Featured

Weibo Watch: Explosive Material

From nationalist influencers to the Handan murder case, Chinese social media was ablaze with more explosive topics this week than the Yanjiao blast alone.

Published

10 months agoon

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #25

This week’s newsletter:

◼︎ 1. Editor’s Note – Explosive material

◼︎ 2. What’s Been Trending – A closer look at the featured stories

◼︎ 3. What More to Know – Five bit-sized trends

◼︎ 4. What’s the Drama – Top TV to watch

◼︎ 5. What Lies Behind – Justice & social neglect in the Handan murder case

◼︎ 6. What’s Noteworthy – A 61-year-old twin toddler mom

◼︎ 7. What’s Popular – AI brings celebrities back from the dead

◼︎ 8. What’s Memorable – TikTok CEO hailed as “Asian hero”

◼︎ 9. Weibo Word of the Week – “Mellow People”

Dear Reader,

A devastating explosion in North China’s Yanjiao, claiming the lives of seven and injuring 27 others, has dominated Chinese social media discussions over the past few days. The incident not only raised questions about the cause of the blast but also sparked concerns about press freedom, as Chinese reporters were reportedly obstructed from their work at the scene. This fueled suspicions that local authorities might be withholding information from the public.

Despite its significant impact, the Yanjiao blast was not the most combustible topic on Chinese social media. Various other incidents and issues gained traction, largely driven by online nationalists.

The most eye-catching issue has been the so-called “battle of the two water bottles” (两瓶水之争), which emerged after the recent death of the much-beloved Chinese entrepreneur Zong Qinghou (宗庆后), founder of the Wahaha company known for its bottled water and beverages.

As detailed in our latest article here, a support campaign for the Wahaha brand morphed into a witch hunt against its major domestic competitor, Nongfu Spring. While Zong Qinghou was lauded as a patriotic entrepreneur, Nongfu Spring’s founder, billionaire Zhong Shanshan (钟睒睒), faced criticism for supposedly prioritizing profit over national interests.

From Weibo to Douyin and beyond, online influencers came up with all kinds of reasons why Nongfu Spring should be seen as an unpatriotic Chinese brand, from its product packaging containing Japanese elements to its water containing bugs.

One point of ongoing contention is the fact that Zhong’s son (his heir, Zhong Shuzi 钟墅子) holds American citizenship. This sparked anger among netizens who questioned Zhong’s allegiance to China. Numerous Douyin videos showed livestreamers pouring bottles of Nongfu Spring water down the drain, small shop owners recorded themselves removing Nongfu Spring products from store shelves, and overall sales plummeted. Because the issue was about affordable bottled water, participating in these kinds of ‘patriotic’ activities was relatively easy; consumer nationalism has never been cheaper.

When Chinese entrepreneur Li Guoqing (李国庆), co-founder of the e-commerce company Dangdang, defended Nongfu Spring and called for rationality, he too came under fire. Wasn’t his own son, Li Chengqing (李成青), an American citizen as well? Rumors about other Chinese entrepreneurs also started gaining traction.

While grassroots nationalist activities on Douyin and nationalist trends on Weibo aren’t new, the recent campaign against Nongfu Spring stands out as it targets a domestic company. Typically, Chinese online nationalism focuses on foreign brands, encouraging consumers to boycott foreign products and support domestic ones (buycott).

For instance, in 2021, Nike faced backlash and boycotts in China for its stance on Xinjiang cotton and a viral incident involving discrimination against a rural migrant worker by a Nike employee. The Chinese sportswear brand Erke indirectly profited from existing consumer sentiments over Nike, positioning itself as a patriotic alternative (read more here).

The current boycott of Nongfu Spring in favor of another ‘more patriotic’ Chinese brand represents a shift in online nationalism. It’s not top-down, it’s not state-led, and it’s not necessarily driven by political ideology. On the one hand, this is a sign of Chinese economic growth as domestic brands and companies are no longer considered the ‘underdog’ in a market dominated by bigger foreign brands. It reflects Chinese consumers’ confidence in made-in-China brands and a desire for them to embody their national identity.

On the other hand, this movement sheds light on the dynamics of contemporary Chinese social media and “the business of nationalism” (also described by Zhang & Ma, 2023, 899). Various actors in the Chinese digital ecosystem profit from the commodification of nationalist content on platforms like Weibo and Douyin, where patriotism and aggressive nationalism are amplified for commercial gain (Liao & Xia 2023, 1536).

Influencers, too, capitalize on patriotic narratives to garner attention, often at the expense of balanced discourse, as the algorithm pushes aggressively nationalist discourses to the forefront (Schneider 2022, 277).

Regular users of these platforms find themselves navigating an environment where extreme views dominate, perpetuating a cycle of nationalism. With a click, post, or video, they can be part of an online nationalist movement that’s driven by hype, not necessarily representative of nationalism on the ground, and sometimes more fleeting than a fast food trend — you could call it nationalist clicktivism.

All of this forms a toxic cocktail that can flare up and become explosive from time to time. But, this too shall pass. Some smart Chinese restaurant owners know that as well. They have started buying Nongfu Spring water in bulk. The price has never been lower, and the water will still be sellable by the time the storm has calmed. For them, too, nationalism has never been cheaper.

Best,

Manya (@manyapan)

References:

Liao, Sara and Grace Xia. 2023. “Consumer Nationalism in Digital Space: A Case-Study of the 2017 Anti-Lotte Boycott in China”. Convergence, 29(6), 1535-1554.

Schneider, Florian. 2022. “Emergent Nationalism in China’s Sociotechnical Networks: How Technological Affordance and Complexity Amplify Digital Nationalism.” Nations & Nationalism 28(1): 267-285.

Zhang, Chi and Yiben Ma. 2023. “Invented Borders: The Tension Between Grassroots Patriotism and State-Led Campaigns in China.” Journal of Contemporary China, 32(144), 897-913.

What’s Been Trending

1: Wahaha vs Nongfu Spring | It’s the big topic that’s been fermenting online for some time now: Nongfu and the online nationalists. The praise for one Chinese domestic water bottle brand, Wahaha, sparked online animosity toward the other, Nongfu Spring, after the death of Wahaha founder Zong Qinghou. While Wahaha is seen as a patriotic, proudly made-in-China brand, big competitor Nongfu Spring and its founder Zhong Shanshan are under attack for allegedly being profit-driven and disloyal to China. The online anti-Nongfu campaign has even led to people pouring out their Nongfu Spring water bottles. Read all about it here👇🏼

2: Party Slogan, Weibo Hashtag | A hashtag promoted by Party newspaper People’s Daily recently became top trending: “Wang Yi Says the Next China Will Still Be China” (#王毅说下一个中国还是中国#). The hashtag refers to statements made by China’s Foreign Minister, Wang Yi (王毅), during a press conference held alongside the Second Session of the 14th National People’s Congress. After Wang Yi’s remarks, the sentence ‘the next China will still be China’ has now solidified its place as a new catchphrase in the Communist Party jargon. But what does it actually mean?

3: Online Tributes to Toriyama | Chinese fans have been mourning the death of Japanese manga artist and character creator Akira Toriyama. On March 8, his production company confirmed that the 68-year-old artist passed away due to acute subdural hematoma. On Weibo, a hashtag related to his passing became trending as netizens shared their memories and appreciation for Toriyama’s work, as well as creating fan art in his honor (also see this tweet). Chinese readers form the largest fan community for Japanese comics and anime, and for many Chinese, the influential creations of Akira Toriyama, like “Dr. Slump” and particularly “Dragon Ball,” are cherished as part of their childhood or teenage memories.

What More to Know

◼︎ 🏛️ Boy Murdered by Classmates | A case in which a young boy from Feixiang county in Handan, Hebei, was murdered by three classmates has recently shocked the nation. The young boy, Wang Ziyao (王子耀), had suffered years of bullying before his three classmates, all 13 years old, brutally killed him. Wang had been missing for one day before his body was discovered buried in a greenhouse in a field nearby the home of one of the suspects. While the three suspects have now been detained, netizens and legal scholars are discussing whether the case could be handled by the Supreme People’s Procuratorate (SPP). Since an amendment to China’s Criminal Law in 2021, children between the ages of 12-14 can be held criminally responsible for extreme and cruel cases resulting in death or severe disability, if approved for prosecution by the SPP. A chilling video showing the palpable shock in Handan after Wang’s body was recovered by authorities also made its rounds online, see here. (Various related Weibo hashtags, including “#13-Year-Old Middle School Student Killed By Classmate, Three Arrested” #13岁初中生被同学杀害三人被刑拘#, 150 million views; “#CNR Discusses Case in Which Junior High School Student Was Killed and Buried by 3 Classmates #央广网评初中生被3名同学杀害掩埋#, 200 million views).

◼︎ ♪ U.S. TikTok Ban | Besides the battle over water, the battle over TikTok has also generated hashtags and discussions on Chinese social media after the US House of Representatives passed a bill that could lead to an American TikTok ban if parent company Bytedance does not sell the app. Security concerns surrounding TikTok’s ownership by a Chinese company and its access to American data have existed ever since the app became popular in the US, where it now has over 170 million users. Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin denounced the bill, suggesting it was unfair for US to cite security reasons to “arbitrarily” suppress TikTok. Many social media commenters agree with this stance, suggesting the app is solely targeted because of its Chinese parent company, unrelated to actual security risks. The Singaporean TikTok CEO Shou Zi Chew (周受资) is expected to pay US legislators a visit in the coming days to fight against the ban, which is something many netizens are looking forward to (Shou Zi Chew is very popular on Weibo). (Hashtag: “American House of Representatives Passes Tiktok Bill” #美众议院通过tiktok法案#, 160 million views; “#TikTok Strikes Back” #TikTok开始反击#, 140 million views).

◼︎ 🛒 Livestreaming Chaos | Many different topics popped up during this year’s 3.15 Consumer Day and the two-hour annual Chinese Consumer Day Gala television show, which is all about raising awareness of consumer rights. One hot topic within this context is China’s “chaos of live-streaming e-commerce” (直播带货乱象). People’s Daily reported that in 2023 alone, more than half (56.1%) of the complaints received at the “12315” consumer hotline were related to online shopping, primarily through livestreaming. Over the span of five years, complaints regarding live e-commerce have surged by 47 times. The primary concerns revolve around after-sales service problems, such as the difficulty in returning items, and quality issues, wherein products showcased in livestreams differ from what customers actually receive. (Hashtag “#Most After-Sales Complaints About Livestreaming Ecommerce” #售后服务直播带货投诉排名第一#, 34.8 million views).

◼︎ 🇬🇧 Where’s Kate? | Speculation and controversy surrounding the whereabouts of the Princess of Wales, Kate Middleton, have also surfaced on Weibo, where discussions about the UK royals have been trending in recent days. Worldwide, rumors about her condition emerged following her absence from any official public appearances since January 16, when she underwent abdominal surgery. The situation intensified when a photo of the Princess and her children, shared on Mother’s Day, raised suspicions of editing and photoshopping. Although Kate took responsibility for altering the image herself, the internet erupted with various theories about her situation, ranging from serious illness to marital issues or even another pregnancy. Some commenters suggest the Chinese interest in the issue is because “we love to watch palace drama.” (Hashtag “Where is Princess Kate?” #凯特王妃去哪了#, 40 million views; “Rumors of Princess Kate Missing Stirs Up UK” #凯特王妃失踪传闻搅动英国#, 43 million views).

◼︎ 🖋️ Chinese Author Mo Yan Under Attack | Another story that has been circulating online for some time involves Chinese blogger Wu Wanzheng (@说真话的毛星火) initiating a lawsuit against the renowned Chinese author and Nobel Prize winner Mo Yan (莫言). Wu accuses Mo Yan of distorting history and tarnishing the legacy of the Communist Party in his 1986 novel Red Sorghum (红高粱). The well-known Chinese internet commentator Hu Xijin recently came to Mo Yan’s defense, which actually increased media attention for the case. Although the initial attempt to sue Mo Yan was rejected by a Beijing court, Wu allegedly intends to persist with his mission. Opinions on the matter are divided: while some believe Wu is within his rights to pursue legal action against Mo Yan, others view the entire affair as a sensationalist grab for attention. Meanwhile, various articles and hashtags about the case have been taken offline (Weibo hashtag “Mo Yan Sued” #莫言被起诉#, 1.8 million views; “Hu Xijin: Person Suing Mo Yan Is Taking Words Out of Context” #胡锡进称起诉莫言者是在扣帽子断章取义#, 29 million clicks).

What’s the Drama

The Chinese historical drama “In Blossom” (花间令) currently ranks number one on Weibo. It premiered on the streaming platform Youku on March 15. The costume drama revolves around the story of the handsome Pan Yue (Liu Xueyi 刘学义), who marries Yang Caiwei (played by Ju Jingyi 鞠婧祎). She is murdered on the night of their wedding, and he is the prime suspect. But Yang Caiwei miraculously returns from the dead to uncover the truth.

▶️ This drama was directed by Zhong Qing (钟青), who is best known for directing suspenseful and romantic dramas.

▶️ The Weibo hashtag about “In Blossom” has received over two billion views already (#花间令#).

▶️ The first day after “In Blossom” was released, it already broke some viewing records; on March 16, 13.6% of Youku audiences had watched the drama, making it the first drama this year to become so popular within such a short timeframe.

You can watch In Blossom with English subtitles via YouTube here.

What Lies Behind

With emotions running high on social media, many are eager to learn about the fate awaiting the three young perpetrators in the trending case of the bullied boy from Handan, Hebei, who was killed and buried by his classmates. Online discussions mostly revolve around the legal and social aspects of this case.

There’s widespread frustration over the possibility of lenient punishment for the 13-year-old suspects due to their age. As China still has capital punishment, some people are even calling for execution once they turn 18.

These sentiments do not come out of the blue. In recent years, China has seen a rise in crimes, including murders, committed by minors. Many people are worried that without properly addressing the bullying problems that are prevalent among young people, the country will only see an increase in minors committing serious crimes like assault, rape and murder.

Online discussions show that people are reluctant to accept the “Law on the Protection of Minors” which recognizes the limited understanding young offenders may have of their own actions’ gravity and consequences. Chinese criminal psychologist and youth education expert Mei Jinli (李玫瑾) suggests that families or legal guardians should bear part of the responsibility exempted from the child due to their age.

Another issue that has caught people’s attention in this case is that all suspects and the victim are so-called “left-behind children” (留守儿童). With over 295 million Chinese rural migrant workers leaving their hometowns to find jobs in the city, many find themselves unable to bring their children due to the household registration system in China. Instead, they leave their children behind with grandparents or family.

Chinese experts and charities have been raising awareness of psychological trauma among these children – there are some 67 million of them – and are calling for changes in the household registration system so that migrant workers can bring their children with them instead of leaving them to fend for themselves.

The comments surrounding this case highlight how deeply it resonates with many. One commenter said he was a left-behind child himself, and when he saw the words “left-behind children” and “raised by grandparents” in the news, he couldn’t help but burst into tears.

What’s Noteworthy

During the Two Sessions, China’s annual parliamentary meetings, numerous proposals and “suggestions” (建议) put forth by National People’s Congress delegates became trending topics on Chinese social media. While a proposal in 2020 aimed to prohibit single women from freezing their eggs to encourage them to “marry and reproduce at the appropriate age,” a recent proposal suggests the opposite approach to address China’s declining birth rates: improving fertility treatment options for older Chinese women to facilitate childbearing for older parents.

Uncoincidentally, during the same week, a Chinese media outlet shared the story of a 61-year-old twin mom recounting her experience of ‘late parenthood.’ Having lost her 26-year-old son in a car accident in 2014, Zhang Yumei attempted to conceive for seven years and eventually welcomed healthy twin daughters in 2021, at the age of 58. In an interview with Chinese media, the senior citizen expressed that her two children have given her “the courage to continue living.” The story garnered significant attention on Chinese social media, with many sympathizing with Zhang Yumei. However, some netizens speculated whether authorities would now begin encouraging elderly women to use donated eggs for childbirth.

Read more about other proposals made during the Two Session in our article here.

What’s Popular

This video shows Chinese singer & actor Qiao Renliang (乔任梁) in 2024. He actually died in 2016.

Using AI tools, Chinese social media users are reviving deceased celebrities like Qiao, Coco Lee, or Godfrey Gao. By using old videos and images, artificial intelligence digitally recreates them, bringing them back to life in online videos. A recent example sparking controversy is the video featuring Chinese singer and actor Kimi Qiao Renliang (乔任梁), who took his own life in 2016 at the age of 28. In the AI-generated video, Qiao states, “Actually, I never really left…”

His parents are unsettled by the video. Qiao’s father is now urging netizens to delete these videos of his son. He says they were created without permission and violate his son’s portrait rights. It has sparked some much-needed discussion on the legal and ethical issues surrounding so-called ‘AI resurrection’ (AI复活).

In an online poll conducted by Sina Hotspot (新浪热点) among 80,000 netizens on Weibo, a significant majority of respondents, over 66,000, expressed that recreating deceased celebrities is unacceptable. Only 2,100 people said they see practice as a nice way to remember celebrities who’ve passed.

What’s Memorable

This pick from our archive takes us back to when Shou Zi Chew (周受资, Zhou Shouzi), the Singaporean CEO of TikTok, appeared before the House Energy and Commerce Committee in the United States, facing a four-and-a-half-hour hearing over data security and harmful content on the TikTok app. Some bloggers and commenters noted how Chew fits the supposed idea of a ‘perfect Asian’ by staying calm despite unreasonable allegations and emphasizing business interests over culture. The so-called “Mr. Perfect In the Eye of the Storm” is going back to defend TikTok this week, so we can expect him to receive a lot of support from Chinese netizens again. Read more about it here 👇

Weibo Word of the Week

“Mellow People” | Our Weibo Word of the Week is “Mellow People” or “Mellow Person” (dàn rén 淡人), a term that’s popped up recently to self-describe the mental state of young people in China today.

The word dàn 淡, which I’ve translated as ‘mellow’ in this context, can mean numerous things in China: it’s light, calm, indifferent, pale, or even trivial. Being a dàn individual, a dànrén 淡人, has recently come to be used by young people to describe themselves and how they experience life. They might want to quit their crappy job, but it generates money so it’s okay. They have to commute for hours every day, but the rent is cheaper so it’s okay. They are being forced to go on blind dates by their parents and actually don’t want to, but they don’t have the energy to refuse so it’s okay.

Being this ‘mellow’ or ‘unperturbed’ means being indifferent in a calm and light way. Not unlike previous Chinese popular expressions such as “lying flat” (躺平) and being “Buddha-like” (佛系) (read here), it’s a way to cope with the challenges and pressures faced by Chinese young people today, but it’s a bit more positive than being completely passive (lying flat): it’s a passive acceptance of life as it is, embracing dull daily routines or competitive work environments without resistance. The art of being or becoming a dàn rén is also referred to as 淡人学 dànrén xué, which could be translated as ‘Mellowism’ or, perhaps even better, ‘Unperturbabilism.’

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

You may like

China ACG Culture

“Black Myth: Wukong”: From Gaming Screens to the CMG Spring Festival Gala?

Published

2 days agoon

January 21, 2025

FROM THE WEIBO WATCH PREMIUM NEWSLETTER

Is Chinese game sensation ‘Black Myth Wukong’ making a jump from gaming screens to the CMG Spring Festival Gala? There’s already some online excitement over a potential performance at the biggest liveshow of the year.

The countdown to the most-watched show of the year has begun. On January 29, the Year of the Snake will be celebrated across China, and as always, the CMG Spring Festival Gala, broadcast on CCTV1, will air on the night leading up to midnight on January 28.

Rehearsals for the show began last week, sparking rumors and discussions about the must-watch performances this year. Soon, the hashtag “Black Myth: Wukong – From New Year’s Gala to Spring Festival Gala” (#黑神话悟空从跨晚到春晚#) became a topic of discussion on Weibo, following rumors that the Gala will feature a performance based on the hugely popular game Black Myth: Wukong.

Three weeks ago, a 16-minute-long Black Myth: Wukong performance already was a major highlight of Bilibili’s 2024 New Year’s Gala (B站跨年晚会). The show featured stunning visuals from the game, anime-inspired elements, special effects, spectacular stage design, and live song-and-dance performances. It was such a hit that many viewers said it brought them to tears. You can watch that show on YouTube here.

While it’s unlikely that the entire 16-minute performance will be included in the Spring Festival Gala (it’s a long 4-hour show but maintains a very fast pace), it seems highly possible that a highlight segment of the performance could make its way to the show.

Recently, Black Myth: Wukong was crowned 2024’s Game of the Year at the Steam Awards. The game is nothing short of a sensation. Officially released on August 20, 2024, it topped the international gaming platform Steam’s “Most Played” list within hours of its launch. Developed by Game Science, a studio founded by former Tencent employees, Black Myth: Wukong draws inspiration from the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West. This legendary tale of heroes and demons follows the supernatural monkey Sun Wukong as he accompanies the Tang Dynasty monk Xuanzang on a pilgrimage to India to retrieve Buddhist scriptures. The game, however, focuses on Sun Wukong’s story after this iconic journey.

The success of Black Myth: Wukong cannot be overstated—I’ve also not seen a Chinese video game be this hugely popular on social media over the past decade. Beyond being a blockbuster game it is now widely regarded as an impactful Chinese pop cultural export that showcases Chinese culture, history, and traditions. Its massive success has made anything associated with it go viral—for example, a merchandise collaboration with Luckin Coffee sold out instantly.

If Black Myth: Wukong does indeed become part of the Spring Festival Gala, it will likely be one of the most talked-about and celebrated segments of the show. If it does not come on, which we would be a shame, we can still see a Black Myth performance at the pre-recorded Fujian Spring Festival Gala, which will air on January 29.

Lastly, if you’re not into video games and not that interested in watching the show, I still highly recommend that you check out the game’s music. You can find it on Spotify (link to album). It will also give you a sense of the unique beauty of Black Myth: Wukong that you might appreciate—I certainly do.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Digital

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

As American ‘TikTok Refugees’ flock to China’s Xiaohongshu (Rednote), their encounter with ‘Li Hua’ strikes a chord in divided times.

Published

3 days agoon

January 20, 2025

FROM THE WEIBO WATCH PREMIUM NEWSLETTER

China’s Xiaohongshu (Rednote) has seen an unprecedented influx of foreign “TikTok refugees” over the past week, giving rise to endless jokes. But behind this unexpected online migration lie some deeper themes—geopolitical tensions, a desire for cultural exchange, and the unexpected role of the fictional character Li Hua in bridging the divide.

Imagine you are Li Hua (李华), a Chinese senior high school student. You have a foreign friend, far away, in America. His name is John, and he has asked you for some insight into Chinese Spring Festival, for an upcoming essay has to write for the school newspaper. You need to write a reply to John, in which you explain more about the history of China’s New Year festival and the traditions surrounding its celebrations.

This is the kind of writing assignment many Chinese students have once encountered during their English writing exams in school during the Gaokao (高考), China’s National College Entrance Exams. The figure of ‘Li Hua’ has popped up on and off during these exams since at least 1995, when Li invited foreign friend ‘Peter’ to a picnic at Renmin Park.

Over the years, Li Hua has become somewhat of a cultural icon. A few months ago, Shangguan News (上观新闻) humorously speculated about his age, estimating that, since one exam mentioned his birth year as 1977, he should now be 47 years old—still a high school student, still helping foreign friends, and still introducing them to life in China.

Li Hua: the connector, the helper, the icon.

This week, however, Li Hua unexpectedly became a trending topic on social media—in a week that was already full of surprises.

With a TikTok ban looming in the US (delayed after briefly taking effect on Sunday), millions of American TikTok users began migrating to other platforms this month. The most notable one was the Chinese social media app Xiaohongshu (now also known as Rednote), which saw a massive influx of so-called “TikTok refugees” (Tiktok难民). The surge propelled Xiaohongshu to the #1 spot in app stores across the US and beyond.

This influx of some three million foreigners marked an unprecedented moment for a domestic Chinese app, and Xiaohongshu’s sudden international popularity has brought both challenges and beautiful moments. Beyond the geopolitical tension between the US and China, Chinese and American internet users spontaneously found common ground, creating unique connections and finding new friends.

While the TikTok/Xiaohongshu “honeymoon” may seem like just a humorous trend, it also reflects deeper, more complex themes.

✳️ National Security Threat or Anti-Chinese Witchhunt?

At its core, the “TikTok refugee” trend has sprung from geopolitical tensions, rivalry, and mutual distrust between the US and China.

TikTok is a wildly popular AI-powered short video app by Chinese company ByteDance, which also runs Douyin, the Chinese counterpart of the international TikTok app. TikTok has over 170 million users in the US alone.

A potential TikTok ban was first proposed in 2020, amid escalating US-China tensions. President Trump initiated the move, citing security and data concerns. In 2024, the debate resurfaced in global headlines when President Biden signed the “Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act,” giving ByteDance nine months to divest TikTok or face a US ban.

TikTok, however, has continuously insisted it is apolitical, does not accept political promotion, and has no political agenda. Its Singaporean CEO Shou Zi Chew maintains that ByteDance is a private business and “not an agent of China or any other country.”

🇺🇸 From Washington’s perspective, TikTok is viewed as a national and personal security threat. Officials fear the app could be used to spread propaganda or misinformation on behalf of the Chinese Communist Party.

🇨🇳 Beijing, meanwhile, criticizes the ban as an act of “bullying,” accusing the US of protectionism and attempting to undermine China’s most successful internet companies. They argue that the ban reflects America’s inability to compete with the success of Chinese digital products, labeling the scrutiny around TikTok as a “witch hunt.”

Political cartoon about the American “witchhunt” against TikTok, shared on Weibo in 2023, also published on Twitter by Lianhe Zaobao.

“This will eventually backfire on the US itself,” China’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin predicted in 2024.

Wang turned out to be quite right, in a way.

When it became clear in mid-January that the ban was likely to become a reality, American TikTok users grew increasingly frustrated and angry with their government. For many of these TikTok creators, the platform is not just a form of entertainment—it has become an essential part of their income. Some directly monetize their content through TikTok, while others use it to promote services or products, targeting audiences that other platforms like Facebook, Instagram, or X can no longer reach as effectively.

Initially, the mass migration of American users to Xiaohongshu was a symbolic protest against US policies. Users advocated for the right to choose their preferred social media, and voiced their frustration at how their favorite app had become a pawn in US-China geopolitical tensions. Rejecting the narrative that “data must be protected from the Chinese,” many pointed out that privacy concerns were equally valid for US-based platforms. As an act of playful political defiance, these users downloaded Xiaohongshu to demonstrate they didn’t fear the government’s warnings about Chinese data collection.

(If they had the option, by the way, they would have installed Douyin—the actual Chinese version of TikTok—but it is only available in Chinese app stores, whereas Xiaohongshu is accessible in international stores, so it was picked as ‘China’s version of TikTok.’)

Xiaohongshu is actually not the same as TikTok at all. Founded in 2013, Xiaohongshu (literal translation: Little Red Book) is a popular app with over 300 million users that combines lifestyle, travel, fashion, and cosmetics with e-commerce, user-generated content, and product reviews. Like TikTok, it offers personalized content recommendations and scrolling videos, but is otherwise different in types of engagement and being more text-based.

As a Chinese app primarily designed for a domestic audience, the sudden wave of foreign users caused significant disruption. Xiaohongshu must adhere to the guidelines of China’s Cyberspace Administration, which requires tight control over information flows. The unexpected influx of foreign users undoubtedly created challenges for the company, not only prompting them to implement translation tools but also recruiting English-speaking content moderators to manage the new streams of content. Foreigners addressing sensitive political issues soon found their accounts banned.

Of course, there is undeniable irony in Americans protesting government control by flocking to a Chinese app functioning within an internet system that is highly controlled by the government—a move that sparked quite some debate and criticism as well.

✳️ The Sino-American ‘Dear Li Hua’ Moment

While the initial hype around Xiaohongshu among TikTok users was political, the trend quickly shifted into a moment of cultural exchange. As American creators introduced themselves on the platform, Chinese users gave them a warm welcome, eager to practice their English and teach these foreign newcomers how to navigate the app.

Soon, discussions about language, culture, and societal differences between China and the US began to flourish. Before long, “TikTok refugees” and “Xiaohongshu natives” were collaborating on homework assignments, swapping recipes, and bonding through humor.

For instance, Chinese users jokingly asked the “TikTok refugees” to pay a “cat tax” for seeking refuge on their platform, which American users happily fulfilled by posting adorable cat photos. American users, in turn, joked about becoming best friends with their “Chinese spies,” playfully mocking their own government’s fears about Chinese data collection.

The newfound camaraderie sparked creativity, as users began generating humorous images celebrating the bond between American and Chinese netizens—like Ronald McDonald cooking with the Monkey King or the Terra Cotta Soldier embracing the Statue of Liberty. Later, some images even depicted the pair welcoming their first “baby.”

🇺🇸 At the same time, it became clear just how little Americans and Chinese truly know about each other. Many American users expressed surprise at the China they discovered through Xiaohongshu, which contrasted sharply with negative portrayals they’ve seen in the media. While some popular US narratives often paint Chinese citizens as “brainwashed” by their government, many TikTok users began to reflect on how their own perspectives had been shaped—or even “manipulated”—by their media and government.

🇨🇳 For Chinese users, the sudden interaction underscored their digital isolation. Over the past 15 years, China has developed its own tightly regulated digital ecosystem, with Western platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube inaccessible in the mainland. While this system offers political and economic advantages, it has left many young Chinese people culturally hungry for direct interaction with foreigners—especially after years of reduced exchange caused by the pandemic, trade tensions, and bilateral estrangement. (Today, only some 1,100 American students are reportedly studying in China.)

The enthusiasm and eagerness displayed by American and Chinese Xiaohongshu users this week actually underscores the vacuum in cultural exchange between the two nations.

As a result of the Xiaohongshu migration, language-learning platform Duolingo reported a 216% rise in new US users learning Mandarin—a clear sign of growing interest in bridging the US-China divide.

Mourning the lack of intercultural communication and celebrating this unexpected moment of connection, Xiaohongshu users began jokingly asking Americans if they had ever received their “Li Hua letters.”

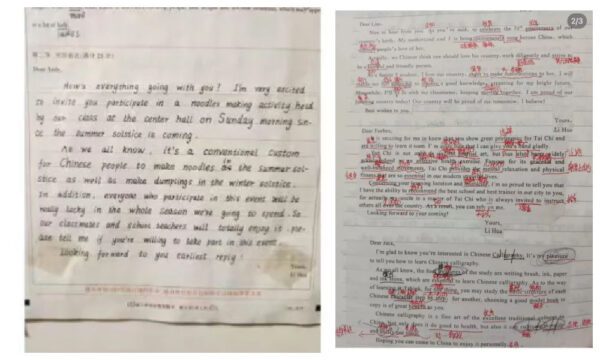

What started as some lighthearted remarks evolved into something much bigger as Chinese users dug up their old Gaokao exam papers and shared the letters they had written to their imaginary foreign friends years ago. These letters, often carefully stored in drawers or organizers, were posted with captions like, “Why didn’t you reply?” suggesting that Chinese students had been trying to reach out for years.

Example letters on Xiaohongshu: ‘Li Hua’ writing to foreign friends.

The story of ‘Li Hua’ and the replies he never received struck a chord with American Tiktok users. One user, Debrah.71, commented:

“It was the opposite for us in the USA. When I was in grade school, we did the same thing—we had foreign pen pals. But they did respond to our letters.”

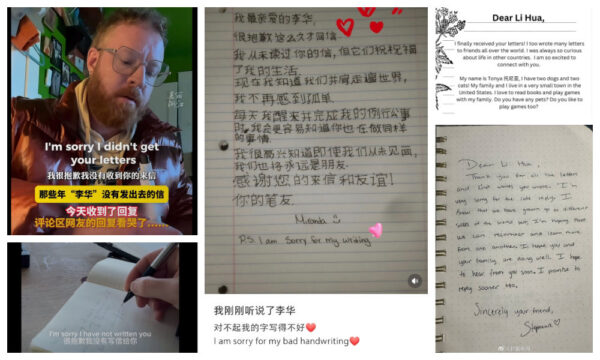

Then, something extraordinary happened: Americans started replying to Li Hua.

One user, Douglas (@neonhotel), posted a heartfelt video of him writing a letter to Li Hua:

📝”Dear Li Hua, I’m sorry I didn’t get your letters. I understand you’ve been writing me for a long time, but now I’m here to reply. Hello, from your American friend. I hope you’re well. Life here is pretty normal—we go to work, hit the gym, eat dinner, watch TV. What about you? Please write back. I’m sorry I didn’t reply before, but I’m here now. Your friend, Douglas.”

Another user, Tess (@TessSaidThat), wrote:

📝”Dear Li Hua, I hope this letter finds you well. I’m so sorry my response is so late. My government never delivered your letters. Instead, they told me you didn’t want to be my friend. Now I know the truth, and I can’t wait to visit. Which city should I visit first? With love, Tess.”

Examples of Dear Li Hua letters.

Other replies echoed similar sentiments:

📝”Dear Li Hua, I’m sorry the world kept us apart.”

📝”I know we don’t speak the same language, but I understand you clearly. Your warmth and genuine kindness transcend every barrier.”

📝”Did you achieve your dreams? Are you still practicing English? We’re older now, but wherever we are, happiness is what matters most.”

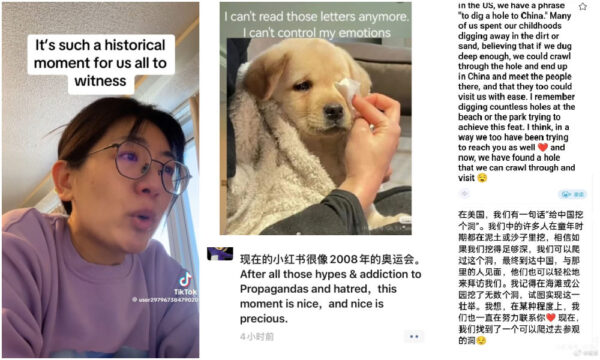

These exchanges left hundreds of users—both Chinese and American, young and old, male and female—teary-eyed. In a way, it’s the emotional weight of the distance—represented by millions of unanswered letters—that resonated deeply with both “TikTok refugees” and “Xiaohongshu natives.”

Emotional responses to the Li Hua letters.

The letters seemed to symbolize the gap that has long separated Chinese and American people, and the replies highlighted the unusual circumstances that brought these two online communities together. This moment of genuine cultural exchange made many realize how anti-Chinese, anti-American sentiments have dominated narratives for years, fostering misunderstandings.

Xiaohongshu commenter.

On the Chinese side, many people expressed how emotional it was to see Li Hua’s letters finally receiving replies. Writing these letters had been a collective experience for generations of Chinese students, creating messages to imaginary foreign friends they never expected to meet.

Receiving a reply wasn’t just about connection; it was about being truly seen at a time when Chinese people often feel underrepresented or mischaracterized in global contexts. Some users even called the replies to the Li Hua letters a “historical moment.”

✳️ Unity in a Time of Digital Divide

Alongside its political and cultural dimensions, the TikTok/Xiaohongshu “honeymoon” also reveals much about China and its digital environment. The fact that TikTok, a product of a Chinese company, has had such a profound impact on the American online landscape—and that American users are now flocking to another Chinese app—showcases the strength of Chinese digital products and the growing “de-westernization” of social media.

Of course, in Chinese official media discourse, this aspect of the story has been positively highlighted. Chinese state media portrays the migration of US TikTok users to Xiaohongshu as a victory for China: not only does it emphasize China’s role as a digital superpower and supposed geopolitical “connector” amidst US-China tensions, but it also serves as a way of mocking US authorities for the “witch hunt” against TikTok, suggesting that their actions have ultimately backfired—a win-win for China.

The Chinese Communist Party’s Publicity Department even made a tongue-in-cheek remark about Xiaohongshu’s sudden popularity among foreign users. The Weibo account of the propaganda app Study Xi, Strong Country, dedicated to promote Party history and Xi Jinping’s work, playfully suggested that if Americans are using a Chinese social media app today, they might be studying Xi Jinping Thought tomorrow, writing: “We warmly invite all friends, foreign and Chinese, new and old, to download the ‘Big Red Book’ app so we can study and make progress together!”

Perhaps the most positive takeaway from the TikTok/Xiaohongshu trend—regardless of how many American users remain on the app now that the TikTok ban has been delayed—is that it demonstrates the power of digital platforms to create new, transnational communities. It’s unfortunate that censorship, a TikTok ban, and the fragmentation of global social media triggered this moment, but it has opened a rare opportunity to build bridges across countries and platforms.

The “Dear Li Hua” letters are not just personal exchanges; they are part of a larger movement where digital tools are reshaping how people form relationships and challenge preconceived notions of others outside geopolitical contexts. Most importantly, it has shown Chinese and American social media users how confined they’ve been to their own bubbles, isolated on their own islands. An AI-powered social media app in the digital era became the unexpected medium for them to share kind words, have a laugh, exchange letters, and see each other for what they truly are: just humans.

As millions of Americans flock back to TikTok today, things will not be the same as before. They now know they have a friend in China called Li Hua.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

What’s on Weibo Chapters

Subscribe

“Black Myth: Wukong”: From Gaming Screens to the CMG Spring Festival Gala?

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

TikTok Refugees, Xiaohongshu, and the Letters from Li Hua

15 Years of Weibo: The Evolution of China’s Social Media Giant

Introducing What’s on Weibo Chapters

The Price of Writing Smut: Inside China’s Crackdown on Erotic Fiction

Controversial Wanghong Livestreamers Are Becoming a Weibo Staple in China

Weibo Watch: “Comrade Trump Returns to the Palace”

The ‘Cycling to Kaifeng’ Trend: How It Started, How It’s Going

Hu Xijin’s Comeback to Weibo

Our Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

The Viral Bao’an: How a Xiaoxitian Security Guard Became Famous Over a Pay Raise

Why Chinese Hit Movie “Her Story” is ‘Good Stuff’: Stirring Controversy and Celebrating Female Perspectives

Chiung Yao’s Suicide Farewell Letter: An English Translation

12-Year-Old Girl from Shandong Gets Infected with HPV: Viral Case Exposes Failures in Protecting Minors

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music10 months ago

China Music10 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Insight11 months ago

China Insight11 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Digital8 months ago

China Digital8 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI