China Arts & Entertainment

Top 30 Classic TV Dramas in China: The Best Chinese Series of All Time

This year marks 60 years of Chinese TV drama. These are the best Chinese TV dramas of all time.

Published

6 years agoon

PREMIUM CONTENT ARTICLE

First published

They might have aired 30 years ago, but some TV dramas just never get old. We have listed the greatest classic Chinese TV dramas of all time, that, either because of their high-production value or historic ratings, are still talked about today. A special overview by What’s on Weibo, as China celebrates 60 years of TV drama this year.

This year marks the 60th anniversary of Chinese TV drama since the airing of the very first (one-episode) drama A Mouthful of Vegetable Pancakes (一口菜饼子) in 1958 – the same year in which the very first Chinese television station started broadcasting (Bai 2007, 77).

The drama, live broadcasted by Beijing Television, sent out a message of frugality, as one young girl warns her sister not to waste food by remembering her of their difficult past and brave mother, who died of hunger while even refusing to eat the last bit of food, a vegetable pancake.

A Mouthful of Pancakes aired in 1958.

Much has changed within those sixty years. After a time when the production of TV dramas practically came to a standstill during the Cultural Revolution, the late 1970s and early 1980s saw a boom in the popularity of television dramas, along with a spike in households that owned their own TV. From 1980 to 1990, the number of household television sets in China increased from 5 to 160 million (Wang & Singhal 1992, 177).

Since the 1980s, mainland China has gone from a country where most television dramas were imported from outside the country, to one that has the most thriving domestic TV drama industry in the world.

Some TV dramas in this list have become classics through time, some are fairly new but have already become classics within their genre.

This list has been fully compiled by What’s on Weibo, based on popularity charts on Chinese search engine Sogou’s top tv drama listings of all time, together with ranking on Douban, a big Chinese social networking service and influential media review website, and also based on academic sources that note the importance of some of these TV classics.*1 We will list a recommendation list of relevant books at the end of this article.

Most of these series will have links redirecting to available versions on Youtube or elsewhere – unless written otherwise, they do not have English subtitles. Please share English subtitled versions in the comment section if you found them, we’ll add them to the list.

This article is focused on those classics that have been important for the TV drama industry and audiences of mainland China. Although several of them were produced in Hong Kong or Taiwan, the majority is from the PRC. These dramas are listed in chronological order of appearance, not listed based on rankings.

Here we go!

#1 The Bund / The Shanghai Bund (上海滩)

Year: 1980

Episodes: 25

Genre: Action

Produced in Hong Kong

Noteworthy: “The Godfather of the East”

This TV drama became such a sensation across China in 1980, that it also became known as the Chinese equivalent to the classic Godfather series.

Actors Angie Chiu and Chow Yun-Fat star in this Hong Kong drama, that is set in the underworld society of 1920s Shanghai, and revolves around the tumultuous love story between Feng Chengcheng and Xu Wenqiang.

The series has become such a classic that it still plays an important role in popular culture of China today, with newer films and TV dramas also being based on the original series (the 2007 mainland China TV series Shanghai Bund, for example, is a remake of the 1980 original). If you ever go to karaoke, you’re probably already familiar with the shows’ famous theme song ‘Seung Hoi Tan’ (上海滩) by Frances Yip (see here).

#2 Eighteen Years in the Enemy’s Camp (敌营十八年)

Year: 1981

Episodes: 9

Genre: War Drama

Watch the first episode here on Youtube.

Noteworthy: “The first TV drama produced by CCTV”

Eighteen Years in the Enemy’s Camp is somewhat of a cult classic in China. Despite the fact that the TV drama itself was somewhat poorly produced, it still gets high ratings on sites such as QQ Video or Douban today.

At a time when the Chinese TV drama market was still dominated by imported television series (from Hong Kong, US, and other places), Eighteen Years in the Enemy’s Camp was the first drama series made by CCTV (Bai 2007, 80), directed by Wang Fulin (王扶林) and Du Yu (都郁).

The story revolves around the Communist Party member Jiang Bo (江波), who spends 18 years undercover in the “tiger’s den” (虎穴), the enemy’s camp, as a National Army officer, thwarting the Nationalists’ plans until the 1949 victory of the Communists.

Fun fact by Ruoyun Bai (see references): despite the fact that the entire show is about the Nationalists Army, not a single Nationalist Army uniform could be found for the cast. The uniforms that were used, were not up to par: the main character had to leave his coat’s collar unbuttoned because it was too tight, and always has his hat in his hands because it was actually too small to fit his head (2007, 80-81).

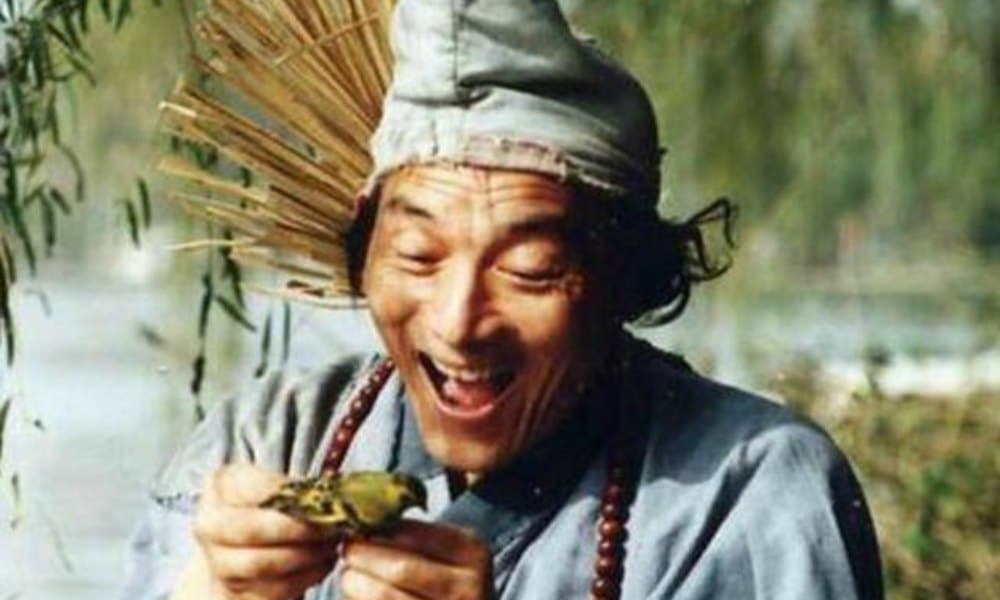

#3 Ji Gong (济公)

Year: 1985

Episodes: 12

Genre: Fantasy

Directed by Zhang Ge (张戈)

All episodes can be watched here on YouTube.

Noteworthy: “Influenced by Charlie Chaplin”

This popular TV series is centered around Ji Gong, the folk hero and Chan Buddhist monk who lived in the Southern Song and, according to legend, had supernatural powers and spent his whole life helping the poor.

The main role is played by renowned Chinese artist and mime master You Benchang (游本昌). In an interview with CRI, the actor once said that he was heavily influenced by his idol Charlie Chaplin for this role, sometimes even imitating some of Chaplin’s gestures.

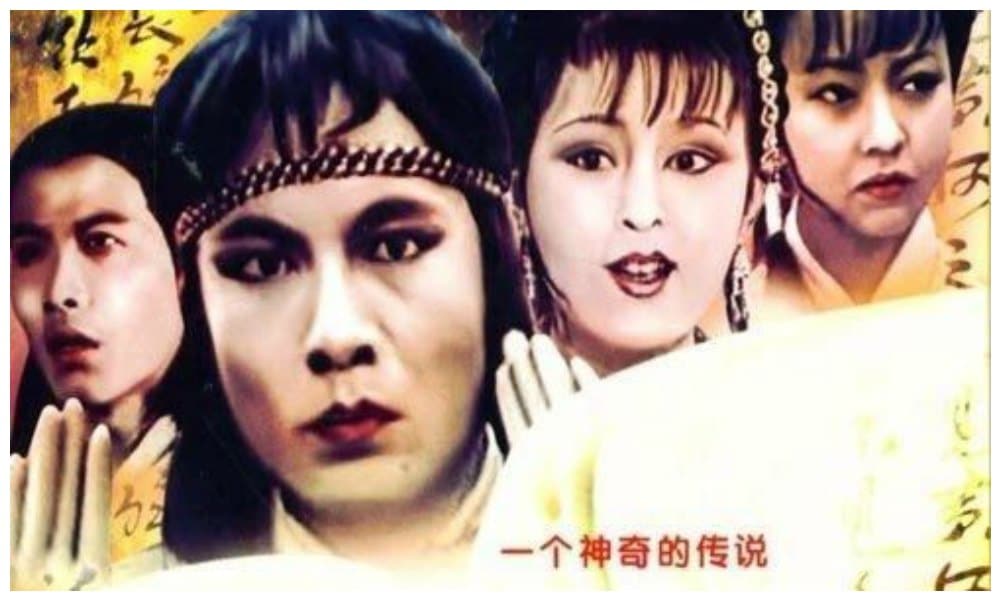

#4 Chronicles of The Shadow Swordsman (萍踪侠影)

Year: 1985

Episodes: 25

Genre: Wuxia/Martial

Directed by: Wang Xinwei (王心慰)

Produced in Hong Kong

Episodes available on Youtube here.

Noteworthy: “Perfect Chemistry between Leading Actors”

This classic TV drama features actors Damian Lau as Zhang Danfeng and Michelle Yim as Yun Lei, whom are often praised by drama lovers for their perfect chemistry in these series. Of the many adaptations there are of Liang Yusheng’s wuxia novel Chronicles of The Shadow Swordsman, many say this is their favorite.

#5 New Star (新星)

Year: 1986

Episodes: 12

Directed by: Li Xin (李新)

Noteworthy: “A drama anyone over 50 will remember”

This CCTV mini-drama, based on the novel by Ke Yunlu (柯云路), tells the story of a young Party secretary fighting against corruption. Before Heaven Above (later in this list), it is thus one of the very first dramas to focus on corruption as a theme, and it also caused a buzz at the time for doing so – most people over 50 in China today will probably remember this TV series today.

#6 Journey to the West (西游记)

Year: 1986

Episodes: 25 for season one, 16 episodes for season 2

Directed by Yang Jie (杨洁)

Watch on Youtube (with English subtitles!) here.

Noteworthy: “Shot with one camera”

This is an all-time favorite TV series in China that is still rated with a 9.5 on the TV drama database of search engine Sogou. It has been an instant classic from the moment it was first broadcasted by CCTV in October of 1986.

Journey to the West (Xīyóu jì 西游记), published in the 16th century (Ming dynasty), is one of the most important classical works in the history of Chinese literature, and tells the story of the long journey to India of the Tang Monk Xuánzàng, who is on a mission to obtain Buddhist sutras. He is joined by three disciples, the pig demon Zhū Bājiè, the river demon Shā Wùjìng, and Sūn Wùkōng, who is better known as the Monkey King in the West.

The Monkey in the series is played by Zhang Jinlai (章金莱), also known as Liu Xiao Ling Tong, who recently recalled in an CGTN article that: “it was 30 years ago and we’d got only one camera. We walked around China’s picturesque areas and took 17 years to make 41 episodes. 17 years equals Monk Xuanzang’s pilgrimage for the Buddhist scriptures.”

#7 “The Dream of Red Chambers” (红楼梦)

Year: 1987

Episodes: 36

Directed by: Wang Fulin (王扶林)

Watch with English subtitles on YouTube here.

Noteworthy: “The first entry of Chinese tv drama into the global market”

Even today, this CCTV TV series from 1987 is still rated as one of the best Chinese television series of all time on Sogou, where viewers rate it with a 9.6.

Like other series in this list, this is an adaptation from a classic literary work; Dream of the Red Chamber (Hónglóumèng), one of China’s Four Great Classical Novels, which was written by Cao Xueqin in the mid-18th century during the Qing.

In June of 1987, this TV drama became the first Chinese television series to be exported to Malaysia and West-Germany, making it “the first entry of Chinese tv drama into the global market” (Hong, 32).

#8 The Investiture of the Gods (封神榜)

Year: 1990

Episodes: 36

Genre: Fantasy/Costume Drama

Directed by: Guo Xinling (郭信玲)

The first episode is available on YouTube here.

Noteworthy: “Based on the classical novel Fengshen Yanyi“

This TV series is based on the classical novel Fēngshén Yǎnyì (封神演義), also known as Investiture of the Gods or Creation of the Gods), written by Xu Zhonglin and Lu Xixing. Famous Chinese actor and painter Lan Tianye (蓝天野) was praised for his role as Jiang Ziya in this drama.

The (female) director Guo Xinling (1936-2012) was a Party member who worked on many televised works during her career.

Just as many others of the series in this list based on classic novels, there are remakes of these series in recent times.

#9 Yearnings / Kewang (渴望)

Year: 1990

Episodes: 50

Genre: Family drama

Directed by Lu Xiaowei (鲁晓威) and Zhao Baoguang (赵宝刚).

Noteworthy: “China’s first soap opera – a national craze”

Yearnings is also known as China’s real first soap opera, which caused a sensation across the nation – sales of TV sets surged, and streets were empty when it aired.

The story’s time spans from the Cultural Revolution until the 1980s reform period. The series, set in Beijing, tells the story of working-class woman Liu Huifang and her unlikely marriage to the middle-class Wang Husheng, a university graduate who comes from a family of intellectuals. When Huifang finds an abandoned baby, she adopts it against the will of her husband.

As the first TV series that focused on the hopes and dreams of ordinary Chinese people, the success of Yearnings was unprecedented, and it formed the beginning of Chinese television drama as we know it today.

#10 River of Gratitude (江湖恩仇录)

Year: 1989

Episodes: 20

Genre: Wuxia/Martial

Directed by: Mao Yuqin (毛玉勤)

Watch first episode on Youtube here

Noteworthy: “A true classic – it’s nostalgia!”

One of the main stars in this series is actress and producer Wenying Dongfang (东方闻樱), who also starred in A Dream in Red Mansion (1987).

By commenters on Douban, this series is described as a “cult classic.” Although some say the quality of the series, now, looking back, is somewhat substandard or silly, according to many, the nostalgia of seeing it in the early 1990s and being excited about it seems to play a major factor in why people still grade this one as a true classic – it’s nostalgia!

#11 Wan Chun (婉君)

Year: 1990

Episodes: 18

Produced in Taiwan

Noteworthy: “The first Taiwanese TV series filmed in mainland China”

Wan Chun is a 1990 Taiwanese television series about a girl named Wan Chun and her three adoptive brothers, that is based on the 1964 novel “Wan-chun’s Three Loves” (追尋) by Taiwanese writer and producer Chiung Yao, and which is set in Republican era Beijing.

This is the first cross-strait co-production, as a Taiwanese TV series filmed in mainland China. Wan Chun was followed up by the 1990 Taiwanese television drama series Mute Wife based on Chiung Yao’s 1965 novelette of the same name.

#12 The Legend of Qianlong (戏说乾隆)

Year: 1991

Episodes: 41

Genre: Imperial drama

Produced in Taiwan (Taiwan-mainland co-production)

Watch on Youtube here

Noteworthy: “The beginning of a genre”

In today’s TV drama environment of China, dramas that focus on life during the imperial era are ubiquitous, with titles from the Imperial Doctress to Story of Yanxi Palace being everywhere.

But when this drama aired in the early 1990s, it was something quite new. The Legend of Qianlong, also known with the English translation A Fanciful Account of Qianlong, tells the (fictional) stories of the Emperor Qianlong’s Tours of Southern China.

It was the beginning of a drama genre that turned out to be hugely popular, with many new television series focusing on emperors and empresses in their youth or their tumultuous lives during the height of their power (Barme 2012, 33). Perhaps, this 1991 series will always be a classic just because it was one of the first within its genre.

#13 The Legend of the White Snake (新白娘子传奇)

Year: 1992

Episodes: 50

Genre: Fantasy

Produced in Taiwan

Noteworthy: “One of the most replayed TV series”

As many of the classics in this list, this hit TV series is also based on a folk legend, namely that of Madame White Snakee, a mythical snake-like spirit who strives to be human, which is a source for many major Chinese operas, films.

The 1992 TV series stars Angie Chiu and Cecilia Yip. In 2016, it was still one of the most replayed TV series. Even on IMDB, it is rated with an 8.2.

#14 Beijinger in New York (北京人在纽约)

Year: 1993

Episodes: 21

Watch: YouTube

Buy novel (in English): Beijinger in New York

Noteworthy: “The first Chinese-language TV show to be shot in the United States”

The TV series Beijinger in New York, also known as A Native of Beijing in New York, based on the novel by Glen Cao (Cao Guilin), was a hit when it was first broadcasted broadcast nightly on CCTV and watched by millions of Chinese.

The story follows the immigrant life of cello player and Beijinger Wang Qiming (王起明), who arrives in New York in 1980 together with his wife, and begins working as a dishwasher the next day.

The TV series marks a first in several aspects. It was the first Chinese-language TV show to be shot in the United States, but it was also the first time ever for the production of a Chinese TV drama that a bank loan was used in order to make it possible (Bai 2007, 83); in other words, it also marks the start of a more commercialized TV drama environment. FYI: the bank loan that was used was a total of US$1.3 million.

#15 I Love My Family (我爱我家)

Year: 1993

Genre: Comedy

Episodes: 120

Directed by Ying Da (英达) et al

First episodes on Youtube here.

Noteworthy: “First Mandarin-language sitcom”

I Love My Family (Wǒ ài wǒjiā) is one of China’s first popular sitcoms, and the first Mandarin-language and multi-camera sitcom, that aired from 1993 to 1994. It has since been rerun on local channels countless of times.

One of the show’s central stars is Wen Xingyu (文兴宇), who was a popular comedian and director in mainland China.

At the time of I Love My Family, sitcoms were mostly characterized by their low production cost; three episodes were made within five working days (Di 2008, 122).

#16 Justice Pao (包青天)

Year: 1993

Episodes: 236

Genre: Historical drama

Produced in Taiwan

Some episodes on Youtube here.

Noteworthy: “From 15 to 236 episodes”

This series is themed around Bao Zheng (包拯), a government official who lived during China’s Song Dynasty, from 999 to 1062, and who was known for his extreme honesty and uprightness. Award-winning Taiwanese actor Jin Chao-chun (金超群) plays this role.

The series was originally scheduled for just 15 episodes, but was received so well when it aired on Chinese Television System, that it was eventually expanded to 236 episodes.

The story of Justice Bao is still a recurring topic in the popular culture of mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. There was the 2008 Chinese series Justice Bao, and the 2010 New Justice Bao, that also starred Jin Chao-chun.

#17 Romance of the Three Kingdoms (三国演义)

Year: 1994

Episodes: 84

Genre: Historical drama

Directed by: Wang Fulin (王扶林)

Buy original novel here: The Romance of the Three Kingdoms

Some episodes available with English subtitles here.

Noteworthy: “400,000 people involved in the production”

This is another classic TV series produced by the CCTV, and that is also adapted from a classical novel (same title, written by Luo Guanzhong). Its director, Wang Fulin (王扶林), also directed the CCTV’s first TV drama Eighteen Years in the Enemy’s Camp, and A Dream of Red Mansions.

The production of Romance of the Three Kingdoms is especially noteworthy because the productions costs broke all kinds of records at the time; the production of the 84 one-hour episodes took four years, total costs were over 170 million RMB (±US$25 million), and around 400,000 people were involved – the larghest number of people involved in a production in the history of Chinese television. THe show has been watched by some 1,2 billion people around the world (Hongb 2007, 127).

#18 Heaven’s Above (苍天在上)

Year: 1995

Episodes: 17

Genre: Corruption drama (or ‘anti-corruption drama’ 反腐剧)

Directed by: Zhou Huan (周寰)

Noteworthy: “First drama about high-level official corruption”

In late 1995, the CCTV drama Heaven Above (Cāngtiān zài shàng) debuted on Chinese TV as the first TV series about high-level official corruption in the PRC.

It would certainly not be the last, as ‘corruption dramas’ became wildly popular – it is the entire focus of the 2014 book Staging Corruption by scholar Ruoyun Bai.

#19 Foreign Babes in Beijing (洋妞在北京)

Year: 1995

Genre: Urban drama

Episodes: 20

Noteworthy: “Foreign women in Chinese dramas”

Foreign Babes in Beijing (Yáng niū zài Běijīng) was one of the new kinds of dramas that featured foreigners in China. This series focues on two Chinese men and two American women, of which one seduces one of the Chinese (married) men. The show was a big hit in the mid-1990s.

One of the show’s actresses, Rachel Dewoskin, later wrote the recommended book Foreign Babes in Beijing: Behind the Scenes of a New China about her experiences of playing in the show and her life in China at the time.

#20 My Dear Motherland (我亲爱的祖国)

Year: 1999

Episodes: 21

Genre: History/War

Directed by: Liu Yiran (刘毅然)

Watch on Billibilli here, QQ, or on Youtube.

Noteworthy: “Rated with a 9.1”

This 1999 series is still rated with a 9.1 on Douban today. The series tells the experiences and hardships of three generations of Chinese intellectuals during the tumultuous (war)history of China’s 20th century, starting during the May Fourth Movement in 1919.

Chen Jianbin (陈建斌) is one of the famous actors starring in this TV drama as Fang Xuetong.

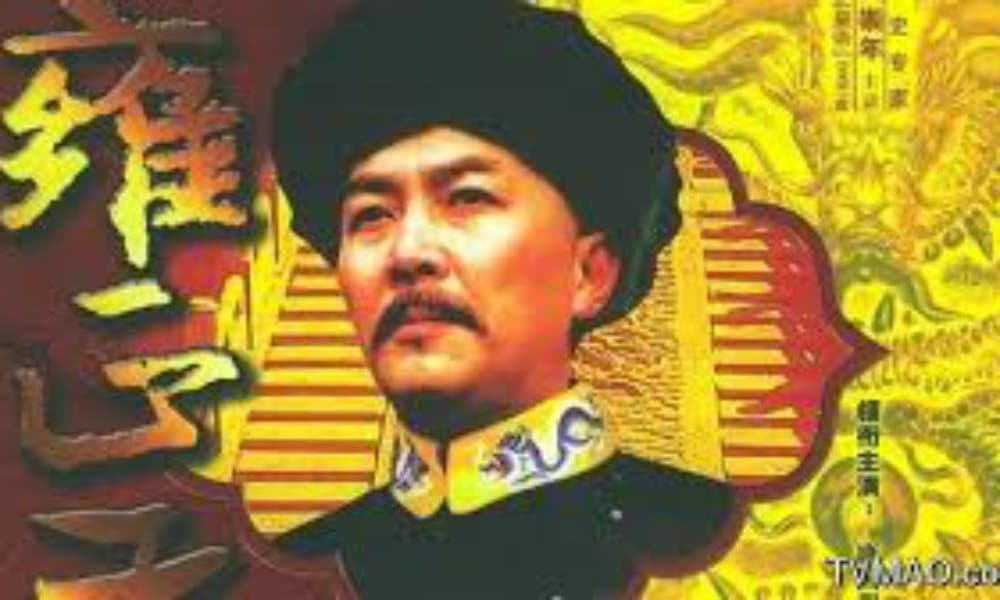

#21 Yongzheng’s Dynasty (雍正王朝)

Year: 1999

Episodes: 44

Genre: History/Costume

Noteworthy: “Qing drama as export product”

Yongzheng Dynasty is one of many so-called “Qing dramas” – TV dramas that focus on palace life during the 1644-1911 Qing Dynasty. According to scholar Zhu (2008), one of the reasons that dynasty dramas such as these became so enormously popular in mainland China is that (1) certain social and political issues can be discussed in the shape of stories and settings that are very much removed from modern-day China, allowing for more relaxed censorship policies on storylines and dialogues, and (2) that the reconstruction of “history” allows room for artistic interventions (22).

This epic TV drama was loosely based on historical events in the reigns of the Kangxi and Yongzheng Emperors, and became one of the most watched television series in mainland China of the 1990s. Also outside of China the show became very popular, making the so-called ‘Qing dramas’ an export product.

#22 Towards the Republic (走向共和)

Year: 2003

Episodes: 59 (one hour per episode)

Genre: Historical drama

Directed by: Zhang Li (张黎)

Watch on Youtube , buy on Amazon with English subtitles.

Noteworthy: “59 hours of historical drama”

This is one of the most important TV series in this list. On Sogou ratings, Towards the Republic, which is also known as For the Sake of the Republic (Zǒuxiàng gònghé), is one of netizens’ top all-time favorite series, rated with a 9.7.

The CCTV TV drama tells the story of the historical events in China from 1890 to 1917 – the time during which the Qing Dynasty collapsed, and the Republic of China (1912-1949) was founded. Important historical events such as the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), the Hundred Days’ Reform (1898), the Boxer Rebellion (1900) and the Xinhai Revolution (1911) are all featured in this epic drama, that mainly focuses on the lives of Li Hongzhang (Chinese general in late Qing), Empress Dowager Cixi, Sun Yat-Sen, and Yuan Shikai.

The historical drama was not without controversy, and some parts of it have been censored in mainland China. The original series had 60 episodes, which was later brought down to 59. The TV drama has also been a fruitful topic for scholars for its representation of history. In the 2007 book Representing History in Chinese Media: The TV Drama Zou Xiang Gonghe (Towards the Republic) by Gotelind Mueller, the entire series is analyzed in how history is portrayed and narrated.

#23 Crimson Romance (血色浪漫)

Year: 2004

Episodes: 32

Genre Youth drama

Directed by: Teng Wenji (滕文骥)

Watch on Youtube here.

Noteworthy: “Romantizing the Cultural Revolution”

There are almost 40,000 netizens ranking this 2004 TV drama on Douban, where it scores a 8.7.

The TV drama, which is also known as Romantic Life in English, dramatizes memories of the Cultural Revolution, focusing on a group of friends, their hopes and dreams, and their romantic life. It is set in Beijing in the late period of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976).

#24 Fu Gui (福贵)

Year: 2005

Episodes: 33

Genre: Family drama

Directed by Zhu Zheng (朱正)

Original novel: To Live: A Novel

Watch on Youtube.

Noteworthy: “Based on the novel To Live“

Chuang Chen (陈创), Liu Mintao (刘敏涛), and Li Ding (李丁) star in this family drama, which is ranked with a 9.4 on Sogou, and 4,5 stars or a 9,4 on Douban (more than 5500 voters).

The drama is based on the 1993 novel by Yu Hua (余华) To Live (活着), which focuses on the struggles of the son of a wealthy land-owner, Xu Fugui, amidst the tumultuous times of the Chinese Revolution. The story became well-known by the movie of the same title by Zhang Yimou, which became an international success.

#25 Ming Dynasty in 1566 (大明王朝1566)

Year: 2007

Episodes: 46

Genre: Historical drama

Directed by: Zhang Li (张黎)

Available with English subtitles on Youtube

Noteworthy: “Scoring a 9.7 on Douban, rated by 55,000 users”

Ming Dynasty in 1566 (Dàmíng wángcháo), starring Chinese actor Chen Baoguo (陈宝国), is a Chinese television series based on historical events during the reign of the Jiajing Emperor (1507-1567) of the Ming dynasty. It was first broadcast on Hunan TV in China in 2007.

On Douban, more than 55000 people have reviewed this movie at time of writing, coming up with a score of 9.7, one of the highest in this list. The drama was also broadcasted in other countries, such as South Korea.

#26 Dwelling Narrowness (蜗居)

Year: 2009

Episodes: 35

Genre: Urban Drama

Directed by: Teng Huatao (滕华涛)

Watch on Youtube here.

Noteworthy: “Focusing on China’s urban real estate bubble”

Also known as Snail House, this TV drama was all the rage back in 2009 for its focus on the crazy housing market in urban China and the lives of ordinary Chinese who are struggling to survive in the city while living in small spaces. Dwelling Narrowness, based on a novel by the same name, tells the story of two sisters with very different lifestyles who are looking to find a home in Shanghai (or actually, the fictional city of Jiangzhou, that basically represents Shanghai), and improve their quality of life, each in their own way.

The real estate bubble is a major theme throughout these series, and the TV drama was much-discussed within the frame of Chinese urban dwellers becoming “house slaves” (房奴). In the year of its broadcast, Wall Street Journal featured an article dedicated to the series and the discussions it triggered online.

#27 The Red (红色)

Year: 2014

Episodes: 48

Genre: War drama

Directed by Yang Lei (杨磊)

Noteworthy: “Patriotism as its key theme”

War drama The Red (Hóngsè) receives a 9.2 on Sogou, showing its success over the last four years.

Edward Zhang (Zhang Luyi 张鲁一) stars in this drama as an ordinary worker in Shanghai who gets caught up in underground circles at the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War, and unexpectedly becomes part of a decisive moment in Chinese modern history. Perhaps unsurprinsginly, ‘Patriotism’ is a key theme throughout The Red.

#28 Moral Peanuts – Final Season (毛骗 终结篇)

Year: 2015

Episodes: 10 (in this season)

Genre: Crime/Suspense

Directed by: Li Hongchou (李洪绸)

Watch on Youtube here.

Noteworthy: “A gang of friends who con people out of their money”

Rated with a 9.6 on Sogou and a 9.6 by more than 26,000 people on Douban, this TV drama has already become somewhat of a classic in the few years since its airing.

Moral Peanuts is a multiple season series (started in 2010), that follows a gang of five young friends who live together and earn their living in a fraudulent way. The series is characterized by its cliffhanger endings and its ‘grey’ portrayals of its characters.

#29 In the Name of the People (人民的名义)

Year: 2017

Episodes: 55

Genre: Corruption drama

Directed by: Li Lu

Available with English subtitles here.

Noteworthy: “The Chinese ‘House of Cards'”

In the Name of the People is a 2017 highly popular Chinese TV drama series based on the web novel of the same name by Zhou Meisen (周梅森). Its plot revolves around a prosecutor’s efforts to unearth corruption in a present-day fictional Chinese city by the name of Jingzhou.

In 2017, this TV drama became a true craze on Chinese social media and received a lot of coverage in (international) media for being comparable to the American political drama House of Cards. The BBC described it as “the latest piece of propaganda aimed at portraying the government’s victory in its anti-corruption campaign.”

#30 White Deer Plain (白鹿原)

Year: 2017

Genre: Contemporary historical drama

Episodes: 85

Directed by: Liu Jin (刘进)

WAtch with English subs at New Asian TV here.

Noteworthy: “The epic TV drama took nearly 17 years to prepare and produce “

This TV drama has consistently been ranking number one in Baidu’s and Weibo’s popular drama charts last year, and is now ranked with an 8.8 score on sites such as Douban. Although it is somewhat tricky to call such a present-day drama a ‘classic’, we’ll take the chance.

White Deer Plain is based on the award-winning Chinese literary classic by Chen Zhongshi (陈忠实) from 1993. The preparation and production of this series reportedly took a staggering 17 years and a budget of 230 million yuan (US$33.39 million).

The success of the novel this TV drama is based on, has previously been compared to that of One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez. White Deer Plain follows the stories of people from several generations living on the ‘White Deer Plain,’ or North China Plain in Shaanxi province, during the first half of the 20th century. This tumultuous period sees the Republican Period, the Japanese invasion, and the early days of the People’s Republic of China. The series is great in providing insights into how people used to live, from dress to daily life matter. The scenery and sets are beautiful.

Some Book Recommendations Based on This List:

* Chinese Television in the Twenty-First Century: Entertaining the Nation (Routledge Contemporary China Series Book 121)

* Staging Corruption: Chinese Television and Politics (Contemporary Chinese Studies)

* Television in Post-Reform China: Serial Dramas, Confucian Leadership and the Global Television Market (Routledge Media, Culture and Social Change in Asia)

* TV Drama in China (TransAsia: Screen Cultures)

* Media in China: Consumption, Content and Crisis

Want to know more? Check out our various Top 10s of popular Chinese TV Dramas from 2013 to present here.

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

*1(We kindly ask not to reproduce this list without permission – please link back if referring to it).

References

Bai, Ruoyun. 2007. “TV Dramas in China – Implications of the Globalization.” In Manfred Kops and Stefan Ollig (eds), Internationalization of the Chinese TV sector, 75-99. Berlin: LIT Verlag.

Bai, Ruoyun. 2014. Staging Corruption: Chinese Television and Politics. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Barmé, Geremie. 2012. “Red Allure and the Crimson Blindfold.” China Perspectives, 2012/2, 29-40.

Di, Miao. 2008. “A Brief History of Chinese Situation Comedies.” In Ruoyun Bai, Ying Zhu, Michael Keane (eds), TV Drama in China, 117-129. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Hong, Junhao. 2007. “The Historical Development of Program Exchange in the TV Sector.” In Manfred Kops and Stefan Ollig (eds), Internationalization of the Chinese TV sector, 25-40. Berlin: LIT Verlag.

–. 2007b. “From Three Kingdoms the Novel to Three Kingdoms the Television Series: Gains, Losses, and Implications.” In Kimberly Besio and Constantine Tung (eds), Three Kingdoms and Chinese Culture, 125-143. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Zhu, Ying. 2008. “Yongzheng Dynasty and Totalitarian Nostalgia.” In Bai R, Keane M, Zhu Y. (eds), TV Drama in China, 21-33. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press; 2008

Wang, Min and Arvind Singhal. 1992. “Kewang, A Chinese Television Soap Opera With A Message.” Gazette 49: 177-192.

Directly support Manya Koetse. By supporting this author you make future articles possible and help the maintenance and independence of this site. Donate directly through Paypal here. Also check out the What’s on Weibo donations page for donations through creditcard & WeChat and for more information.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2018 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Memes & Viral

Weibo Watch: Going the Wrong Way

About how one delivery driver’s plea for leniency shed light on challenges and struggles faced by millions of food delivery workers, and more must-know trends.

Published

3 weeks agoon

August 22, 2024

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #35

This week’s newsletter:

◼︎ 1. Editor’s Note – Going the wrong way

◼︎ 2. What’s New and Noteworthy – A closer look at featured stories

◼︎ 3. What’s Trending – Hot highlights

◼︎ 4. What’s Noteworthy – Young woman’s lonely death in rented apartment

◼︎ 6. What’s Popular – Fan Zhendong’s pluche toys

◼︎ 7. What’s Memorable – Ren Zhiqiang’s Weibo exit

◼︎ 8. Weibo Word of the Week – Fandom-ization

Dear Reader,

“Apology! Apology!” Dozens of delivery drivers chanted, standing together in front of Hangzhou’s Xixi Century Square. The group of workers, mostly men, had gathered in front of the complex after learning about an incident that took place just hours earlier.

One of their colleagues, a young delivery driver for the Meituan platform named Wang, had accidentally damaged a fence while trying to enter the complex to deliver a food order on August 12. The security guard stopped him and allegedly demanded 200 yuan ($28) in compensation. Onlookers captured a video showing Wang kneeling before the guard, pleading for leniency. He could not afford the fee nor the kerfuffle—it was peak lunch hour, and he needed to deliver his order on time.

The image that went viral on the afternoon of August 12.

The incident immediately went viral in WeChat groups.1 The image of the delivery driver on his knees, hands in his lap, helplessly looking up at the security guard, resonated with many delivery workers, sparking anger. Members of the delivery community decided to gather at the scene and protest the way their colleague had been treated.

As more delivery drivers arrived, tensions escalated (video). At least twenty police officers, including a specialized police unit, were called in to deescalate the situation, and the security guard was rushed away for his own safety.

That same night, local authorities issued a notification about the incident, urging people to remain calm and show more tolerance and understanding during these blazing hot summer days.

But the simmering tension beneath the surface runs deeper than just the summer heat.

In recent years, many viral videos have captured the hardships faced by Chinese food delivery workers, who endure scorching heat, heavy rain, and thunderstorms to deliver their orders. On August 21, a delivery driver in Pingyang collapsed while picking up a food order at a restaurant but insisted on completing the delivery (he was eventually taken to the hospital by ambulance). Other videos on platforms like Douyin show delivery riders breaking down during work.

The pressure they face is real, and the work they do is intense. China’s main food delivery platforms, Meituan and Ele.me, backed by tech giants Tencent and Alibaba, employ a combined 10 million delivery drivers. Their daily work is monitored by algorithmic management tools. The workload is high, the overwork is severe, the income is low, and the conditions are often unsafe.

Most of these workers are lower-educated migrant workers from rural areas who were already in vulnerable positions before taking these jobs. They face challenges such as limited job opportunities, inadequate medical care, poor nutrition, and sometimes language barriers or social alienation in China’s urban jungle.2 The digital control makes their work stressful—a late order or bad review can cost them income.

Recent studies show that these factors make China’s food delivery drivers highly susceptible to anxiety and depression. One study focusing on urban delivery drivers in Shanghai found that 46% of the drivers surveyed reported anxiety symptoms, and 18% experienced depression.3

While the recent Hangzhou incident and other viral moments have drawn attention to the stressful working conditions and weak social status of China’s food delivery workers, a new Chinese movie presents a different perspective on the gig economy.

One of the movie posters for Upstream (2024).

Upstream “逆行人生” (Nìxíng Rénshēng), a movie by director and star actor Xu Zheng (徐峥), was released on August 9. The story revolves around former programmer Gao Zhilei—played by Xu himself—who loses his job and savings. To support his family and ill father, he takes up a job as a delivery worker to survive.

The Chinese title of the movie, 逆行人生, translates to “a life against the current.” The term 逆行 (nìxíng) literally means ‘to go the wrong way’ or ‘to move in the opposite direction,’ and it has been translated as ‘upstream’ in this case. Since early 2020, Chinese state media have used the term 逆行者 nìxíngzhě, “those going against the tide” to refer to frontline workers and everyday heroes who made significant contributions or sacrifices for society, particularly during the pandemic or in emergencies such as forest fires.

Although Upstream does highlight some of the struggles faced by Chinese gig workers, it is largely a feel-good movie that avoids a deeper exploration of the marginalized status and precarious work conditions of gig workers. The title and story align with the narrative promoted by official media about China’s food delivery workers, especially during the pandemic when their work was extra demanding. Instead of lobbying for better labor conditions, they are praised as heroic and altruistic; as noble national heroes who act for the greater good. As one driver quoted in a study by Hui Huang put it: “They treat us as heroes in the media, but as slaves in reality.”4

This sentiment also plays a role in the public’s reception of Upstream, as discussed in a recent article by Sixth Tone. Many feel that the film exploits the struggles of China’s gig workers for entertainment and profit rather than genuinely advocating for their rights and well-being. Turning such harsh realities into a feel-good narrative is seen by some as “the wrong way” rather than “upstream.” Some have even described it as “rich people acting poor and making the poor pay for it.”

One Zhihu user placed the actual film poster next to an alternative version featuring delivery driver Wang in a vulnerable, knee-down position, which powerfully symbolizes how many delivery drivers perceive their weak status in society. The official poster says, “August 9 – auspicious/timely delivery,” while the alternative poster states, “August 12 – delivery not possible.”

Photo uploaded by 芒果味跃迁引擎 on Zhihu

However, there is an upside to the heightened attention on China’s food delivery workers: increased awareness. For example, the absurdity of relying on algorithms for their work is now sparking important discussions.

Delivery algorithms put pressure on riders by calculating precise delivery times based on ideal conditions, leaving little room for traffic delays, staircases, extreme weather, or restaurant preparation times. Riders can get caught in “algorithm traps” (算法陷阱) because the faster they work, the stricter the algorithm tightens delivery windows, and they may face penalties or reduced earnings if they fail to meet the expected times.

The fact that, through Upstream and the Hangzhou incident, people are now acknowledging the pressure that Meituan and Ele.me drivers face under such digital systems is already a big improvement from 2019, when debates centered on whether or not you should say “thank you” to acknowledge the service provided by delivery drivers.

“Maybe some parts of this film don’t fully connect with reality,” author Yan Lingyang (晏凌羊) wrote on Weibo about Upstream: “But under the current system, I think it’s already quite daring. It reflects various issues such as the economic downturn, housing bubbles, corporate burnout [involution], low wages for grassroots workers, lack of rights protection, and algorithm traps.”

Chinese blogger Cui Zijian (崔紫剑) recently also spoke out against the exploitation of drivers by platform companies, arguing that algorithms should be improved and suggesting that delivery riders be included in unions.

While the reception of Upstream and the Hangzhou delivery driver protest might seem to indicate that things are going the wrong way, the increased awareness actually points in the right direction—toward greater understanding of the challenging situation faced by millions of workers.

I’d love to dive deeper into topics such as these that are so relevant in everyday society and show how digital platforms impact the lives of people. Since I’m always reporting the latest trends, it often leaves little room for the more in-depth articles and overviews I’d love to write for you about the issues behind China’s hot topics & tech developments. Because of this, I’ve decided to gradually shift my focus toward deeper dives instead of shorter trend articles for What’s on Weibo. I’ll still provide timely updates on the latest trends through the Weibo Watch newsletter. I’m currently brainstorming how to make this transition, and I’ll keep you involved as I work on continuing to deliver insightful content. Finding the right balance between covering current trends and providing more contextual analyses can be challenging, but I can’t complain—thankfully, no algorithms are chasing me.

Miranda Barnes has contributed to the compilation and interpretation of the topics featured in this week’s newsletter. Ruixin Zhang has authored the insightful fan culture article, and contributed to the word of the week. As always, if you have any observations or ideas you’d like to share, please don’t hesitate to reach out to me.

Best,

Manya Koetse

(@manyapan)

1 The initial story that went viral in WeChat groups (links of screenshots) claimed that the delivery driver was a woman, and that the security guard had forced her to kneel. This detail intensified the outrage. However, it was later revealed that the driver was actually a thin, male worker who knelt voluntarily, in hopes of speeding up the process.

2 See Peng, Yuxun, et al., “Status and Determinants of Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression among Food Delivery Drivers in Shanghai, China,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20 (2022): 1; and Hui Huang, “Riders on the Storm: Amplified Platform Precarity and the Impact of COVID-19 on Online Food-delivery Drivers in China,” Journal of Contemporary China 31, no. 135 (2022): 351, 363.

3 See Peng, Yuxun, et al., “Status and Determinants of Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression among Food Delivery Drivers in Shanghai, China,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20 (2022): 10.

4 See Huang Hui, “Riders on the Storm: Amplified Platform Precarity and the Impact of COVID-19 on Online Food-delivery Drivers in China,” Journal of Contemporary China 31, no. 135 (2022): 363.

What’s New

Ping Pong Fandom | The table tennis final between Chen Meng and Sun Yingsha in Paris exposed troubling fan dynamics, sparking discussions on the clash between fandom culture & the Olympic spirit. Read our latest on the influence of fandom culture in Chinese table tennis 🏓 🔗

The Big Olympic File | Before the Paralympics will start on August 28, time to reflect on what happened during the Olympics. We reported and wrapped it up! Capturing all the must-know medals and online discussions happening on the sidelines of the Olympics, here’s the What’s on Weibo China at Paris 2024 Olympic File.

Medals and Memes | The 2024 Paris Olympics captivated Chinese social media, not just for the gold medal victories but also for the many moments that unfolded on the sidelines. Here are the 10 most popular ones.

The Human Bone Controversy | Chinese online media was flooded with 404 errors earlier this month as many of the articles published about the human bone scandal—where the Chinese company Shanxi Aorui illegally acquired thousands of corpses to produce bone graft materials sold to hospitals—were taken offline. From 2015-2023, Shanxi Aorui forged body donation registration forms and other documents to purchase corpses from hospitals, funeral homes and crematoriums to produce bone implant materials sold to hospitals.

What’s Trending

🐒 Black Myth Wukong

A Chinese game that has been in development for over four years is top trending on Weibo this week. More than that: it’s a national sensation. Black Myth: Wukong (黑神话悟空) was officially released on August 20, surpassing all expectations. Within an hour of its release, it topped the “Most Played” list on Steam, with over 2 million concurrent players.

Developed by Game Science, a startup founded by former Tencent employees, Black Myth: Wukong draws inspiration from the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West. This epic tale, filled with heroes and demons, follows the supernatural monkey Sun Wukong as he accompanies the Tang dynasty monk Xuanzang on a pilgrimage to India to obtain Buddhist sūtras (holy scriptures). The game focuses on Sun Wukong’s story after this journey. Black Myth: Wukong has been such a massive success that anything associated with it is also going viral—a merchandise collaboration with Luckin Coffee sold out instantly.

🥇 Olympic Heroes Hailed at Home

China’s Olympic champions, including Quan Hongchan (全红婵), who we also discussed in our last newsletter, have received warm welcomes home as their hometowns were transformed into temporary pilgrimage sites, complete with medal ceremonies and huge posters. There have been many touching moments during the champions’ return. For example, Boxing Gold medalist Wu Yu jumped into her mom’s arms and cried like a little kid after returning from her Paris adventure.

In addition to the warm receptions in their hometowns, the champions were also honored in Beijing at the Great Hall of the People, where Xi Jinping met with the athletes on August 20 and praised them for their performance and sportsmanship throughout the Paris Games. A related hashtag has garnered 360 million views on Weibo ( #中国体育代表团总结大会举行#)

🚨 Magic Carpet Ride Gone Wrong

The “magic carpet ride” at the popular Detian Waterfall scenic area in Guangxi’s Chongzuo drew significant attention on social media earlier this month after a malfunction led to tragic consequences. This attraction, designed to transport visitors up the mountain as they sit backward on a moving belt, suddenly malfunctioned on August 10, causing passengers to slide uncontrollably downwards (here you can see how the attraction normally operates).

The accident resulted in one tourist’s death and injuries to 60 others. A joint investigation team was established to determine the cause of the incident. Preliminary findings suggest that a steel buckle at the belt’s joint broke, causing the belt to rapidly slide downward. With passengers spaced about a meter apart on the conveyor belt, the sudden movement led to collisions, with some individuals being crushed, particularly at the lower end. Those responsible for the attraction’s operation and maintenance have been detained in accordance with the law for their roles in the incident, which will be further investigated.

🍵 Eileen Gu Controversy

Whether it’s her athletic career or personal life, Eileen Gu (谷爱凌) always seems to find herself trending in China. The American-born freestyle skier and gold medalist who represented China at the 2022 Beijing Olympics sparked discussions during the Paris Olympics due to her connection with Léon Marchand, the renowned French Olympic swimmer. Marchand faced significant backlash on Chinese social media after being accused of ignoring a handshake from Team China’s coach Zhu Zhigen (朱志根). A brief video of the incident went viral, showing the Chinese coach approaching Marchand to congratulate him, only for Marchand to seemingly ignore him and walk away.

Amid the controversy, netizens noticed that Gu, who had previously interacted with Marchand online, deleted her comments on his Instagram, including a compliment on his latest Olympic victory (“incredible”) (#谷爱凌删了给马尔尚的所有ins评论#). However, when videos surfaced of Gu dancing closely with Marchand, she was accused of being two-faced or insincere. While some initially saw her deletion of the interactions as a patriotic gesture, many now believe she was simply being opportunistic.

But Gu is clapping back at her haters, suggesting that she can never please everyone. When someone called her out for being “a traitor” to her country, Gu reportedly replied, “Which one?” The issue of Gu’s nationality has been a somewhat sensitive topic since she first represented China, with many questioning whether she holds a Chinese or American passport (as China does not recognize dual nationality). Gu’s previous statement, “I’m American when in the US and Chinese when in China,” has also triggered dissatisfaction among Chinese audiences. On Instagram, she has now confronted her haters: “In the past five years, I’ve won 39 medals representing China and spoken out for China and women on the world stage. What have the haters done for the country?”

💍 New Marriage Rules

A revised draft regulation on marriage registration introduced by China’s Ministry of Civil Affairs last week has sparked significant online discussion. One notable change is that couples will no longer need their hukou, or household register, to get married. Traditionally, this document is often held by parents, meaning that those who wish to marry had to obtain it—essentially seeking parental approval. By removing this requirement, the process is simplified, giving individuals more freedom to marry, even if their parents disagree.

However, the draft regulation is drawing criticism, primarily due to the inclusion of a 30-day cooling-off period for divorce. This cooling-off period (“冷静期”) allows either party to withdraw their divorce application within 30 days of filing. Although introduced in a draft as early as 2018, it continues to generate debate. Many feel that while the revision appears to grant more freedom in marriage, it restricts the freedom to divorce in a timely manner. Some say this is like a “loose entry, strict exit” (宽进严出) policy, similar to Chinese university admissions. One popular comment called it “fake freedom.” The draft regulation is open for public feedback until September 11.

🚴 Discussions over Cycling Boy’s Death

A tragic incident in Hebei has sparked significant online discussions. In Rongcheng County, an eleven-year-old boy who was cycling with his father in a group of cyclists fell down and was run over by a car coming from the opposite direction. A dashcam video captured the group riding in the middle of the road, leaving the oncoming vehicle with little room or time to avoid the collision. The boy succumbed to his injuries shortly after the accident.

The incident has led to broader debates about the father’s responsibility. According to road safety laws, the eleven-year-old should not have been cycling on a public road, especially not in the middle of it. The situation is further complicated by reports that people had previously warned the father about the dangers of bringing his young son on high-speed cycling trips, warnings which he allegedly ignored. Although the father initially attempted to shift the blame onto the driver for speeding, public opinion has largely condemned him for being irresponsible, with devastating consequences.

🇨🇳 Chinese Flag Controversy

A hotel in Paris, part of a Taiwanese chain, became the center of online attention this August after it failed to include the Chinese flag in its Olympic-themed decorations. The issue was brought to light by a Chinese influencer who posted a video accusing the Evergreen Laurel Hotel (长荣桂冠酒店) of refusing to display the Chinese flag, even after the influencer offered to provide one. The incident sparked significant backlash, leading domestic travel platforms like Ctrip and Meituan to delist the hotel’s booking options, including those at its Shanghai location. The hotel eventually issued an apology, but many netizens found it too vague, as it did not directly address the flag incident, instead focusing on general dissatisfaction with their decorations. The Chinese Embassy in France has since commented on the issue, expressing support for Chinese people, both at home and abroad, in their efforts to “remain united and uphold patriotic values.”

What’s Noteworthy

The WeChat account Zhenguan (贞观) reported on August 16 about a tragic incident involving a 33-year-old woman from a small, impoverished village in Ningxia who died alone in her rented 30th-floor apartment in Xi’an. Her body was not discovered for a long time, and by the time it was found, it had decomposed to the point of being unrecognizable. In the article, titled “A Women From Out of Town Died in the Apartment I Rented Out” (“一个外地女孩,死在了我出租的公寓”), which has since been deleted, a landlord shares their story of how they discovered the single young woman had died inside the studio apartment. The article paints a picture of a once-bright rural girl who became disillusioned as the competitive educational system and the pressures of city life crushed her spirit. The woman, who depended on her family’s financial support, hadn’t ordered or cooked any food for nearly twenty days since she was last seen in May, suggesting she most likely starved to death in her apartment.

The article quickly went viral over the weekend. The incident, which allegedly took place during the summer, resonated with people as they began filling in the gaps of the story with their own interpretations. They felt for the woman, who had worked hard in life but had found herself unable to live up to expectations. Some saw the young woman’s story as a tragic reflection of the struggles in contemporary Chinese society. Some blamed city life, others blamed rural culture. But many also doubted the story’s authenticity.

After Chinese media outlets like Zhengzai Xinwen (正在新闻) began investigating the matter, it was revealed that some details in the story were inaccurate. The incident did not occur in Xi’an but in Xianyang. People from the woman’s hometown mentioned that she was socially withdrawn and may have struggled with mental health issues, though she was never formally diagnosed. Local police did confirm that the incident is real and that it is still under investigation by a local branch of the Xianyang Public Security Bureau. Regardless of the exact circumstances, the woman’s story has struck a chord, with one popular comment on Weibo stating: “There are countless others like her in society who are experiencing the same struggles. No matter what you’re going through, I hope you don’t give up on life.”

What’s Popular

This summer’s Olympic fever in China has been evident across various e-commerce platforms. Whether it was the sudden popularity of Zheng Qinwen’s tennis skirt or the craze over diver Quan Hongchan’s ugly animal slippers, Chinese consumers have eagerly embraced Olympic-themed shopping.

Recognizing the influence of athletes during and after the Olympics, brands have tapped into their potential by launching various collaborations. A particularly successful example is the plush paddles endorsed by Olympic table tennis star Fan Zhendong (樊振东). The 27-year-old national table tennis player, often referred to as the “National Ping Pong God” (国乒男神), not only clinched double gold in Paris but also endorses several brands, including the British Jellycat brand, which created the plush paddle toys.

One popular video shows Fan playing table tennis with the plush paddle toy, which quickly sold out after his Olympic victory. The toy was restocked twice in three days before selling out again. Many commenters praised the toy for being so cute, and in light of Wang Chuqin’s now-famous broken paddle incident, others joked that it’s a good thing the plush paddles are unbreakable.

What’s Memorable

China’s well-known political and social commentator Hu Xijin (胡锡进) has been noticeably absent from Chinese social media for about a month. The former editor-in-chief of the Global Times has not posted on his account since July 27—an extraordinary, unannounced, and unexplained pause from his typically daily social media activity. In light of Hu’s sudden silence, we take a look back eight years into the What’s on Weibo archive, when another social media commentator and real estate tycoon, Ren Zhiqiang (任志强), abruptly went silent, and his account subsequently disappeared.

Weibo Word of the Week

Fan Cultured | Our Weibo word of the week is ‘fan-cultured’ or ‘fandom-ization’ (fànquānhuà 饭圈化). While fànquān 饭圈 literally means “fan circle,” the suffix huà 化 is generally used to indicate a process of transformation or turning into something, similar to the “-ization” suffix in English.

The term fànquānhuà 饭圈化 refers to the recently much-discussed phenomenon where something—often outside the realms of entertainment—receives passionate support from people who begin to form online fan circles around it, changing the dynamics in ways that resemble the relationships between celebrity idols and their fans.

A recent example of something being “fan-cultured” or “fandom-ized” is how fans have started to form extremely strong communities around China’s table tennis stars, defending them as if they were idols. This fan behavior has been criticized by Chinese authorities, who see it as toxic fan culture that goes against the Olympic spirit (read more).

But “fandom-ization” goes beyond sports. There are also strong fan club dynamics surrounding Chinese pandas. Even inanimate objects can become “fan-cultured.” For example, the Little Forklift Truck (小叉车) that was part of the construction of the Huoshenshan emergency specialty field hospital during the early days of the Covid crisis. The construction process was live-streamed, and millions of viewers found the little truck—working tirelessly around the clock—so cute and brave that it became “fan-cultured.”

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

China Arts & Entertainment

The Rising Influence of Fandom Culture in Chinese Table Tennis

The match between Sun Yingsha and Chen Meng in Paris highlighted how the fan culture surrounding Chinese table tennis can clash with the Olympic spirit.

Published

4 weeks agoon

August 16, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

During the Paris Olympics, not a day went by without table tennis making its way onto Weibo’s trending lists. The Chinese table tennis team achieved great success, winning five gold medals and one silver.

However, the women’s singles final on August 3rd, between Chinese champions Chen Meng (陈梦) and Sun Yingsha (孙颖莎), took viewers by surprise due to the unsettling atmosphere. The crowd overwhelmingly supported Sun Yingsha, with little applause for Chen Meng, and some hurled insults at her. Even the coaching staff had stern expressions after Chen’s win.

This bizarre scene sparked heated discussions on Chinese social media, exposing the broader audience to the chaotic and sometimes absurd dynamics within China’s table tennis fandom.

“I welcome fans but reject fandom culture.”

When Sun Yingsha and Chen Meng faced off in the women’s singles final, the medal was destined for ‘Team China’ regardless of the outcome; the match should have been a celebration of Chinese table tennis.

However, the match held significant importance for both Sun and Chen individually. Chen Meng, the defending champion from the previous Olympics, was on the verge of making history by retaining her title. Meanwhile, Sun Yingsha, an emerging star who had already claimed singles titles at the World Cup and World Championships, was aiming to complete a career Grand Slam (World Championships, World Cup, and Olympics).

[center] Announcement of the Chen (L) vs Sun (R) match by People’s Daily on social media.[/center]

Sun Yingsha has clearly become a public favorite. On Weibo, the table tennis star ranked among the most beloved athletes in popularity lists.

This favoritism among Chinese table tennis fans was evident at the venue. According to reports from a Chinese audience member, anyone shouting “Go Chen Meng!” (“陈梦加油”) was quickly silenced or booed, while even cheering “Come on China!” (“中国队加油”) was met with ridicule. After Chen Meng’s 4-2 victory, many in the audience expressed their frustration and chanted “refund” during the award ceremony. Meanwhile, social media was flooded with hateful posts cursing Chen for winning the match.

For many who were unfamiliar with the off-court drama, the influence of fandom culture on the Olympics was shocking. However, in the world of Chinese table tennis, such extreme fan behavior has been brewing for some time. Even during the eras of Ma Long (马龙) and Zhang Jike (张继科), there were already fans who would turn against each other and others.

This year’s men’s singles champion, Fan Zhendong (樊振东), had long noticed the growing influence of fandom culture. In recent years, he has repeatedly voiced his discomfort with fan activities like “airport send-offs” and “fan meet-and-greets.” Earlier this year, he took to social media to reveal that he and his loved ones were being harassed by both overzealous fans and haters, and that he was considering legal action. He made it clear: “I welcome fans but reject fandom culture.” His consistent stance against fandom has helped cultivate a relatively rational fan base.

“What has happened to Chinese table tennis fans over the years?”

On Weibo, a blogger (@3号厅检票员工) posed a question that struck a chord with many, garnering over 30,000 likes: “What has happened to Chinese table tennis fans over the years?”

In the comments, many blamed Liu Guoliang (刘国梁) for fueling the fan culture around table tennis. Liu, the first Chinese male player to achieve the Grand Slam, retired in 2002 and then became a coach for the Chinese table tennis team. His coaching career has been highly successful, leading players like Ma Long and Xu Xin (许昕) to numerous championships.

Beyond coaching, Liu has been dedicated to commercializing table tennis. Compared to international tournaments in sports like tennis or golf, the prize money for Chinese table tennis players is only about one-tenth of those sports. Fan Zhendong has publicly stated on Weibo that the prize money for their competitions is too low compared to badminton. Liu believes table tennis has significant untapped commercial potential that has yet to be fully realized.

Under Liu’s leadership, the commercialization of the Chinese table tennis team began after the Rio Olympics, where China won all four gold medals. Viral internet memes like “Zhang Jike, wake up!” (继科你醒醒啊) and “The chubby guy who doesn’t understand the game” (不懂球的胖子) made both the sport and its athletes wildly popular in China.

Seeing the opportunity, Liu quickly increased the team’s exposure, encouraging players to create Weibo accounts, do live streams, star in films, and participate in variety shows. This approach rapidly turned the Chinese table tennis team into a “super influencer” in the Chinese sports world.

While this move has certainly increased the athletes’ visibility, it has also drawn criticism: is this kind of commercialization and celebrity status the right path for China’s table tennis? Successful commercialization requires a mature system for talent selection, team building, and athlete management. However, the selection process in Chinese table tennis remains opaque, the current team-building system shows little promise, and young athletes struggle to break through.

Additionally, athlete management appears amateurish. After watching an interview with Chinese tennis player Zheng Qinwen (郑钦文), a Douban netizen commented that Liu Guoliang’s plan for commercializing athletes is highly unprofessional—relying mainly on their personal charisma to attract attention. The most common criticism is that Liu and the Table Tennis Association should let professionals handle the professional work. Without a solid foundation for commercialization, the current focus on hype and marketing in Chinese table tennis may temporarily boost ticket sales but could ultimately backfire.

“Didn’t you say you want to crack down on fan culture?”

In response to the controversy surrounding the Chen vs. Sun match, the Beijing Daily published an article titled “How Can We Allow Fandom Violence to Disturb the World of Table Tennis?” The article addressed the growing problem of “fandom culture” infiltrating table tennis, a trend that originated in the entertainment world. It highlighted how extreme fan behavior, including online abuse and disruptive actions during matches, harms both the sport and the mental well-being of athletes. While fan enthusiasm is important, the article stressed that it must remain within rational limits.

This article foreshadowed actions taken shortly after. On August 7th, China’s Ministry of Public Security announced an online crackdown on chaotic sports-related fan circles. Social media platforms responded swiftly: Weibo deleted over 12,000 posts and banned more than 300 accounts, while Xiaohongshu, Bilibili, and Migu Video removed over 840,000 posts and banned or muted more than 5,300 accounts.

The campaign against fan culture sparked online debate. Some netizens criticized the official stance on “fandom” as overly simplistic. The Chinese term for “fandom,” 饭圈 (fànquān), contains a homophone for “fan,” referring to enthusiastic supporters of celebrities. In contemporary Chinese discourse, the term is often linked to the idol industry and carries negative, gender-biased connotations, particularly towards “irrational female fans chasing male idols.”

One Weibo post argued that commercialized sports, like football, are inherently tied to fan loyalty, belonging, and exclusivity. Disruptions among fans are not solely due to “fandom” but are often influenced by larger forces, such as capital or authorities. In the table tennis final, even the coaching team’s dissatisfaction with Chen Meng’s victory points to underlying problems beyond fan behavior.

While public backlash against “fandom” in sports often stems from concerns over its toxicity and violence, as blogger Yuyu noted, internal conflicts and power struggles have always existed in competitive sports. Framing these issues solely as “fandom problems” risks oversimplifying the situation and overlooks challenges such as commercialization failures, poor youth development, and internal factionalism within sports teams. The simplistic blame on “fandom culture” is seen by some as a distraction from these real issues, further fueling public frustration.

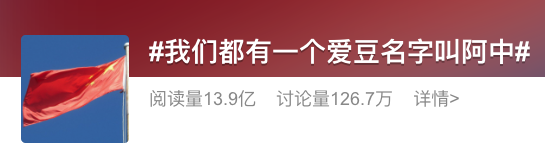

This public frustration is evident in a 2019 Weibo post and hashtag from People’s Daily. The five-year-old post personified China as a young male idol, promoting patriotism through fandom culture with the slogan “We all have an idol named ‘A Zhong’ (#我们都有一个爱豆名字叫阿中#)” [‘A Zhong’ was used as a nickname to refer to a personified China]. This promotion of ‘China’ as an idol with a 1.4 billion ‘fandom’ resurfaced during the Hong Kong protests.

Hashtag: “We all have an idol named Azhong” [nickname for China]

Now, after state media harshly criticized fandom culture, netizens have revisited the post, bringing it back into the spotlight. Recent comments on the post are filled with sarcasm, highlighting how fandom is apparently embraced when convenient and scapegoated when problems arise.

Post by People’s Daily promoting China as an “idol.”

“Didn’t you say you wanted to crack down on fan culture?” one commenter wondered.

Chen Meng, the Olympic table tennis champion, has also addressed the fan culture surrounding the 2024 Paris matches. She expressed her hope that, in the future, fans will focus more on the athletes’ “fighting spirit” on the field. True sports fans, she suggested, should be able to celebrate when their favorite athlete wins and accept it when they lose. “Because that’s precisely what competitive sports are all about,” she said.

By Ruixin Zhang

edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Land Rover Woman Controversy Explained

China at the 2024 Paralympics: Golds, Champions, and Trending Moments

“Land Rover Woman” Sparks Outrage: Qingdao Road Rage Incident Goes Viral in China

Fired After Pregnancy Announcement: Court Case Involving Pregnant Employee Sparks Online Debate

Weibo Watch: Going the Wrong Way

China’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

Hero or Zero? China’s Controversial Math Genius Jiang Ping

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Why Chinese Publishers Are Boycotting the 618 Shopping Festival

About Wang Chuqin’s Broken Paddle at Paris 2024

Chinese Sun Protection Fashion: Move over Facekini, Here’s the Peek-a-Boo Polo

The Beishan Park Stabbings: How the Story Unfolded and Was Censored on Weibo

China at Paris 2024 Olympics Trend File: Medals and Moments on Chinese Social Media

Stolen Bodies, Censored Headlines: Shanxi Aorui’s Human Bone Scandal

The “City bu City” (City不City) Meme Takes Chinese Internet by Storm

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight4 months ago

China Insight4 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music6 months ago

China Music6 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital12 months ago

China Digital12 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Insight6 months ago

China Insight6 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

Ben

November 16, 2018 at 10:33 am

In the picture for “#18 Heaven’s Above (苍天在上)”, the character seems to be holding a smartphone – possibly an iPhone given what looks to be an apple on the back side. That would be anachronistic for a 1995 series I think?

Admin

November 16, 2018 at 10:41 am

Well spotted, Ben! You’re right! That was an image from a modern remake mini-series of Heaven’s Above (苍天在上), not the 1995 version. We’ve now replaced with an image from the original show. Thanks for the heads up 🙂

autraka

November 22, 2018 at 6:59 am

Wish you included 武林外传、还珠格格 and more TV dramas based on 金庸‘s novels.

Brown

January 2, 2019 at 10:58 am

Chinese TVs set in Qing Dynasty are an amazing series for me. I love the Story of Yanxi Palace especially. I have found the top 10 related Qing Dynasty TVs from here

https://chinausual.com/top-10-chinese-tv-series-set-in-qing-dynasty/

Jason

February 23, 2019 at 9:57 am

Actually “White Deer Plain” 白鹿原 is in Shaanxi(陕西). Not Shanxi(山西)。