Newsletter

Weibo Watch: The Anti-Buzz

As we wrap up week 18 of 2023, let’s take a look at the top trends on Chinese social media. These are the main takeaways you need to know.

Published

2 years agoon

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #2 | READING TIME: 8 MIN

Dear Reader,

Welcome to Weibo Watch, the exclusive premium newsletter by What’s on Weibo that keeps you up-to-date on the latest stories and trends in Chinese social media and digital culture.

A small business owner in the Shandong city of Zibo had no idea what hit him when he saw thousands of visitors flocking to his shop. The industrial city of Zibo has been an online hit for weeks now, so he was used to seeing a large influx of travelers in the area. But now he himself had become the main attraction after a video in which a female tourist touched his muscles went viral overnight. What do you do when you suddenly see 180,000 visitors a day passing by your small duck’s head [鸭头, a Chinese snack] shop?

As described in one recent Chinese blog, the duck’s head seller is one of the latest “victims” of the ‘Zibo BBQ’ craze. By now, the incredible popularity of the barbecue city is also referred to as the “Zibo Phenomenon” (淄博现象). The city has been all over China’s social media top trending lists over the past week, and there are many discussions on how the city succeeded in becoming such a success, what it all means, and the downsides that come with it.

When a trend becomes excessively popular in a short span of time, it is almost inevitable for an anti-buzz to emerge. With high expectations, people tend to get disappointed easily. The larger the hype, the more significant the impact of even the slightest negative news.

What is striking about the recent Zibo discussions, is how it is triggering introspective debates on the dynamics of Chinese social media and the role played by online influencers and local authorities. However, there are divergent opinions among Chinese scholars, journalists, and bloggers who have written about this ‘Zibo Phenomenon.’ While some argue that it is all about free market governance and public participation, others suggest that the city’s success is actually the result of strict government control and influence.

The duck’s head shop owner probably won’t care a lot about all of these discussions. Although his hit status initially boosted sales, the crowds of people coming to his shop soon became so overwhelming that he could no longer run his business as usual (see video). As some even started harassing and physically assaulting him, he could no longer do his work and has now closed his shop. In a recent live stream, he tearfully talked about how his business, ironically, was ruined due to his viral success.

For all this and more, see our list of featured articles in this newsletter to dive deeper into the major trends that have recently attracted attention on Chinese social media. Also make sure to get the quick takes on social media, foreign affairs, and popular Chinese catchwords by Miranda Barnes, Thomas des Garets Geddes, and Andrew Methven in this week’s newsletter.

Got questions or suggestions? I always like to hear more about the China topics you’d like to know more about. Contact me via email or DM, or follow me on Twitter for the latest news and trends.

Best,

Manya

What to Know

Major trends to know:

- ▶︎ May Day holiday craze. The May Day “Golden week” holiday has come to an end. Travelers made 274 million trips within mainland China during the holiday, which exceeds pre-pandemic levels.

- ▶︎ King Charles III coronation. The coronation ceremony of King Charles III was also a big topic on Weibo and Douyin this weekend. noteworthy is that many of the top videos on the event were about the ‘not my king’ protests. China’s vice president Han Zheng arrived in London on Thursday for the coronation.

- ▶︎ Hotel guest finds dead body underneath bed. One Chinese man’s stay at a hotel in Lhasa turned into a nightmare when he discovered a corpse under the bed in which he had been sleeping. The man found the body after noticing a strong smell in his room. The incident led to a murder investigation and the arrest of a suspect.

- ▶︎ Chinese evacuated from Sudan. China successfully evacuated over 1,300 of its nationals from Sudan this week. The safe evacuation was met with praise online, where the mission was also called a “real life version” of Chinese blockbuster Homecoming.

- ▶︎ Chinese couple murdered in Bali? Two Chinese nationals, a 22-year-old female and a 25-year-old male, were found dead in their hotel room at the InterContinental hotel in Jimbaran, Bali. The male’s body was found on the balcony and the female’s body was found in the bathtub with wounds on her neck. While the cause of their deaths is still under investigation, the case has become a big topic on Chinese socials.

Note from the News Editor – by Miranda:

- ▶︎ Over the past week, the topic “How Can Ordinary People Have 10 Million in Assets” (普通人如何拥有千万资产) trended on Chinese social media. Some argued that owning a property in tier 1 cities like Beijing or Shanghai could already make you worth over 10 million yuan (just under $1.5 million). Many found the amount of money discussed to be out of touch with reality, as they struggle to cover their daily living costs and have no hope of ever amassing such wealth. The conversation eventually evolved into a broader discussion of achieving financial success.

- ▶︎ In the past 50 years, China has made significant economic strides, leading to an improved quality of life for its citizens. This progress is still remembered by the majority of Chinese citizens who have experienced huge improvements in their standard of living during their lifetime.

- ▶︎ In the late 90s, wàn yuán hù (万元户), meaning “household with over 10k assets” (under $1.5k), was a label of wealth status. However, the number 10 million yuan now seems much harder to attain. This raises concerns about social mobility, as most people interested in the topic are “ordinary” or have not yet amassed that much wealth. It seems that hard work and opportunities may no longer be enough to achieve financial success, but that shouldn’t stop people from dreaming.

Sinification’s foreign affairs views from China – by Thomas:

- ▶︎ One of China’s most eminent international relations experts, Yan Xuetong (阎学通), recently warned Chinese businesses to brace themselves for a rough ride over the coming couple of decades. He bemoaned the current dire state of US-China relations and the fractures this is creating across the world.

- ▶︎ In Yan’s words: “I am now in my 70s and when we were children in the 50s and 60s we grew up cursing US leaders. Since Nixon’s visit to China in ’72, China stopped naming and shaming the American leadership. [However,] after Trump came to power, we resumed naming and shaming them, calling Pompeo an enemy of mankind. How far [down] do you want bilateral relations to go? During my most recent visit to the US, I felt that the perception of China in America had also seriously deteriorated. I met some of our overseas students who told me that American students would not say it out loud, but that everyone knows that they harbour a lot of hostility towards Chinese students.”

- ▶︎ For more in-depth takes on foreign affairs as viewed from China, subscribe to the Sinification newsletter by Thomas des Garets Geddes here.

What’s Trending

1: “College Student Special Forces” (大学生特种兵) | This Labor Day holiday, ‘special forces travelers’ were flooding popular tourist spots across China. Their mission is clear: covering as many places as possible at the lowest cost and within a limited time. While the travel trend has become a social media hype, there are also those criticizing the trend for being superficial and troublesome.

2: Consumerism and Empty Social Spectacle | Fast, fun, BBQ travel is a major topic on Chinese social media these days. Chinese journalist & academic Liu Yadong reposted a noteworthy short essay by the WeChat account Jiuwenpinglun in which the author argued that the hype surrounding Zibo barbecue is a symptom of a “sick society” in which people are disconnected from meaningful topics. While serious social issues are muted and superficial marketing tricks are blasted all over the internet, China’s “hypocritical youth” actively participate in the societal emptiness they say they reject. We translated the controversial for you:

3: Why Zibo’s Strength Is Also Its Weakness | It’s like a Shandong ‘Disneyland,’ but with more people and longer lines. The city of Zibo has become a major tourist attraction, filled with lively atmosphere, cheap BBQ, and friendly people. But local business owners also face the downsides of operating in a city that has become so extremely popular. In this feature article, we wrap up some of the latest controversies and discussions surrounding the Zibo trend.

What’s Noteworthy

China’s Most Famous Kindergarten Teacher | Teacher Huang (黄老师在) from Wuhan suddenly became China’s most beloved kindergarten teacher this week after she uploaded a video of herself singing the “Digging in the Garden” (挖呀挖). The video soon went viral, receiving millions of views. Huang became a social media sensation, not only because of her enthusiasm and warmth, but also because of the catchy song itself. The video also spawned a trend in which netizens uploaded their own versions of the song. There were some rumors that Huang actually was an online influencer, but they were later refuted. Nevertheless Huang received a lot of online hate: she is allegedly not qualified to teach, and there are legal questions over the copyright of the song she sang. With her latest livestream, Huang earned more than enough money to take some time off – which she did.

What’s Popular

The First Slam Dunk | The Japanese animated film The First Slam Dunk (灌篮高手) premiered in mainland China two weeks ago, earning $13.8m on its opening day. The movie is still top trending in the movie category now on Baidu top trends now. The First Slam Dunk is an adaptation from the 1990s Japanese basketball manga/anime series about high school and youth romance. The manga was a major hit in Japan, but also in China, where the new, award-winning movie is now bringing back a lot of ’90s nostalgy for many moviegoers. Watch the official trailer here:

What’s Memorable

Vagrant Shanghai Professor (上海流浪大师) | For this week’s pick from the archives, and especially in light of the buzz/anti-buzz theme, we’ve selected an article from 2019, when the popular short-video app Douyin flooded with videos of the so-called “Vagrant Shanghai Professor” (上海流浪大师). The homeless man, who eloquently discussed literature and philosophy, went viral on Chinese social media after someone posted a video of him. Within a few days after the first video of him went viral, hundreds of people began searching for him in the streets, disturbing his peace and quiet. When the crowds became too big, the Shanghai police had to intervene for his own safety. We could not find any updates about his current whereabouts but hope that the man – who never wished to go viral – has since found the peaceful life he longed for. Read more here:

Weibo Word of the Week – by Andrew

Our Weibo Word of the Week is nóngguǎn (农管), which translates as “agricultural-management officers.” Nóngguǎn 农管 has been a trending topic on Weibo over the last week. It’s a nickname given to a new rural police force recently announced by China’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. According to the ministry, its officers will bring much-needed law enforcement to China’s countryside: catching sellers of counterfeit or substandard seeds, pesticides and veterinary medicines, and inspecting animals and plants for disease.

But the reception online so far has been very negative. Many netizens fear they will be like the much disliked urban equivalent, known as “urban-management officers”, or chéngguǎn 城管, who are among China’s most despised law enforcers. The chéngguǎn are generally disliked for their abuse of street vendors and record of violence. Due to this, there is a fear that the newly introduced village officials may not be any better in their conduct towards the residents they are meant to serve. You can read more about how these discussions are unfolding online in this week’s Slow Chinese.

Want to learn more Chinese? Subscribe to Andrew Methven’s super insightful Slow Chinese free newsletter here.

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Stories that are authored by the What's on Weibo Team are the stories that multiple authors contributed to. Please check the names at the end of the articles to see who the authors are.

You may like

Newsletter

TikTok Refugees, Xiaohongshu, and the Letters from Li Hua

Published

4 days agoon

January 19, 2025

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #43

Overview:

▶ Dear Reader – “Dear Li Hua”: Explaining the TikTok Xiaohongshu Honeymoon

▶ What’s on Weibo Chapters – 15 Years of Weibo

▶ What’s Popular – ‘Black Myth Wukong’ at Spring Festival

▶ What’s Memorable – Fleeing to Iceland

Dear Reader,

Imagine you are Li Hua (李华), a Chinese senior high school student. You have a foreign friend, far away, in America. His name is John, and he has asked you for some insight into Chinese Spring Festival, for an upcoming essay has to write for the school newspaper. You need to write a reply to John, in which you explain more about the history of China’s New Year festival and the traditions surrounding its celebrations.

This is the kind of writing assignment many Chinese students have once encountered during their English writing exams in school during the Gaokao (高考), China’s National College Entrance Exams. The figure of ‘Li Hua’ has popped up on and off during these exams since at least 1995, when Li invited foreign friend ‘Peter’ to a picnic at Renmin Park.

Over the years, Li Hua has become somewhat of a cultural icon. A few months ago, Shangguan News (上观新闻) humorously speculated about his age, estimating that, since one exam mentioned his birth year as 1977, he should now be 47 years old—still a high school student, still helping foreign friends, and still introducing them to life in China.

This week, however, Li Hua unexpectedly became a trending topic on social media—in a week that was already full of surprises.

With a TikTok ban looming in the US (delayed after briefly taking effect on Sunday), millions of American TikTok users began migrating to other platforms this month. The most notable one was the Chinese social media app Xiaohongshu (now also known as Rednote), which saw a massive influx of so-called “TikTok refugees” (Tiktok难民). The surge propelled Xiaohongshu to the #1 spot in app stores across the US and beyond.

This influx of some three million foreigners marked an unprecedented moment for a domestic Chinese app, and Xiaohongshu’s sudden international popularity has brought both challenges and beautiful moments. Beyond the geopolitical tension between the US and China, Chinese and American internet users spontaneously found common ground, creating unique connections and finding new friends.

While the TikTok/Xiaohongshu “honeymoon” may seem like just a humorous trend, it also reflects deeper, more complex themes.

✳️ National Security Threat or Anti-Chinese Witchhunt?

At its core, the “TikTok refugee” trend has sprung from geopolitical tensions, rivalry, and mutual distrust between the US and China.

TikTok is a wildly popular AI-powered short video app by Chinese company ByteDance, which also runs Douyin, the Chinese counterpart of the international TikTok app. TikTok has over 170 million users in the US alone.

A potential TikTok ban was first proposed in 2020, amid escalating US-China tensions. President Trump initiated the move, citing security and data concerns. In 2024, the debate resurfaced in global headlines when President Biden signed the “Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act,” giving ByteDance nine months to divest TikTok or face a US ban.

TikTok, however, has continuously insisted it is apolitical, does not accept political promotion, and has no political agenda. Its Singaporean CEO Shou Zi Chew maintains that ByteDance is a private business and “not an agent of China or any other country.”

🇺🇸 From Washington’s perspective, TikTok is viewed as a national and personal security threat. Officials fear the app could be used to spread propaganda or misinformation on behalf of the Chinese Communist Party.

🇨🇳 Beijing, meanwhile, criticizes the ban as an act of “bullying,” accusing the US of protectionism and attempting to undermine China’s most successful internet companies. They argue that the ban reflects America’s inability to compete with the success of Chinese digital products, labeling the scrutiny around TikTok as a “witch hunt.”

Political cartoon about the American “witchhunt” against TikTok, shared on Weibo in 2023, also published on Twitter by Lianhe Zaobao.

“This will eventually backfire on the US itself,” China’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin predicted in 2024.

Wang turned out to be quite right, in a way.

When it became clear in mid-January that the ban was likely to become a reality, American TikTok users grew increasingly frustrated and angry with their government. For many of these TikTok creators, the platform is not just a form of entertainment—it has become an essential part of their income. Some directly monetize their content through TikTok, while others use it to promote services or products, targeting audiences that other platforms like Facebook, Instagram, or X can no longer reach as effectively.

Initially, the mass migration of American users to Xiaohongshu was a symbolic protest against US policies. Users advocated for the right to choose their preferred social media, and voiced their frustration at how their favorite app had become a pawn in US-China geopolitical tensions. Rejecting the narrative that “data must be protected from the Chinese,” many pointed out that privacy concerns were equally valid for US-based platforms. As an act of playful political defiance, these users downloaded Xiaohongshu to demonstrate they didn’t fear the government’s warnings about Chinese data collection.

(If they had the option, by the way, they would have installed Douyin—the actual Chinese version of TikTok—but it is only available in Chinese app stores, whereas Xiaohongshu is accessible in international stores, so it was picked as ‘China’s version of TikTok.’)

Xiaohongshu is actually not the same as TikTok at all. Founded in 2013, Xiaohongshu (literal translation: Little Red Book) is a popular app with over 300 million users that combines lifestyle, travel, fashion, and cosmetics with e-commerce, user-generated content, and product reviews. Like TikTok, it offers personalized content recommendations and scrolling videos, but is otherwise different in types of engagement and being more text-based.

As a Chinese app primarily designed for a domestic audience, the sudden wave of foreign users caused significant disruption. Xiaohongshu must adhere to the guidelines of China’s Cyberspace Administration, which requires tight control over information flows. The unexpected influx of foreign users undoubtedly created challenges for the company, prompting a scramble to recruit English-speaking content moderators to manage the new streams of content. Foreigners addressing sensitive political issues soon found their accounts banned.

Of course, there is undeniable irony in Americans protesting government control by flocking to a Chinese app functioning within an internet system that is highly controlled by the government—a move that sparked quite some debate and criticism as well.

✳️ The Sino-American ‘Dear Li Hua’ Moment

While the initial hype around Xiaohongshu among TikTok users was political, the trend quickly shifted into a moment of cultural exchange. As American creators introduced themselves on the platform, Chinese users gave them a warm welcome, eager to practice their English and teach these foreign newcomers how to navigate the app.

Soon, discussions about language, culture, and societal differences between China and the US began to flourish. Before long, “TikTok refugees” and “Xiaohongshu natives” were collaborating on homework assignments, swapping recipes, and bonding through humor.

For instance, Chinese users jokingly asked the “TikTok refugees” to pay a “cat tax” for seeking refuge on their platform, which American users happily fulfilled by posting adorable cat photos. American users, in turn, joked about becoming best friends with their “Chinese spies,” playfully mocking their own government’s fears about Chinese data collection.

The newfound camaraderie sparked creativity, as users began generating humorous images celebrating the bond between American and Chinese netizens—like Ronald McDonald cooking with the Monkey King or the Terra Cotta Soldier embracing the Statue of Liberty. Later, some images even depicted the pair welcoming their first “baby.”

🇺🇸 At the same time, it became clear just how little Americans and Chinese truly know about each other. Many American users expressed surprise at the China they discovered through Xiaohongshu, which contrasted sharply with negative portrayals they’ve seen in the media. While some popular US narratives often paint Chinese citizens as “brainwashed” by their government, many TikTok users began to reflect on how their own perspectives had been shaped—or even “manipulated”—by their media and government.

🇨🇳 For Chinese users, the sudden interaction underscored their digital isolation. Over the past 15 years, China has developed its own tightly regulated digital ecosystem, with Western platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube inaccessible in the mainland. While this system offers political and economic advantages, it has left many young Chinese people culturally hungry for direct interaction with foreigners—especially after years of reduced exchange caused by the pandemic, trade tensions, and bilateral estrangement. (Today, only some 1,100 American students are reportedly studying in China.)

The enthusiasm and eagerness displayed by American and Chinese Xiaohongshu users this week actually underscores the vacuum in cultural exchange between the two nations.

As a result of the Xiaohongshu migration, language-learning platform Duolingo reported a 216% rise in new US users learning Mandarin—a clear sign of growing interest in bridging the US-China divide.

Mourning the lack of intercultural communication and celebrating this unexpected moment of connection, Xiaohongshu users began jokingly asking Americans if they had ever received their “Li Hua letters.”

What started as some lighthearted remarks evolved into something much bigger as Chinese users dug up their old Gaokao exam papers and shared the letters they had written to their imaginary foreign friends years ago. These letters, often carefully stored in drawers or organizers, were posted with captions like, “Why didn’t you reply?” suggesting that Chinese students had been trying to reach out for years.

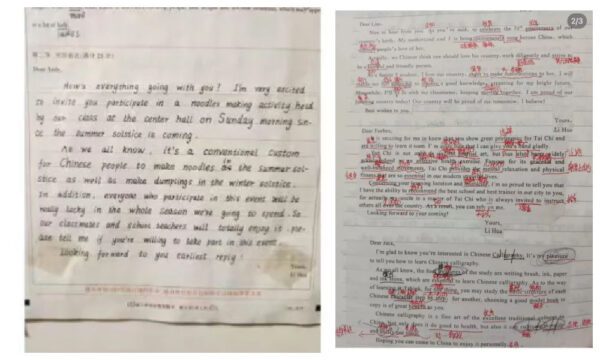

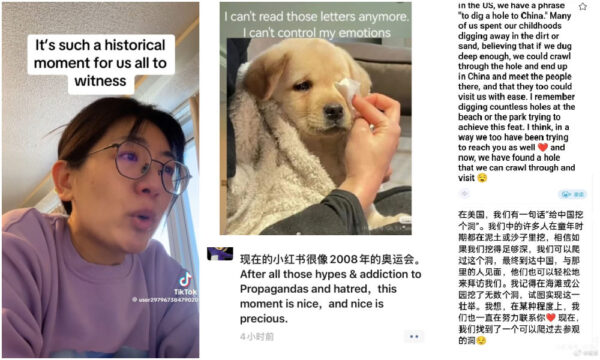

Example letters on Xiaohongshu: ‘Li Hua’ writing to foreign friends.

The story of ‘Li Hua’ and the replies he never received struck a chord with American Tiktok users. One user, Debrah.71, commented:

“It was the opposite for us in the USA. When I was in grade school, we did the same thing—we had foreign pen pals. But they did respond to our letters.”

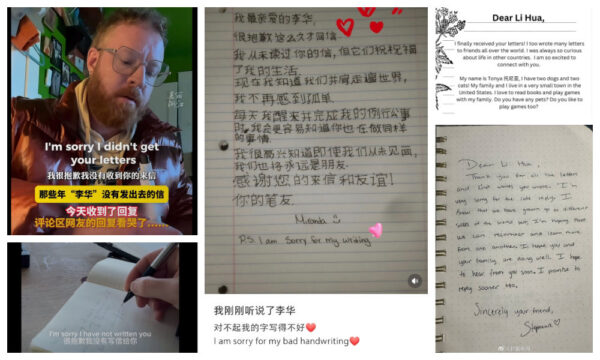

Then, something extraordinary happened: Americans started replying to Li Hua.

One user, Douglas, posted a heartfelt video of him writing a letter to Li Hua:

📝”Dear Li Hua, I’m sorry I didn’t get your letters. I understand you’ve been writing me for a long time, but now I’m here to reply. Hello, from your American friend. I hope you’re well. Life here is pretty normal—we go to work, hit the gym, eat dinner, watch TV. What about you? Please write back. I’m sorry I didn’t reply before, but I’m here now. Your friend, Douglas.”

Another user, Tess (@TessSaidThat), wrote:

📝”Dear Li Hua, I hope this letter finds you well. I’m so sorry my response is so late. My government never delivered your letters. Instead, they told me you didn’t want to be my friend. Now I know the truth, and I can’t wait to visit. Which city should I visit first? With love, Tess.”

Examples of Dear Li Hua letters.

Other replies echoed similar sentiments:

📝”Dear Li Hua, I’m sorry the world kept us apart.”

📝”Did you achieve your dreams? Are you still practicing English? We’re older now, but wherever we are, happiness is what matters most.”

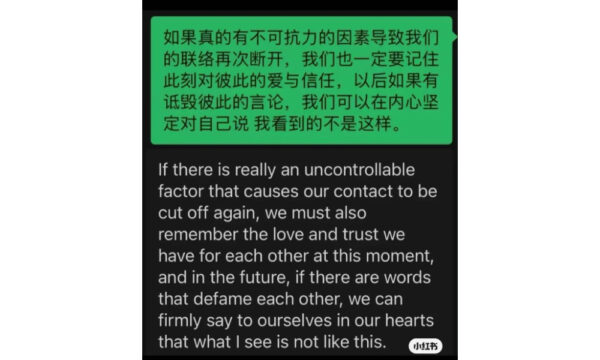

These exchanges left hundreds of users—both Chinese and American, young and old, male and female—teary-eyed. In a way, it’s the emotional weight of the distance—represented by millions of unanswered letters—that resonated deeply with both “TikTok refugees” and “Xiaohongshu natives.”

Emotional responses to the Li Hua letters.

The letters seemed to symbolize the gap that has long separated Chinese and American people, and the replies highlighted the unusual circumstances that brought these two online communities together. This moment of genuine cultural exchange made many realize how anti-Chinese, anti-American sentiments have dominated narratives for years, fostering misunderstandings.

Xiaohongshu commenter.

On the Chinese side, many people expressed how emotional it was to see Li Hua’s letters finally receiving replies. Writing these letters had been a collective experience for generations of Chinese students, creating messages to imaginary foreign friends they never expected to meet.

Receiving a reply wasn’t just about connection; it was about being truly seen at a time when Chinese people often feel underrepresented or mischaracterized in global contexts. Some users even called the replies to the Li Hua letters a “historical moment.”

✳️ Unity in a Time of Digital Divide

Alongside its political and cultural dimensions, the TikTok/Xiaohongshu “honeymoon” also reveals much about China and its digital environment. The fact that TikTok, a product of a Chinese company, has had such a profound impact on the American online landscape—and that American users are now flocking to another Chinese app—showcases the strength of Chinese digital products and the growing “de-westernization” of social media.

Of course, in Chinese official media discourse, this aspect of the story has been positively highlighted. Chinese state media portrays the migration of US TikTok users to Xiaohongshu as a victory for China: not only does it emphasize China’s role as a digital superpower and supposed geopolitical “connector” amidst US-China tensions, but it also serves as a way of mocking US authorities for the “witch hunt” against TikTok, suggesting that their actions have ultimately backfired—a win-win for China.

The Chinese Communist Party’s Publicity Department even made a tongue-in-cheek remark about Xiaohongshu’s sudden popularity among foreign users. The Weibo account of the propaganda app Study Xi, Strong Country, dedicated to promote Party history and Xi Jinping’s work, playfully suggested that if Americans are using a Chinese social media app today, they might be studying Xi Jinping Thought tomorrow, writing: “We warmly invite all friends, foreign and Chinese, new and old, to download the ‘Big Red Book’ app so we can study and make progress together!”

Perhaps the most positive takeaway from the TikTok/Xiaohongshu trend—regardless of how many American users remain on the app now that the TikTok ban has been delayed—is that it demonstrates the power of digital platforms to create new, transnational communities. It’s unfortunate that censorship, a TikTok ban, and the fragmentation of global social media triggered this moment, but it has opened a rare opportunity to build bridges across countries and platforms.

The “Dear Li Hua” letters are not just personal exchanges; they are part of a larger movement where digital tools are reshaping how people form relationships and challenge preconceived notions of others outside geopolitical contexts. Most importantly, it has shown Chinese and American social media users how confined they’ve been to their own bubbles, isolated on their own islands. An AI-powered social media app in the digital era became the unexpected medium for them to share kind words, have a laugh, exchange letters, and see each other for what they truly are: just humans.

As millions of Americans flock back to TikTok today, things will not be the same as before. They now know they have a friend in China called Li Hua.

Best,

Manya

(@manyapan)

PS There is a lot more to say about this topic, and if you’d like to read more, I’d also recommend reading Wen Hao’s Newsletter: “American TikTok users and Beijing found their common villain—the United States.”

What’s on Weibo Chapters

Especially in these tumultuous TikTok and Xiaohongshu times, I’m excited to share the first long read of What’s on Weibo Chapters with you. This month, our theme is 15 Years of Weibo and this is a relevant read to understand the dynamics of Chinese social media.

“15 Years of Weibo: The Evolution of China’s Social Media Giant,” explores how Weibo became one of the most successful social media platforms in China’s internet history. It examines its strategies, struggles, and its role in shaping the country’s digital landscape—past, present, and future.

Here are some key questions the article addresses:

➡️What was China’s social media landscape like in the pre-Weibo era?

➡️Why did Sina Weibo succeed while other platforms failed?

➡️How has Weibo shaped public opinion and discourse in China?

➡️What is Weibo’s current role in China’s social media ecosystem?

➡️What are the prospects for Weibo’s future?

If you’re curious about any of these questions, this article has you covered. From its beginnings as ‘Chinese Twitter’ to its evolution into a digital dinosaur, the story of Weibo offers a window into China’s broader social media landscape.

What’s Popular

Is Chinese game sensation ‘Black Myth Wukong’ making a jump from gaming screens to the CMG Spring Festival Gala?

The countdown to the most-watched show of the year has begun. On January 29, the Year of the Snake will be celebrated across China, and as always, the CMG Spring Festival Gala, broadcast on CCTV1, will air on the night leading up to midnight on January 28.

Rehearsals for the show began last week, sparking rumors and discussions about the must-watch performances this year. Soon, the hashtag “Black Myth: Wukong – From New Year’s Gala to Spring Festival Gala” (#黑神话悟空从跨晚到春晚#) went viral on Weibo, following rumors that the Gala will feature a performance based on the hugely popular game Black Myth: Wukong.

Three weeks ago, a 16-minute-long Black Myth: Wukong performance already was a major highlight of Bilibili’s 2024 New Year’s Gala (B站跨年晚会). The show featured stunning visuals from the game, anime-inspired elements, special effects, spectacular stage design, and live song-and-dance performances. It was such a hit that many viewers said it brought them to tears. You can watch that show on YouTube here.

While it’s unlikely that the entire 16-minute performance will be included in the Spring Festival Gala (it’s a long 4-hour show but maintains a very fast pace), it seems highly possible that a highlight segment of the performance could make its way to the show.

Recently, Black Myth: Wukong was crowned 2024’s Game of the Year at the Steam Awards. The game is nothing short of a sensation. Officially released on August 20, 2024, it topped the international gaming platform Steam’s “Most Played” list within hours of its launch. Developed by Game Science, a studio founded by former Tencent employees, Black Myth: Wukong draws inspiration from the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West. This legendary tale of heroes and demons follows the supernatural monkey Sun Wukong as he accompanies the Tang Dynasty monk Xuanzang on a pilgrimage to India to retrieve Buddhist scriptures. The game, however, focuses on Sun Wukong’s story after this iconic journey.

The success of Black Myth: Wukong cannot be overstated—I’ve also not seen a Chinese video game be this hugely popular on social media over the past decade. Beyond being a blockbuster game it is now widely regarded as an impactful Chinese pop cultural export that showcases Chinese culture, history, and traditions. Its massive success has made anything associated with it go viral—for example, a merchandise collaboration with Luckin Coffee sold out instantly.

If Black Myth: Wukong does indeed become part of the Spring Festival Gala, it will likely be one of the most talked-about and celebrated segments of the show. If it does not come on, which we would be a shame, we can still see a Black Myth performance at the pre-recorded Fujian Spring Festival Gala, which will air on January 29.

Lastly, if you’re not into video games and not that interested in watching the show, I still highly recommend that you check out the game’s music. You can find it on Spotify (link to album). It will also give you a sense of the unique beauty of Black Myth: Wukong that you might appreciate—I certainly do.

What’s Memorable

Social media can bring out the worst in people, but sometimes it also brings out the best. We saw this over the past week in the special moments shared between American ‘TikTok refugees’ and Chinese Xiaohongshu users. As they exchanged jokes online, it reminded me of a short but memorable trend that erupted on Weibo during the Covid era.

After the Embassy of Iceland posted about its bustling ‘post-pandemic’ travel season—suggesting that the Covid-19 “gloom is over”—jealousy spread among Chinese netizens. Seeing images of people having picnics and celebrating life in beautiful Iceland, many on Weibo suddenly began posing as natives of Iceland, claiming to feel homesick and longing to return to their “homeland.”

Others jokingly referred to themselves as Covid “refugees,” humorously trying to gain access to Iceland. One popular comment read: “I was abducted from Iceland at the age of three and taken to Henan.”

While the Embassy’s post served as a stark reminder of the contrast between China and other countries in handling Covid, it also provided a much-needed opportunity for online banter and sarcasm—momentarily making Chinese netizens feel a little closer to Iceland.

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Newsletter

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

About balloons, drone dragons, changes coming to What’s on Weibo, and much more.

Published

2 weeks agoon

January 7, 2025

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #42

This week’s newsletter:

◼︎ 1. Editor’s Note – A New Chapter

◼︎ 2. What’s New – A closer look at featured stories

◼︎ 3. What’s Trending – Hot highlights

◼︎ 4. What’s Noteworthy – A strange record

◼︎ 6. What’s Popular – Jackson Yee’s stellar performance

◼︎ 7. What’s Memorable – Looking back at the 10 most-read stories of 2024

Dear Reader,

From Hangzhou to Wuhan, the New Year in China was celebrated with the release of thousands of balloons at midnight in cities across the country. In Hangzhou alone, approximately 70,000 people attended the New Year countdown celebrations, with some bloggers estimating that street vendors sold at least 20,000 balloons in one night. In Nanchang, the capital of Jiangxi province, thousands of people also released balloons in the city center, resulting in stunning crowd videos (see here).

While a sky filled with balloons makes for some spectacular images and footage, adding to the festive sphere, there are also worries about this contemporary ‘tradition.’

The Nanchang balloon moment at midnight.

The sight of tens of thousands of people gathering in city centers, such as in Nanchang, has triggered discussions about the dangers of unexpected incidents leading to panic, potentially causing stampedes like the tragic event in Shanghai a decade ago.

Beyond crowd safety, the release of thousands of balloons introduces another serious risk. Hydrogen-filled balloons (hydrogen is often illegally used in balloons because it’s cheaper than helium) are highly flammable, and contact with high-voltage lines or open flames can lead to explosions and hazardous situations. One such incident occurred in Xinyang on New Year’s Eve, when balloons exploded at the crowded entrance of a shopping mall (video). In Hangzhou, a 22-year-man was arrested at the scene for setting off fireworks in Hangzhou during the balloon release festivities, also causing local explosions.

And then, there are concerns about the environmental impact. The balloon release festivities in Hangzhou alone resulted in an estimated six tons of garbage being left behind, making the cleanup a massive and costly undertaking. While sanitation workers are mobilized to tackle the mess, many balloons end up caught in trees, tangled in bushes, or drifting so far that they’re beyond the reach of cleanup crews. The sheer amount of plastic waste left behind has sparked online discussions, with many questioning the environmental consequences of these celebrations.

So what’s the alternative?

This year, you might have seen a viral video of an impressive drone show supposedly held on the Bund in Shanghai, featuring a dragon formed by dozens of drones dancing in the night sky, crowned by a circle of fireworks. The video went viral across Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, and X. Even Elon Musk liked the video, tweeting his “wow” comment: look how China celebrates the New Year!

The video, however, turned out to be fake. In fact, there was no show for New Year’s at the Bund at all.

The video creator combined elements from various other videos, including a drone light show featuring a majestic dragon that took place in Shenzhen on October 1st, marking the 75th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China (video).

The glowing circle in the sky was from a firework and AI show held in Liuyang, Hunan, on December 7, titled “Tears of the Gate of Heaven” (天空之门的眼泪). The falling lights symbolized tears from heaven and were designed by a local firework company boss to commemorate his late mother (video).

Upon further research, I found that the Liuyang show had inspired a series of edited videos, placing the Liuyang show highlight in different locations, with each version more spectacular than the last (see examples). As reported by Annielab, there are even online tutorials teaching netizens how to digitally insert the Liuyang ‘gate’ into different backgrounds with the Jianying (剪映, aka Capcut) editing app.

What began as an online meme (“I haven’t been to the Liuyang show, but I can bring it to my town”) eventually resulted in the viral video combining the Shenzhen and Liuyang shows against the backdrop of the Bund. For the quick scrollers, it apparently was so realistic that even Elon Musk thought it was genuine.

Stills from the fake drone dragon video.

The fake drone dragon New Year video is interesting for several reasons. It highlights how quickly fake news about China spreads across social media, with few questioning the authenticity of viral posts—even when they’re shared with millions of followers. We’ve seen this pattern before, with stories about the social credit system, a supposed Xi Jinping chatbot, and heavily edited cyberpunk-style Chongqing scenes.

These trends often repeat themselves, portraying China in extremes: either as a futuristic utopia or a dystopian threat. They go viral because they serve as clickbait, used by both hostile “anti-China” accounts and propaganda-heavy “pro-China” accounts to push their narratives—look how great China is or look how scary China is.

The dragon video, though fake, also underscores China’s role as a global tech power. Its components—real drone and AI shows in Liuyang, Shenzhen, and other cities—demonstrate just how advanced the technology has become, to the point where reality and fabrication are increasingly difficult to distinguish.

It’s just a video, but it points to something bigger: the lack of understanding about what is actually happening in China. Whether it’s about China’s digital space or society at large, most people don’t take the time—or simply don’t have the time—to look beyond the surface of fast-moving stories. This tendency risks amplifying misconceptions. Before you know it, you might retweet a fake dragon video, interpreting it as evidence of a powerful or intimidating China, without realizing it’s part of a broader grassroots trend that’s misunderstood—or missing the fact that, for now, far more balloons than drones still rise into the skies during New Year’s celebrations.

Before I wander off with the balloons, what’s the takeaway? As we step into 2025, with AI playing an ever-growing role on social media and global influencers shaping the news we consume—often with their own agendas—it’s more important than ever to examine the stories we amplify critically. Only by paying attention to the details can we truly understand the bigger picture.

Announcing some changes to What’s on Weibo

This brings me to an exciting new chapter for What’s on Weibo and how I see the future of the site. The China-focused global news environment has evolved significantly since I first started this platform. There’s now an increased focus in mainstream media on China’s social media trends, and niche China-related news has become accessible to many thanks to innovative tools at our fingertips. While there’s more information than ever, it’s also becoming increasingly chaotic and fleeting.

As a smaller, independent voice in this fast-paced and crowded media arena, I’m committed to offering you unique and meaningful insights into Chinese society and digital culture that you won’t find anywhere else. In this video, I’ll explain the changes coming to the site, introducing What’s on Weibo Chapters. In these turbulent, dragon-drone times, I hope you’ll appreciate this new chapter for What’s on Weibo.

Our first Chapter, of course, is “15 Years of Weibo,” reflecting on the platform’s evolution since its launch in 2009 and its role in China’s competitive social media ecosystem today. We’ll explore the most popular influencers on Weibo, go deeper into Weibo diplomacy aka ‘Weiplomacy’, and will feature a special contribution by an expert guest writer. More on that coming soon!

A shout-out to Miranda Barnes and Ruixin Zhang for helping select some of the topics for this newsletter, and a very special thanks to Wytse Koetse for filming and editing the What’s on Weibo Chapters video.

Stay tuned!

Warm greetings,

Manya Koetse

(@manyapan)

What’s New

Our picks | From ‘Chillax’ to ‘Digital Ibuprofen,’ this compilation of ten Chinese buzzwords and catchphrases by What’s on Weibo reflects social trends and the changing times in China in 2024.

What’s Trending

🏚️ Earthquake in Tibet

The devastating 7.1 magnitude earthquake that struck Shigatse’s Tingri County high on the Tibetan plateau on the morning of January 7th has already claimed the lives of at least 95 people and left over 130 injured. Approximately 6,900 people reside in the villages surrounding the earthquake’s epicenter. On Weibo, videos reveal the catastrophic impact of the earthquake, with entire neighborhoods reduced to rubble.

Shigatse City’s Deputy Mayor Liu Huazhong (刘华忠) appeared visibly emotional as he announced the latest death toll and shared that 14 townships have been severely affected by the disaster. At the time of writing, the government has activated the highest-level emergency response for disaster relief, with hundreds of rescue workers deployed to the affected areas to provide medical assistance, conduct search and rescue operations, and distribute emergency supplies.

🤒 Peak Flu Season

It’s peak flu season, and it’s evident in the various trending topics circulating on Chinese social media. As discussions grow about crowded hospitals, face masks, and flu medication, concerns about the rapidly rising rates of influenza viruses have also emerged. Currently, according to monitoring data from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, over 99% of flu cases in China are identified as the Influenza A virus subtype H1N1 (“甲流”).

There have also been reports of an increase in flu-like human metapneumovirus (HMPV, 人偏肺病毒) infections in northern China, particularly among children under the age of 14. On social media, Chinese experts are largely addressing these concerns by emphasizing that HMPV is not the same as Covid-19, is less common compared to influenza and mycoplasma infections, and that the recent rise in HMPV cases is not unusual but rather reflects the typical higher prevalence of respiratory viruses during winter.

🏓 Chinese Table Tennis Superstars Withdraw from World Rankings

There has been a lot of buzz about the world of table tennis recently. After a tumultuous 2024 in which Chinese table tennis players shone at the Paris Olympics, super popular table tennis stars Fan Zhendong (樊振东) and Chen Meng (陈梦) announced on Weibo (post 1, post 2) their withdrawal from the World Rankings (WR) due to new fines imposed by the International Table Tennis Federation (ITTF) for players not participating in tournaments.

Fan wrote that the Paris Olympics had left him “mentally exhausted” and that the new rules imposing fines for not participating in tournaments left him no other choice but to withdraw entirely. He also said he would not retire yet and quoted the Wicked line, “It’s time to try defying gravity 💚.” That post received more than 2.8 million (!) likes. Likewise, Chen also wrote about the impact of Olympic stress and that she still needs time to recover.

The withdrawal of these major table tennis icons—veteran athlete Ma Long (马龙) later also announced his withdrawal—has ignited discussions and criticism over WTT’s mandatory participation rule and whether it merely serves commercial interests instead of protecting athletes. Liu Guoliang (刘国梁), president of the Chinese Table Tennis Association (CTTA), said he would press World Table Tennis to revise its rules.

🏛️ Verdict in Handan Schoolboy Murder Case

A case in which a young boy from Feixiang County in Handan, Hebei, was murdered by three classmates shocked the nation in March 2024. The young boy, Wang Ziyao (王子耀), had suffered years of bullying before his three classmates, all 13 years old, killed and buried him. Wang had been missing for one day before his body was discovered buried in a greenhouse in a field near the home of one of the suspects. The case attracted major attention at the time, not just because of the cruel crime, but also due to its legal implications. Since an amendment to China’s Criminal Law in 2021, children between the ages of 12 and 14 can be held criminally responsible for extreme and cruel cases resulting in death or severe disability, if approved for prosecution by the Supreme People’s Procuratorate (SPP).

Now, the court verdict has been reported by Chinese media. Two of the male defendants were sentenced to life imprisonment, while the third defendant was not legally punished due to his minor role in the crime but was still placed under “special correctional education.” The verdict has triggered discussions on its implications and how it should now be clear to minors aged 12 and above, and their parents, that they cannot escape severe punishment for extreme crimes.

🎬 Li Mingde’s Livestream Permanently Banned

The young Chinese actor Li Mingde (李明德), also known as Marcus Li, has been the center of attention on Chinese social media recently due to the drama surrounding the production of the Chinese TV series The Triple Echo of Time (三人行). In a Weibo post published on the night of January 4, Li, a supporting actor in the series, accused co-star Ma Tianyu (马天宇), the male lead, of displaying diva behavior on set. He also complained about the harsh filming conditions, alleging that he was made to wait in freezing temperatures wearing nothing but a t-shirt.

The production team has since issued a statement denying Li’s claims and turned the tables, accusing Li of being unreasonable, negative, and frequently late or leaving early during filming. They also confirmed that they had officially terminated their collaboration with him.

Adding to the controversy, Li Mingde’s livestream channel was suddenly shut down on January 7, with Douyin permanently banning his account. The platform cited “deliberately stirring controversy to attract attention” as the reason for the ban, sparking widespread discussion online. Li, who has over 7.6 million followers on Weibo, continues to post updates at the time of writing. After Ma Tianyu suggested in a now-deleted post that Li might be suffering from a mental illness, Li refuted the claim and stated he plans to take legal action. It seems this drama is far from over.

What’s Noteworthy

Did you know that the final Guinness World Record of 2024 was set by Chinese e-commerce giant JD.com? Honestly, the record is so unusual that I initially struggled to understand what the achievement was: JD.com now holds the Guinness World Record for the world’s “largest object unveiled” in Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan, on December 29, 2024—a staggering 400.66 meters long.

Is it a rocket? A train? A cruise ship?

No, it’s actually a list of 173,583 authentic user comments—a 400-meter-long comment section reviewing the platform’s major home appliance products. JD.com, one of the leading players in China’s home goods and household appliances market, seems to have orchestrated this extravagant marketing stunt to emphasize its position as a trustworthy market leader with an alleged 98% satisfaction rate.

The 400+ meter list, via Digitaling.

As an online retailer, printing reviews and displaying them in an offline setting where virtually no one but Guinness World Records takes notice does seem wasteful. But here we are, talking about it—along with a trending hashtag (#24年最后一个吉尼斯纪录是京东的#), so I suppose the PR effort paid off.

What’s Popular

After the 2024 success of Her Story(好东西) directed by Shao Yihui (邵艺辉) YOLO (麻辣滚烫) by Jia Ling (贾玲), Like A Rolling Stone (出走的决心) by Yin Lichuan (尹丽川), we are now seeing another hit film by a female director, highlighting the growing prominence of female directors in Chinese cinema.

The hashtag for the new movie Little Me (小小的我) has received over a billion views on Weibo this week (#电影小小的我#), noting its popularity. The movie was directed by Yang Lina (杨荔钠), the female director also known for her film Song of Spring (妈妈), which tells the moving story of an 85-year-old mother caring for her 65-year-old daughter with Alzheimer’s disease.

Little Me again touches on profound themes as it tells the story of a young man suffering from cerebral palsy who nevertheless tries to find his own direction in life. The role is played by Jackson Yee (易烊千玺), the superstar with an enormous fanbase on social media. Although he is still known as the youngest member of the boyband TFboys, Yee has gone far beyond that and shows his talent and dedication as an actor in this film with a credible performance.

Although Jackson Yee’s standout performance in Little Me is praised across social media, some have also commented that the actor might be too good for the film. Qilu Evening News published a sharp movie review, noting that Yee’s performance creates a stark divide between his brilliance and the film’s otherwise mediocre quality. This disparity has led some viewers to comment that Little Me is “a dumpling made just for the vinegar” (“为了一碟醋包了一顿饺子”). Despite this criticism, the film is still scoring a 7.2 on the Douban platform, where it has been rated by over 164,000 people.

What’s Memorable

As we’re entering the second week of 2025, I’d still like to take this time to look back look back at 10 of the most popular stories on

What’s On Weibo of 2024 for this week’s archive lookback. From viral trends to shocking incidents, it was a tumultuous year with some moments that’ll be ingrained in China’s collective digital memory. 🧵👇

1️⃣🐱 When ‘Fat Cat’ Jumped into the Yangtze River | He invested all he had for a girl he’d met online. Then she broke up with him. The tragic story behind the suicide of a 21-year-old Chinese gamer nicknamed ‘Fat Cat’ (胖猫) became a major topic of discussion on Chinese social media in May of 2024, touching upon broader societal issues from unfair gender dynamics to businesses taking advantage of grieving internet users.

🔗

https://www.whatsonweibo.com/the-tragic-story-of-fat-cat-how-a-chinese-gamers-suicide-went-viral/

2️⃣✨ Chengdu Disney | How did a common park in Chengdu turn into a hotspot that got everyone talking? By mixing online trends with real-life fun, blending foreign styles with local charm, and adding humor and absurdity, Chengdu had the recipe for its very own ‘Chengdu Disney’ in 2024. Undeniably, the quirkiest trend of the year.

🔗

https://www.whatsonweibo.com/chengdu-disney-the-quirkiest-hotspot-in-china/

3️⃣💧 Nongfu and Nationalists | One of the most noteworthy online phenomena in China during 2024 was the big battle over bottled water after the death of Zong Qinghou (宗庆后), the founder and chairman of Wahaha Group (娃哈哈集团), the country’s largest beverage produce. What started as a support campaign for Wahaha morphed into a crusade against another major water brand, Nongfu Spring, led by online nationalists.

🔗

https://www.whatsonweibo.com/in-hot-water-the-nongfu-spring-controversy-explained/

4️⃣🔪 Beishan Park Stabbings | 2024 was, unfortunately, a year of many deadly mass attacks by individuals ‘taking revenge on society,’ from Zhuhai to Changde. One such incident that made headlines around the world was the June 10 stabbing at Beishan Park in Jilin, which left four American teachers injured, among others. While the story spread widely on X, it was initially kept under wraps on the Chinese internet. This article analyzes how the incident was reported, censored, and discussed on Weibo.

🔗

https://www.whatsonweibo.com/the-beishan-park-stabbings-how-the-story-unfolded-and-was-censored-on-weibo/

5️⃣🥇 Golden Olympics | The 2024 Paris Olympics were the talk of Chinese social media. Beyond the gold medal moments, there were plenty of happenings on the sidelines, at the venues, and on the award stage that went viral, sparking countless memes. From China’s cutest weightlifter to viral sensation Quan Hongchan, this top 10 list of meme-worthy moments was a favorite among readers.

🔗

Team China’s 10 Most Meme-Worthy Moments at the 2024 Paris Olympics

6️⃣🚗 Land Rover Woman | In 2024, ‘Land Rover Woman’ (路虎女) became the latest addition to the Chinese Lexicon of Viral Incidents. A female Land Rover driver sparked outrage among Chinese netizens with her entitled behavior, driving against traffic and reacting aggressively when confronted—even striking a Chinese veteran in the face. The incident highlighted widespread frustration with social class injustice, as many viewed it as reflecting existing power imbalances between the wealthy and the working-class.

🔗

https://www.whatsonweibo.com/weibo-watch-the-land-rover-woman-controversy-explained/

7️⃣🧮 Controversial Math Genius Jiang Ping | It’s rare for a math competition to become the focus of nationwide attention in China. But when 17-year-old vocational school student Jiang Ping made it to the top 12 of Alibaba’s Global Math Competition, competing against contestants from prestigious universities worldwide, her humble background and outstanding achievement sparked debates and triggered rumors. She was called China’s version of Good Will Hunting, but her math story had a disappointing ending.

🔗

https://www.whatsonweibo.com/chinas-controversial-math-genius-jiang-ping/

8️⃣🇺🇸 Trump’s Triumph |The assassination attempt on former US President (now President-elect) Trump at a Pennsylvania campaign event in July 2024 became a major topic on Chinese social media. Trump’s swift reaction and defiant gesture after the shooting not only sparked widespread discussions but also fueled the “Comrade Trump” meme machine.

🔗

https://www.whatsonweibo.com/a-triumph-for-comrade-trump-chinese-social-media-reactions-to-trump-rally-shooting/

9️⃣📚 Crusade against Smut | A recent crackdown on Chinese authors writing erotic web novels sparked increased online discussions about the Haitang Literature ‘Flower Market’ subculture, the challenges faced by prominent online smut writers, and the evolving regulations surrounding digital erotica in China. But how serious is the “crime” of writing explicit fiction in China today? Ruixin Zhang explored this topic in an insightful and widely-read article, with a sad update.

🔗

https://www.whatsonweibo.com/the-price-of-writing-smut-inside-chinas-crackdown-on-erotic-fiction/

🔟🚴♂️ Cycling to Kaifeng | The term ‘yè qí‘ (夜骑), meaning “night ride,” suddenly became a buzzword on Chinese social media in late fall of 2024, as large groups of students from various schools and universities in Zhengzhou started cycling en masse to the neighboring city of Kaifeng on shared bicycles in the middle of the night. From city marketing to the spirit of China’s new generation, there are many themes behind their nightly cycling caravan, explained in this article, which also became one of the best-read pieces on What’s on Weibo this year:

🔗

https://www.whatsonweibo.com/the-cycling-to-kaifeng-trend-how-it-started-how-its-going/

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Popular Reads

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music10 months ago

China Music10 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Insight11 months ago

China Insight11 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Digital8 months ago

China Digital8 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI