China Insight

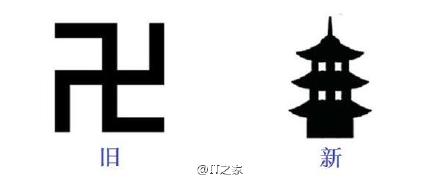

Pay Attention, Confused Foreigners: ‘Wan’ (卍) is Not a Nazi Symbol

Japan wants to get rid of the Buddhist manji-symbol (卍) on city maps, as foreigners associate it with the Nazi swastika. In China, where the symbol is known as the ‘wan’ character, some netizens seem to find the controversy entertaining.

Published

9 years agoon

Japan’s official map-making organization wants to get rid of the Buddhist manji symbol (卍) that marks the location of temples on city maps, as foreigners associate it with the Nazi swastika. In China, where the symbol is known as the ‘wan’ character, some netizens seem to find the controversy entertaining.

This week several international media, including

the BBC, wrote about the decision of the Japanese map-making association to change its manji symbol on tourist maps.

The 卍-symbol indicates the location of temples, but is often seen as the Nazi swastika by foreigners. With the Rugby World Cup and Olympics taking place in Japan in 2019 and 2020, Japanese authorities deem it is better to remove the symbol in order to avoid any misunderstanding amongst international visitors.

“Ignorant foreign travelers simply don’t understand Buddhist traditions”.

The news was also reported by Chinese media. The manji symbol is used in China as well, where it is a character pronounced as ‘wàn’.

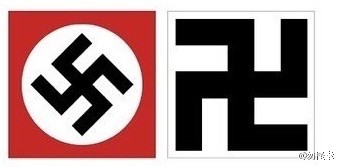

China’s Sohu news writes that the Japanese manji is actually not the same as the Nazi swastika: the first has arms going anticlockwise (卍) whereas the arms of the Nazi symbol go clockwise (卐).

The article says that Hitler’s Nationalist Socialist Party designed the swastika that way because the German words for state and society both start with an S. This is allegedly why they designed the swastika in an S-shape.

Another difference, according to Sohu, is that the Buddhist swastika usually is gold, whereas the Nazi symbol is black.

The confusion between the two symbols is mostly created by foreigners, Sohu writes, who do not know the difference. Japanese netizens reportedly complain about “ignorant foreign travelers”, who simply “do not understand Buddhist traditions”. They should not protest its use – “When in Rome,” they say: “do as the Romans do.”

“By all means, don’t let them come to Chinese Buddhist temples. They’ll go crazy”.

On Chinese social media network Sina Weibo, a netizen called Wuguaixing seems entertained by the news. The micro-blogger, a PhD student at Tokyo University with over 100,000 Weibo followers, writes on his account:

“Ha ha! The much used Buddhist ‘wan’ (卍) character that marks temples on Japanese maps is opposed by foreigners, who think it is the Nazi ‘卐’ symbol. They now want to get rid of it.”

Other Weibo users commented on the post, saying: “Foreign tourists are just not culturally educated at all!” And: “By all means, don’t let them come to Chinese Buddhist temples. They’ll go crazy!”

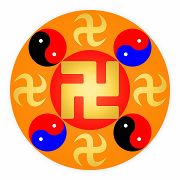

The symbol can be found in many of China’s temples, either depicted on the Buddha or in ornaments.

The writer of one of the post’s most popular comments wonders why the manji symbol is a problem at all: “Does this centuries-old symbol really need to make way for the Nazi symbol, that is just some decades old?”

One Weibo user remarks: “If this was about any other Asian country, it would be no problem. But because of Japan’s past war crimes, the issue is very sensitive.”

“Where did everyone’s IQ go?!”

Some Weibo users address the history of the symbol: “Strictly speaking, this is an old Hindu symbol that was then used by Buddhism.” This comment is backed up by a netizen nicknamed Black & White, who writes: “The 卍 and the 卐 are two different characters, and they both read as ‘wàn’.”

According to Brittanica Academic, both symbols, either clockwise or anti-clockwise, are referred to as a swastika. It comes from the Sanskrit svastika meaning “conductive to well-being”, and is an ancient symbol of prosperity and good fortune. It represents the revolving sun, fire, or life, Buddhas Online explains.

According to the Encyclopedia Brittanica:

In the Buddhist tradition the swastika symbolizes the feet, or the footprints, of the Buddha. It is often placed at the beginning and end of inscriptions, and modern Tibetan Buddhists use it as a clothing decoration. With the spread of Buddhism, the swastika passed into the iconography of China and Japan, where it has been used to denote plurality, abundance, prosperity, and long life.

The swastika was used as a sign of ‘Aryan race’ in the 19th century, and was adopted by Nazism in the 20th century (Quinn 1994, x).

“Where did everyone’s IQ go?!” one Weibo user wonders.

China’s Ifeng news wrote an article about the swastika and the issue of the clockwise and anticlockwise arms. It explains that Buddhism actually uses the sign in both ways, and they both represent wisdom and compassion.

Although the issue seems more nuanced than a simple (anti)clockwise explanation, for some netizens, it’s not complicated at all: “The 卍 is a Buddhist symbol, and the 卐 is a Nazi symbol, please don’t mix them up.”

– By Manya Koetse

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

References

Quinn, Malcolm. 1994. The Swastika: Constructing the Symbol. London/New York: Routledge.

Featured image from Flickr: https://c2.staticflickr.com/6/5179/5435812352_e2578ba5b8.jpg

©2016 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Digital

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

As American ‘TikTok Refugees’ flock to China’s Xiaohongshu (Rednote), their encounter with ‘Li Hua’ strikes a chord in divided times.

Published

1 month agoon

January 20, 2025

FROM THE WEIBO WATCH PREMIUM NEWSLETTER

China’s Xiaohongshu (Rednote) has seen an unprecedented influx of foreign “TikTok refugees” over the past week, giving rise to endless jokes. But behind this unexpected online migration lie some deeper themes—geopolitical tensions, a desire for cultural exchange, and the unexpected role of the fictional character Li Hua in bridging the divide.

Imagine you are Li Hua (李华), a Chinese senior high school student. You have a foreign friend, far away, in America. His name is John, and he has asked you for some insight into Chinese Spring Festival, for an upcoming essay has to write for the school newspaper. You need to write a reply to John, in which you explain more about the history of China’s New Year festival and the traditions surrounding its celebrations.

This is the kind of writing assignment many Chinese students have once encountered during their English writing exams in school during the Gaokao (高考), China’s National College Entrance Exams. The figure of ‘Li Hua’ has popped up on and off during these exams since at least 1995, when Li invited foreign friend ‘Peter’ to a picnic at Renmin Park.

Over the years, Li Hua has become somewhat of a cultural icon. A few months ago, Shangguan News (上观新闻) humorously speculated about his age, estimating that, since one exam mentioned his birth year as 1977, he should now be 47 years old—still a high school student, still helping foreign friends, and still introducing them to life in China.

Li Hua: the connector, the helper, the icon.

This week, however, Li Hua unexpectedly became a trending topic on social media—in a week that was already full of surprises.

With a TikTok ban looming in the US (delayed after briefly taking effect on Sunday), millions of American TikTok users began migrating to other platforms this month. The most notable one was the Chinese social media app Xiaohongshu (now also known as Rednote), which saw a massive influx of so-called “TikTok refugees” (Tiktok难民). The surge propelled Xiaohongshu to the #1 spot in app stores across the US and beyond.

This influx of some three million foreigners marked an unprecedented moment for a domestic Chinese app, and Xiaohongshu’s sudden international popularity has brought both challenges and beautiful moments. Beyond the geopolitical tension between the US and China, Chinese and American internet users spontaneously found common ground, creating unique connections and finding new friends.

While the TikTok/Xiaohongshu “honeymoon” may seem like just a humorous trend, it also reflects deeper, more complex themes.

✳️ National Security Threat or Anti-Chinese Witchhunt?

At its core, the “TikTok refugee” trend has sprung from geopolitical tensions, rivalry, and mutual distrust between the US and China.

TikTok is a wildly popular AI-powered short video app by Chinese company ByteDance, which also runs Douyin, the Chinese counterpart of the international TikTok app. TikTok has over 170 million users in the US alone.

A potential TikTok ban was first proposed in 2020, amid escalating US-China tensions. President Trump initiated the move, citing security and data concerns. In 2024, the debate resurfaced in global headlines when President Biden signed the “Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act,” giving ByteDance nine months to divest TikTok or face a US ban.

TikTok, however, has continuously insisted it is apolitical, does not accept political promotion, and has no political agenda. Its Singaporean CEO Shou Zi Chew maintains that ByteDance is a private business and “not an agent of China or any other country.”

🇺🇸 From Washington’s perspective, TikTok is viewed as a national and personal security threat. Officials fear the app could be used to spread propaganda or misinformation on behalf of the Chinese Communist Party.

🇨🇳 Beijing, meanwhile, criticizes the ban as an act of “bullying,” accusing the US of protectionism and attempting to undermine China’s most successful internet companies. They argue that the ban reflects America’s inability to compete with the success of Chinese digital products, labeling the scrutiny around TikTok as a “witch hunt.”

Political cartoon about the American “witchhunt” against TikTok, shared on Weibo in 2023, also published on Twitter by Lianhe Zaobao.

“This will eventually backfire on the US itself,” China’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin predicted in 2024.

Wang turned out to be quite right, in a way.

When it became clear in mid-January that the ban was likely to become a reality, American TikTok users grew increasingly frustrated and angry with their government. For many of these TikTok creators, the platform is not just a form of entertainment—it has become an essential part of their income. Some directly monetize their content through TikTok, while others use it to promote services or products, targeting audiences that other platforms like Facebook, Instagram, or X can no longer reach as effectively.

Initially, the mass migration of American users to Xiaohongshu was a symbolic protest against US policies. Users advocated for the right to choose their preferred social media, and voiced their frustration at how their favorite app had become a pawn in US-China geopolitical tensions. Rejecting the narrative that “data must be protected from the Chinese,” many pointed out that privacy concerns were equally valid for US-based platforms. As an act of playful political defiance, these users downloaded Xiaohongshu to demonstrate they didn’t fear the government’s warnings about Chinese data collection.

(If they had the option, by the way, they would have installed Douyin—the actual Chinese version of TikTok—but it is only available in Chinese app stores, whereas Xiaohongshu is accessible in international stores, so it was picked as ‘China’s version of TikTok.’)

Xiaohongshu is actually not the same as TikTok at all. Founded in 2013, Xiaohongshu (literal translation: Little Red Book) is a popular app with over 300 million users that combines lifestyle, travel, fashion, and cosmetics with e-commerce, user-generated content, and product reviews. Like TikTok, it offers personalized content recommendations and scrolling videos, but is otherwise different in types of engagement and being more text-based.

As a Chinese app primarily designed for a domestic audience, the sudden wave of foreign users caused significant disruption. Xiaohongshu must adhere to the guidelines of China’s Cyberspace Administration, which requires tight control over information flows. The unexpected influx of foreign users undoubtedly created challenges for the company, not only prompting them to implement translation tools but also recruiting English-speaking content moderators to manage the new streams of content. Foreigners addressing sensitive political issues soon found their accounts banned.

Of course, there is undeniable irony in Americans protesting government control by flocking to a Chinese app functioning within an internet system that is highly controlled by the government—a move that sparked quite some debate and criticism as well.

✳️ The Sino-American ‘Dear Li Hua’ Moment

While the initial hype around Xiaohongshu among TikTok users was political, the trend quickly shifted into a moment of cultural exchange. As American creators introduced themselves on the platform, Chinese users gave them a warm welcome, eager to practice their English and teach these foreign newcomers how to navigate the app.

Soon, discussions about language, culture, and societal differences between China and the US began to flourish. Before long, “TikTok refugees” and “Xiaohongshu natives” were collaborating on homework assignments, swapping recipes, and bonding through humor.

For instance, Chinese users jokingly asked the “TikTok refugees” to pay a “cat tax” for seeking refuge on their platform, which American users happily fulfilled by posting adorable cat photos. American users, in turn, joked about becoming best friends with their “Chinese spies,” playfully mocking their own government’s fears about Chinese data collection.

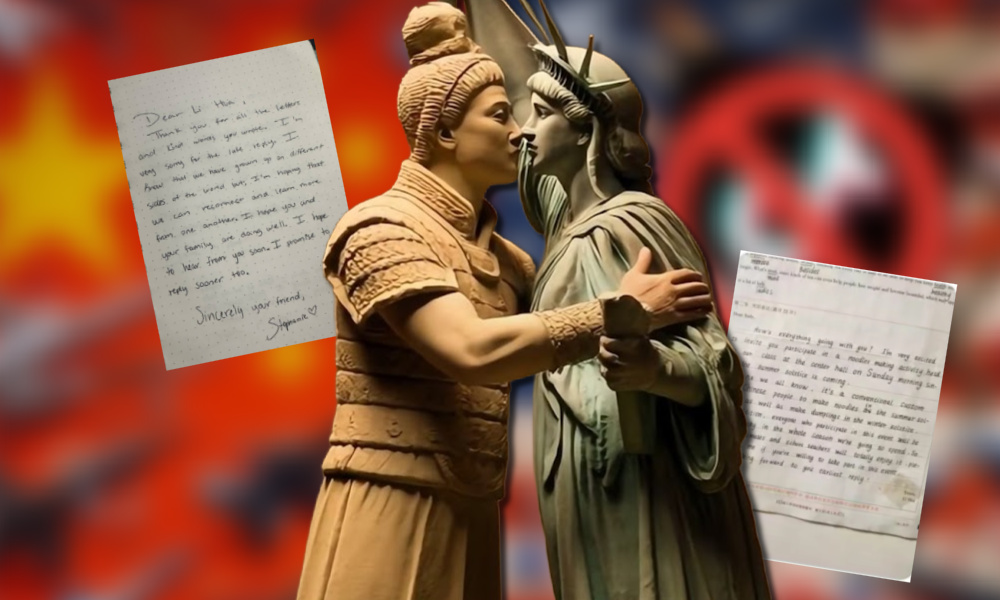

The newfound camaraderie sparked creativity, as users began generating humorous images celebrating the bond between American and Chinese netizens—like Ronald McDonald cooking with the Monkey King or the Terra Cotta Soldier embracing the Statue of Liberty. Later, some images even depicted the pair welcoming their first “baby.”

🇺🇸 At the same time, it became clear just how little Americans and Chinese truly know about each other. Many American users expressed surprise at the China they discovered through Xiaohongshu, which contrasted sharply with negative portrayals they’ve seen in the media. While some popular US narratives often paint Chinese citizens as “brainwashed” by their government, many TikTok users began to reflect on how their own perspectives had been shaped—or even “manipulated”—by their media and government.

🇨🇳 For Chinese users, the sudden interaction underscored their digital isolation. Over the past 15 years, China has developed its own tightly regulated digital ecosystem, with Western platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube inaccessible in the mainland. While this system offers political and economic advantages, it has left many young Chinese people culturally hungry for direct interaction with foreigners—especially after years of reduced exchange caused by the pandemic, trade tensions, and bilateral estrangement. (Today, only some 1,100 American students are reportedly studying in China.)

The enthusiasm and eagerness displayed by American and Chinese Xiaohongshu users this week actually underscores the vacuum in cultural exchange between the two nations.

As a result of the Xiaohongshu migration, language-learning platform Duolingo reported a 216% rise in new US users learning Mandarin—a clear sign of growing interest in bridging the US-China divide.

Mourning the lack of intercultural communication and celebrating this unexpected moment of connection, Xiaohongshu users began jokingly asking Americans if they had ever received their “Li Hua letters.”

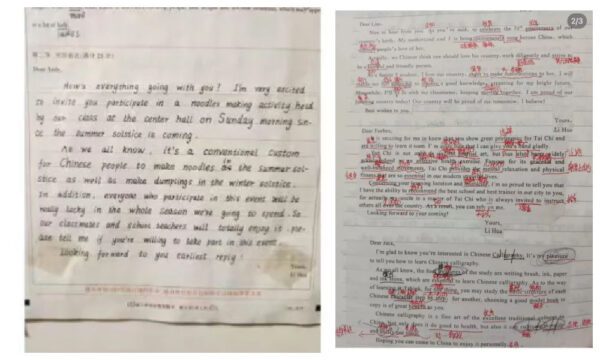

What started as some lighthearted remarks evolved into something much bigger as Chinese users dug up their old Gaokao exam papers and shared the letters they had written to their imaginary foreign friends years ago. These letters, often carefully stored in drawers or organizers, were posted with captions like, “Why didn’t you reply?” suggesting that Chinese students had been trying to reach out for years.

Example letters on Xiaohongshu: ‘Li Hua’ writing to foreign friends.

The story of ‘Li Hua’ and the replies he never received struck a chord with American Tiktok users. One user, Debrah.71, commented:

“It was the opposite for us in the USA. When I was in grade school, we did the same thing—we had foreign pen pals. But they did respond to our letters.”

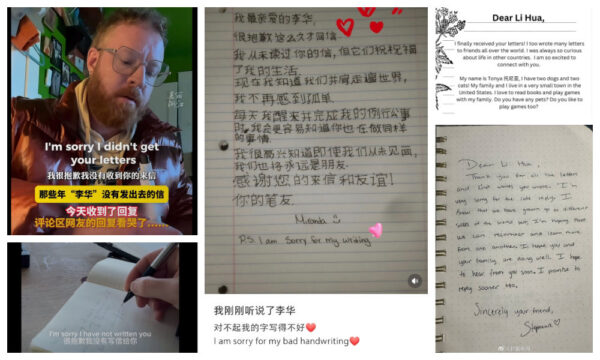

Then, something extraordinary happened: Americans started replying to Li Hua.

One user, Douglas (@neonhotel), posted a heartfelt video of him writing a letter to Li Hua:

📝”Dear Li Hua, I’m sorry I didn’t get your letters. I understand you’ve been writing me for a long time, but now I’m here to reply. Hello, from your American friend. I hope you’re well. Life here is pretty normal—we go to work, hit the gym, eat dinner, watch TV. What about you? Please write back. I’m sorry I didn’t reply before, but I’m here now. Your friend, Douglas.”

Another user, Tess (@TessSaidThat), wrote:

📝”Dear Li Hua, I hope this letter finds you well. I’m so sorry my response is so late. My government never delivered your letters. Instead, they told me you didn’t want to be my friend. Now I know the truth, and I can’t wait to visit. Which city should I visit first? With love, Tess.”

Examples of Dear Li Hua letters.

Other replies echoed similar sentiments:

📝”Dear Li Hua, I’m sorry the world kept us apart.”

📝”I know we don’t speak the same language, but I understand you clearly. Your warmth and genuine kindness transcend every barrier.”

📝”Did you achieve your dreams? Are you still practicing English? We’re older now, but wherever we are, happiness is what matters most.”

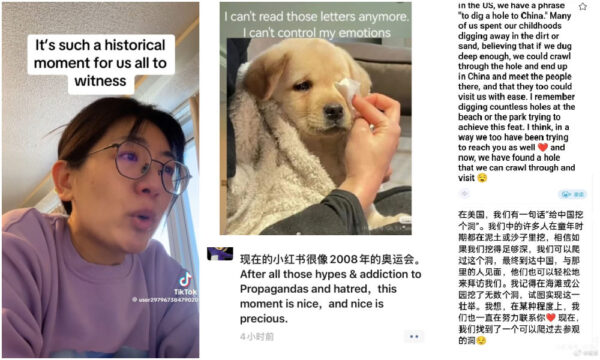

These exchanges left hundreds of users—both Chinese and American, young and old, male and female—teary-eyed. In a way, it’s the emotional weight of the distance—represented by millions of unanswered letters—that resonated deeply with both “TikTok refugees” and “Xiaohongshu natives.”

Emotional responses to the Li Hua letters.

The letters seemed to symbolize the gap that has long separated Chinese and American people, and the replies highlighted the unusual circumstances that brought these two online communities together. This moment of genuine cultural exchange made many realize how anti-Chinese, anti-American sentiments have dominated narratives for years, fostering misunderstandings.

Xiaohongshu commenter.

On the Chinese side, many people expressed how emotional it was to see Li Hua’s letters finally receiving replies. Writing these letters had been a collective experience for generations of Chinese students, creating messages to imaginary foreign friends they never expected to meet.

Receiving a reply wasn’t just about connection; it was about being truly seen at a time when Chinese people often feel underrepresented or mischaracterized in global contexts. Some users even called the replies to the Li Hua letters a “historical moment.”

✳️ Unity in a Time of Digital Divide

Alongside its political and cultural dimensions, the TikTok/Xiaohongshu “honeymoon” also reveals much about China and its digital environment. The fact that TikTok, a product of a Chinese company, has had such a profound impact on the American online landscape—and that American users are now flocking to another Chinese app—showcases the strength of Chinese digital products and the growing “de-westernization” of social media.

Of course, in Chinese official media discourse, this aspect of the story has been positively highlighted. Chinese state media portrays the migration of US TikTok users to Xiaohongshu as a victory for China: not only does it emphasize China’s role as a digital superpower and supposed geopolitical “connector” amidst US-China tensions, but it also serves as a way of mocking US authorities for the “witch hunt” against TikTok, suggesting that their actions have ultimately backfired—a win-win for China.

The Chinese Communist Party’s Publicity Department even made a tongue-in-cheek remark about Xiaohongshu’s sudden popularity among foreign users. The Weibo account of the propaganda app Study Xi, Strong Country, dedicated to promote Party history and Xi Jinping’s work, playfully suggested that if Americans are using a Chinese social media app today, they might be studying Xi Jinping Thought tomorrow, writing: “We warmly invite all friends, foreign and Chinese, new and old, to download the ‘Big Red Book’ app so we can study and make progress together!”

Perhaps the most positive takeaway from the TikTok/Xiaohongshu trend—regardless of how many American users remain on the app now that the TikTok ban has been delayed—is that it demonstrates the power of digital platforms to create new, transnational communities. It’s unfortunate that censorship, a TikTok ban, and the fragmentation of global social media triggered this moment, but it has opened a rare opportunity to build bridges across countries and platforms.

The “Dear Li Hua” letters are not just personal exchanges; they are part of a larger movement where digital tools are reshaping how people form relationships and challenge preconceived notions of others outside geopolitical contexts. Most importantly, it has shown Chinese and American social media users how confined they’ve been to their own bubbles, isolated on their own islands. An AI-powered social media app in the digital era became the unexpected medium for them to share kind words, have a laugh, exchange letters, and see each other for what they truly are: just humans.

As millions of Americans flock back to TikTok today, things will not be the same as before. They now know they have a friend in China called Li Hua.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Insight

Story of Chinese Female MA Graduate Going Missing for 13 Years Sparks Online Storm

The story of the Chinese MA graduate, Ms. Bu, who disappeared in 2011 brings back memories of the Xuzhou mother of eight, who was later revealed to be a victim of human trafficking.

Published

2 months agoon

December 10, 2024

Once a promising Master’s graduate in Engineering, Ms. Bu went missing for 13.5 years. Her return marks the end of her family’s long search, but it is the beginning of an online movement. Chinese netizens are not only demanding answers about how she could have remained missing for so long but also want clarity about the puzzling inconsistencies in her story.

Over the past few days, Chinese social media users have been actively spreading awareness about a case involving a Chinese woman who they suspect became a victim of human trafficking.

Netizens trying to draw attention to this story used the hashtag “Female MA Graduate Becomes a Victim of Human Trafficking” (#女硕士被拐卖#). Between December 6 and December 10, the hashtag garnered 150 million views on Weibo.

The case centers on a Chinese female Master’s graduate from Yuxi District in Shanxi Province’s Jinzhong, who went missing for over thirteen years. Now reunited with her family, netizens are demanding clarity and answers about how she could have disappeared for so long.

This case, which has sparked emotional and outraged responses online, brings back memories of another incident that became a landmark moment for online feminism in China: the case of the Xuzhou mother of eight children, who was discovered chained in a shed next to her family home. Her husband was later sentenced to nine years in prison for his role in her human trafficking.

A Niece’s Search into the Origins of Her Mysterious Aunt

The online movement to raise awareness about this case began well before it gained traction on December 6. It all started when a young woman named Zhang (张) from He Shun County (和顺县) contacted a volunteer group dedicated to reuniting missing individuals. On November 25 of this year, Zhang sought their help in tracking down the family of her somewhat mysterious “aunt.”

According to Zhang, her aunt—who suffered from mental illness—had been living with her uncle for over a decade. Despite this long history, the family knew almost nothing about her past. Wanting to know more, Zhang reached out to the group in hopes of learning about her aunt’s origins.

Zhang claimed that her “aunt” had wandered into their family home one day fifteen years ago. Although they reportedly informed the police, no action was taken, and they allegedly decided to “take her in.” After about two years, she ended up living with Zhang’s uncle, with whom she had two children.

When volunteers visited the family home, they found that the “aunt” was literate and appeared to be well-educated. As reported by the popular WeChat account Xinwenge (December 4 article), the volunteers gradually guided the woman into revealing her name, her family members’ names, and the university she attended.

After passing this information to the police, they confirmed her identity as ‘Ms. Bu’ (卜女士), a missing person from Jinzhong’s Yuxi, about a 2.5-hour drive from He Shun County.

On November 30, Ms. Bu finally returned home, where her 75-year-old father had prepared a welcome banner for her. She was accompanied by her “husband” and their two children, a 12-year-old son and an 8-year-old daughter.

A banner in Jinzhong’s Yuxi: “Welcome home, daughter.”

Although Bu initially did not seem to recognize her father, Chinese media reported that she eventually smiled when he brought out her glasses, which she had worn as a student.

From Doctorate Pursuit to Disappearance

Ms. Bu was born in 1979. As a bright young woman, she graduated high school, attended college, and earned her master’s degree in engineering in 2008. Bu planned to pursue a doctorate afterward. However, due to not renewing her ID card in time, she failed to register for her doctoral exam.

This caused severe stress, and she subsequently developed schizophrenia. Her brother recalled that it was not the first time she had struggled with mental health issues—she had undergone various treatments at multiple hospitals for mental illness between 2008 and 2011.

At the time, Bu reportedly received medical treatment. While recovering at home after being discharged, the then 32-year-old Bu suddenly disappeared in May 2011. Although she was reported as a missing person, her family did not hear from her for over 13 years.

But this is where the questions arise. According to Ms. Zhang, her “aunt” had first walked into their home fifteen years ago, which is impossible since Bu did not go missing until May 2011.

Other aspects of Bu’s disappearance also raise questions. How did she end up in He Shun County? Why did the Zhang family not seek help all these years? And how was she able to have two children with her “husband” despite her fragile mental state?

Authorities Get Involved

While the story of Ms. Bu has received considerable online attention over the past few days, a joint investigation team was set up in Shanxi’s He Shun County to investigate the case. While investigations are still ongoing, new reports suggest that, after her disappearance in May 2011, Bu spent some time wandering alone in multiple nearby villages for over ten days in July and August of that year, exhibiting signs of mental illness.

She was later taken in by Mr. Zhang, a 45-year-old villager, who is now the target of an active criminal investigation. Zhang was aware of Ms. Bu’s mental condition yet engaged in relations with her, resulting in children.

Bu has now been hospitalized for treatment, and authorities are providing support to her children. It is unclear if they will remain with their father—custody arrangements will be determined based on the outcome of the case.

On social media, interest in the case is only growing. On Tuesday, a Xinhua post detailing the latest updates on the case received over 433,000 likes and 44,000 shares shortly after it was posted.

Despite the official updates, questions continue to surround the case of Ms. Bu, nicknamed ‘Hua Hua’ (花花). Given that her mental illness was apparent to so many, why did local authorities fail to intervene earlier? Particularly during the strict social controls and widespread testing of China’s ‘zero-Covid’ era, it is hard to believe that local authorities were unaware of her existence and her mental state. These criticisms and questions are flooding social media and growing louder as more details about her past emerge.

Ms. Zhang, the family niece, further revealed in a livestream that ‘Hua Hua,’ who was reportedly sleeping under a bridge before being taken in by the Zhang family, actually had more than two children. However, as of the time of writing, the fate of these additional children remains unclear.

This case also brings back memories of the Xuzhou mother of eight, another victim of mental illness who was nonetheless “married” to her “husband” and gave birth to eight children. Her story sparked a massive online outcry over how local authorities were complicit in enabling such abuses.

“From the Xuzhou chained woman to the missing Ms. Bu, these women’s tragedies cannot remain incomplete stories,” author Ma Ning (麻宁) wrote on Weibo. “Women are not commodities for marriage and reproduction (…) Let’s continue to follow this case, not just to seek justice for Ms. Bu but also to protect ourselves.”

See more about this story in our follow-up article here.

By Manya Koetse, with contributions by Miranda Barnes

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

What’s on Weibo Chapters

Subscribe

From Weibo to RedNote: The Ultimate Short Guide to China’s Top 10 Social Media Platforms

Collective Grief Over “Big S”

Tuning Into the Year of the Snake

The ‘China-chic Girl’ Image and the Realities of China’s Competitive Food Delivery Market

From “Public Megaphone” to “National Watercooler”: Casper Wichmann on Weibo’s Role in Digital China

Our Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Why Chinese Hit Movie “Her Story” is ‘Good Stuff’: Stirring Controversy and Celebrating Female Perspectives

Chiung Yao’s Suicide Farewell Letter: An English Translation

12-Year-Old Girl from Shandong Gets Infected with HPV: Viral Case Exposes Failures in Protecting Minors

Breaking the Taboo: China’s Sanitary Pad Controversy Sparks Demand for Change

Weibo Watch: Christmas in China Is Everywhere and Nowhere

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

Weibo Watch: China’s Online Feminism Is Everywhere

Story of Chinese Female MA Graduate Going Missing for 13 Years Sparks Online Storm

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight10 months ago

China Insight10 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music11 months ago

China Music11 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Insight12 months ago

China Insight12 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Digital9 months ago

China Digital9 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

Roger Guindon

January 22, 2016 at 5:14 pm

Being a foreigner in another country I certainly would not want a country to change ay any cost, a symbol that has thousands of years of history.. History is history that’s why we travel to educate ourselves on other cultures. :O)

Charuko Nakamachi

January 23, 2016 at 8:05 pm

I find this article to be interesting. So much angst over a symbol used for thousands of years with benevolent intent, usurped by one malevolent group a mere ninety four years ago, and troubled over today.

I find myself both torn and mystified by this symbol. It seems harsh to me in it’s appearance with it’s sharp angles, but the Buddhist usage is one of benevolence. My sense is that the NAZI usurpation of this symbol has taken it out of its context, and stolen it from kinder hearts.

Beyond that, it’s a very Japanese decision to remove it from maps that visitors would be using. The idea is to promote harmony and to make visitors as comfortable as possible. I believe that’s an exceptionally benevolent and laudable thing to do.

Domonique Brown

May 28, 2019 at 4:51 pm

That’s ignorant. Stop defending white supremacy. You should check your privilege. You probably think the “okay” hand gesture is safe to use. #BLM

Peter Herz

August 17, 2016 at 6:26 pm

I am an American who is 1/2 Central European Jewish. My father, God rest him, knew of family who perished in the Shoah. But it did not take me long to recognize the wanzi as a symbol of Buddhism, not Naziism, when I lived in Taiwan. I would tell Japan to keep the wanzi, or however the Japanese pronounce it, to mark temples on their maps, and I would tell the rest of the world to learn some history other than that of Europe over the past three centuries.

Andy Tithesis

August 27, 2018 at 4:37 pm

Most westerners have a Pavlovian response to anything relatable to the Nazi regime. We in America are taught very little of history outside a handful of our own believed victories. Few pay attention to even that I am afraid. As with most humans if you give them a cultural green light to despise and condemn something they will do so without a thought. Nobody wants to learn the details when they can act aggressively and spew venom as it is much more fun for most. Mankind will always have is beast not far from his heart but separated almost completely from his brain. I consider myself a Buddhist even though I am said to be tainted by my upbringing in western culture. I actually agree with that. Eastern thought is a rare thing these days worldwide. If you are on the computer reading this you to are more than likely tainted by the western influence. Still though there is redemption for those who can take it all in and turn something new and benevolent outwards. This symbol should never be taken down if put up for non radical reasons related to ignorance and racism. You should not be upset with the foreshadowed foreigners you should be upset with your own powers bowing to the almighty currency they greedily see coming. Your map company is a traitor to it’s own roots and you should let them know how you feel. Shall everything be made for sale to outside influence? It seems the way of the world as of late and it is sad and depressing. I have every religion in my heart and consider myself a student to them all if they will teach me wisdom beyond what our current world has to offer. Which really sets the bar pretty low actually but I shall remain hopeful that we as a species and a single race, the human race, can rise above the capitalist swindle and put a stop to such moronic and shameful sell out tactics such as this. This bewilders me and there should really be more articles like these on our side of the pond but sadly there is not. This is my opinion anyways. I thank you for your time. All are my brothers and sisters. Good luck to you all always. ♥

jamey james

January 6, 2019 at 9:32 pm

I am in agreement that one should respect traditional history. I have watched a lot of showlin stuff and had worked the fact out for myself of the difference between the two symbols being clockwise and anticlockwise. This also includes the colours gold and or black. I think that one should educate them self and learn the proper history before condemnation application.

Laura

January 25, 2019 at 6:10 pm

You MUST keep your traditions and wanzi. Don’t let the Occident tell you what you have to do. If the foreigners don’t like that, they can go back home ! Both Swastika have NOTHING to do with Nazism. We must stop this propaganda and protect the culture all over the world.

In Europe it becomes also very difficult. For example in Latvia, where the swastika is a very old worshiped symbol.

A french friend

Rancid Boar

July 9, 2020 at 7:58 am

This article doesn’t do a great job representing the Swastika.. The Swastika is clockwise and Suawstika is counterclockwise. Both were used since ancient times… The first person to use the Sanskrit word swastika and describe it was the Sage Panini. Su=Good Astik=To be, therefore the swastika means to be good… Nazis didn’t design thiers since they just bastardized the design and meaning. Still it isn’t an anti-Semitic, ignore that aspect. Your selective attention and cognitive dissonance has already let you ignore the Christian Cross and Sword of Islam as anti-Semitic symbols, despite the fact that those were actually used to crucify and kill Jews. Only Western mf with identity crisis can make a auspicious symbol a hate symbol, and a torture device a ‘holy’ cross… Makes perfect sense… The Swastika is eternal and will be used as long as humanity exists.

salesh Prasad Mishra

October 9, 2021 at 7:02 am

Oh wonderful This again.. You know folks, if you happen to one day read media not made by the west, or controlled by the west? Maybe you will open your eyes one day.

and for the rest of you you should stop actually swallowing whole would Western media is shoving down your throat.

it must also concern you that there are religions and even Nations that are older than your Bible but of course that doesn’t matter to you does it I know it’s a shocker.

even everything that you read on Wikipedia has a very Western vibe to it and by that you know exactly what I mean they’re always talking about our lease to them. You have to start learning how other people and other cultures actually work once you do you realize exactly what kind of mind virus has been implanted in your brain.

think freely