Featured

Weibo Watch: Frogs in Wells

Taiwan elections discussions remained relatively muted on Weibo, with limited hashtags and controlled narratives. Read more about what’s trending, from Harbin to Xinjiang, in this 22nd edition of Weibo Watch.

Published

1 year agoon

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #22

This week’s newsletter:

◼︎ 1. Editor’s Note – Frogs in wells

◼︎ 2. What’s Been Trending – A closer look at the featured stories

◼︎ 3. What More to Know – Five bit-sized trends

◼︎ 4. What’s the Drama – Top TV to watch

◼︎ 5. What Lies Behind – Xinjiang as copy cat

◼︎ 6. What’s Noteworthy – Balloons up in the air

◼︎ 7. What’s Popular – Jia Ling’s back in the spotlight

◼︎ 8. What’s Memorable – Gu, the controversial snow princess

◼︎ 9. Weibo Word of the Week – “Southern Little Potatoes”

Dear Reader,

While the Taiwan elections have been making headlines in international media for the past two weeks, discussions about the topic haven’t been as buzzing on Chinese social media.

As voters across Taiwan headed to the polls to elect a new president, the world watched closely as the three-way race between Kuomintang’s Hou Yu-ih, Taiwan People’s Party’s Ko Wen-je, and Lai Ching-te of the Democratic Progressive Party unfolded. Meanwhile, Weibo’s trending topic lists were predominantly filled with entertainment and travel news.

In the hours following the news that Lai Ching-te (赖清德) was elected to be Taiwan’s president, you could almost hear the crickets on the social media platform, where the only news accounts posting about the election’s outcome on Saturday evening were the Russian state-owned Ruptly and RT. Hashtags that had been active earlier in the day suddenly disappeared during the night, including the “Taiwan elections” (#台湾选举#) hashtag, and new ones like “Lai Ching-te wins the 2024 Taiwan regional leadership election” (#赖清德赢得2024年台湾地区领导人选举#).

Since the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) came to power in 2016, Chinese official media have described the ruling party as collaborating with “external forces” to seek independence and pursuing policies hostile to the mainland. Lai Ching-te, also known as William Lai, has stated that he is determined to safeguard Taiwan from threats and intimidation from Beijing and to maintain the cross-strait status quo.

“We can only wait for the mainland media to announce the results,” one prominent Taiwan-focused blogging account remarked on Saturday night, awaiting Chinese state media to come up with the ‘correct’ headlines and hashtags needed to facilitate further discussions on the platform.

By 22:45 Beijing time, about three hours after the election results made international headlines, Chinese official media channels such as Xinhua and Global Times finally reported about Lai’s win, citing spokesperson Chen Binhua of the Taiwan Affairs Office. He stated that the DPP win does not represent the Taiwanese mainstream; that Taiwan is a part of China; and that the island’s future reunification with the motherland will not be affected. Comment sections were switched off.

Some bloggers wondered why Weibo had seemingly blocked the election results from the hot search lists and why the topic was so controlled. After all, they said, isn’t this just about “the new governor of Taiwan province”? Some commenters jumped on other popular hashtags, mainly related to the super popular ‘Weibo Night’ event, to express views on the elections or how underreported they were. Weibo commenters also used phrases such as “poison frogs,” “Tai[wan] frogs,” or “the frog village has elected its new chief” to discuss the election results.

On Chinese social media, people from Taiwan are often referred to as frogs, inevitably leading to other frog-related phrases to talk about the island. The ‘Taiwan frog’ meme, which has become especially widespread during Tsai’s rule, is a reference to the well-known fable by philosopher Zhuangzi about a frog in a well who does not believe it when a turtle tells him that the world is bigger than the view from the well. The frog stubbornly denies the existence of the wider world and asserts that nothing lies beyond what he can see. The idiom ‘frog in the well’ (井底之蛙 jǐngdǐzhīwā) thus refers to people who are narrow-minded and who have a limited outlook on their life and surroundings.

The frog meme is used to describe Taiwanese who are thought to be confined to their island’s perspective and unable to see beyond it. It’s a play on words, as Tai-wan 台湾 and Tai-wa 台蛙 (= Tai-frog) sound similar. Mainlanders started calling Taiwanese ‘little frogs’ (蛙蛙) when they encountered Taiwanese commentators talking about the mainland as if it were underdeveloped and backward, seemingly unaware of China’s rapid progress over the past decades. A notable example is a Taiwanese TV host who, years ago, claimed that people in China couldn’t even afford boiled tea eggs and packaged pickled vegetables, sparking many jokes on Chinese social media.

Of course, there is some irony in Chinese netizens referring to Taiwanese as if they’re stuck in a well when Chinese narratives about Taiwan are so controlled and are mostly focused on cross-strait relations alone. On Sunday morning, the election result finally showed up in Weibo’s top trending lists with the hashtag “Taiwan is part of China, this basic fact won’t change” (#台湾是中国一部分的基本事实不会改变#). The hashtag had received over 260 million views by afternoon. Its main post by CCTV accumulated over 6329 replies. However, only 17 of them were visible, each and every single one reaffirming: “There is only one China.”

In this social media age, both in China and globally, it’s all too easy to find ourselves in echo chambers and filter bubbles, where we’re exposed only to voices that echo our existing beliefs — aren’t we all ‘frogs in the well’ at some point? Observing discussions about Taiwan on Western social media platforms, most commenters tend to narrow their focus to the elections, framing them as purely geopolitical. This perspective can create the impression that Taiwanese voters only express views that can be labeled as ‘pro-US,’ ‘anti-mainland,’ or ‘pro-China.’

“It’s not war with China that Taiwan’s young voters worry about, it’s jobs, housing, wages,” BBC’s Tessa Wong posted on X, where political scientist Sheena Chestnut Greitens added: “Important reminder: outside observers view Taiwan’s election primarily through the lens of geopolitical tensions and the threat of conflict, but many Taiwan voters also prioritize more bread-and-butter issues.”

Not everything is about great power struggles; not everything is about China vs the US; and not everything is a competition. This reminds me of something else I’d like to briefly share with you here. When The Guardian reached out to me a few weeks ago and asked if there was a topic I found particularly noteworthy in 2023 when it comes to China’s online environment, I immediately knew I wanted to write about the exploding popularity of ChatGPT, which also became a major topic of discussion across Chinese social media channels at that time: why was ChatGPT not “made in China”? You can read my debut piece for The Guardian, “In the Race for AI Supremacy, China and the US Are Traveling on Entirely Different Tracks,” through this link here.

Miranda Barnes and Ruixin Zhang contributed to this Weibo Watch newsletter, which I hope you find useful.

Best,

Manya

(PS You can also find me on Instagram and Threads nowadays but I’m still most active on X here.)

What’s Been Trending

1: A Snowball Effect | Harbin has been trending every 👏 single 👏 day 👏 on Chinese social media over the past two weeks. The hype surrounding the city and its Snow and Ice Festival is similar to the buzz surrounding Shandong’s Zibo in 2023, and it shows that Chinese tourism boards are seriously stepping up their game in the post-Covid travel era. But although the Harbin hype is the result of a well-coordinated marketing campaign that has been in the making for a year, there is also that special something, the organic buzz, that has snowballed the city’s success this season ✨ . Read all about it here 👇🏼

2: Show-Inspired Journeys | The Chinese TV series Meet Yourself has significantly boosted the popularity of Dali in Yunnan. The series’ success, coupled with the official funding behind it, not only underscores the impactful role of Chinese television dramas in tourism but also illustrates how Chinese travel destination promotional strategies are being reshaped in a competitive post-Covid era.

3: From Avant-Garde Writer to Scruffy Pup | On Chinese social media, Yu Hua has transcended his status as one of China’s most renowned contemporary writers. Surrounded by memes, online jokes, and fans born after 2000, he has emerged as a cultural icon for China’s younger generations. His rise as an online celebrity highlights that Chinese youth value relatability and likability over literary prestige.

What More to Know

Besides the bigger international news topics such as the Taiwan elections, Japan earthquake, Middle East crisis, or the Epstein list, these bite-sized topics also went trending on Chinese social media 👇

◼︎ 🌟 Weibo Night | As every year, Weibo Night, unsurprisingly, managed to become the no 1 entertainment topic of the week. It is the much-anticipated live-broadcasted ceremony that looks back on Sina Weibo’s hottest celebrities, entertainment productions, and happenings of the past year. Hosted by the Sina media company, the night has been a recurring event since 2003 – long before the Sina Weibo platform was launched. The night was initially known as the ‘Sina Grand Ceremony’ (新浪网络盛典) until it turned into the ‘Weibo Night’ (微博之夜) in 2010. This year’s edition took place on January 13 – check in on What’s on Weibo later for the highlights. For last year’s list of winners, check here. (Weibo Hashtag “Weibo Night” ##微博之夜##, billions of views, 970 million views on Friday alone and a staggering 7.6 billion views on Saturday!).

◼︎ 🍎 Homeless Chinese PhD graduate in NYC | The story of a Chinese academic who turned from a “genius student” in physics at Fudan University to a homeless man in the US has gone viral recently. The man named Sun (孙) first attracted attention due a Chinese vlogger spotting him sleeping on the streets in New York. After graduating, doing his PhD in the US and obtaining a green card, the man dealt with mental issues and started wandering the streets for 16 years. With help coming from all directions, the 54-year-old Sun is now off the streets and will possibly get help in returning to his family in China (Weibo hashtag “Homeless Fudan Doctor Gets In Touch with Hometown” ##复旦流浪博士已与家乡取得联系##, 180 million views; “Family Members Already Know Fudan Doctor Who Stayed in US Is Wandering NY Streets” #家属已知复旦留美博士流浪纽约街头#, 290 million views).

◼︎ 💍 One-third of 30-Something Urbanites Are Single | Some remarkable social trends found in China’s 2023 Population and Employment Statistics Yearbook (中国人口和就业统计年鉴2023) have recently triggered online discussions. According to the statistics, the unmarried rate among the 30-year-old population in China’s urban areas now exceeds 30%. Experts explain that this is mostly related to Chinese younger generations postponing marriage due to spending longer time in education and also because of the relatively high cost of living. At the same time, China’s rural areas have also seen a staggering decrease in marriage rates (in 25-29 age group over 47% is unmarried), which can mostly be explained due to a gender imbalance in marriageable age groups. (Weibo hashtags “30% of 30-Somethings in Chinese Cities are Single” #全国城市30岁人群未婚率超30%#, 27+ million views; “Late Marriage Trend Has Spread from Cities to Villages” #晚婚已从城市蔓延到农村#, hashtag page taken offline).

◼︎ 🍣 Fukushima Food Poisoning | Lots of Japan news went trending on Chinese social media this month, from the devastating earthquake along Japan’s western coast to the Japan Airlines jet collision. Smaller Japan news that went trending this week is a collective food poisoning incident that took place in Fukushima earlier this month. Among many guests who stayed and dined at a local Fukushima hotel, 101 people fell ill after eating raw fish. Last year, Japan also saw several other large-scale food poisoning incidents. This Fukushima incident especially went trending on Chinese social media within the context of the release of treated radioactive water from the ruined Fukushima nuclear plant, which became one of the biggest social media topics in 2023. Although unrelated, netizens link the food poisoning incident to the dangers of radioactive water (Weibo hashtag “100 people in Japan’s Fukushima Get Food Poisoning from Eating Raw Fish” ##日本福岛百人因吃生鱼片食物中毒##, 160 million views).

◼︎ 🐼 Yaya’s Weight Gain | Panda Yaya became one of the most discussed pandas of 2023. This female panda resided in the Memphis Zoo in the United States for most of her life and attracted significant attention on Chinese social media platforms after netizens expressed concern about her seemingly thin and unhealthy appearance. When the beloved panda finally returned to Beijing after two decades, her arrival became a true social media spectacle. Now, living in the Beijing Zoo, Yaya is often spotted enjoying her bamboo dinners and she clearly gained a lot of weight, much to the delight of netizens who see this as a sign that the panda is doing much better in China than in the US. (Weibo hashtag “Yaya Became A-Letter Chubby Panda”” ##丫丫胖成了A字熊##, 120 million views).

What’s the Drama

We’re introducing this new short Weibo Watch segment to keep you in the loop about some of the most-discussed TV dramas and series in China, as they’re a significant part of China’s online environment. While the South Korean TV drama Death’s Game (#死期将至#), of which Part 2 was released on Jan 5, has been popular on Chinese social media recently, it’s Wong Kar-wai’s Blossoms Shanghai (繁花) that is among the top trending Chinese TV dramas at the moment. The series first started airing on CCTV-8 and Tencent Video on December 27.

Adapted from Jin Yucheng’s award-winning novel, Blossoms Shanghai is set in 1990s Shanghai and tells the story of the young man A Bao (played by the ‘Weibo King’ Hu Ge 胡歌) who aims to become a successful businessman and self-made millionaire during China’s booming economic reform period. The series portrays a sharp contrast between the man’s troubled past and the city’s vibrant present. Noteworthy:

▶️ This is the first TV drama produced by Hong Kong film director Wong Kar-Wai, internationally acclaimed for movies such as Chungking Express and In the Mood for Love.

▶️ Particularly noteworthy is the inclusion of the now 91-year-old renowned Chinese actor You Benchang (游本昌), famous for his iconic role as the legendary monk Ji Gong in the 1980s. Despite his age, the actor spent entire days on set with his much younger colleagues, enduring ten-hour working days.

▶️ Due to the success of the series, locations featured in it are experiencing an influx of visitors, especially Shanghai’s Huanghe Road (黄河路). Shanghai’s Fairmont Peace Hotel on Nanjing East Road, also featured in Blossoms Shanghai, has even introduced a new menu featuring various dishes that also come up in the series.

An international/subtitled online release is expected soon, but if you’re in China, you can watch via Tencent here.

What Lies Behind

Similar to Zibo in 2023, it’s the city of Harbin that has successfully generated a significant social media buzz this season, attracting hordes of winter tourists. On the other side of Northern China, Xinjiang Province is also eager to step into the spotlight.

While the Harbin International Ice and Snow Festival celebrated its official opening ceremony on January 5th, Xinjiang’s Ili Prefecture hosted an event to promote its first Tianma Ice and Snow Tourism Festival. The Snow Festival, scheduled to open on January 14th at Zhaosu County’s Wetland Park, will feature various winter activities and ice & snow sculpture exhibitions. By incorporating folk culture elements and highlighting its numerous ski resorts, local authorities aim to position Xinjiang as the third trending tourist destination after Zibo and Harbin.

However, the ‘online buzz’ surrounding Xinjiang hasn’t unfolded exactly as they had hoped. Local Xinjiang residents began expressing their opinions on social media, including on promotional videos on Douyin, cautioning tourists about high prices. For example, they pointed out that their popular spicy fried chicken dish (辣子鸡) could cost over 200 RMB (US$28), more than double the price elsewhere in China. A well-known Xinjiang vlogger suggested that budget-conscious tourists might find visiting the region in the summer more economical, while others criticized Xinjiang for the overcharging of tourists. Following the flood of online comments, the Xinjiang Culture and Tourism Department (新疆文旅) closed several Douyin comment sections.

Xinjiang’s efforts to go viral as a tourist destination show that it takes more than official propaganda to create a buzz – people are looking for genuineness, value, and that one special thing that makes it all worthwhile. During the summer of 2023, Xinjiang actually had an initial strong moment of domestic tourism recovery. After the pandemic years and strict zero Covid policies, many Chinese travelers were eager to experience something new and prioritized unique locations over a low budget. Now that the initial travel craze phase has passed, travelers are back to focusing on getting value for money and won’t accept being overcharged.

One definite upside of this marketing fail is that Chinese netizens very much appreciate how local Xinjiang residents gave travelers the heads up about the status quo. One commenter said, “After reading all the comments, I find Xinjiangers are so honest and lovely; this made me want to go visit! Maybe next time, they [local authorities] should promote their people instead.”

What’s Noteworthy

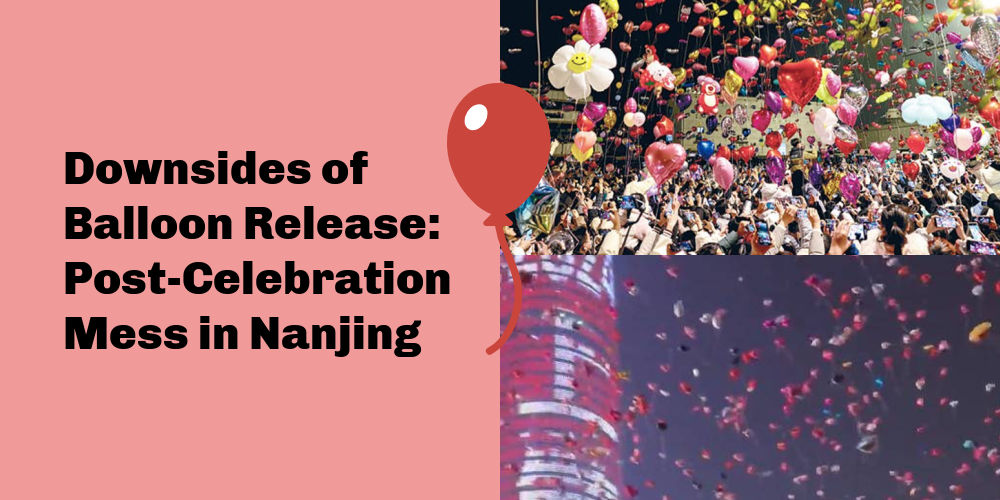

Tens of thousands of balloons were released into the sky during New Year’s Eve in Nanjing’s city center. While the scene created a spectacular count-down moment that went viral on social media, the aftermath wasn’t so pretty. In the week after the celebration, numerous balloons littered Nanjing’s commercial district — caught in trees, entangled in bushes, and even stuck on traffic lights.

To clean up this post-celebration mess, a local landscaping company was mobilized, with hundred workers utilizing multiple aerial work platforms and working around the clock for seven days to clear the Nanjing streets of the lingering balloons.

But the impact went well beyond Nanjing’s city center. Days after the event, balloons that were released in Nanjing were found as far as Hangzhou (#在杭州发现南京跨年夜气球#). Beyond the environmental impact and the extensive cleanup efforts, the use of hydrogen balloons also poses safety risks.

Hydrogen is highly flammable, and balloon encounters with high-voltage lines or open flames can result in explosions and significant damage. This actually also happened this New Year’s, creating hazardous situations for the crowds standing below the small, local explosions in the air (#跨年夜集体放飞气球引爆响#) – this is something that Chinese fire departments have also been warning about through online channels.

Nanjing is just one of the cities where thousands of balloons were released for New Year’s Eve; there were also major balloon release events in cities such as Chongqing, Chengdu, Xi’an, and Wuhan. On Weibo, numerous users have been vocal about highlighting the downsides and negative impact of these kinds of balloon releasing events.

What’s Popular

The Spring Festival holiday is known for its peak box office performances in China, with audiences eagerly anticipating the films released during this period. Last Lunar New Year, blockbuster hits like Wandering Earth II, Full River Red, and Hidden Blade made waves. This year, there’s considerable buzz around YOLO (热辣滚烫), the latest film from Chinese comedian and director Jia Ling.

Recently, Jia Ling emerged back into the spotlight after a year-long break from the public eye. On Weibo, the acclaimed actress shared that during this year, she directed her second film while also portraying the lead character. In this role, she plays a woman who drastically changes her life after being withdrawn from social life and who takes up boxing, for which Jia Ling shed approximately 100 pounds (50 kg).

Jia Ling’s remarkable weight loss for her upcoming film quickly became a trending topic, with her Weibo announcement garnering nearly 60,000 responses in just one day. Many view this dramatic change as a testament to Jia Ling’s incredible dedication to her work. After her successful and award-winning director’s debut Hi, Mom in 2021, this upcoming film is also expected to do very well during the holiday. YOLO (热辣滚烫) is set to premiere in Chinese theaters on February 10. Read more here👇.

What’s Memorable

As we’re back in the snow season, we’ve picked this article from our archive from one year ago which explores how and why Eileen Gu, the American-born freestyle skier and gold medallist, became an absolute viral sensation in China. Gu represented China in the 2022 Beijing Olympics and received praise for her excellent halfpipe World Cup performance during the 2023 Chinese New Year.

At the same time, Gu’s success also generated many discussions about her alleged privileged status, especially within the context of her being praised as a role model for Chinese (female) younger generations. Read here 👇

Weibo Word of the Week

“Southern Little Potatoes” | Our Weibo Word of the Week is “Southern Little Potatoes” (nánfāng xiǎo tǔdòu 南方小土豆).

The term “Southern Little Potatoes” (南方小土豆) is all the rage recently in the context of the hype surrounding Harbin. This ice-and-snow tourism season has seen a huge influx of tourists from the warmer southern regions who are heading north to the snow-blanketed Harbin or other destinations in the Three Northeastern Provinces (东北三省).

The southern tourists visiting China’s cold northeast tend to stand out due to their smaller stature, light-colored down jackets, and newly-bought winter hats. Their appearance not only contrasts with that of the typically taller and darker-dressed locals, but some people also think it makes them look like little potatoes. After the term ‘southern little potato’ became popular due to a viral video, some southern tourists, especially women, also adopted this term to humorously describe themselves.

The playful term quickly caught on, and locals started using it as a humorous marketing strategy to attract more southern visitors. Harbin street sellers are now selling plush keychains of “southern little potatoes,” and even local taxis are inviting the “baby potatoes” to get on board (土豆宝宝请上车) for complimentary rides. Through jokes, memes, and media stories about these ‘potatoes,’ a narrative has been constructed about the city of Harbin taking care of and pampering these ‘naive,’ ‘little’ visitors.

Although the term is meant to be affectionate, not everyone appreciates it. As the term predominantly refers to smaller women, some critics feel that by making “Southern Little Potatoes” (南方小土豆) part of its Ice and Snow economy promotion, Harbin is actually being somewhat chauvinistic and is contributing to sexism while reinforcing stereotypical perceptions of southern women.

While some critical bloggers are arguing that the term is harmful and derogatory, the majority of netizens are still using the term for light-hearted banter about the enthusiasm of southern visitors and the hospitality of the northerners welcoming them.

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Stories that are authored by the What's on Weibo Team are the stories that multiple authors contributed to. Please check the names at the end of the articles to see who the authors are.

You may like

China Insight

US-Russia Rapprochement and “Saint Zelensky”: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Shake-Up

From shifting sentiments on Zelensky to a renewed focus on Taiwan, recent geopolitical developments have sparked noteworthy takes from Chinese online commentators.

Published

1 day agoon

March 9, 2025

As the Russia-Ukraine war enters its fourth year, Chinese social media is once again flooded with discussions about the geopolitical shifts triggered by Trump’s policies. From the Oval Office clash to Trump’s ‘pivot’ to Russia, this article explores how Chinese netizens are interpreting the rapidly changing geopolitical landscape.

Three years ago, when the Russia-Ukraine war first broke out, one particular word went trending on Chinese social media: wūxīn gōngzuò (乌心工作). The term was a wordplay on the term wúxīn gōngzuò (无心工作), meaning not being in the mood to work, and it basically meant that people were too focused on Ukraine to concentrate on work.

Although that word has since faded from use online, recent geopolitical developments surrounding the Russia-Ukraine war have once again drawn considerable attention on Chinese social media, where trending word data tools show that “Trump” and “Zelensky” are among the hottest buzzwords of the moment.

Trump Zelensky, Ne Zha, Lei Jun; biggest words of interest on, among others, Weibo, on March 4, 2025.

Trump’s recent rhetoric toward Russia, his remarks about Ukraine, and his attitude toward NATO not only mark a shift from Biden and decades of US policy, but also reshuffle the geopolitical cards and raise questions about the future of the postwar international order.

Where does China stand in all this?

➜ Although China’s online environment is tightly controlled, particularly regarding political discussions, what stands out in conversations around the recent developments involving Trump, Putin, and Zelensky is a widespread sentiment that — at its core — it’s all about China.

Many believe that China’s rise on the global stage, and the resulting US-China rivalry, are key forces shaping US strategy toward Russia as well.

Woven into these discussions are US-China trade tensions, with Trump increasing tariffs by 10% on February 1, and then doubling the tariff on all Chinese imports to 20% from 10% on March 4. This immediately prompted China to retaliate with 10-15% tariffs on US agricultural products, effective March 10.

Currently, developments are unfolding so rapidly that one hashtag after another is appearing on Chinese social media. “It’s not that I don’t understand, it’s just that the world is changing so quickly,” one Weibo blogger commented, referencing a famous song by Cui Jian (“不是我不明白,是这世界变化快”).

Amid this whirlwind of events, let’s take a closer look at the current Chinese online discourse surrounding the Russia-Ukraine war, with a focus on shifting attitudes toward Zelensky and US-Russian relations.

THE OVAL OFFICE INCIDENT

“Saint Zelensky is a real man!”

One major moment in the recent developments has been the clash between Zelensky, Trump, and US Vice President JD Vance in the White House Oval Office on February 28.

Zelensky had come to the White House to discuss the US’s continued support against Russia and a potential deal involving Ukraine’s rare earth minerals, but it ended in a heated confrontation during which, among others, Zelensky questioned Vance’s notion of “diplomacy” with Putin, and Trump and Vance expressing frustration with what they perceived as Zelensky’s ingratitude for US support.

On Chinese social media, the clash between Zelensky, Trump, and Vance in the Oval Office seemingly caused a shift in public views towards Zelensky and the position of Ukraine. Some commentators who are known to usually take a pro-Russian stance were suddenly positive about Zelensky.

“Zelensky is really awesome, he had a confrontation with Putin’s two top negotiators in the Oval Office and still managed to hold his own,” historian Zhang Hongjie (@张宏杰) jokingly wrote on Weibo.

Others compared compared Trump and Vance to “two dogs barking” at Zelensky, and saw the meeting as one that was meant to humiliate Zelensky.

Nationalist blogging account “A Bad Potato” (一个坏土豆, 335k+ followers) admitted: “I’ll lay my cards on the table: I fully support Zelensky.”

He further wrote:

💬 “Let’s not make any illusions. Trump’s ultimate target is China. (..). He’s already added two rounds of 10% tariffs on China. Isn’t it obvious? Did you think he is pulling closer to Russia for some big China-Russia-America unification? Once he’s done dealing with his internal problems, he’ll inevitably come at China with full force. There are some people here who are hoping for Zelensky to kneel before the US, and I’d like to ask these people: Whose side are you on? Are you on the Russian or American side? When Zelensky’s firm towards the US, of course I’ll support him. His performance was so perfect that I’d like to call him Saint Zelensky!

(..) Some say Zelensky’s betraying his country. So what if he is? As long as he’s not selling out China, he can sell out the whole world for all I care. Just look at the stupid and bad Macron, or Starmer who’s full of sneaky tricks, they’re getting humiliated by Trump in all kinds of ways. Then look at Zelensky again and let me shout: Saint Zelensky is a real man! He’s a tough guy! Of course, I’m keeping it balanced here—I support Russia too. Both sides must make an effort.”

➜ Although there is some pragmatism in this ‘pro-Zelensky’ shift, which is Sino-centric and mostly based on which actors in the political game are considered antagonists of China, there is also another level of sympathy towards Zelensky as the underdog in this situation — facing a 2-against-1 dynamic on unfamiliar terrain, while speaking a language that is not his.

Weibo user “Uncle Bull” (@牛叔, 820k followers) wrote:

💬 “The arguing scene in the Oval Office should be a reminder for every politician that it doesn’t matter how well you speak English, when it’s a formal occasion, you should always speak your native language and have a translator with you— it helps avoid a lot of direct confrontations.”

In his analysis of the situation, well-known political commentator Chairman Rabbit (兔主席) took a far more critical stance towards Zelensky, suggesting that his confrontational attitude in the Oval Office was misplaced and driven by personal pride, and that his actions in the White House caused it to be “the most disastrous trip in history.”

Chairman Rabbit also commented:

💬 “There is an ancient Chinese saying: “A man of character can bow or stand tall as required [大丈夫能屈能伸].” When it comes to major issues like the survival of the nation, things like some dignity and righteousness and principles all are meaningless. When facing Trump, you just have to flatter and appease him. If Zelensky is unable to humble himself, then he’s probably not suited for this job. It’s just as the most pro-Ukraine Republican senator, Senator Lindsey Graham, said – he suggests that Zelensky should step down, and Ukraine should find someone else to negotiate.”

But there are many netizens who do not agree with him, like this popular comment saying: “Whatever you do, don’t kneel [to Trump] — you’re a spiritual totem (精神图腾) for so many people on Weibo.”

TRUMP’S ‘PIVOT’ TO RUSSIA

“The US-Russia honeymoon has begun”

When US and Russian delegates sat down in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, on February 18 to discuss improving Russia-US relations and ending the war in Ukraine—without Europe or Ukraine at the table—Chinese netizens pointed out that there were no plates on the table, joking that “Europe and Ukraine are what’s on the menu.”

They referred to a comment previously made by US Secretary of State Antony Blinken when replying to a question about US-China tensions leading to greater fragmentation: “If you’re not at the table in the international system, you’re going to be on the menu.”

The official Chinese response to the developments, as stated by Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Guo Jiakun (郭嘉昆), is that China is glad to see any efforts that contribute to peace, including any consensus reached between the US and Russia through negotiations (#中方回应俄美代表团举行会晤#).

Among social media users, there was banter about the sudden US-Russia rapprochement, after news came out that the two countries intend to cooperate on various matters concerning their shared geopolitical interests (#俄美决定未来将在多领域合作#).

“The US-Russian honeymoon has begun [美俄蜜月开始]!” some commenters concluded.

“It won’t last more than four years,” others predicted.

Some suggested it might be an opportunity for China and Europe to draw closer: “China and Europe will also cooperate on various matters.”

Regarding Putin agreeing to assist in US-Iran talks (#美媒爆普京同意协助美促成与伊朗核谈判#), reactions were cautiously optimistic: “It’s hard to find an American president seeking peace as much as Trump is,” one Weibo user wrote. Another added: “He might be pursuing ‘America First,’ but his efforts for peace deserve some acknowledgement. I hope it’s true.”

➜ Outside of China, analysts and commentators have argued that a US-Russia rapprochement could be bad for China, suggesting it might undermine the close strategic partnership between China and Russia. However, this sentiment seems less pronounced on Chinese social media, where many argue US-Russian relations are bound to be fickle, while others echo the official stance.

The official response to such concerns, as stated by Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Lin Jian (林剑), is that the China-Russia bilateral relationship “will not be affected by any third party”:

💬 “Both China and Russia have long-term development strategies and foreign policies. No matter how the international landscape changes, our relationship will move forward at its own pace. The US attempt to sow discord between China and Russia is doomed to fail.”

Another perspective comes from Chinese political scientist and commentator Zheng Yongnian (郑永年), in a recent interview with Xiakedao (@侠客岛), a popular commentary account from People’s Daily Overseas Edition.

Zheng noted that the US-Russia shift is not surprising—considering, among other things, Trump’s previous comments about his good relationship with Putin—but that it places Ukraine and Europe in an unfavorable position.

➜ Like other commentators, Zheng suggests that Trump’s strategy to improve ties with Russia is also linked to gaining leverage over China. However, he does not necessarily view it as a direct revival of Kissinger’s famous Cold War-era strategy, which aimed to align with China to counter the Soviet Union. In this case, it would be reversed: allying with Russia to counter China (“联俄抗中”). In Trump’s view, Zheng argues, Europe doesn’t matter, and Ukraine is insignificant. Russia is the key to maximizing US interests.

➜ Like others—and in contrast to some foreign analyses—Zheng does not see the U.S.-Russia rapprochement as necessarily harmful to China. Instead, he suggests that right-wing, pragmatic partners may ultimately be more beneficial to China than left-wing ideological ones, stating:

💬 “When it comes to the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the previous Biden administration continuously tried to frame China, attempting to shift the blame onto China. So now, after the US and Russian leaders spoke, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs responded by saying they are ‘pleased to see all efforts working for peace, including Russia and the US coming to a common understanding that will lead to peace.’ China won’t meddle in another country’s internal affairs. No matter who’s in power, we will engage with them. China can indeed take a relatively neutral stance.

In the past, we said, ‘It’s easier to deal with the right-wing in the West.’ Why? Because the political right is less hypocritical; they value interests, and interests can be exchanged. Some Western left-wing factions, however, cling to ideological patterns, labeling and defining you, making exchange and interaction impossible.”

SHARPENED FOCUS ON TAIWAN

“Ever since Trump came to power and betrayed Ukraine, the rhetoric towards Taiwan has become increasingly tough”

Although there may be mixed views and different analyses, one thing is certain: Trump’s strategies are shaking things up from how they used to be.

➜ One thing that doesn’t change in rapidly changing times, is an overall anti-American sentiment on Chinese social media.

Even though some commenters appreciate Trump’s pragmatism or are entertained by the spectacle of US politics from the sidelines, there remains a strong belief that US strategies are ultimately aimed against China. This reinforces anti-American sentiments and fuels discussions about a potential US-China conflict.

This is especially tangible at a time when the US government has once again raised tariffs on Chinese imports.

“If war is what the U.S. wants—be it a tariff war, a trade war, or any other type of war—we’re ready to fight till the end,” China’s embassy in Washington posted on X, reiterating a government statement from Tuesday.

During the Two Sessions on March 7, Foreign Minister Wang Yi (王毅) also commented on US-China relations, stating:

💬 “No country should harbor the illusion that it can suppress and contain China on one hand while seeking to develop a good relationships with China on the other. Such two-faced behavior [两面人] is not only detrimental to the stability of bilateral relations and cannot build mutual trust.”

➜ Against this backdrop, the Taiwan issue has once again come into sharp focus.

This is partly driven by the two Two Sessions (March 5-11), China’s annual gathering of the National People’s Congress (NPC) and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC). This is not just a major political event but also a key moment for propaganda and political messaging.

But it is mostly linked to the broader, rapidly changing geopolitical sphere and Trump’s shifting stance on Russia and Ukraine. The narrative of US power politics failing to change the course of a China-Taiwan “reunification” is surfacing again precisely because of Trump’s reshuffling of alliances.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Chinese social media users have frequently drawn comparisons between Taiwan and Ukraine. The phrase “Today’s Ukraine, tomorrow’s Taiwan?” gained traction at the time, as online commenters saw Ukraine’s rapid invasion as a cautionary tale for Taiwan, highlighting how quickly the situation could change. A viral meme from that period depicted a pig labeled “Taiwan” watching another pig, “Ukraine,” being slaughtered.

A meme circulating on social media in 2022 showing a pig “Taiwan” watching the slaughtering of another pig “Ukraine.”

This week, Chinese state media launched a large-scale social media propaganda campaign using strong language and clear visuals to reinforce the narrative that Taiwan is not a country, that it is part of China, and that reunification is inevitable.

Such rhetoric has appeared before, with similar peaks in Taiwan propaganda dating back to at least 2022. The topic of Taiwan has often been amplified during key political events, such as the 20th Party Congress and Xi Jinping’s speech in October 2022.

“Have you noticed?,” Weibo author Yangeisaibei (@雁归塞北) wrote: “Ever since Trump came to power and sold out Ukraine, the rhetoric towards Taiwan has become increasingly tough, the tones become more stern, and the words more straightforward.”

According to prominent Weibo blogger @前HR本人, who has over two million followers, the Taiwan issue is now more important than before.

💬 “When it comes to foreign struggles, resolving the Taiwan issue is China’s top priority. Judging from the Chinese Embassy in Washington declaring “We are not afraid of any kind of war with the US”, it seems we are already preparing to reunify Taiwan at any moment.”

Another Weibo blogger (@王江雨Law, 419k fans) wrote:

💬 “Now that all kinds of big and smaller developments are changing the [political] climate, especially if America’s strong territorial expansion claims turn into concrete actions, this could trigger synchronous reactions, greatly increasing the possibility of resolving the Taiwan issue within a few years. We need to rethink the previous view that the mainland is not in a hurry on this matter.”

What emerges from these discussions is that Chinese online discourse on the Russia-Ukraine war and US foreign policy is primarily centered around two key ideas:

🔸 The belief that China is ultimately at the core of US geopolitical strategies in its dealings with Russia.

🔸 A pragmatic, Sino-centric view in which support or opposition to leaders like Trump, Putin, or Zelensky shifts depending on what serves China’s interests best.

Rather than seeing the conflict in black-and-white terms, many Chinese netizens approach it as a dynamic political chess game, one in which China should play a smart and confident strategy.

Politics-focused blogger Mingshuzhatan (@明叔杂谈, 137k followers) wrote:

💬 “In the process of this game against US, we must respect them in tactics, and contempt them in strategy [战术上重视、战略上藐视] – stay patient and confident. Trump is currently going against the tide, he’s being destructive. But actually, this recklessness is damaging US credibility and its global influence, it will accelerate the decline of American hegemony. A silent majority of countries in the international community harbor growing resentment and disappointment toward the US, and when these sentiments reach a tipping point, America will truly experience the pain of “un unjust cause draws little support” [失道寡助]. China, on the other hand, although also facing some challenges, focuses on science and technological and industrial innovation. That’s the right path for China’s long-term stability, prosperity, and security. In the China-US competition, it is becoming increasingly evident that time is on China’s side.”

This perspective reflects a dominant theme across Chinese online discussions: No matter how intense the geopolitical shifts may be, or how much the US reshuffles its global strategy, China remains on its course and is playing the long game.🔚

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Military

“Li Jingjing Was Here”: Chinese Netizens React to Rumors of “Chinese Soldiers” in Russian Army

“We should tell Li Jingjing to come home. Risking your life on the battlefield for Russia is not worth it!”

Published

1 week agoon

March 3, 2025

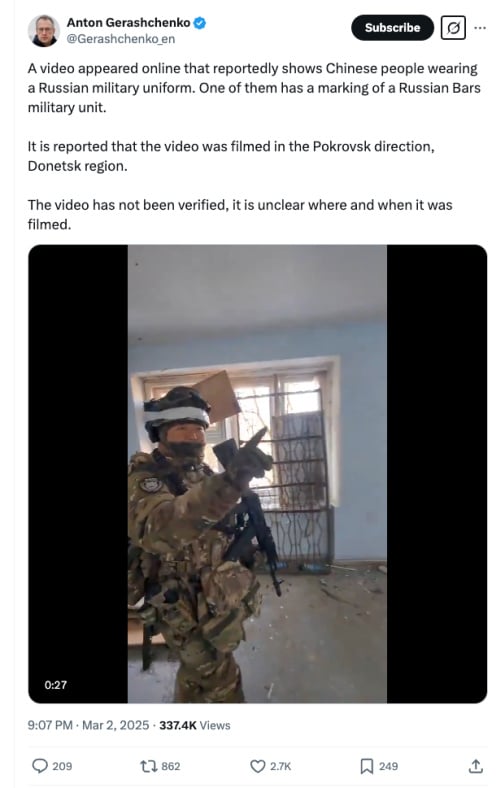

A video that has been making its rounds on X and Bluesky on March 2/3 has fueled speculation about whether Chinese nationals might be serving in Russian military units.

Ukrainian commentator and former adviser to Ukraine’s Minister of Internal Affairs, Anton Gerashchenko, posted:

“A video appeared online that reportedly shows Chinese people wearing a Russian military uniform. One of them has a marking of a Russian Bars military unit. It is reported that the video was filmed in the Pokrovsk direction, Donetsk region. The video has not been verified, it is unclear where and when it was filmed.”

The footage shows two soldiers inside an abandoned building, with one of them writing in Chinese on the wall: “Li Jingjing was here” (“李晶晶到此一游”). The two also exchange a few words in Chinese, saying things like, “Ah, I wrote it wrong again.” One of them wears an armlet belonging to BARS (Combat Army Reserve of Russia) military unit.

On one side of the wall, the words “-Wèi Precision Installation” (..卫精工安装) are written.

Other X accounts, including the influential Chinese account @whyyoutouzhele, pro-Ukrainian Oriannalyla (@Lyla_lilas) and UAVoyager (@NAFOvoyager) also posted the video on March 2nd, alleging that the footage came from Selydove, Donetsk region, and shows Chinese soldiers as part of Russian forces in the Pokrovsky direction. The source of the video posted by the second X user is the Telegram channel “Donbas Operative.”

Meanwhile, on Weibo, the same video is also being discussed by various commentators and netizens.

Digital & tech blogger ‘Ma Shang Tan” (@马上谈), who has over 480,000 followers on the platform, dismissed the rumors as fake, writing:

“Li Jingjing was here! Ukrainian media have published a condemning the presence of Chinese soldiers in the Russian camo… but that’s really too one-sided. Just because they write Chinese doesn’t mean they represent the Chinese people. First, Russia is offering high pay to recruit mercenaries, attracting people from all over the world who are willing to risk their lives for money. Second, as Russia continues to suffer losses, they’ve turned their focus to ethnic groups from the Far East, recruiting quite a few people in the army, many of whom will know Chinese characters.

Anyway, who even is this Li Jingjing? 😂😂😂😂”

Some commenters note that these soldiers “clearly aren’t Chinese,” some pointing to their appearance, others to how the characters were written—suggesting the characters are written “too wide.”

“This kindergarten level of characters is supposed to be written by a Chinese person?” another person wondered.

“I can immediately tell these are characters written by Koreans,” one Weibo user commented.

Since October 2024, South Korean intelligence has been reporting the presence of North Korean troops in Russia. However, their participation was never officially confirmed by Moscow or Pyongyang.

Another Weibo blogger, the military blogger “Earth Lens A” (@地球镜头A), with more than 950,000 followers, suggested that the “soldiers” could be Chinese, but that they are most likely people dressing up:

““Li Jingjing was here?” Ukrainian social media are framing it as if Chinese people are fighting in the war in the Russian forces. After fabricated claims of “North Koreans fighting in Kursk,” Ukrainian sources are now loudly claiming that Chinese troops have appeared near Pokrovsk, based on a random short video without any source.:

““…Precision Installation”? [“..精工安装”: referring to characters written on the wall in the abandoned building] These people wearing Russian military uniforms and speaking Chinese are either military enthusiasts from China doing cosplay or they’re some vloggers who went to Russia “pretending to be in combat.” Can’t say much else. Speaking of which, they should [do more to] control those Douyin and Kuaishou creators who claim to be fighting on the front lines.”

There is a thriving “cosplay culture” on Chinese short video platforms, and military cosplay is a part of that. Among Chinese younger people, cosplay (‘costume play’) has become increasingly popular over the past years. Cosplay allows people to become something they are not—a superhero, a villain, a sex symbol, a soldier—sometimes Chinese, American, Japanese, or Russian.

Some commenters allege that this particular video was made by creators on the video platform Bilibili, although there is currently no proof of that.

“It’s just some military fans playing in a dilapidated building,” another person wrote.

Meanwhile, there seems to be growing fascination over who Li Jingjing actually is.

“We should urge Li Jingjing to come home!” one blogger wrote: “It’s not worth dying on the Russian battlefield.”

They jokingly added: “Li Jingjing, your mom is calling you home for dinner!”

The phrase is a reference to a famous moment in Chinese internet history when a comment appeared on a World of Warcraft forum saying that a boy named Jia Junpeng was being called home for dinner by his mom (read here).

For some netizens, the fact that this video and its virality are being taken seriously on Western platforms seems to be a source of entertainment: “This video of Chinese cosplayers has started circulating on Twitter (X). It’s hard not to laugh watching their serious analysis.”

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

What’s on Weibo Chapters

Subscribe

Five Trending Proposals at the Two Sessions 🔍

US-Russia Rapprochement and “Saint Zelensky”: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Shake-Up

“Li Jingjing Was Here”: Chinese Netizens React to Rumors of “Chinese Soldiers” in Russian Army

How Ne Zha 2’s Shen Gongbao Became Known as the Ultimate “Small-Town Swot”

Beyond the Box Office: What’s Behind Ne Zha 2’s Success?

Our Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Why Chinese Hit Movie “Her Story” is ‘Good Stuff’: Stirring Controversy and Celebrating Female Perspectives

Chiung Yao’s Suicide Farewell Letter: An English Translation

12-Year-Old Girl from Shandong Gets Infected with HPV: Viral Case Exposes Failures in Protecting Minors

Weibo Watch: Christmas in China Is Everywhere and Nowhere

Breaking the Taboo: China’s Sanitary Pad Controversy Sparks Demand for Change

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

Weibo Watch: China’s Online Feminism Is Everywhere

Story of Chinese Female MA Graduate Going Missing for 13 Years Sparks Online Storm

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight10 months ago

China Insight10 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music11 months ago

China Music11 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital9 months ago

China Digital9 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

-

China Arts & Entertainment10 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment10 months agoSinging Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments