration for audiences. The film took about five years to complete, reportedly involving 140 animation studios and over 4,000 staff members. The film was written and overseen by director Yang Yu (杨宇), better known as Jiaozi (饺子).

The story is all based on Chinese mythology, following the tumultuous journey of legendary figures Nezha (哪吒) and Ao Bing (敖丙), both characters from the 16th-century classic Chinese novel Investiture of the Gods (Fengshen Yanyi, 封神演义). Unlike Ba Jie or other similar films, the narrative is not considered repetitive or cliché, as Ne Zha 2 incorporates various original interpretations and detailed character designs, even showcasing multiple Chinese dialects, including Sichuan, Tianjin, and Shandong dialects.

One of the film’s unexpected highlights is its clan of comical groundhogs. In this particularly popular scene, Nezha engages in battle against a group of groundhogs (土拨鼠), led by their chief marmot (voiced by director Jiaozi himself). Amid the fierce conflict, most of the groundhogs are hilariously indifferent to the fight itself; instead, they are focused on protecting their soup bowls and continuing to eat—until they are ultimately hunted down and captured.

Nezha and the clan of groundhogs.

Besides fueling the social media meme machine, the groundhog scene actually also sparked discussions about social class and struggle. Some commentators began asking, “Are we Ne Zha or the groundhogs?”

Several blogs, including this one, argued that while many Chinese netizens like to identify with Nezha, they are actually more like the groundhogs; they don’t have powerful connections nor super talents. Instead, they are hardworking, ordinary beings, struggling to survive as background figures, positioned at the bottom of the hierarchy.

One comment from a film review captured this sentiment: “At first, I thought I was Nezha—turns out, I’m just a groundhog” (“开局我以为自己是哪咤,结果我是土拨鼠”).

The critical comparisons between Nezha and the groundhogs became politically sensitive when a now-censored article by the WeChat account Fifth Two-Six District (第五二六区) suggested that many Chinese people are so caught in their own information bubbles and mental frameworks that they fail to grasp how the rest of the world operates. The article said: “The greatest irony is that many people think they are Nezha—when in reality, they’re not even the groundhogs.”

While some see a parallel between Nezha’s struggles and their own hardships, others interpret the film’s success as a symbol of China’s rise on the global stage—particularly because the story is so deeply rooted in Chinese culture, literature, and mythology. This has led to an alternative perspective: rather than remaining powerless like the groundhogs, perhaps China—and its people—are transforming into the strong and rebellious Nezha, taking control of their destiny and rising as a global force.

Far-fetched or not, it’s an idea that continues to surface online, along with many other detailed analyses of the film. The nationalist Chinese social media blogger “A Bad Potato” (@一个坏土豆) recently wrote in a Weibo post:

“We were once the groundhog, but today, nobody can make us kneel!” (“我们曾经是土拨鼠,但是今天,没有任何人可以让我们跪下!”)

In another post, the blogger even dragged the Russia-Ukraine war into the discussion, arguing that caring too much about the powerless “groundhogs,” those struggling to survive, does not serve China’s interest. He wrote:

“(..) whether Russia is righteous or evil does not concern me at all. I only care about whether it benefits our great rejuvenation—whoever serves our interests, I support. Only the “traitors” speak hypocritically about love and justice. Speaking about freedom and democracy that we don’t even understand, they wish Russia collapses tomorrow but don’t care if that would lead to us being surrounded by NATO. So, in the end—are we Ne Zha, or are we the groundhog?”

One line from the film that has gained widespread popularity is: “If there is no path ahead, I will carve one out myself!” (“若前方无路,我就踏出一条路!”). Unlike the more controversial groundhog symbolism, this phrase resonates with many as a reflection not only of Nezha’s resilience but also of the determination that has been driving China’s animation industry forward.

The story of Ne Zha 2 goes beyond box office numbers—it represents the global success of Chinese animation, a revival of its golden era, and China’s growing cultural influence. Yet, paradoxically, it’s also all about the numbers. While the vast majority of its earnings come from the domestic market, Ne Zha 2 is still officially a global number-one hit. More than its actual reach worldwide, what truly matters in the eyes of many is that a Chinese animation has managed to surpass the US and Japan at the box office.

While the industry still has room to grow and many markets to conquer, this milestone proves that part of the Chinese animation dream has already come true. And with Ne Zha 3 set for release in 2028, the journey is far from over.

Want to read more on Ne Zha 2? Also check out the Ne Zha 2 buzz article by Wendy Huang here and our related Weibo word of the week here.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Some of the research referenced in this text can also be found in an article I published in 2019: The Chinese Animation Dream: Making Made-in-China ‘Donghua’ Great Again. For further reading, see:

►Du, Daisy Yan. 2019. Animated Encounters: Transnational Movements of Chinese Animation, 1940s-1970s. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

►Lent, John A. and Xu Ying. 2013. “Chinese Animation: A Historical and Contemporary Analysis.” Journal of Asian Pacific Communication 23(1): 19-40.

►Saito, Asako P. 2017. “Moe and Internet Memes: The Resistance and Accommodation of Japanese Popular Culture in China.” Cultural Studies Review 23(1), 136-150.

🌟 Attention!

For 11 years, What’s on Weibo has remained a fully independent platform, driven by my passion and the dedication of a small team to provide a window into China’s digital culture and online trends. In 2023, we introduced a soft paywall to ensure the site’s sustainability. I’m incredibly grateful to our loyal readers who have subscribed since then—your support has been invaluable.

But to keep What’s on Weibo thriving, we need more subscribers. If you appreciate our content and value independent China research, please consider subscribing. Your support makes all the difference.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

What’s on Weibo Chapters

Subscribe

“Li Jingjing Was Here”: Chinese Netizens React to Rumors of “Chinese Soldiers” in Russia

How Ne Zha 2’s Shen Gongbao Became Known as the Ultimate “Small-Town Swot”

Beyond the Box Office: What’s Behind Ne Zha 2’s Success?

Ne Zha 2: Making Donghua Great Again

The Unstoppable Success of Ne Zha 2: Breaking Global Records and Sparking Debate on Chinese Social Media

Our Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Why Chinese Hit Movie “Her Story” is ‘Good Stuff’: Stirring Controversy and Celebrating Female Perspectives

Chiung Yao’s Suicide Farewell Letter: An English Translation

Breaking the Taboo: China’s Sanitary Pad Controversy Sparks Demand for Change

12-Year-Old Girl from Shandong Gets Infected with HPV: Viral Case Exposes Failures in Protecting Minors

Weibo Watch: Christmas in China Is Everywhere and Nowhere

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

Weibo Watch: China’s Online Feminism Is Everywhere

Story of Chinese Female MA Graduate Going Missing for 13 Years Sparks Online Storm

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight10 months ago

China Insight10 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music11 months ago

China Music11 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Insight12 months ago

China Insight12 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Digital9 months ago

China Digital9 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI