Newsletter

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

The future is here, but it looks different than we expected. This Weibo Watch covers driverless taxis and other noteworthy, popular topics.

Published

8 months agoon

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #33

This week’s newsletter:

◼︎ 1. Editor’s Note – The future is here

◼︎ 2. What’s New and Noteworthy – A closer look at the featured stories

◼︎ 3. What’s Trending – Hot highlights

◼︎ 4. What’s Remarkable – A panicked mum goes to extremes

◼︎ 6. What’s Popular – The passing of Cheng Peipei

◼︎ 7. What’s Memorable – Virtual news anchors

◼︎ 8. Weibo Word of the Week – Bye bye, Biden

Dear Reader,

The future is here, and it is all unfolding so much differently than we could have imagined.

Scrolling through Douyin and Weibo’s video feeds recently, there are hundreds of videos about China’s self-driving taxi revolution. The wonder and excitement over the unmanned cabs is not surprising – it is the biggest thing happening in China’s taxi industry since ride-hailing apps Didi, Kuaidi, and Uber first entered the Chinese market over a decade ago.

Luobo Kuaipao (萝卜快跑) by Baidu, called ‘Apollo Go’ in English, is the ‘robotaxi’ ride-hailing platform that is now generating the most attention online. The concept is simple: customers order the taxi via the app and enter their destination, it arrives at the meeting point, and via a panel on the side of the car, the customer inserts the last four digits of their phone number. The door then automatically opens, and they can get in the car, which will take them to where they want to go. The car is private, and the price is comparable to ride-sharing fees, but then cheaper.

There is an additional benefit: the cars are equipped with a “smart cockpit”, allowing passengers to start their journey by tapping the screen in front of them, selecting a podcast or their favorite music, controlling the air-conditioning, and watching the traffic while en route.

Currently, Luobo Kuaipao has some 500 robotaxis operating without safety drivers in Wuhan, now the world’s largest city for driverless taxis. Baidu plans to expand this fleet with an additional 1,000 robotaxis soon. Shanghai will also launch a public testing program for driverless taxi services by SAIC in the upcoming week.1

Across China, at least 16 cities are now testing self-driving vehicles, with at least 19 Chinese car manufacturers competing for global leadership. Nationwide, 20 provinces have already released policies and regulations for autonomous driving.23

In many bigger Chinese cities, smart autonomous vehicles are already part of daily life. For years now, autonomous cleaning cars have been a common sight in popular tourist spots. I remember seeing a cute little car working hard to clean the area around the Terracotta Warrior museum in Xi’an in 2019. There are also self-driving tourist shuttles, driverless trucks operating between Beijing and Tianjin, and AI-driven service carts that precisely know where crowds gather during lunch breaks, stop when people wave, and process mobile payments for hamburgers or chicken salads on the spot.

So far, so ‘futuristic.’

But it’s not all roses. Besides the many enthusiastic videos taken by Chinese riders posting their experiences of taking an unmanned, self-driving taxi for the very first time, the emergence and rising popularity of robotaxis is also leading to worries, complaints, and aggravation.

A commonly heard objection to the unmanned taxis is that they are taking away jobs in the taxi industry. Perhaps even more so than when ChatGPT first emerged, the question of AI replacing people rather than serving them is frequently popping up, with taxi drivers fearing they’ll lose their jobs as robotaxis spread throughout China. These worries can still be countered by the numbers. After all, Wuhan has more than 100,000 registered ride-hailing cars, and Luobo Kuaipao holds just around 0.40% of the market – an insignificant number. 4 But with the rise of the industry, including its competitive prices, that number is bound to change.

Another far more unexpected concern about the rise of China’s robotaxis is that they’re causing chaos in the streets by being ‘too polite.’ These autonomous taxis are trained to follow the traffic rules and act civilized in traffic – something that seems out of place in some areas, where not following the rules almost seems like a rule.

By staying in the right lane, stopping for red lights, and giving priority to other cars, pedestrians, and animals, Chinese robotaxis are causing road congestion and sometimes accidents. They often struggle with complex traffic situations; for example, a viral video showed two Luobo Kuaipao cars waiting for each other to move, holding up traffic. In Wuhan, where drivers are known for their aggressive driving style, these autonomous cars face additional challenges. They strictly follow traffic laws and are not accustomed to pushing their way into traffic, which can lead to long waits for simple turns or merges, causing delays for other drivers.

This behavior has earned them the nickname ‘Sháo Luóbo’ (勺萝卜, “silly radish”), suggesting they are sluggish, or dumb. Although Luobo Kuaipao translates to ‘Radish Runs Fast’ or ‘Carrot Run,’ implying speed and efficiency, the reality is quite different.

Also unexpected is how ‘driverless’ is not what you might have thought it is; because every car still has a “safety operator” who is remotely monitoring it from another location. One person can monitor 10 cars or even more, but they’re allegedly penalized if they close their eyes for more than three seconds.5 Videos and pictures from these robotaxi headquarters sometimes look like old-fashioned game halls or internet cafes.

Complaints about Luobo Kuaipao not being as modern as people hoped and not being as assertive as they thought ultimately boil down to a clash of cultures. Luobo Kuaipao is made in China, but it’s not programmed with the personality and ways of a Wuhan taxi driver. In the end, Wuhan drivers will need to learn from Luobo Kuaipao, and Luobo Kuaipao will need to learn from Wuhan traffic. One side will learn to become more ‘polite,’ while the other will need to add some ‘aggression’ in order to mix in with traffic.

As ‘silly’ as Luobo Kuaipao may seem now, let’s not forget that everything starts small – we all began in diapers. Nothing significant ever came without humble beginnings. The future is here, but what we consider truly ‘futuristic’ will perhaps always be a vision for the days to come.

Miranda Barnes and Ruixin Zhang have contributed to the compilation and interpretation of some topics featured in this week’s newsletter. As always, if you have any observations or ideas you’d like to share, please don’t hesitate to reach out to me.

Best,

Manya Koetse

(@manyapan)

References:

1 Wu Qingqing 吴青青. 2024. “The Luobo Kuaipao Versus Tesla War”[萝卜快跑,与特斯拉终有一战].” Auto Business Review (汽车商业评论), July 18 https://inabr.com/news/19693 [Accessed July 22, 2024].

2 Bradsher, Keith. 2014. “China Is Testing More Driverless Cars Than Any Other Country.” New York Times, June 14 https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/13/business/china-driverless-cars.html [Accessed July 22, 2024].

3 Qi Xu 齐旭. 2024. “Which City is China’s First City for Autonomous Driving? [谁是中国自动驾驶“第一城”?]” China Electronics News 中国电子报, July 16 https://new.qq.com/rain/a/20240716A00W2N00?suid=&media_id= [Accessed July 22, 2024].

4 Wu Qingqing 吴青青. “The Luobo Kuaipao Versus Tesla War.”

5 Jones, Phil. 2014. “Behind Driverless Cars – The Safety Operators Who Can’t Close Their Eyes[无人驾驶车背后,是无法闭眼的安全员].” The Paper, July 19 https://m.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_28124126 [Accessed July 22, 2024].

What’s New

“As smooth as a flying bullet” | The assassination attempt on former US President Trump at a Pennsylvania campaign event also became a major topic on Chinese social media, where Trump’s swift reaction and defiant gesture after the shooting have not only sparked discussions but also fueled the “Comrade Trump” meme machine.

Park with a view | “The ‘sea in Ditan Park’ is a perfect example of how Xiaohongshu netizens use their imagination to change the world,” a recent viral post on Weibo said. This seaview spot in the Beijing public park has become a new ‘check-in spot’ among Chinese Xiaohongshu users and influencers.

From Hollywood to Beijing | For the Dutch national broadcaster’s summer series ‘From Hollywood to Bollywood,’ I spoke about the Chinese blockbuster Battle at Lake Changjin (2021) this week. This spectacular war film depicts the story of Chinese troops during the massive Battle of the Chosin Reservoir in the Korean War, where they encircled and pushed back American forces. The film is an impressive visual spectacle, but it’s a landmark movie in other aspects as well. Under the leadership of President Xi Jinping, China is striving to become a global powerhouse in the film industry. At the same time, this film also helped shape new narratives of the Korean War that foster patriotism. Dutch readers can listen to or watch the entire conversation via the link. If you’re interested in learning more about this topic but not that good at understanding Dutch—nobody’s blaming you—check out this article on WoW from our archive.

What’s Trending

JULY 11

🛢️🍳 Cooking Oil Scandal | A major news topic that’s been fermenting over the past month is the revelation that some cooking oil transport trucks in China are also being used for transporting industrial oil. The issue went trending after a publication by Beijing News authored by investigative journalist Han Futao (韩福涛) on July 2, which detailed how the same tanks were used for transporting both edible oils like soybean oil and chemical oils like kerosene without any cleaning process. The food safety scandal sparked outrage online and led to people meticulously tracking the whereabouts of oil tankers and how they operate, while various tanker companies came forward to provide clarity on their procedures. The incident has raised significant awareness about the potential misuse of tankers and intensified concerns about food safety in China.

JULY 15

🚗 Trump Photo Copyrights | After the Trump rally shooting went viral across Chinese media, another trending hashtag emerged regarding the copyright of the iconic ‘raised fist photo,’ shot by award-winning photographer Evan Vucci. Chinese online sources attributed the photo’s rights to the photo agency “Visual China” (视觉中国), allegedly charging 2100 yuan ($288) per use on social media, with threats of lawsuits for unauthorized use. This sparked debates over copyright ownership, as Evan Vucci was not mentioned. In the past, the same company triggered controversy for claiming copyright for an image of the Chinese national flag. They were also sued by a Chinese photographer for claiming ownership of 173 of his photos. Visual China later clarified that they, as a partner of AP, only have distribution rights but do not own the Trump photo.

JULY 16

🌧️ Floods | Thousands of households across China have been affected by floods recently, from Sichuan to Hunan, from Henan to Shaanxi. The city of Xiangyang in Hubei is one such affected area, which experienced its strongest rainfall since the start of the flood season. Some areas nearby broke single day rainfall records, with cars in the streets being swept away by the water. In Henan, floods forced over 100,000 people to evacuate their homes, according to state media. The floods have been catastrophic, especially for farmers, leaving widespread devastation.

JULY 19

🏥 Wenzhou Doctor Killed | A vicious attack on a doctor at the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University has gone viral this week, sending shockwaves across Chinese social media. The incident occurred on the afternoon of July 19, when a man suddenly attacked and stabbed Dr. Li Sheng (李晟), who was on duty in the hospital’s cardiology department. The attacker subsequently jumped off the building. Despite extensive rescue efforts, Li succumbed to his injuries that night. The incident has sparked outrage, particularly in light of several recent stabbing incidents and the ongoing issue of patient-doctor violence, leading many netizens to call for improved security measures in hospitals. Tributes to Dr. Li Sheng online describe him as a man fully dedicated to his work and patients. China’s National Health Commission condemned the attack, stating there is zero tolerance for any form of violence against medical personnel.

JULY 20

🌉 Collapsed Bridge | After heavy rain and flash floods, a highway bridge that had been in use for less than six years in Shangluo, Shaanxi Province, collapsed on July 19th, causing 25 vehicles to fall into the river. While rescue efforts were still underway, the incident has resulted in 12 known deaths and 31 missing. The past weekend, two missing vehicles were found downstream, 4 kilometers from the collapse site. More than 700 professionals from various emergency services, along with over 1,500 local officials and residents, have been mobilized for search and rescue operations.

JULY 17

🔥🚒 Shopping Mall Fire | Videos of a terrible fire at the 14-story Jiuding Department Store in Zigong, Sichuan, spread on Chinese social media on Wednesday night. Initially, the death toll stood at 8, but it later emerged that at least 16 people lost their lives in the flames despite extensive rescue efforts by firefighters. Thirty-nine people were hospitalized. The fire, now known as the “7·17 major fire accident” (“7·17重大火灾事故”), is suspected to be linked to ongoing construction work.

JULY 21

🏅🧳 Olympic Suitcase Fever | Just a few days before the start of the Olympic Games in Paris, and the Olympic fever is noticeable on Chinese social media. Chinese state media have issued phone wallpaper featuring Olympic athletes. However, what recently attracted the most attention are the suitcases used by Chinese athletes traveling to Paris. These suitcases, called “Ying Yong” (英俑), were designed exclusively for the Chinese sports delegation by a company in Hangzhou. The design is themed around the Terracotta Warriors, using red and black and featuring other details inspired by the Terracotta Army.

JULY 22

🏫 Professor Mi | A story about renowned Chinese professor Wang Guiyan (王贵元) has been blowing up on Chinese social media after he was accused of sexual misconduct by a former female doctoral student. She made these allegations through an online video against the professor, who also served as the Party Secretary and Vice Dean of the School of Liberal Arts at Renmin University of China. On July 22, the university responded to the allegations and stated that their investigations found them to be true. As a result, Wang has been expelled from the Party, his professorship has been revoked, his qualification as a graduate supervisor has been canceled, he has been removed from his teaching position at Renmin University, and his employment has been terminated.🔚

What’s Noteworthy

A mother who lost her child while shopping in a mall in Shiyan, Hubei, went to extreme measures to get her child back as soon as possible. On July 19, the panicked woman triggered the mall alarm by smashing the displays at a jewelry store with a fire extinguisher. This caused the mall to shut all its doors and prompted a police squad to arrive within minutes. A viral video of the incident showed the mother shouting for help as she broke glass displays. The child was soon located.

In the past, there have been various stories about children being kidnapped and having their appearances changed quickly, making it much more challenging to find them. One such story from 2018 showed the speed at which human traffickers work: a 5-year-old girl went missing from a local playground at 14:41, and it later became clear that the little girl, taken away in a minivan with a middle-aged woman and another child, departed her city by train just fifteen minutes later. She got off at a station some 60 miles away with changed clothes and a shaved head (read here).

Although the mother may have thought she did the right thing by smashing the displays to get help to locate her child as soon as possible, she is also receiving a lot of criticism online. Commenters argue that the woman should have never lost sight of her child in the first place, let alone vandalized mall property. The jewelry store also had nothing to do with the child going missing. The local police stated that the woman’s actions would be handled according to public security regulations, so she can expect to pay a fine and compensation to the store.

Meanwhile, there are also people who sympathize with the mother, as they don’t want to imagine what could have happened to the child if standard, slower procedures were followed. However, state media outlets warn others not to take the woman as an example.

What’s Popular

She was known as the heroine and villain of Wuxia movies, the queen of the swords, and a martial arts diva. Hong Kong actress Cheng Pei-pei (郑佩佩) trended all day on Chinese social media after news broke that she had died at the age of 78.

The Shanghai-born Cheng had a background in ballet and modern dance—skills she incorporated into the fight choreographies of the martial arts films she made for the Shaw Brothers in the 1960s and 70s. She later moved to the United States. Cheng gained international fame when she starred as Jade Fox in Ang Lee’s “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” in 2000. Cheng suffered from Corticobasal degeneration (CBD), which shares some similarities with Parkinson’s disease.

On social media, Cheng is remembered not only by other actors and celebrities but also by many regular netizens who see her passing as a major loss to the Chinese film industry. (To read more about the Shaw Brothers & Chinese cinema, check our article here.)

What’s Memorable

For this pick from the archive, and in the context of the future being here, we revisit a 2023 article about Chinese state media introducing a virtual news anchor. While the first virtual presenter was introduced in 2019, People’s Daily introduced Ren Xiaorong (任小融) as a virtual presenter/news anchor in 2023. Although virtual news presenters are not yet the norm, this is a trend that is still developing. For example, this week, China’s Military News Agency also launched their virtual anchor to improve communication efficiency.

Weibo Word of the Week

Bye Bye Biden | Our Weibo phrase of the week is Bye Bye Biden (bài bài Bàidēng 拜拜拜登).

As news of Biden dropping out of the presidential race went viral on Weibo early Monday local time, it’s time to reflect on some of the popular nicknames and phrases given to US President Joe Biden on Chinese social media.

🔹 Biden in Chinese: Bàidēng 拜登

Biden in Chinese is generally written pronounced and written as Bàidēng 拜登. Although the character 拜 (bài) means “to pay respect, to worship” and 登 (dēng) means “to ascend, to climb,” they’re used here primarily for their phonetic similarity. The characters chosen are neutral to avoid any negative implications in the official translation of Biden’s name.

Why are non-Chinese names translated into Chinese at all? With English and Chinese being vastly different languages with entirely different phonetics and scripts, most Chinese people find it difficult to pronounce a foreign name written in English. Writing foreign names in Chinese not only standardizes them but also makes pronunciation and memorization easier for Chinese speakers.

🔹 Bye Biden: Bài Bài Bàidēng 拜拜拜登

Because Biden is Bàidēng, and the Chinese for ‘bye bye’ is written as bài bài 拜拜, some netizens quickly created the wordplay “bài bài Bàidēng” 拜拜拜登 (“bye bye Biden”) upon hearing that Biden would not seek reelection. Try saying it out loud—it almost sounds like you’re stammering.

🔹 Old Joe: Lǎo Dēng Dēng 老登登

Another common farewell greeting to Biden seen online is “bài bài lǎo dēng dēng” 拜拜老登登, which sounds cute due to the repetition of sounds.

“Old Biden” or “lǎo dēng dēng” 老登登 is a common online nickname for Biden in Chinese. The reduplication of the 登 (dēng) makes it sound playful and affectionate, while the “old” prefix is commonly used when referring to someone older. It’s similar to calling someone “Old Joe” in English.

🔹 Biden Variations: 拜灯, 白等, 败蹬

Let’s look at some other ways Biden is nicknamed online:

Besides the official way of writing Biden with the 拜登 Bàidēng characters, there are also other variations:

拜灯: bài dēng

白等: bái děng

败蹬: bài dèng

These alternative ways of writing Biden’s name are not neutral. Although the first variation is not necessarily negative (using the formal Biden 拜 bài character but with ‘Light’ 灯 dēng instead of the other 登 ‘dēng’), the other two variations are usually used in more negative contexts.

In 白等 (bái děng), the first character 白 (bái) means “white,” which can evoke associations with old age due to white hair (白发). The character 等 (děng) means “to wait,” and the combination can imply being old and sluggish.

败蹬 (bài dèng) is typically used by netizens to reflect negative sentiments towards the American president. The characters separately mean 败 (bài): “to be defeated,” “to fail,” and 蹬 (dèng): “to step on,” “to kick.” This would never be used by official media and is also often used by netizens to circumvent censorship around a Biden-related topic.

🔹 Revive the Country Biden: Bài Zhènhuá 拜振华

Then there is 拜振华 Bài Zhènhuá: revive the country Biden

In recent years, Biden has come to be referred to with the Chinese nickname “Revive the Country Biden,” also translatable as ‘Thriving China Biden’. This nickname has circulated online since 2020 and matches one previously given to former President Trump, namely “Build the Country Trump” (Chuān Jiànguó 川建国).

The idea behind these humorous monikers is that both Trump and Biden are seen as benefitting China by doing a poor job in running the United States and dealing with China.

🔹 Sleepy King: Shuì wáng 睡王

Shuì wáng 睡王, Sleepy King, is another common nickname, similar to the English “Sleepy Joe.” During and after the 2020 American presidential elections, there were numerous discussions on Chinese social media about ‘Trump versus Biden.’ Many saw it as a contest between the ‘King of Knowing’ (懂王) and the ‘Sleepy King’ (睡王).

These nicknames were attributed to Trump, who frequently boasted about his unparalleled understanding of various matters, and Biden, who gained notoriety for being older and tired. Viral videos, some manipulated, showed him nodding off or seemingly disoriented. The name ‘Sleepy King’ then stuck.

🔹 Grandpa Biden: Bài Yéyé 拜爷爷

Throughout the years, Biden has also been nicknamed Bài yéyé 拜爷爷, “Grandpa Biden.” This is usually more affectionate, though it emphasizes his age—Trump is not much younger than Biden and is not nicknamed ‘Grandpa Trump.’

Another similar nickname is lǎo bái 老白, “Old White,” referring to Biden’s age and white hair. 白 (bái, white) can also be a surname in Chinese. This nickname makes it seem like Biden is an old, familiar friend.

On Weibo, many speculate that American Vice President Kamala Harris will be the new candidate for the Democrats, especially since she’s been endorsed by Biden. Many have little confidence that she can compete against Trump. Her Chinese name is Kǎmǎlā Hālǐsī 卡玛拉·哈里斯, commonly referred to as ‘Harris’ (Hālǐsī).

In light of the latest developments, some netizens jokingly write: “Bye bye Biden, Ha ha ha, Harris.” (Bài bài, Bàidēng. Hā hā hā, Hālǐsī 拜拜,拜登。 哈哈哈,哈里斯). With a new Democratic candidate entering the presidential race, we can expect a fresh batch of creative nicknames to join the mix on Chinese social media.

Want to read more? Also read: Why Trump has Two Different Names in Chinese.

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

Newsletter

Weibo Watch: The Great Squat vs Sitting Toilet Debate in China🧻

This week, the Catch-22 of sitting versus squat toilets sparked heated discussion on Weibo after a Beijing News article exposed the messy reality of sitting toilets in Beijing malls.

Published

2 days agoon

March 23, 2025

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #50

Dear Reader,

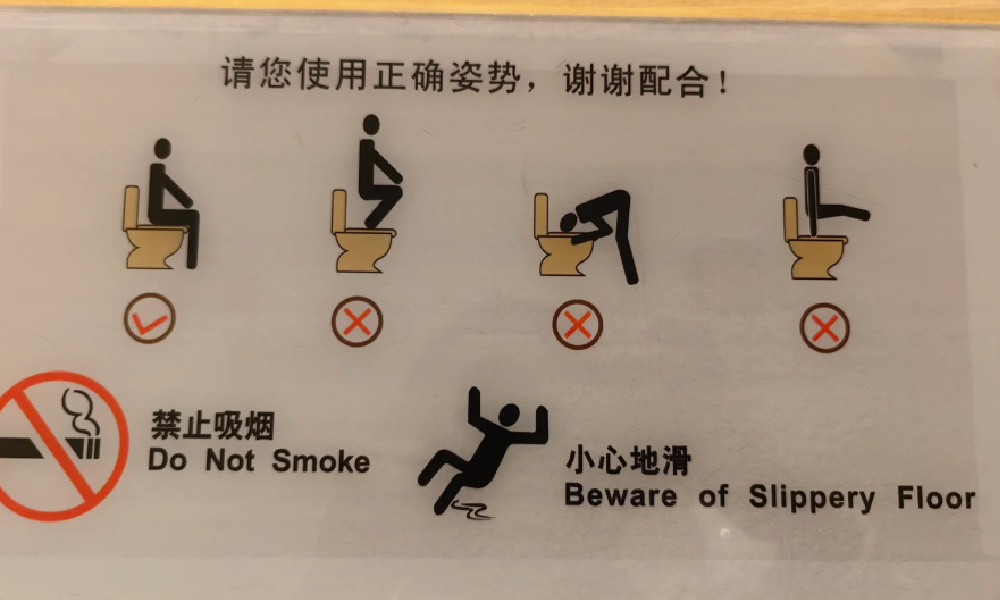

Shoe prints on top of the toilet seat are never a pretty sight. To prevent people from squatting over Western-style sitting toilets, there are some places that will place stickers above the toilet, reminding people that standing on the seat is strictly forbidden.

For years, this problem has sparked debate. Initially, these discussions would mostly take place outside of China, in places with a large number of Chinese tourists. In Switzerland, for example, the famous Rigi Railways caused controversy for introducing separate trains with special signs explaining to tourists, especially from China, how (not) to use the toilet.

Squat toilets are common across public areas in China, especially in rural regions, for a mix of historical, cultural, and practical reasons. There is also a long-held belief — backed by studies (like here or here) — that the squatting position is healthier for bowel movements (for more about the history of squat toilets in China, see Sixth Tone’s insightful article here).

Public squatting toilets in Beijing, images via Xiaohongshu.

Without access to the ground-level squat toilets they are used to — and feel more comfortable with — some people will climb on top of sitting toilets to use them in the way they’re accustomed to, seeing squatting as the more natural and hygienic method.

Not only does this make the toilet seat all messy and muddy, it is also quite a dangerous stunt to pull, can break the toilet, and lead to pee and poo going into all kinds of unintended directions. Quite shitty.

Squatting on toilets makes the seat dirty and can even break the toilet.

Along with the rapid modernization of Chinese public facilities and the country’s “Toilet Revolution” over the past decade, sitting toilets have become more common in urban areas, and thus the sitting-toilet-used-as-squat-toilet problem is increasingly becoming topic of public debate within China.

The Toilet Committee and Preference for Sitting Toilets

Is China slowly shifting to sitting toilets? Especially in modern malls in cities like Beijing, or even at airports, you see an increasing number of Western-style sitting toilets (坐厕) rather than squatting toilets (蹲厕).

This shift is due to several factors:

🚽📌 First, one major reason for the rise in sitting toilets in Chinese public places is to accommodate (foreign) tourists.

In 2015, China Daily reported that one of the most common complaints among international visitors was the poor condition of public toilets — a serious issue considering tourists are estimated to use public restrooms over 27 billion times per year.

That same year, China’s so-called “Toilet Revolution” (厕所革命) began gaining momentum. While not a centralized campaign, it marked a nationwide push to upgrade toilets across the country and improve sanitation systems to make them cleaner, safer, and more modern.

This movement was largely led by the tourism sector, with the needs of both domestic and international travelers in mind. These efforts, and the buzzword “Toilet Revolution,” especially gained attention when Xi Jinping publicly endorsed the campaign and connected it to promoting civilized tourism.

In that sense, China’s toilet revolution is also a “tourism toilet revolution” (旅游厕所革命), part of improving not just hygiene, but the national image presented to the world (Cheng et al. 2018; Li 2015).

🚽📌 Second, the growing number of sitting toilets in malls and other (semi)public spaces in Beijing relates to the idea that Western-style toilets are more sanitary.

Although various studies comparing the benefits of squatting and sitting toilets show mixed outcomes, sitting toilets — especially in shared restrooms — are generally considered more hygienic as they release fewer airborne germs after flushing and reduce the risk of infection (Ali 2022).

There are additional reasons why sitting toilets are favored in new toilet designs. According to Liang Ji (梁骥), vice-secretary of the Toilet Committee of the China Urban Environmental Sanitation Association (中国城市环境卫生协会厕所专业委员会), sitting toilets are also increasingly being introduced in public spaces due to practical concerns.

🚽📌 Squatting is not always easy, and can pose a safety risk, particularly for the elderly, pregnant women, and people with disabilities.

🚽📌 Then there are economic reasons: building squat toilets in malls (or elsewhere) requires a deeper floor design due to the sunken space needed below the fixture, which increases both construction time and cost.

🚽📌 Liang also points to an aesthetic factor: sitting toilets simply look more “high-end” and are easier to clean, which is why many consumer-oriented spaces prefer to install Western-style toilets.

So although there are plenty of reasons why sitting toilets are becoming a norm in newly built public spaces and trendy malls, they also lead to footprints on toilet seats — and all the problems that come with it.

The Catch 22 of Sitting vs Squad Toilets

This week, the issue became a trending topic on Weibo after Beijing News published an investigative report on it. The report suggested that most shopping malls in Beijing now have restrooms with sitting toilets, which should, in theory, be cleaner than the squat toilets of the past — but in reality, they’re often dirtier because people stand on them. This issue is more common in women’s restrooms, as men’s restrooms typically include urinals.

In researching the issue, a reporter visited several Beijing malls. In one women’s restroom, the reporter observed 23 people entering within five minutes. Although the restroom had only three squat toilets versus seven sitting ones, around 70% of the users opted for the squat toilets.

Upon inspection, most of the seven sitting toilets were dirty — despite being equipped with disposable seat covers — showing clear signs of urine stains and footprints. They found that sitting toilets being used as squat toilets is extremely common.

It’s a bit of a Catch-22. People generally prefer clean toilets, and there’s also a widespread preference for squat toilets. This leads to sitting toilets being used as squat toilets, which makes them dirty — reinforcing the preference for squat toilets, since the sitting toilets, though meant to be cleaner, end up dirtier.

In interviews with 20 women, nearly 80% said they either hover in a squat or directly squat on the toilet seat. One woman said, “I won’t sit unless I absolutely have to.” While some of those quoted in the article said that sitting toilets are more comfortable, especially for elderly people, they are still not preferred when the seats are not clean.

In the Beijing News article, the Toilet Committee’s Liang Ji suggested that while a balanced ratio of squat and sitting toilets is necessary, a gradual shift toward sitting toilets is likely the future for public restrooms in China.

How NOT to use the sitting toilet. Sign photographed by Xiaohongshu user @FREAK.00.com.

Liang also highlighted the importance of correct toilet use and the need to consider public habits in toilet design.

In Squatting We Trust

On Chinese social media, however, the majority of commenters support squatting toilets. One popular comment said:

💬 “Please make all public toilets squat toilets, with just one sitting toilet reserved for people with disabilities.”

Squatting toilets in a public toilet in a Beijing hutong area, image by Xiaohongshu user @00后饭桶.

The preference for squatting, however, doesn’t always come down to bowel movements or tradition. Many cite a lack of trust in how others use public toilets:

💬 “When it comes to things for public use, it’s best to reduce touching them directly. Honestly, I don’t trust other people…”

💬 “Squatting is the most hygienic. At least I don’t have to worry about touching something others touched with their skin.”

💬 “I hate it when all the toilets in the women’s restroom at the mall are sitting toilets. I’m almost mastering the art of doing the martial-arts squat (蹲马步).”

Others view the gradual shift toward sitting toilets as a result of Westernization:

💬 “Sitting toilets are a product of widespread ‘Westernization’ back in the day — the further south you go, the worse it gets.”

But some come to the defense of sitting toilets:

💬 “Are there really still people who think squat toilets are cleaner? The chances of stepping in poop with squat toilets are way higher than with sitting ones. Sitting toilet seats can be wiped with disinfectant or covered with paper. Some people only care about keeping themselves ‘clean’ without thinking about whether the next person might end up stepping in their mess.”

💬 One reply bluntly said: “I don’t use sitting toilets. If that’s all there is, I’ll just squat on top of it. Not even gonna bother wiping it.”

It’s clear this debate is far from over, and the issue of people standing on toilet seats isn’t going away anytime soon. As China’s toilet revolution continues, various Toilet Committees across the country may need to rethink their strategies — especially if they continue leaning toward installing more sitting toilets in public spaces.

As always, Taobao has a solution. For just 50 RMB (~$6.70), you can order an anti-slip sitting-to-squatting toilet aid through the popular e-commerce platform.

The Taobao solution.

For Chinese malls, offering these might be cheaper than dealing with broken toilets and the never-ending battle against footprints on toilet seats…

Best,

Manya

(@manyapan)

References:

Ali, Wajid, Dong-zi An, Ya-fei Yang, Bei-bei Cui, Jia-xin Ma, Hao Zhu, Ming Li, Xiao-Jun Ai, and Cheng Yan. 2022. “Comparing Bioaerosol Emission after Flushing in Squat and Bidet Toilets: Quantitative Microbial Risk Assessment for Defecation and Hand Washing Postures.” Building and Environment 221: 109284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109284.

Bhattacharya, Sudip, Vijay Kumar Chattu, and Amarjeet Singh. 2019. “Health Promotion and Prevention of Bowel Disorders Through Toilet Designs: A Myth or Reality?” Journal of Education and Health Promotion 8 (40). https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_198_18.

Cao, Jingrui 曹晶瑞, and Tian Jiexiong 田杰雄. 2025. “城市微调查|商场女卫生间,坐厕为何频频变“蹲坑”? [In Shopping Mall Women’s Restrooms, Why Do Sitting Toilets Frequently Turn into ‘Squat Toilets’?]” Beijing News, March 20. https://weibo.com/ttarticle/p/show?id=2309405146044773302810. Accessed March 19, 2025.

Cheng, Shikun, Zifu Li, Sayed Mohammad Nazim Uddin, Heinz-Peter Mang, Xiaoqin Zhou, Jian Zhang, Lei Zheng, and Lingling Zhang. 2018. “Toilet Revolution in China.” Journal of Environmental Management 216: 347–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.09.043.

Dai, Wangyun. 2018. “Seats, Squats, and Leaves: A Brief History of Chinese Toilets.” Sixth Tone, January 13. https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1001550. Accessed March 22, 2025.

Li, Jinzao. 2015. “Toilet Revolution for Tourism Evolution.” China Daily, April 7. https://europe.chinadaily.com.cn/opinion/2015-04/07/content_20012249_2.htm. Accessed March 22, 2025.

China’s Online Discourse on the Russia-Ukraine War

In case you missed it in our earlier newsletter, we recently published the article “US-Russia Rapprochement and ‘Saint Zelensky’: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Shake-Up” as part of our What’s on Weibo Chapters. For more insights into how the war is discussed on Chinese social media, you can catch up here.

Stay tuned — we’re publishing another article on this topic later this week, exploring the unexpected connection between the Russia-Ukraine war and Chinese cosplayers.

What’s Trending

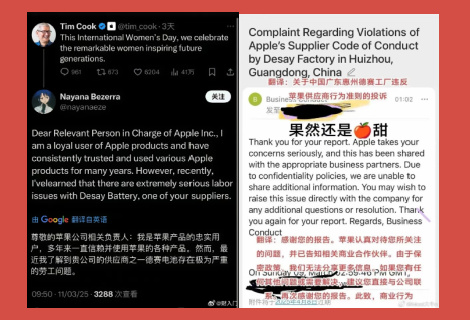

🍏 Chinese Netizens Turn to Tim Cook Over Factory’s Illegal Overtime

Netizens have recently started reaching out to Apple and its CEO Tim Cook in order to put pressure on a Chinese battery factory accused of violating labor laws. The controversy involves the Huizhou factory of Desay Battery (德赛电池), known for producing lithium batteries for the high-end smartphone market, including Apple and Samsung. The factory caught netizens’ attention after a worker exposed in a video that his superiors were deducting three days of wages because he worked an 8-hour shift instead of the company’s “mandatory 10-hour on-duty.” Compulsory overtime violates China’s labor laws.

In response, the worker and other netizens started to let Apple know about the situation through email and social media, trying to put pressure on the factory by highlighting its position in the Apple supply chain. By now, Desay Battery issued an official statement, admitting to “management oversights regarding employee rights protection” (“保障员工权益的管理上存在疏漏”) and promising to do better in safeguarding employee rights.

It’s an interesting story, and some commentators suggest that it shows that Chinese workers can effectively expose labor violations by reporting them to Western suppliers or EU regulators. But opinions vary. Others are less optimistic about the effectiveness, arguing that companies like Apple would be quick to drop suppliers over product quality issues but more willing to turn a blind eye to labor violations—since cheap labor remains a key competitive advantage in Chinese manufacturing.

💸 From Patriotic Influencer to Tax Evader: Sima Nan Fined More Than Nine Million Yuan

China’s well-known nationalist blogger Sima Nan (司马南) became a trending topic on Friday after being hit with a 9 million RMB ($1.2 million) fine for tax evasion. According to state media, from 2019 to 2023, he underpaid millions of yuan in personal income tax and other taxes by concealing income and submitting false declarations.

Sima responded to media, saying he fully admits guilt. At the same time he’s also blaming the multi-channel network that allegedly was in charge of paying taxes on his behalf at the time.

📌 Noteworthy: Sima Nan promised that- if he’ll still be allowed to have his social media presence – he would in detail explain how he ended up becoming a tax evader. This is kind of funny, because it shows just how good he is in what he does, turning his PR crisis into an opportunity for clicks and views 📈 (yes we do want to know how he went from patriotic influencer to becoming a multi-million tax dodger).

📌Public reaction: The most recurring comments I’ve seen on Weibo is that people are amazed at his high income. They note the hypocrisy of a nationalist, patriotic influencer who’s always preaching truth & justice evading taxes himself, and also conclude that being a nationalist is truly a money-making business🤑🇨🇳

💔 Tragedy at Hubei University: Zhang Yuzhen’s Disappearance and Aftermath

The disappearance of 19-year-old Chinese student Zhang Yuzhen (张钰臻) has captured nationwide attention this week. Zhang did not return after leaving her campus at Hubei University around 5 p.m. on March 15. Her phone remained traceable until 5:54 p.m., about one kilometer from campus. The case became a hot topic as millions of netizens turned into online sleuths, searching for clues that might lead to Zhang’s whereabouts.

On the afternoon of March 20, it was reported that Zhang’s personal items — including her keys and glasses — were discovered by a passerby next to a lake near the university. Police then began searching the lake. By that evening, her remains were found. The case is still under investigation.

There has been some online criticism regarding how the university handled Zhang’s disappearance. Although she was last seen on March 15, it wasn’t until March 18 that her parents were notified by a school counselor. They then reported her missing to the police, after which the school began cooperating with the investigation.

Now, there is also much discussion surrounding the behavior of Zhang’s mother, who has been publicly expressing her grief and anger on Douyin. After learning of her daughter’s death, she became emotionally distraught — screaming, crying, and demanding answers. She seemingly caused some public disturbance when she was prevented from immediately seeing her daughter’s remains, and was also not allowed to leave her hotel (perhaps due to concerns over her emotional state, though details remain unclear at this time). While some online voices have criticized her behavior, many are calling for empathy, arguing that any mother who has just lost her child would be desperate and distraught.

What’s Noteworthy

“The world is so big, I want to go out and see it” (Shìjiè nàme dà, wǒ xiǎng qù kànkan “世界那么大,我想去看看”).

This ten-character sentence became part of China’s collective social media memory after a teacher’s resignation note went viral in 2015. Now, a decade later, the phrase has gone viral once again.

In April 2015, the phrase caused a huge buzz on China’s social media when the female teacher Gu Shaoqiang (顾少强) at Zhengzhou’s Henan Experimental High School resigned from her job. Working as a psychology teacher for 11 years, she gave a class in which she made students write a letter to their future self. The exercise made her realize that she, too, wanted more from life. Despite having little savings, she submitted a simple resignation note that read: “The world is so big, I want to go out and see it.”

The resignation letter was approved, and she posted it to social media.

The letter resonated with millions of Chinese who felt they also wanted to do something different with their life, like go and travel, see the world, and escape the pressures and routines of their daily life. The phrase became so popular that it was adapted in all kinds of ways and manners, by meme creators, in books, by brands, and even by Xi Jinping, who said: “China’s market is so big, we welcome everyone to come and see it” (“中国市场这么大,欢迎大家都来看看”).

This week, Lěngshān Record (冷杉Record), the Wechat account under Chinese media outlet Phoenix Weekly (凤凰周刊), revisited the phrase and published a short documentary about Gu’s life after the resignation and the hype surrounding it.

An earlier news article about Gu’s life post-resignation already disclosed that Gu, despite receiving many sponsorship deals, never actually extensively traveled the world. In the short documentary, Gu explains that she chose to “return home after seeing the world.” By this, she doesn’t mean traveling extensively abroad, but rather gaining life experience in a broader sense. While she did travel, it was within China, including in Tibet and Qinghai.

What truly changed was her life path. She left Zhengzhou and relocated to Chengdu to be near Yu Fu (于夫), a man she had met just weeks earlier by chance during a trip to Yunnan. Six months after the resignation letter, she married him. Together, they ended up opening a hostel near Chengdu, married, and had a daughter.

Gu, now 45 years old, has been back in her hometown of Zhengzhou for the past years, caring for her aging mother and 9-year-old daughter. She is living separately from her husband, who manages their business in Chengdu. She also runs her own livestreaming and online parenting consultancy business.

Although the woman who wanted to “see the world” ended up back home, she has zero regrets about what she did, suggesting her courage to step out of the life she found limiting ultimately transformed her in a meaningful way.

On Chinese social media, the topic went trending on March 19. Most people cannot believe it’s already been ten years since the sentence went trending (“What? How could time fly like that?”). Others, however, wonder about the hopes and dreams behind the original message—and how it all turned out.

💬 “Seeing the world? She just escaped her old life, got married, and had a baby. How is that ‘seeing the world’?” one commenter wondered (@-NANA酱- ).

💬 “The world is so big—what did she end up seeing?” others questioned. “She went from Zhengzhou to Chengdu.”

💬 “Seeing the world takes money,” some pointed out.

💬 But others came to her defense, saying that “seeing the world” also means stepping out of your comfort zone and exploring a different life. In the end, Gu certainly did just that.

💬 “She was quite courageous,” another commenter wrote: “She gave up a stable job to go and see the world. Perhaps her life didn’t end up so rich, but the experiences she gained are priceless.”

The world is still big, though, and there’s plenty left for Gu Shaoqiang to see.

Also read what we wrote about this in 2015: In The Digital Age, ‘Handwritten Weibo’ Have Become All The Rage

What’s Memorable

📚 This pick from our archive is from last year, about Fan Zeng (范曾), the famous Chinese calligrapher, who is turning 87 soon and has a wife 50 years his junior.

This week, some videos featuring Chinese theoretical physicist & Nobel Prize winner Yang Chen-Ning (杨振宁) circulated on social media. Yang is turning 103 this year. Still sharp of mind, and he takes a walk every day.

Yang Chen-ning

In this interview here, when asked about the secret to his longevity, he points to one thing above all: luck.

🍀 Mostly, he suggests it’s the luck of good genes. On his father’s side, diabetes was common, but he was fortunate to inherit his mother’s genes in that regard.

🍚 He also mentions the luck of never experiencing extreme hunger during wartime — he lived in Kunming during those years.

💪 And then he stresses the importance of taking walks, every day, since he was about 70. Keep moving, keep the blood flowing!

What he doesn’t mention, however, is that his wife, Weng Fang (翁帆), is 54 years (!) his junior — I’m pretty sure she helps keep him young too…

Fan and Yang are good friends, and Yang’s good health might have inspired him to marry his 50-years-younger girlfriend last year. Read more 👇

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Newsletter

The 315 Gala: A Night of Scandals, A Year of Distrust

From sanitary pads to shrimp: these were 315 Gala’s biggest scandals. It’s business as usual.

Published

1 week agoon

March 16, 2025

Dear Reader,

Since yesterday, China’s trending topic lists are all about recycled sanitary pads, unhygienic disposable underwear, and water-injected shrimp.

Why, you might wonder?

It has everything to do with the 35th edition of China’s consumer day show, ‘CCTV 3.15 Gala’ (3·15晚会). It aired on Saturday night, becoming one of the most-discussed topics on Chinese social media for exposing malpractices across various companies and industries.

The famous consumer rights show, which coincides with World Consumer Rights Day, is a joint collaboration between CCTV and government agencies. It has been broadcast live on March 15 since 1991.

Each year, the theme of the show varies slightly, but its core mission remains unchanged: to educate people on consumer rights and expose violations while holding companies accountable.

At the time of writing, topics exposed on the show are dominating trending & hot lists across multiple platforms, from Weibo to Douyin, and from Kuaishou to Toutiao.

Weibo’s hot trending list dominated by 315-related topics.

I’ll give you a quick walkthrough of three major stories that have sparked the most discussion online.

1️⃣🚨 “Recycled” Counterfeit Diapers & Sanitary Napkins

The first big story involves a company from Liangshan in Jining called Liangshan Xixi Paper Products (希希纸制品有限公司), which was exposed for selling so-called “refurbished” (翻新) sanitary pad and baby diapers.

The company’s owner, Mr. Liu (刘), bought up scraps and defective sanitary napkins and baby diapers from recognized brands for anything from 260 RMB ($36) to 1400 RMB ($193) per ton. He then repackaged and resold them to unsuspecting consumers, both online and offline, making significant profits.

The incident has a lot of impact. Some of the brands involved are big and reputable Chinese companies, including Freemore (自由点) and Sofy (苏菲), some of China’s most popular feminine hygiene brands.

On Saturday night, after the scandal was brought to light, virtually all of the brands involved halted their e-commerce livestreams. Behind the scenes, marketing crises teams gathered to create statements, which soon were published online.

Sofy responded by stating that the disposal of their non-conforming products is 100% handled within a closed-loop system, ensuring they cannot be resold or reused. They also denied manufacturing the products with their branding shown in the 315 Gala and pledged to fully cooperate with authorities to combat counterfeit and substandard goods (hashtag #苏菲发声明#, over 130 million views).

In response to this incident, the authorities in Jining have undertaken various actions. They have detained those responsible and launched a citywide campaign to oversee the production and sale of sanitary napkins and baby diapers.

In online comment sections, many Chinese netizens argue that the entire industry should be investigated to prevent similar violations from recurring, as this is not the first time such issues have come to light. How did products with defects end up for sale? How can people be sure that their diapers and sanitary pads aren’t counterfeit?

In 2024, there have been multiple online discussions about the safety of Chinese sanitary pads after an online film maker exposed how illegal factories are recycling used materials, including shredded pads and diapers, into new sanitary products. These contaminated pads, sold cheaply on e-commerce platforms, have been linked to pelvic inflammation and other gynecological problems.

2️⃣🚨 Disposable Underwear Sewn by Hand, Stored Next to Trash

The second major story revealed by the 315 Gala involves disposable underwear produced by local manufacturers in the city of Shangqiu. It was uncovered by investigative reporters that many of these manufacturers do not sterilize their disposable underwear products at all. They store them in unsanitary conditions, and use toxic chemicals. Additionally, they falsely advertise their products as 100% cotton when, in reality, they are made of polyester.

Disposable underwear has become more popular in China in recent years. This is not necessarily disposable incontinence underwear, or the kind you only see in hospitals, but it’s one-time wear underwear that is sold at Miniso or Watsons and promoted as a hygienic and convenient solution for workers or travelers, for use in hotels, spas, and beyond.

Among the various companies found to be violating production standards, one company (Mengyang Clothing 梦阳服饰) had a particularly chaotic production workshop. A reporter, going undercover as a potential buyer, entered the factory and saw how workers were sewing disposable underwear with bare hands, without any sterilization, and storing them right next to piles of garbage.

Among the brands involved are those regularly sold on platforms like Taobao, including Beiziyan (贝姿妍), Chuyisheng (初医生), and Langsha (浪莎). They’ve now been removed, and Shangqiu authorities have already established a joint task force to further tackle and investigate the situation.

A related hashtag (#一次性内裤爆雷#) has received over 310 million views by now on Weibo, showing just how concerned people are about the topic. Last year, one Douyin influencer (@黑犬酱·MO) also exposed a factory for the messy and chaotic circumstances under which they produce disposable underwear, after she ended up with a gynecological infection after wearing disposable underwear. Other people shared similar experiences.

3️⃣🚨 Shrimp, with an Extra Serving of Phosphates

The third big story exposed fraudulent practices in the seafood industry, where frozen shrimp suppliers were found illegally adding excessive amounts of phosphates as a water-retention agent.

Phosphates are widely used as food additives in seafood to preserve freshness and texture, but in this case, the process was exploited to artificially increase the weight of shrimp for profit.

One reporter uncovered a facility where shrimp were soaked in phosphates for over 10 hours, resulting in a phosphate content of 30%—far exceeding legal limits.

At another seafood facility, shrimp were rapidly frozen after chemical soaking, followed by an additional coating process to further increase weight. In some cases, only 30% of the final weight was actual shrimp after defrosting.

Beyond the deceptive nature of these practices, the overuse of phosphates poses serious health risks, including digestive issues, or increased risk of cardiovascular diseases.

One worker at the seafood plant interviewed by one of the reporters admitted that they never eat the shrimp they process, saying: “Here on the coast, we only eat fresh shrimp.”

🔁🇨🇳 Business as Usual

These stories, along with other brands and fraudulent practices exposed by CCTV, have sparked anger among netizens. Many women voiced concerns about the safety of sanitary pads. Others wondered about the quality of their seafood. Some vowed never to buy disposable underwear again. Parents angrily asked why they had to question the safety of the diapers for their babies.

An old Dutch saying goes, “Trust arrives on foot and leaves on horseback.” It can take years to build a reputation, but a single bad incident can ruin people’s trust in an instant. This is especially true in China, where public trust in well-known brands has been repeatedly shaken by scandals. A single product crisis can not only severely damage a company’s reputation, but even lead to an erosion of trust in the entire industry.

➡️ The most infamous and devastating example, which left a deep scar on consumer trust, was the 2008 melamine scandal, in which dairy manufacturers deliberately added melamine, an industrial chemical—to diluted raw milk to falsely boost its protein content. Among the infants and children who consumed the tainted milk, over 250,000 cases of health problems were reported. 52,000 children were hospitalized, and six infants lost their lives.

Although the milk powder scandal became a turning point for food and product safety regulations in China, leading to stricter oversight and improved industry standards, it also fueled deep consumer distrust. Even as Chinese brands worked to enhance quality and adopt international safety standards, many consumers remained hesitant to trust them.

➡️ Last year’s cooking oil scandal, involving transport trucks and cargo ships being used to carry both cooking oil and toxic chemicals without proper cleaning procedures, again fueled many discussions about public safety and if people can trust the products they use on a daily basis. It raised public concern not just about unsafe food-handling practices, but also about a myriad of other problems, including a lack of enforcement, bureaucratic inefficiency, power plays, public deception, and especially a lack of transparent communication in the aftermath of such scandals.

🔹 Somewhat ironically, CCTV’s 315 Gala is tackling precisely this issue. By exposing unsafe products and illegal business practices, the show puts brand names, details, and investigations into the public eye. In doing so, they help shape an online discourse where state media, local authorities, and consumers unite in their fight against industry misconduct.

At the end of the day, both brands and consumers have become familiar with the playbook that follows such crises when they are exposed on the 315 Gala.

🔍 Today, an interesting blog by Market News (市场资讯) published on Sina Finance (“开了24年的315晚会 四大规律你懂么”), voiced a critique of the Consumer Day show, arguing that the show, instead of an actual solution for China’s food & product safety, has become more like an annual ritualistic spectacle for the people, a cathartic pressure valve for public frustration.

The author observes four patterns in relation to scandals exposed on the show.

📌 Businesses & consumers follow the same old script

The apologies are ready, the bows are rehearsed, and the damage control strategies are in place.

After so many years of getting exposed, Chinese companies no longer panic after being featured on the show. They have their response templates prepared and a crisis strategy to manage public outrage. Meanwhile, e-commerce platforms swiftly cut ties with implicated brands and showcase new quality control measures, while consumers are comforted with apology letters and discount coupons before getting distracted by the next headlines.

📌 Authorities/regulators also stick to their routine playbook

Similarly, Chinese regulators have a scripted response ready to demonstrate their proactiveness in handling the situation. They quickly issue official statements, ensuring to include phrases like “immediate shutdown,” “ongoing investigation,” and “fines will be imposed.”

📌 The dark side of the industry will still be there

Big businesses prioritize profit over ethics, and as long as the profits outweigh the fines, companies will continue to test regulatory boundaries. There will always be loopholes to exploit, ensuring that these scandals will happen again.

📌 Only small companies face real consequences

While major corporations have the capital and resources to weather a public relations crisis, it is only the small companies without strong investor backing that fail to recover after being exposed on the 315 Gala. This also means that these scandals often don’t actually lead to industry reform.

Scrolling through Chinese social media today, it’s evident that the combined force of social media and the CCTV 315 Gala show has an immense impact.

But public outrage has a short lifespan.

The more consumers grow accustomed to scandals, the more consumer tolerance increases, and the more corporate ethics degrade.

Public distrust remains. The anger is there. But the scandals continue.

The CCTV 315 Gala provides an opportunity for everyone to be angry about it for a day.🔚

There were even more consumer scandals this week, which you can read about below. Special thanks to Miranda Barnes for her input and contributions to this week’s newsletter—be sure to check out her podcast recommendation as well.

Best,

Manya Koetse

(@manyapan)

What’s Trending

What’s Behind the Headlines

Last week and into the beginning of this week, the Two Sessions—China’s annual parliamentary meetings—were trending on Weibo and other Chinese social media platforms. Chinese online media were filled with coverage, yet Western newspapers had surprisingly little to say about these meetings.

I listened to a well-known podcast by two British political commentators: The Rest Is Politics, hosted by Alastair Campbell and Rory Stewart. They talked about how little the Western world has been reporting about the Two Sessions in China.

This is how the podcast was started by Campbell:

“(..) Because most of our media hasn’t bothered with it, we should talk about the China National Congress they just had (..) The reason I wanted to talk about China is that we are in this world where we all tell each other that there are two superpowers in the world: the United States and China. And the United States, we cover and discuss every single aspect of everything that’s been happening inside Donald Trump’s White House—(..), we’re even talking about the woman who walks alongside Trump carrying his bags and knocking the dandruff off his suit and all that sorts of stuff. And yet China has just held its Two Sessions, which is the National Congress and the big advisory body, and it’s as if it never happened.

Over the past few days, I’ve been asking people if they’re aware of anything big happening in China recently, and nobody knows.

Now, I won’t put you on the spot, Rory, because it would be too cruel, but if I asked people to name the seven members of the Chinese Communist Party Politburo Standing Committee—probably the seven most powerful people in China—most of our listeners won’t know.

So, is this a language thing? Is it because Trump floods the zone with so much shit that we just find ourselves poking in the turds, deciding which piece to focus on before he drops the next one?

Or is it that we maybe haven’t fully caught up with just how important China is now in terms of our lives, as much as their own?”

In this podcast, the two hosts acknowledged that Trump, and, of course, the ongoing war, dominate media coverage in the West. But they made a very valid point in questioning how people could be ignoring such a major political event in China, emphasizing just how crucial China is on the world stage.

They argued that mainstream media editors simply don’t prioritize China—not because there aren’t great journalists covering it, but because it’s not seen as a pressing topic. They also suggested that this lack of coverage isn’t always due to disinterest (there’s no doubt the world is interested in China), but that language and cultural barriers might also play a role.

Yet, as pointed out in the podcast, here we are: the West, living under Trump’s influence, reacting from tweet to tweet, tantrum to tantrum, while practically disregarding Xi’s long-term vision—his roadmap for China from 2021 to 2035 and then from 2035 to 2050—which follows a methodical strategy that will inevitably shape the future.

You can watch or listen to the podcast here.

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Popular Reads

-

China Insight11 months ago

China Insight11 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music12 months ago

China Music12 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

-

China Arts & Entertainment10 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment10 months agoSinging Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments