China ACG Culture

Chinese Woman Taken Away by Suzhou Police for Wearing Japanese Kimono

The Chinese cosplayer was taken away by police for dressing up as a Japanese manga character: “You are wearing a kimono, as a Chinese. You are Chinese!”

Published

3 years agoon

A Chinese female cosplayer who was dressed in a Japanese summer kimono while taking pictures in Suzhou’s ‘Little Tokyo’ area was taken away by local police for ‘provoking trouble.’ The incident has sparked concerns on Chinese social media.

A Chinese woman who was making street pictures of herself while dressed in a kimono was taken away by local Suzhou police for “picking quarrels” and “provoking trouble.”

A video that circulated on Chinese social media this week showed the local policeman talking to the young woman and screaming at her for wearing the Japanese kimono, suggesting she is not allowed to do so as a Chinese person.

A young Chinese woman was taken away by local police in Suzhou last Wednesday because she was wearing a kimono. "If you would be wearing Hanfu (Chinese traditional clothing), I never would have said this, but you are wearing a kimono, as a Chinese. You are Chinese!" pic.twitter.com/et8vWOferQ

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) August 15, 2022

“If you would be wearing Hanfu [Chinese traditional clothing], I would never have said this,” the policeman can be heard saying: “But you are wearing a kimono, as a Chinese. You are Chinese!” The video stops when the girl is taken away.

The incident happened on August 10 at Huaihai Street in Suzhou New District. Huaihai Street is also called “Little Tokyo” because the area is home to many Japanese businesses and restaurants.

The girl, who was previously active on Weibo under the nickname ‘Shadow not Self’ (是影子不是本人) is known to be a cosplayer, someone who likes to dress up a as a character from anime, TV show, or other works of fiction.

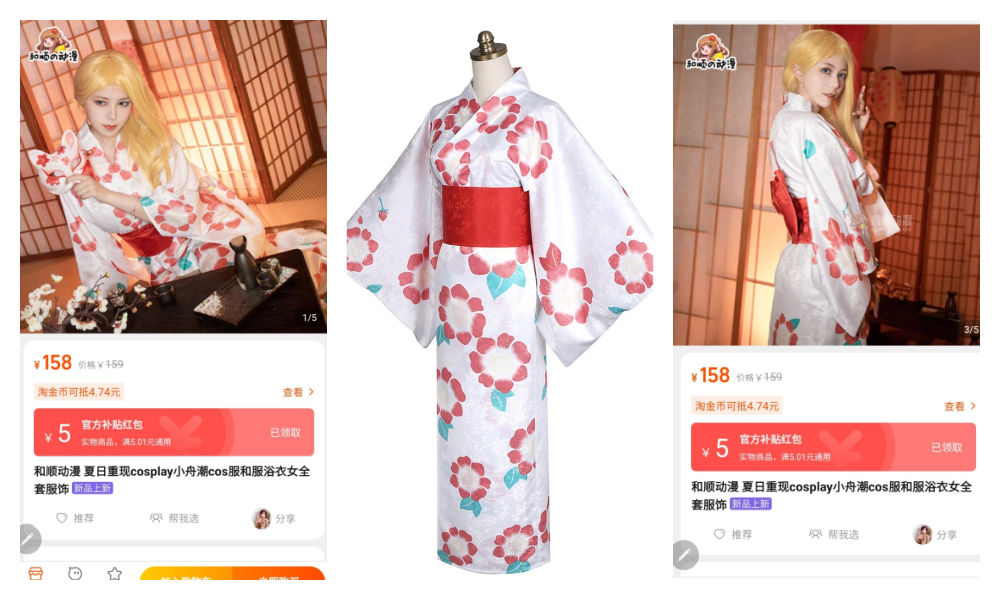

On the evening of August 10, she dressed up as the character Ushio Kofune from the Japanese manga series Summer Time Rendering, wearing a cotton summer kimono, better known as yukata. After she took some pictures to reenact a scene from the fictional work, she waited for her order at a local takoyaki place when the local officers approached her and eventually took her away.

According to a social media post by ‘Shadow not Self,’ she was released from the police station five hours later after she received some ‘education’ and police investigated the contents of her phone.

The scene from Summer Time Rendering that ‘Shadow not Self’ wanted to reenact while doing cosplay in Suzhou’s Huaihai street.

The incident first started surfaced on Chinese social media on the night of August 14 and then went viral on August 15, which marked the 77th anniversary of Japan’s surrender in World War II.

“Has even cosplay become dangerous now?” some commenters on Weibo wondered, with others calling the actions by the police “scary.”

“It’s just cosplay!” “How did she break the law?” many wondered, with some people calling the officer “incompetent.”

The kimono worn by ‘Shadow not Person’ is sold on Taobao for 158 yuan ($23).

Chinese political commentator Hu Xijin (@胡锡进) also weighed in on the issue via his social media channel (#胡锡进谈女孩穿和服被带走#). Although emphasizing the legal right Chinese citizens have to wear a kimono in public, Hu also mentioned that at a time of tense Sino-Japanese relations – noting Japan’s cooperation with the U.S. “to contain China” – there is a growing antipathy towards Japan, resulting in different perceptions of what it means to wear a kimono.

Nevertheless, Hu wrote, “a kimono is not a Japanese military uniform, and there is no legal reason why it should be banned.”

Hu also warned: “But when someone wants to wear a kimono, I would advise them to pay attention to their surroundings to prevent causing displeasure to those around them and, more importantly, to try to avoid becoming the center of unnecessary controversy themselves. There’s nothing wrong with respecting the feelings of the majority.”

Later on Monday night, CCTV uncoincidentally promoted a topic (#穿汉服就是回到古代吗#) related to wearing Hanfu or traditional Chinese clothing, writing: “As Chinese national traditional clothing, Hanfu can be fully integrated into modern daily life. (..) Change into Hanfu, let the beautiful culture move forward in a new era!”

By Manya Koetse

With contributions by Miranda Barnes and Xianyu Wang

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our weekly newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2022 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China ACG Culture

Beyond the Box Office: What’s Behind Ne Zha 2’s Success?

The impact of Ne Zha 2 goes beyond box office figures—yet, in the end, it’s the numbers that matter most.

Published

1 month agoon

February 27, 2025

FROM THE WEIBO WATCH PREMIUM NEWSLETTER

These days, everybody is talking about Ne Zha 2 (哪吒2:魔童闹海), the recent hit film about one of China’s most legendary mythological heroes. With its spectacular visuals, epic battles, funny characters, dragons and deities, and moving scenes, the Chinese blockbuster animation is breaking all kinds of records and has gone from the major hit of this year’s Spring Festival film season to the 7th highest-grossing movie of all time and, with its 13.8 billion yuan ($1.90 billion USD) box office success, now also holds the title of the most successful animated film ever worldwide.

But there is so much more behind this movie than box office numbers alone. There is a collective online celebration surrounding the film, involving state media, brands, and netizens. On Weibo, a hashtag about the movie crossing the 10 billion yuan ($1.38 billion) milestone (#哪吒2破100亿#) has been viewed over a billion times. Social media timelines are filled with fan art, memes, industry discussions, and box office predictions.

The success of Ne Zha 2 is not just a win for China’s animation industry but for “Made in China” productions as a whole. Some argue that Ne Zha‘s triumph is not just cultural but also political, reinforcing China’s influence on the global stage and tying it to the ongoing US-China rivalry: after growing its power in military strength, technology, and AI, China is now making strides in cultural influence as well.

In a recent Weibo post, state broadcaster CCTV also suggested that Hollywood has lost its monopoly over the film industry and should no longer count on the Chinese market—the world’s second-largest movie market—for its box office dominance.

Various images from “Ne Zha 2” 哪吒2:魔童闹海

The success of Ne Zha 2 mainly resonates so deeply because of the past failures and struggles of Chinese animation (donghua 动画). For years, China’s animation industry struggled to compete with American animation studios and Japanese anime, while calls grew louder to find a uniquely Chinese recipe for success—to make donghua great again.

🔹 The Chinese Animation Dream

A year ago, another animated film was released in China—and you probably never heard of it. That film was Ba Jie (八戒之天蓬下界), a production that embraced Chinese mythology through the story of Zhu Bajie, the half-human, half-pig figure from the 16th-century classic Journey to the West (西游记). Ba Jie was a blend of traditional Chinese cultural elements with modern animation techniques, and was seen as a potential success for the 2024 Spring Festival box office race. It took eight years to go from script to screen.

But it flopped.

The film faced numerous setbacks, including significant production delays in the Covid years, limited showtime slots in cinemas, and, most importantly, a very cold reception from the public. On Douban, China’s biggest film review platform, many top comments criticized the movie’s unpolished animation and special effects, and complained that this film—like many before it—was yet another Chinese animation retelling a repetitive story from Journey to the West, one of the most popular works of fiction in China.

“Another mythological character, the same old story,” some wrote. “We’re not falling for low-quality films like this anymore.”

The frustration wasn’t just about Ba Jie—it was about China’s animation industry as a whole. Over the past decade, the quality of Chinese animation films has become a much-discussed topic on social media in China—sometimes sparked by flops, and other times by hits.

Besides Ba Jie, one of those flops was the 2018 The King of Football (足球王者), which took approximately 60 million yuan ($8.8 million) to make, but only made 1.8 million yuan ($267,000) at the box office.

Both Ba Jie, which took years to reach the screen, and King of Football, a high-budget animation, ended up as flops.

One of those successes was the 2019 first Ne Zha film (哪吒之魔童降世), which became China’s highest grossing animated film, or, of the same year, the fantasy animation White Snake (白蛇:缘起), a co-production between Warner Bros and Beijing-based Light Chaser Animation (also the company behind the Ne Zha films). These hits

showed the capabilities and appeal of made-in-China donghua, and sparked conversations about how big changes might be on the horizon for China’s animation industry.

“The only reason Chinese people don’t know we can do this kind of quality film is because we haven’t made any good stories or good films yet,” White Snake filmmaker Zhao Ji (赵霁) said at the time: “We have the power to make this kind of quality film, but we need more opportunities.”

More than just entertainment, China’s animated films—whether successes or failures—have come to symbolize the country’s creative capability. Over the years, and especially since the widespread propagation of the Chinese Dream (中国梦)—which emphasizes national rejuvenation and collective success—China’s ability to produce high-quality donghua with a strong cultural and artistic identity has become increasingly tied to narratives of national pride and soft power. A Chinese animation dream took shape.

🔹 The “Revival” of China’s Animation Industry

A key part of China’s animation dream is to create a 2.0 version of the “golden age” of Chinese animation.

This high-performing era, which took place between 1956 and 1965, was led by the Shanghai Animation Film Studio. While China’s leading animators were originally inspired by American animation (including Disney’s 1937 Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs), as well as German and Russian styles, they were committed to developing a distinctly Chinese animation style—one that incorporated classical Chinese literature, ink painting, symbolism, folk art, and even Peking opera.

Some of the most iconic films from this era include The Conceited General (骄傲的将军, 1956), Why Crows Are Black (乌鸦为什么是黑的, 1956), and most notably, Havoc in Heaven (大闹天宫, 1961 & 1964). Focusing on the legendary Monkey King, Sun Wukong (孙悟空), Havoc in Heaven remains one of China’s most celebrated animated films. On Douban, users have hailed it as “the pride of our domestic animation.”

One of China’s most renowned animation masters, Te Wei (特伟), once explained that the flourishing of China’s animation industry during this golden era was made possible by state support, a free creative atmosphere, a thriving production system, and multiple generations of animators working together at the studio.

Still from Havoc in Heaven 大闹天宫 via The Paper.

➡️ So what happened to the golden days of Chinese animation?

The decline of this golden era was partly due to the political turmoil of the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). While there was a second wave of successful productions in the late 1970s and 1980s, the industry lost much of its ‘magic touch’ in the 1990s and 2000s. During this period, Chinese animation studios were pressured to prioritize commercial value, adhere to strict content guidelines, and speed up production to serve the rising domestic TV market—while also taking on outsourcing work for overseas productions.

As the quality and originality of domestic productions lagged behind, the market came to be dominated by imported (often pirated) foreign animations. Japanese series like Astro Boy, Doraemon, and Chibi Maruko-chan became hugely influential among Chinese youth in the 1990s. The strong reaction in China to the 2024 death of Japanese manga artist Akira Toriyama, creator of Dragon Ball, also highlighted the profound impact of Japanese animation on the Chinese market.

This foreign influence also changed viewers’ preferences and aesthetic standards, and many Chinese animations adopted more Japanese or American styles in their creations.

However, this foreign ‘cultural invasion’ was not welcomed by Chinese authorities. As early as 1995, President Jiang Zemin reminded the Shanghai Animation Film Studio of the ideological importance of animation, emphasizing that China needed its “own animated heroes” to serve as “friends and examples” for Chinese youth.

By the early 2010s, the revitalization and protection of China’s animation industry became a national priority. This was implemented through various policies and incentives, including government funding, tax reductions and exemptions for Chinese animation companies, national animation awards, stipulations for the number of broadcasted animations that must be China-made. Additionally, there was an increased emphasis on animation as a tool for cultural diplomacy, focusing on how Chinese animation should reflect national values and history while maintaining global appeal.

It’s important to note that the so-called ‘rejuvenation’ of Chinese animation is not just a cultural and ideological project, there are economic motives at stake too: China’s animation industry is a multi-billion dollar industry.

🔹 “Are We Ne Zha or the Groundhogs?”

The huge success of Ne Zha 2 is seen as a new milestone for Chinese animation and as inspiration for audiences. The film took about five years to complete, reportedly involving 140 animation studios and over 4,000 staff members. The film was written and overseen by director Yang Yu (杨宇), better known as Jiaozi (饺子).

The story is all based on Chinese mythology, following the tumultuous journey of legendary figures Nezha (哪吒) and Ao Bing (敖丙), both characters from the 16th-century classic Chinese novel Investiture of the Gods (Fengshen Yanyi, 封神演义). Unlike Ba Jie or other similar films, the narrative is not considered repetitive or cliché, as Ne Zha 2 incorporates various original interpretations and detailed character designs, even showcasing multiple Chinese dialects, including Sichuan, Tianjin, and Shandong dialects.

One of the film’s unexpected highlights is its clan of comical groundhogs. In this particularly popular scene, Nezha engages in battle against a group of groundhogs (土拨鼠), led by their chief marmot (voiced by director Jiaozi himself). Amid the fierce conflict, most of the groundhogs are hilariously indifferent to the fight itself; instead, they are focused on protecting their soup bowls and continuing to eat—until they are ultimately hunted down and captured.

Nezha and the clan of groundhogs.

Besides fueling the social media meme machine, the groundhog scene actually also sparked discussions about social class and struggle. Some commentators began asking, “Are we Ne Zha or the groundhogs?”

Several blogs, including this one, argued that while many Chinese netizens like to identify with Nezha, they are actually more like the groundhogs; they don’t have powerful connections nor super talents. Instead, they are hardworking, ordinary beings, struggling to survive as background figures, positioned at the bottom of the hierarchy.

One comment from a film review captured this sentiment: “At first, I thought I was Nezha—turns out, I’m just a groundhog” (“开局我以为自己是哪咤,结果我是土拨鼠”).

The critical comparisons between Nezha and the groundhogs became politically sensitive when a now-censored article by the WeChat account Fifth Two-Six District (第五二六区) suggested that many Chinese people are so caught in their own information bubbles and mental frameworks that they fail to grasp how the rest of the world operates. The article said: “The greatest irony is that many people think they are Nezha—when in reality, they’re not even the groundhogs.”

While some see a parallel between Nezha’s struggles and their own hardships, others interpret the film’s success as a symbol of China’s rise on the global stage—particularly because the story is so deeply rooted in Chinese culture, literature, and mythology. This has led to an alternative perspective: rather than remaining powerless like the groundhogs, perhaps China—and its people—are transforming into the strong and rebellious Nezha, taking control of their destiny and rising as a global force.

Far-fetched or not, it’s an idea that continues to surface online, along with many other detailed analyses of the film. The nationalist Chinese social media blogger “A Bad Potato” (@一个坏土豆) recently wrote in a Weibo post:

“We were once the groundhog, but today, nobody can make us kneel!” (“我们曾经是土拨鼠,但是今天,没有任何人可以让我们跪下!”)

In another post, the blogger even dragged the Russia-Ukraine war into the discussion, arguing that caring too much about the powerless “groundhogs,” those struggling to survive, does not serve China’s interest. He wrote:

“(..) whether Russia is righteous or evil does not concern me at all. I only care about whether it benefits our great rejuvenation—whoever serves our interests, I support. Only the “traitors” speak hypocritically about love and justice. Speaking about freedom and democracy that we don’t even understand, they wish Russia collapses tomorrow but don’t care if that would lead to us being surrounded by NATO. So, in the end—are we Ne Zha, or are we the groundhog?”

One line from the film that has gained widespread popularity is: “If there is no path ahead, I will carve one out myself!” (“若前方无路,我就踏出一条路!”). Unlike the more controversial groundhog symbolism, this phrase resonates with many as a reflection not only of Nezha’s resilience but also of the determination that has been driving China’s animation industry forward.

The story of Ne Zha 2 goes beyond box office numbers—it represents the global success of Chinese animation, a revival of its golden era, and China’s growing cultural influence. Yet, paradoxically, it’s also all about the numbers. While the vast majority of its earnings come from the domestic market, Ne Zha 2 is still officially a global number-one hit. More than its actual reach worldwide, what truly matters in the eyes of many is that a Chinese animation has managed to surpass the US and Japan at the box office.

While the industry still has room to grow and many markets to conquer, this milestone proves that part of the Chinese animation dream has already come true. And with Ne Zha 3 set for release in 2028, the journey is far from over.

Want to read more on Ne Zha 2? Also check out the Ne Zha 2 buzz article by Wendy Huang here and our related Weibo word of the week here.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Some of the research referenced in this text can also be found in an article I published in 2019: The Chinese Animation Dream: Making Made-in-China ‘Donghua’ Great Again. For further reading, see:

►Du, Daisy Yan. 2019. Animated Encounters: Transnational Movements of Chinese Animation, 1940s-1970s. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

►Lent, John A. and Xu Ying. 2013. “Chinese Animation: A Historical and Contemporary Analysis.” Journal of Asian Pacific Communication 23(1): 19-40.

►Saito, Asako P. 2017. “Moe and Internet Memes: The Resistance and Accommodation of Japanese Popular Culture in China.” Cultural Studies Review 23(1), 136-150.

🌟 Attention!

For 11 years, What’s on Weibo has remained a fully independent platform, driven by my passion and the dedication of a small team to provide a window into China’s digital culture and online trends. In 2023, we introduced a soft paywall to ensure the site’s sustainability. I’m incredibly grateful to our loyal readers who have subscribed since then—your support has been invaluable.

But to keep What’s on Weibo thriving, we need more subscribers. If you appreciate our content and value independent China research, please consider subscribing. Your support makes all the difference.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China ACG Culture

“Black Myth: Wukong”: From Gaming Screens to the CMG Spring Festival Gala?

Published

3 months agoon

January 21, 2025

FROM THE WEIBO WATCH PREMIUM NEWSLETTER

Is Chinese game sensation ‘Black Myth Wukong’ making a jump from gaming screens to the CMG Spring Festival Gala? There’s already some online excitement over a potential performance at the biggest liveshow of the year.

The countdown to the most-watched show of the year has begun. On January 29, the Year of the Snake will be celebrated across China, and as always, the CMG Spring Festival Gala, broadcast on CCTV1, will air on the night leading up to midnight on January 28.

Rehearsals for the show began last week, sparking rumors and discussions about the must-watch performances this year. Soon, the hashtag “Black Myth: Wukong – From New Year’s Gala to Spring Festival Gala” (#黑神话悟空从跨晚到春晚#) became a topic of discussion on Weibo, following rumors that the Gala will feature a performance based on the hugely popular game Black Myth: Wukong.

Three weeks ago, a 16-minute-long Black Myth: Wukong performance already was a major highlight of Bilibili’s 2024 New Year’s Gala (B站跨年晚会). The show featured stunning visuals from the game, anime-inspired elements, special effects, spectacular stage design, and live song-and-dance performances. It was such a hit that many viewers said it brought them to tears. You can watch that show on YouTube here.

While it’s unlikely that the entire 16-minute performance will be included in the Spring Festival Gala (it’s a long 4-hour show but maintains a very fast pace), it seems highly possible that a highlight segment of the performance could make its way to the show.

Recently, Black Myth: Wukong was crowned 2024’s Game of the Year at the Steam Awards. The game is nothing short of a sensation. Officially released on August 20, 2024, it topped the international gaming platform Steam’s “Most Played” list within hours of its launch. Developed by Game Science, a studio founded by former Tencent employees, Black Myth: Wukong draws inspiration from the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West. This legendary tale of heroes and demons follows the supernatural monkey Sun Wukong as he accompanies the Tang Dynasty monk Xuanzang on a pilgrimage to India to retrieve Buddhist scriptures. The game, however, focuses on Sun Wukong’s story after this iconic journey.

The success of Black Myth: Wukong cannot be overstated—I’ve also not seen a Chinese video game be this hugely popular on social media over the past decade. Beyond being a blockbuster game it is now widely regarded as an impactful Chinese pop cultural export that showcases Chinese culture, history, and traditions. Its massive success has made anything associated with it go viral—for example, a merchandise collaboration with Luckin Coffee sold out instantly.

If Black Myth: Wukong does indeed become part of the Spring Festival Gala, it will likely be one of the most talked-about and celebrated segments of the show. If it does not come on, which we would be a shame, we can still see a Black Myth performance at the pre-recorded Fujian Spring Festival Gala, which will air on January 29.

Lastly, if you’re not into video games and not that interested in watching the show, I still highly recommend that you check out the game’s music. You can find it on Spotify (link to album). It will also give you a sense of the unique beauty of Black Myth: Wukong that you might appreciate—I certainly do.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

No Quiet Qingming: From High-Tech Tomb-Sweeping to IShowSpeed & the Seven China Streams

From Trade Crisis to Patriotic Push: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Tariffs

China Trending Week 14: Gucci Fake Lipstick, Xiaomi SU7 Crash, Yoon’s Impeachment

Strange Encounter During IShowSpeed’s Chengdu Livestream

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Beyond the Box Office: What’s Behind Ne Zha 2’s Success?

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

15 Years of Weibo: The Evolution of China’s Social Media Giant

Tuning Into the Year of the Snake

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

TikTok Refugees, Xiaohongshu, and the Letters from Li Hua

The ‘China-chic Girl’ Image and the Realities of China’s Competitive Food Delivery Market

“Black Myth: Wukong”: From Gaming Screens to the CMG Spring Festival Gala?

US-Russia Rapprochement and “Saint Zelensky”: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Shake-Up

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight11 months ago

China Insight11 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

-

China Arts & Entertainment11 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment11 months agoSinging Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Angelique Wu

August 16, 2022 at 12:28 pm

I don’t think you fairly represented the opinions of the Chinese people, nor did you fairly report the our side’s concerns.

In my opinion, choosing to wear Japanese traditional clothing is your own freedom.

The main issue is that the date she chose is far too sensitive.

Is the date of Japan’s unconditional surrender really the best day to do it? Is she really just unaware of the history? Or is she one of those people who, because she likes Japan’s anime and manga, will make out Japan’s historical crimes as less serious than they are? There’s already a major issue in China where people 崇洋内外 (you claim to be a “Sinologist”, you should know this), and that just piles on more shit to this pile of crap.

Does she feel no guilt for our compatriots who were brutally killed, the ancestors of our people who suffered so much, and the family members of the victims?

Many Chinese, especially Chinese people of that police uncle’s age, personally knew victims of the Japanese. If the police uncle had a grandfather who had his entire family murdered and raped by the Japanese, if the police uncle had a grandmother who survived through the Nanjing Massacre as a small child but had her entire family killed and became deaf because a Japanese soldier hit her on the head (real story by the way), don’t you think it’s understandable that he reacted the way he did?

All Chinese have heard of the terrible stories that happened to their family, and they’ve heard of other ones too. A family of 100+ people, with only 2 small children surviving. An entire generation in Nanjing, basically wiped out. Mass enslavement of Northeasterners, who were literally worked to death like cattle. Horrendous rapes, human experiments, and torture methods.

Especially since at the time, one of Japan’s goals was to annihilate Chinese cultural identity by murdering, enslaving, and torturing people. They wanted to turn us into Japanese people. Our ancestors used their blood and blood to help us block that knife, and now, disregarding their sacrifice, that girl is willingly wearing Japanese traditional clothing.

Personally, I would never, but as I said before, I do think it’s her own choice. However, the date is far too sensitive, and the history is still too alive for many people. Just like how a Jewish person who survived the Holocaust would understandably subconsciously tremble when hearing the German language due to trauma, so too do the Chinese have similar reactions towards Japanese things.

Sure, she can choose to wear Japanese clothing, that’s her freedom; but likewise, she should understand that the repercussions of her actions are also other people’s freedom.

Just like how people can say and do whatever evil shit they like to others, but they shouldn’t be surprised if they get punched.

I’ve talked to multiple Chinese people, even those in the 2D community, and they all agreed with me. Liking anime is not an excuse to excuse and forget the murder, torture, and rape of your ancestors and compatriots.

Xyz

August 16, 2022 at 2:42 pm

This is shameful. Even behaving like that with a woman just for cosplaying.

Hector Pritt

August 19, 2022 at 7:03 am

She was wearing a cosplay from a comic book for crying out loud, not a Japanese military uniform. The terrible history of Japan in China happened pre-WW2. The young generation of today of both countries are not in any way responsible for that event. Your sentiment is borderline racist against the Japanese. Being offended by these little things because they relate to another country that committed atrocities last century and holding grudges is not the path to healing. Unless the woman was purposefully trying to be offensive, which is highly doubtful, that still doesn’t excuse the kind of racist behavior the policeman exhibited towards fashion he didn’t like. If we want to talk about atrocities, there are more recent and current ones committed by the Chinese government.

J Huang

November 1, 2023 at 4:24 am

@Angelique Wu “don’t you think it’s understandable he reacted the way he did?” No I think it’s 1) not understandable and 2) extremely unreasonable for him to act the way he did. He’s a police officer, this is blatant abuse of power. He needs to have better self-control or not be a police officer. Do you think anyone else visiting a street famed for it’s Japanese restaurants and culture give a shit? The officer is a petty thuggish bully. “she should understand that the repercussions of her actions are also other people’s freedom” And you are a victim blamer. Is it other people’s freedom to manhandle her and grab her and take her away for detainment because they are offended? If the answer is no, then why is it OK for the police officer to abuse his power to manhandle and detain her because he is offended? She is NOT doing anything ILLEGAL, only morally distasteful. Police must enforce the law, not their personal morals. As persons with the authority of the State invested in him, police must act with highest moral character and strict adherence to law and duty. He is disgraceful and so are you for defending him.