China Media

“Without Limits, There is No Freedom” – Controversial French Burkini Ban Goes Trending on Weibo

France’s ‘burkini’ bans recently sparked outrage on Twitter, where many netizens called them “racist” and “oppressive”. On Chinese social media, however, many netizens seem to support the French ban on Islamic swimwear, while other Weibo users just don’t understand what all the “fuss” is about

Published

8 years agoon

France’s ‘burkini’ bans recently sparked outrage on Twitter, where many netizens called them “racist” and “oppressive”. On Chinese social media, however, many netizens seem to support the French ban on Islamic swimwear, while other Weibo users just don’t understand what all the “fuss” is about.

On Weibo, various Chinese media recently reported about mayors in different French cities banning the ‘burkini’, a type of Islamic swimwear for women. The news of the ban, and photographs of police allegedly asking a woman to remove her conservative beachwear, were shared amongst Chinese netizens and attracted many comments.

On Twitter, the ban has led to a stream of angry reactions, with many calling it “oppressive”, “racist” and “absurd”, while defending wearing the right to wear a burkini as “the right to cover up”.

The French burkini bans are based on ideas that the body wear item is “not just a casual choice”, but “part of an attempt by political Islamism to win recruits and test the resilience of the French republic” (Economist 2016). The bans come after a series of deadly terrorist attacks over the past 1,5 years.

Religious neutrality is a value that has been strongly upheld in France, where the government adheres to a strict form of secularism known as laïcité – designed to keep religion out of public life (Economist 2014). Since 2004, wearing conspicuous religious symbols in public schools became illegal. According to Brookings, that law was widely condemned in the United States, where high schools allow students to wear head scarfs, Jewish caps, large Christian crosses, or other conspicuous religious signs.

But French supporters argued that in the existing social, political and cultural context of France, they could not tolerate these religious symbols. In 2010, wearing a full face veil was also prohibited by law.

“Don’t you get it? This is all for the safety of the country.”

On August 24, Chinese news site The Observer (观察者网) posted on Weibo: “Where are the human rights? French police force women to take off her muslim swimwear. Recently, at a beach in the French city of Nice, French police requested a woman to take off her muslim swimwear, which triggered much controversy. At the time, the woman was wearing a so-called ‘burkini’ (布基尼) while sunbathing. Four tall men went to her while holding their police stick and pepper-spray.”

The post, just one out of many micro-blogs posted on this topic on Sina Weibo, attracted near 6000 comments. The most popular comment (i.e. receiving the most ‘likes’ from other netizens) said: “The rule of France banning clear religious symbols in public does not just apply to muslims. This rule is the same for all religions.”1

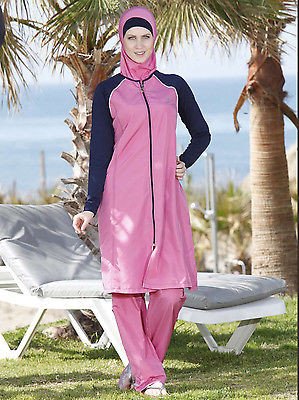

A burkini sold on a swimwear website.

A burkini sold on a swimwear website.

The number two most popular comment read: “Don’t blame the police for this! France is afraid to get bombed! They are afraid of people hiding bombs in their clothing in crowded places.”2

“Don’t you get it? This is all for the safety of the country,” the following commenter wrote.3

“Freedom is not unlimited, freedom is relative, freedom is limited – without limits, there is no freedom.”

Many Chinese netizens see the burkini ban as a direct consequence of the strings of islamist terrorist attack occurring in France over the past 18 months. “This is how it should be, China is the same, there can be no exemptions,”4 one netizen says.

In China, a ban on wearing burqa’s, or ‘face masking veils’ (蒙面罩袍), was legally approved in January of 2015. The prohibition on burqa’s applies specifically to Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang, home to the majority of China’s muslims.

A year earlier, Chinese authorities also implemented several measures in Xinjiang to keep religious expressions to a minimum after a string of attacks allegedly committed by Chinese muslim extremists. The measures, amongst others, did not allow fasting for Ramadan, no niqabs, hijabs or large beards in buses.

[rp4wp]

Underneath a Weibo post on the burkini ban by China’s Lifeweek (@三联生活周刊), the number one popular comment says: “To all the people here saying that what you wear is a personal freedom: it was also enforced that women could no longer have bound feet [in China], with the police parading the foot binding cloths out in the streets. Some women felt so humiliated that they committed suicide. Do you also feel that their right needed to be defended? (..) Freedom is not unlimited, freedom is relative, freedom is limited – without limits, there is no freedom.”5

” What is all the fuss about?”

But not all netizens agree with these views. One micro-blogger, who goes by the name of ‘Demons and Monsters‘, said: “Although I am opposed to the burqa, I am also against the enforcement of wearing less clothing. What if you caught a cold? You are an endangerment to others if you fully cover yourself in a public place, but it is your freedom not to expose too much.”

“What about the West and its human rights? Its freedom of religion?” another Weibo user remarks.6

Noteworthy about the burkini ban issue on Weibo, is that although (state) media seem to denounce it in their reporting (“Where are the human rights?”), the majority of netizens seem to support it. When Chinese news site Jiemian posted the news on Weibo saying: “A setback for freedom? Three cities in France prohibit muslim swimsuits”, it got the response from netizens: “A setback? This is progression!”7, and others saying: “People keep mentioning human rights, and freedom. Take a look at Europe’s terrorist attacks – what does it [still] mean?”8

“When you come to a place, you follow their guidelines and customs. This is normal. It is also a way of showing respect to the local [culture]. What is all the fuss about? Should muslims be an exception to the rule?”, one 45-year-old Weibo user from Shandong writes.

“I thought we were talking about facekini’s here.”

Another person compares the burkini to the Japanese kimono: “I think a lot of people here do not understand the feeling of French people. For example, what if you would walk down the street and see that in China people are wearing kimono’s? When in Rome, do as the Romans do, or just go back to your own country. Don’t use religion as an excuse.”9

Although the majority of the netizen’s reactions on Weibo are different than those on Twitter, a recurring issue on both social media networks is the focus on ‘freedom’, with some Chinese netizens emphasizing the fact that what you wear is your own freedom. But the most-liked comments on Weibo are those stressing that freedom is relative: “Many people say that a woman can wear what she likes, that it’s her freedom. But did you ever think about whether these women have the freedom not to wear it? They clearly don’t.”10

There are also those who confuse the ‘burkini’ (布基尼) with China’s ‘facekini‘ (脸基尼) (“I thought we were talking about facekini’s for a moment!“), although for now, it is highly likely that neither are welcome on the beaches of Nice.

China’s infamous ‘facekini’

China’s infamous ‘facekini’

– By Manya Koetse

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

1 “但其实法国禁止民众在公共场合显露出明显的宗教标志的规定,不只是针对穆斯林。 这个法规对各大宗教是平等的,比如在公共场所佩戴十字架,佩戴佛珠,严格的说,都是不符合法规的。”

2 “别喷警察了!法国是被炸怕了 就怕人群密集的地方 衣服里那么厚有藏炸弹”

3 “那是为了国家安全,你懂个屁[doge]”

4“必须这样,中国的也一样,不能搞特殊化”

5 “评论里谈到穿什么是个人自由,当年女性不能再裹脚也是强制性的,警察们挑着裹脚布招摇过市,无数女性感觉被羞辱自杀,你是否认为她们的自由也应该被捍卫?就是现在很多女性也自愿回家自愿生多胎自愿流产自愿被打死,她们的自由呢?自由不是无限的,自由是相对的,自由是受限的,没有限制就没有自由。”

6 西方的人权呢?宗教自由呢?

7“这是倒退?这是进步!”

8“还有人提人权,自由。不看看欧洲被恐袭搞成什么了么?”

9 “我看很多人不了解法国人是怎样一种感受,打个比方,就跟你走在街上看到中国有人穿和服的时候[微笑]所谓入乡要随俗,不然真的请回自己国家。别拿宗教当借口这里不适合这样的宗教,你为何还来呢?”

10“很多人都说那些女性喜欢穿什么就穿什么,是她们的自由。但是洗地的那些人有没有想过,她们有不穿这个的自由吗,很明显没有”

©2016 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

[showad block=2]

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Media

Hu Xijin’s Comeback to Weibo

After 90 days of silence, Hu Xijin is back on Weibo—but not everyone’s thrilled.

Published

20 hours agoon

November 7, 2024

A SHORTER VERSION OF THIS ARTICLE WAS PART OF THE MOST RECENT WEIBO WATCH NEWSLETTER.

For nearly 100 days, since July 27, the well-known social and political commentator Hu Xijin (胡锡进) remained silent on Chinese social media. This was highly unusual for the columnist and former Global Times editor-in-chief, who typically posts multiple Weibo updates daily, along with regular updates on his X account and video commentaries. His Weibo account boasts over 24.8 million followers.

Various foreign media outlets speculated that his silence might be related to comments he previously made about the Third Plenum and Chinese economics, especially regarding China’s shift to treating public and private enterprises equally. But without any official statement, Chinese netizens were left to speculate about his whereabouts.

Most assumed he had, in some way, taken a “wrong” stance in his commentary on the economy and stock market, or perhaps on politically sensitive topics like the Suzhou stabbing of a Japanese student, which might have led to his being sidelined for a while. He certainly wouldn’t be the first prominent influencer or celebrity to disappear from social media and public view—when Alibaba’s Jack Ma seemed to have fallen out of favor with authorities, he went missing, sparking public concern.

After 90 days of absence, the most-searched phrases on Weibo tied to Hu Xijin’s name included:

胡锡进解封 “Hu Xijin ban lifted”

胡锡进微博解禁 “Hu Xijin’s Weibo account unblocked”

胡锡进禁言 “Hu Xijin silenced”

胡锡进跳楼 “Hu Xijin jumped off a building”

On October 31, Hu suddenly reappeared on Weibo with a post praising the newly opened Chaobai River Bridge, which connects Beijing to Dachang in Hebei—where Hu owns a home—significantly reducing travel time and making the more affordable Dachang area attractive to people from Beijing. The post received over 9,000 comments and 25,000 likes, with many welcoming back the old journalist. “You’re back!” and “Old Hu, I didn’t see you on Weibo for so long. Although I regularly curse your posts, I missed you,” were among the replies.

When Hu wrote about Trump’s win, the top comment read: “Old Trump is back, just like you!”

Not everyone, however, is thrilled to see Hu’s return. Blogger Bad Potato (@一个坏土豆) criticized Hu, claiming that with his frequent posts and shifting views, he likes to jump on trends and gauge public opinion—but is actually not very skilled at it, allegedly contributing to a toxic online environment.

Other bloggers have also taken issue with Hu’s tendency to contradict himself or backtrack on stances he takes in his posts.

Some have noted that while Hu has returned, his posts seem to lack “soul.” For instance, his recent two posts about Trump’s win were just one sentence each. Perhaps, now that his return is fresh, Hu is carefully treading the line on what to comment on—or not.

Nevertheless, a post he made on November 3rd sparked plenty of discussion. In it, Hu addressed the story of math ‘genius’ Jiang Ping (姜萍), the 17-year-old vocational school student who made it to the top 12 of the Alibaba Global Mathematics Competition earlier this year. As covered in our recent newsletter, the final results revealed that both Jiang and her teacher were disqualified for violating rules about collaborating with others.

In his post, Hu criticized the “Jiang Ping fever” (姜萍热) that had flooded social media following her initial qualification, as well as Jiang’s teacher Wang Runqiu (王润秋), who allegedly misled the underage Jiang into breaking the rules.

The post was somewhat controversial because Hu himself had previously stated that those who doubted Jiang’s sudden rise as a math talent and presumed her guilty of cheating were coming from a place of “darkness.” That post, from June 23 of this year, has since been deleted.

Despite the criticism, some appreciate Hu’s consistency in being inconsistent: “Hu Xijin remains the same Hu Xijin, always shifting with the tide.”

Hu has not directly addressed his absence from Weibo. Instead, he shared a photo of himself from 1978, when he joined the military. In that post, he reflected on his journey of growth, learning, and commitment to the country. Judging by his renewed frequency of posting, it seems he’s also recommitted to Weibo.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Arts & Entertainment

Controversial Wanghong Livestreamers Are Becoming a Weibo Staple in China

‘Wanghong’ was a mark of online fame; now, it’s increasingly tied to controversy and scandal.

Published

2 weeks agoon

October 27, 2024

As livestreaming continues to gain popularity in China, so do the controversies surrounding the industry. Negative headlines involving high-profile livestreamers, as well as aspiring influencers hoping to make it big, frequently dominate Weibo’s trending topics.

These headlines usually revolve around China’s so-called wǎnghóng (网红) influencers. Wanghong is a shortened form of the phrase “internet celebrity” (wǎngluò hóngrén 网络红人). The term doesn’t just refer to internet personalities but also captures the viral nature of their influence—describing content or trends that gain rapid online attention and spread widely across social media.

Recently, an incident sparked debate over China’s wanghong livestreamers, focusing on Xiaohuxing (@小虎行), a streamer with around 60,000 followers on Douyin, who primarily posts evaluations of civil aviation services in China.

Xiaohuxing (@小虎行)

On October 15, 2024, at Shenzhen Bao’an International Airport, Xiaohuxing confronted a volunteer at the automated check-in counter, insisting she remove her mask while livestreaming the entire encounter. He was heard demanding, “What gives you the right to wear a mask? What gives you the right not to take it off?” and even attempted to forcibly remove her mask, challenging her to call the police.

During the livestream, the livestreamer confronted the woman on the right for wearing a facemask.

He also argued with a male traveler who tried to intervene. In the end, the airport’s security officers detained him. Shortly after the incident, a video of the livestream went viral on Weibo under various hashtags (e.g. #网红小虎行机场强迫志愿者摘口罩#) and attracted millions of views. The following day, Xiaohuxing’s Douyin account was banned, and all his videos were removed. The Shenzhen Public Security Bureau later announced that the account’s owner, identified as Wang, had been placed in administrative detention.

On October 13, just days before, another livestreaming controversy erupted at Guangzhou Baiyun International Airport. Malatang (@麻辣烫), a popular Douyin streamer with over a million followers, secretly filmed a young couple kissing and mocked them, continuing to film while passing through security—an area where filming is prohibited.

Her livestream quickly went viral, sparking discussions about unauthorized filming and misconduct among Chinese wanghong. In response, Malatang’s agent posted an apology video. However, the affected couple hired a lawyer and reported the incident to the police (#被百万粉丝网红偷拍当事人发声#). On October 17, Malatang’s Douyin account was banned, and her videos were removed.

Livestreamer Malatang making fun of the couple in the back at the airport.

In both cases, netizens uncovered additional examples of inappropriate behavior by Xiaohuxing and Malatang in past broadcasts. For example, Xiaohuxing was reportedly aggressive towards a flight attendant, demanding she kneel to serve him, while Malatang was criticized for scolding a delivery person who declined to interact with her on camera.

Comments on Weibo included, “They’ll do anything for traffic. Wanghong are getting a bad reputation because of people like this.” Another added, “It seems as if ‘wanghong’ has become a negative term now.”

Rising Scrutiny in China’s Wanghong Economy

Xiaohuxing and Malatang are far from isolated cases. Recently, many other wanghong livestreamers have also been caught up in negative news.

One such figure is Dong Yuhui (董宇辉), a former English teacher at New Oriental (新东方) who transitioned to livestreaming for East Buy (东方甄选), where he mixed education with e-commerce (read here). Dong gained significant popularity and boosted East Buy’s brand before leaving to start his own company. Recently, however, Dong faced backlash for inaccurate statements about Marie Curie during an October 9 livestream. He incorrectly claimed that Curie discovered uranium, invented the X-ray machine, and won the Nobel Prize in Literature, among other things.

Considering his public image as a knowledgeable “teacher” livestreamer, this incident sparked skepticism among viewers about his actual expertise. A related hashtag (#董宇辉称居里夫人获得诺贝尔文学奖#) garnered over 81 million views on Weibo. In addition to this criticism, Dong is also being questioned about potential false advertising, which is a major challenge for all livestreamers selling products during their streams.

Dong Yuhui (董宇辉) during one of his livestreams.

Another popular livestreamer, Dongbei Yujie (@东北雨姐), is currently also facing criticism over product quality and false advertising claims. Originally from Northeast China, Dongbei Yujie shares content focused on rural life in the region. Recently, her Douyin account, which boasts an impressive 22 million followers, was muted due to concerns over the quality of products she promoted, such as sweet potato noodles (which reportedly contained no sweet potato). Despite issuing public apologies—which have garnered over 160 million views under the hashtag “Dongbei Yujie Apologizes” (#东北雨姐道歉#)—the controversy has impacted her account and led to a penalty of 1.65 million yuan (approximately 231,900 USD).

From Dongbei Yujie’s apology video

Former top Douyin livestreamer Fengkuang Xiaoyangge (@疯狂小杨哥) is also facing a career downturn. Leading up to the 2024 Mid-Autumn Festival, he promoted Hong Kong Meicheng mooncakes in his livestreams, branding them as a high-end Hong Kong product. However, it was soon revealed that these mooncakes had no retail presence in Hong Kong and were primarily produced in Guangzhou and Foshan, sparking accusations of deceptive marketing. Due to this incident and previous cases of misleading advertising, his company came under investigation and was penalized. In just a few weeks, Fengkuang Xiaoyangge lost over 8.5 million followers (#小杨哥掉粉超850万#).

Fengkuang Xiaoyangge (@疯狂小杨哥) and the mooncake controversy.

It’s not only ecommerce livestreamers who are getting caught up in scandal. Recently, the influencer “Xiaoxiao Nuli Shenghuo” (@小小努力生活) and her mother were arrested for fabricating a tragic story – including abandonment, adoption, and hardships – to gain sympathy from over one million followers and earn money through donations and sales. They, and two others who helped them manage their account, were sentenced to ten days in prison for ‘false advertising.’

Wanghong Fame: Opportunity and Risk

China’s so-called ‘wanghong economy’ has surged in recent years, with countless content creators emerging across platforms like Douyin, Kuaishou, and Taobao Live. These platforms have transformed interactions between content creators and viewers and changed how products are marketed and sold.

For many aspiring influencers, becoming a livestreamer is the first step to building a presence in the streaming world. It serves as a gateway to attracting traffic and potentially monetizing their online influence.

However, before achieving widespread fame, some livestreamers resort to using outrageous or even offensive content to capture attention, even if it leads to criticism. For example, before his account was banned, Xiaohuxing set his comment section to allow only followers to comment, gaining 3,000 new followers after his controversial livestream at Shenzhen Airport went viral. Many speculated that some followers joined just to leave critical comments, but it nonetheless grew his following.

As livestreamers gain significant fame, they must exercise greater caution, as they often hold substantial influence over their audiences, making accuracy essential. Mistakes, whether intentional or not, can quickly erode trust, as seen in the example of the super popular Dong Yuhui, who faced backlash after his inaccurate comment about Marie Curie sparked public criticism.

China’s top makeup livestreamer, Li Jiaqi (李佳琦), experienced a similar reputational crisis in September last year. Responding dismissively to a viewer who commented on the high price of an eyebrow pencil, Li replied, “Have you received a raise after all these years? Have you worked hard enough?” Commentators pointed out that the pencil’s cost per gram was double that of gold at the time. Accused of “forgetting his roots” as a former humble salesman, Li lost one million Weibo followers in a day (read more here).

This meme shows that many viewers did not feel moved by Li’s apologetic tears after the eyepencil incident.

Despite the challenges and risks, becoming a wanghong remains an attractive career path for many. A mid-2023 Weibo survey on “Contemporary Employment Trends” showed that 61.6% of nearly 10,000 recent graduates were open to emerging professions like livestreaming, while 38.4% preferred more traditional career paths.

Taming the Wanghong Economy

In response to the increasing number of controversies and scandals brought by some wanghong livestreamers, Chinese authorities are implementing stricter regulations to monitor the livestreaming industry.

In 2021, China’s Propaganda Department and other authorities began emphasizing the societal influence of online influencers as role models. That year, the China Association of Performing Arts introduced the “Management Measures for the Warning and Return of Online Hosts” (网络主播警示与复出管理办法), which makes it challenging, if not impossible, for “canceled” celebrities to stage a comeback as livestreamers (read more).

The Regulation on the Implementation of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Consumer Rights and Interests (中华人民共和国消费者权益保护法实施条例), effective July 1, 2024, imposes stricter rules on livestream sales. It requires livestreams to disclose both the promoter and the product owner and mandates platforms to protect consumer rights. In cases of illegal activity, the platform, livestreaming room, and host are all held accountable. Violations may result in warnings, confiscation of illegal earnings, fines, business suspensions, or even the revocation of business licenses.

These regulations have created a more controlled “wanghong” economy, a marked shift from the earlier, more unregulated era of livestreaming. While some view these measures as restrictive, many commenters support the tighter oversight.

A well-known Kuaishou influencer, who collaborates with a person with dwarfism, recently faced backlash for sharing “vulgar content,” including videos where he kicks his collaborator (see video) or stages sensational scenes just for attention.

Most commenters welcome the recent wave of criticism and actions taken against such influencers, including Xiaohuxing and Dongbei Yujie, for their behavior. “It’s easy to become famous and make money like this,” commenters noted, adding, “It’s good to see the industry getting cleaned up.”

State media outlet People’s Daily echoed this sentiment in an October 21 commentary, stating, “No matter how many fans you have or how high your traffic is, legal lines must not be crossed. Those who cross the red line will ultimately pay the price.”

This article and recent incidents have sparked more online discussions about the kind of influencers needed in the livestreaming era. Many suggest that, beyond adhering to legal boundaries, celebrity livestreamers should demonstrate a higher moral standard and responsibility within this digital landscape. “We need positive energy, we need people who are authentic,” one Weibo user wrote.

Others, however, believe misbehaving “wanghong” livestreamers naturally face consequences: “They rise fast, but their popularity fades just as quickly.”

When asked, “What kind of influencers do we need?” one commenter responded, “We don’t need influencers at all.”

By Wendy Huang

Follow @whatsonweibo

Edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Subscribe

Hu Xijin’s Comeback to Weibo

Weibo Watch: “Comrade Trump Returns to the Palace”

The Price of Writing Smut: Inside China’s Crackdown on Erotic Fiction

Controversial Wanghong Livestreamers Are Becoming a Weibo Staple in China

The Viral Bao’an: How a Xiaoxitian Security Guard Became Famous Over a Pay Raise

About Wang Chuqin’s Broken Paddle at Paris 2024

“Land Rover Woman” Sparks Outrage: Qingdao Road Rage Incident Goes Viral in China

China at Paris 2024 Olympics Trend File: Medals and Moments on Chinese Social Media

Weibo Watch: The Land Rover Woman Controversy Explained

Stolen Bodies, Censored Headlines: Shanxi Aorui’s Human Bone Scandal

Fired After Pregnancy Announcement: Court Case Involving Pregnant Employee Sparks Online Debate

Weibo Watch: Going the Wrong Way

Team China’s 10 Most Meme-Worthy Moments at the 2024 Paris Olympics

Weibo Watch: Shaping Olympic Narratives

“No Kimonos Allowed” – Ongoing Debate on Japanese Attire in China

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight6 months ago

China Insight6 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music7 months ago

China Music7 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Insight8 months ago

China Insight8 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Insight12 months ago

China Insight12 months agoThe Story of Li Jun & Liang Liang: How the Challenges of an Ordinary Chinese Couple Captivated China’s Internet